Social housing tenants

Key findings

- As at 30 June 2015, there were around 817,300 tenants in social housing, with the majority (82%) of these in public rental housing.

- The number of households living in community housing has almost doubled (up 84%) between 2008–09 and 2014–15.

- Large proportions of social housing tenants are either older persons aged 55 years or over (32% for public rental housing and 27% for community housing) or children aged under 14 years (39% for SOMIH).

- Across all social housing programs, main tenants were more likely to be women (62%).

- Social housing tenants were less likely than the general population to have achieved post year 12 or equivalent qualifications (between 2 and 9% across housing sectors compared to 17% of the general population).

- Between half (51% CH) and three-quarters (74% SOMIH) of all social housing tenants were not in the labour force.

- 4 in 10 public rental housing tenants had been in their tenancies for over 10 years.

Social housing includes all rental housing owned and managed by government or non-government organisations (including not-for-profit organisations) which can be let to eligible households. Social housing rents are generally set below market levels and are based on the income of the household.

Over recent years, social housing has increasingly been allocated to households with complex needs, such as those with disability and on very low incomes. As at 30 June 2015, there were almost 394,200 households in social housing, with the majority in public rental housing (315,000), 9,700 in state managed and owned Indigenous housing (SOMIH) and 69,500 in mainstream community housing.

There were 17,500 Indigenous Community Housing (ICH) dwellings as at 30 June 2015 (household estimates are not available from that data collection).

Number of tenants in social housing

As at 30 June 2015, there were an estimated 817,300 tenants in social housing (excluding Queensland and the Northern Territory, for which tenant characteristics were not available). Of these tenants, 82% or around 667,000 were in public housing; 4% or around 32,100 were in SOMIH; and, 14% or around 118,200 were in community housing.

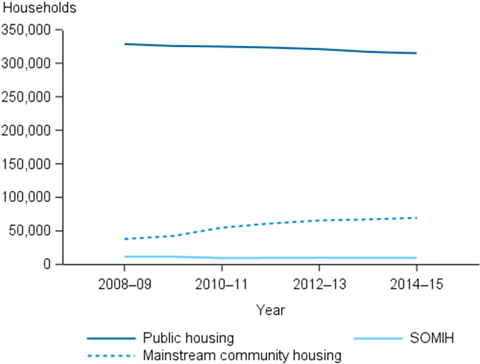

The number of public rental housing households has decreased between 2008–09 and 2014–15. Over this period, the number of public rental households fell from 328,700 to 315,000 (a fall of 4%).

SOMIH household numbers have also fallen during this time, from 11,600 to 9,700 (a fall of 20%).

In contrast, over the same time period, the number of mainstream community housing households has almost doubled. Between 2008–09 and 2014–15, the number of community housing households increased from 37,800 to 69,500 (a rise of 84%), with an increase of 4% in the last 12 months.

These changes reflect a gradual but steady shift of policy focus towards growing the community housing sector and transferring ownership or management of public rental housing stock to community housing organisations. The decrease in the number of public rental households was offset by an increase in mainstream community housing households. This shift in the distribution of housing stock reflects strategies to grow the community sector, as mainstream community housing can potentially provide more flexible and innovative affordable housing options.

Figure SHT.1: Number of social housing households, 2008–09 to 2014–15

Source: AIHW National Housing Assistance Data Repository, 2014–15. Source data.

Tenant demographics

Public rental housing tenants

Of public housing households, 62% of main tenants were female, and 53% were comprised of single adults living alone. Forty-four per cent reported a disability, although only 30% identified a disability support pension as their main source of income. A further quarter (25%) of tenants indicated an age pension as the main source of income.

A typical public housing tenant can be described as an older female (55+) living alone.

SOMIH tenants

Of SOMIH households, three-quarters of main tenants were female (76%) and two-thirds (65%) were aged 25–54 years. In terms of household composition, sole parents with dependent children were the largest family type (37%), followed by single adults (25%). Thirty-six per cent (36%) of SOMIH tenants reported having a disability.

A typical SOMIH tenant can be described as a single female of working age (25–54) with dependent children.

Mainstream community housing tenants

Of mainstream community housing households, almost 6 in 10 (59%) were female, and just over 6 in 10 (63%) were aged 45 years and over. Single adults represented the highest proportion of household compositions (58%), followed by group and mixed households (17%). More than one-third (36%) of mainstream community housing tenants reported having a disability.

A typical community housing tenant can be described as an older female (45+) living alone.

Educational attainment

The 2014 National Social Housing Survey (NSHS) found that almost half (49%) of public housing tenants, almost two-thirds (61%) of SOMIH tenants, and less than half (43%) of community housing tenants of all ages reported that their highest level of educational attainment was Year 10 or equivalent. Across all social housing programs, around 2% of respondents reported that they had not completed any formal education (AIHW 2015).

Comparing the highest level of educational attainment for respondents in the 2014 NSHS to estimates for the general population aged 15–74 years illustrates some differences between the two groups. The proportion for whom Year 12 or equivalent was the highest level of education completed was similar for both the 2014 NSHS sample (20% for PH, 21% for SOMIH and 18% for CH) and for the general population aged 15-74 years (18%). However, social housing tenants were less likely to have achieved post year 12 or equivalent qualifications than the general population aged 15-74 years, for example:

- Those in the general population aged 15–74 years were more likely to have achieved a highest level of education of Bachelor degree or above (17%) than community housing tenants (9%), public housing tenants (5%) or SOMIH tenants (2%).

- The proportion attaining post-secondary school qualifications (that is, certificate, diploma, advanced diploma or bachelor degree or above) in the general population aged 15–74 years (44%) was higher than that for community housing (30%), public housing (22%) and SOMIH tenants (12%).

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 6227.0 Education and Work, Australia, May 2015

Age profile

In general, large proportions of social housing tenants are either older persons aged 55 years or over and children aged under 14, although the proportions in these groups vary across the different social housing programs.

As at 30 June 2015, a relatively high proportion of tenants living in public rental housing, SOMIH and mainstream community housing households were children. Almost a quarter (23%) of public rental housing, 39% of SOMIH and 20% of mainstream community housing tenants were aged 0–14 years old.

For older age groups, 32% of public rental housing, 13% of SOMIH and 27% of mainstream community housing tenants were aged 55 years and over.

The tenant age profile across social housing programs differ greatly. Where almost one-third (32%) of public rental housing tenants and more than one-quarter (27%) of mainstream community housing tenants were aged 55 years and over, over one-third (39%) of SOMIH tenants were aged 0–14 years.

Figure SHT.2: Age and sex distribution of all tenants in public rental housing, SOMIH and mainstream community housing dwellings, 2015

Source: AIHW National Housing Assistance Data Repository, 2014–15. Source data.

Employment

The 2014 National Social Housing Survey found that between half and three-quarters of all social housing tenants were not in the labour force—that is, they were neither working nor currently looking for work. Conversely, around 28% of public rental housing, 30% of mainstream community housing and 37% of SOMIH tenants were in the workforce.

Reflecting the different age profile across the social housing programs, those in SOMIH households were less likely to be retired (16%) when compared to tenants in public rental (38%) or community housing (37%).

The remainder of those in social housing were either studying, volunteering, were a full-time parent or carer, were retired or unable to work due to long-term illness or injury.

The 2014 National Social Housing Survey included questions aimed at investigating barriers or disincentives for social housing tenants to either enter the workforce or increase the number of hours worked per week. Tenants working part-time, unemployed or not in the labour force were asked to identify the influences on their current employment status. The 3 strongest influences on employment status were the need for more training, education or work experience; the desire/need to stay home and look after children; and financial concerns (AIHW 2015).

In addition, the provision of social housing may affect the work decisions for recipients quite differently. There are many perceived employment disincentives for social housing tenants. These may include—rent increases as a result of increased income; social housing ineligibility where their income exceeds a certain threshold; as well as a potential lack of social housing availability in areas with increased employment prospects. Alternatively, social housing may afford tenants with greater stability, increasing their opportunities to find and maintain employment (Productivity Commission 2015).

Tenants’ length of tenure

A substantial proportion of households in public rental housing and SOMIH remain in tenure for long periods of time. As at 30 June 2015, 42% of public rental housing and 32% of SOMIH households had been in the same tenancy for over a decade. Most tenancies had been in place for over 5 years for public rental housing households (64%) and SOMIH households (55%). It is worth noting however that around one in five tenancies remain in place for less than a year (18% for PH and 23% for SOMIH). Comparable data are not currently available for mainstream community housing.

| Tenure length | Public Housing Number |

Public Housing Per cent |

SOMIH Number |

SOMIH Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months or less | 15,029 | 4.8 | 610 | 6.3 |

| 6 months to 1 year | 40,796 | 13.0 | 1,641 | 16.9 |

| 2 to 4 years | 59,015 | 18.7 | 2,108 | 21.7 |

| 5 to 9 years | 68,329 | 21.7 | 2,225 | 22.9 |

| 10 to 19 years | 86,040 | 27.3 | 2,177 | 22.4 |

| 20 to 29 years | 34,813 | 11.1 | 703 | 7.2 |

| 30 or more years | 10,941 | 3.5 | 268 | 2.8 |

Note:

- Records with missing start date have been excluded.

- Data are for ongoing households; therefore tenure length has been calculated using the tenancy start date and an end date of the 30th June of the financial year.

- Data on mainstream community housing tenure length were not available.

Source: AIHW National Housing Assistance Data Repository, 2014–15.

Nationally, 2% of public rental housing tenants and 3% of SOMIH tenants transferred to a different dwelling during 2014–15. This may be due to state housing authorities seeking to match tenant characteristics to household size. For example, by moving a single tenant household into a smaller dwelling to make room for a larger family household, or tenants requesting relocation to a different geographic area. Households leaving social housing (as measured by exit rates) were slightly higher in 2014–15 than transfer rates, with 7% of public rental tenants and 9% of SOMIH tenants ending their tenancies during the year.

Tenant satisfaction

'Tenant satisfaction' is defined as the proportion of tenants in social housing who said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their housing service provider. As at 30 June 2014, tenants in community housing were consistently more satisfied with their housing provider (80%) compared with other social housing providers (73% for public rental housing and 58% for SOMIH) (AIHW 2015).

Satisfaction with the location of their dwelling in terms of proximity to various services and facilities is high across all social housing programs. In particular, proximity to emergency services, medical services and hospitals was consistently rated highest in terms of importance and social housing tenants consistently rated the location of their dwelling as meeting the needs of their household. This is a positive finding given that health and medical services as well as mental health services were the most frequently used services by social housing tenants in the twelve months prior to the survey.

Social and economic benefits from living in social housing

Affordable, safe and secure housing can contribute to a range of health and wellbeing outcomes and contribute to people's ability to engage economically and socially in their community.

Tenants who reported social and economic participation benefits from living in social housing varied across their individual circumstances and housing programs. Across all social housing programs, 94% of tenants reported they felt 'more settled' and 82% felt 'part of the community'. In terms of employment and education, 67% of social housing tenants felt they were more able to improve their job situation and 74% felt more able to start or continue education/training due to being supported in social housing. Also, 85% reported having better access to services and 94% were better able to manage their rent/money. Of all social housing tenants, only 25% reported no social or economic benefit at all from living in social housing (AIHW 2015).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 6227.0 Education and Work, Australia, May 2015.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2015. National Social Housing Survey: detailed results 2014. Cat. No. HOU 278. Canberra: AIHW.

- Productivity Commission 2015. Housing Assistance and Employment in Australia. Commission Research Paper, Canberra.