Children with mental illness

Key findings

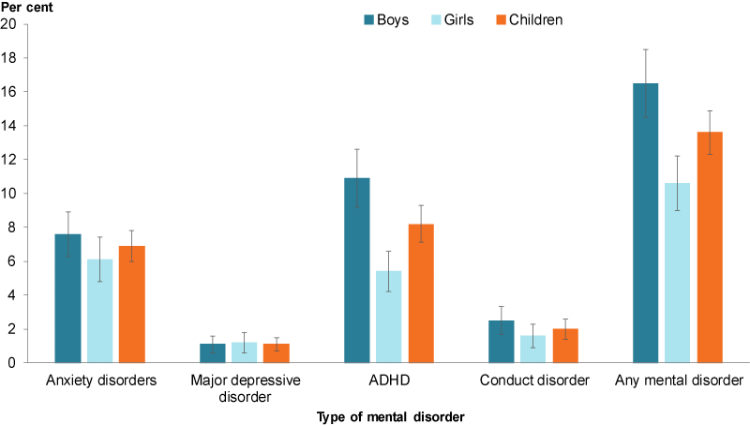

- In 2013–14, an estimated 314,000 children aged 4–11 (almost 14%) experienced a mental disorder. Boys were more commonly affected than girls (17% compared with 11%).

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the most common disorder for children (8.2%). It was also the most common disorder among boys (11%).

- Anxiety disorders were the second most common disorders among all children (6.9%), and the most common among girls (6.1%).

Mental health is a state of wellbeing in which an individual realises their own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and make a contribution to their community. Poor mental health can impact on the potential of young people to live fulfilling and productive lives (WHO 2014a). See ‘Social and emotional wellbeing’.

Mental illness (also referred to as mental health disorders) are diagnosable health conditions and most can be successfully treated. They comprise a broad range of problems but are generally characterised by some combination of abnormal thoughts, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others. Examples are:

- schizophrenia

- depression

- disorders due to drug abuse.

Mental illness can vary in severity and duration. It may also be episodic (AIHW 2018).

Mental illness affects individuals, families and carers. It also has far-reaching influence on society, through issues such as poverty, unemployment and homelessness (AIHW 2018).

Mental health and many common mental illnesses are influenced by social, economic, and physical environments factors. For children, loving, responsive and stable relationships with a caring adult help build secure attachment between child and caregiver. This is essential for healthy social and emotional development. Secure attachment to the primary caregiver in the early years helps to protect against anxiety and boosts the ability to cope with stressors (WHO 2014b).

Mental health problems in childhood can have a substantial impact on wellbeing. In addition, there is strong evidence that mental disorders in childhood and adolescence predict mental illness in adulthood (WHO 2014b; Lahey 2015; NMHC 2019a).

At the same time, childhood presents the greatest opportunity for intervention. Investing in prevention and early intervention gives children the best opportunity for good mental health and wellbeing (NMHC 2019a). For high risk groups, such as children affected by violence, abuse, maltreatment or poverty, early intervention can help reduce disparities between the mental health of these children and children in psychologically healthy environments (NMHC 2019a).

To ensure that mental illnesses are diagnosed and treated early to prevent lifelong disability, a National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy is being developed. The strategy aims to provide a framework for preventing mental illness and reducing its impact on children, families and the community (NMHC 2019b).

A wide variety of support services are available to assist children with emotional and behavioural problems. These include:

- health services

- school services

- telephone counselling services

- online services (Lawrence et al. 2015).

The Be You program provides educators with knowledge, resources and strategies for helping children and young people achieve their best possible mental health (Be You 2019).

In 2015, for children aged 5–14, 3 of the 5 leading causes of the total burden of disease were mental disorders:

- anxiety disorders ranked second

- depressive disorders third

- conduct disorders fourth (AIHW Burden of Disease database).

For boys and girls aged 5–14, anxiety disorders were the second leading cause of total burden. Conduct disorders were the third leading cause of total burden for boys while depressive disorders were the third leading cause for girls (AIHW 2019).

Box 1: Data sources on mental illness

Data on mental illness are sourced from the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (also known as the Young Minds Matter Survey), and the Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool. This household survey was conducted in 2013–14 by the Telethon Kids Institute at the University of Western Australia in partnership with Roy Morgan Research. Children aged 4–11 are reported in this section based on parent and/or carer reported data.

Children with mental health disorders are children who meet the criteria for a medical diagnosis of a mental disorder within the 12 months before the survey. Diagnoses were based on the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition). The DSM-IV includes all currently recognised mental health disorders.

How many children have mental illness?

In 2013–14, an estimated 314,000 children aged 4–11 (almost 14%) experienced a mental disorder in the 12 months before the survey (Lawrence et al. 2015). Boys were more commonly affected than girls (17% compared with 11%).

ADHD was the most common disorder for children (8.2%), and the most common among boys (11%).

Anxiety disorders were the second most common disorders among all children (6.9%), and the most common among girls (6.1%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mental illness among children aged 4–11, by gender, 2013–14

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW analysis of the Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool.

Overall almost:

- 3 in 4 (72%) had mild disorders

- 1 in 5 (20%) had moderate disorders

- less than 1 in 10 (8.2%) had severe disorders

- Severe disorders were more common among boys (9.9%) than girls (5.6%).

Children with mental illness use a range of services (Box 2).

Box 2: How many children use services?

A wide variety of services are available to support children with emotional and behavioural problems. The 2013–14 Young Minds Matter survey collected information on 4 key types of services:

- health services

- school services

- telephone counselling service

- online services.

For children aged 4–11, very few were reported to have used telephone or online services. However, parents and carers often reported not knowing which services children had used (Lawrence et al. 2015).

Data from the survey indicated that in the previous 12 months:

- Around 49% of children with mental disorders had used services for emotional or behavioural issues (50% boys and 48% girls).

- Service use was highest among children with a major depressive order (73%) followed by children with conduct disorders (66%), children with anxiety disorders (54%) and children with ADHD (49%).

- Service use varied with severity of mental disorder—40% of children with mild disorder, 68% with moderate disorders and 83% with severe disorders.

- The 3 most common types of health service providers were general practitioner (30%), paediatrician (23%) and psychologist (20%).

- The 3 most common types of school services were individual counselling (20%), special class or school (13%) and group counselling or support program (6.5%).

Survey data suggests service use by children with mental disorders in Australia increased significantly between 1998 and 2013–14 (Lawrence et al. 2015).

For more information of mental health service use in Australia, see Mental health services in Australia.

How does mental illness relate to family type and family functioning?

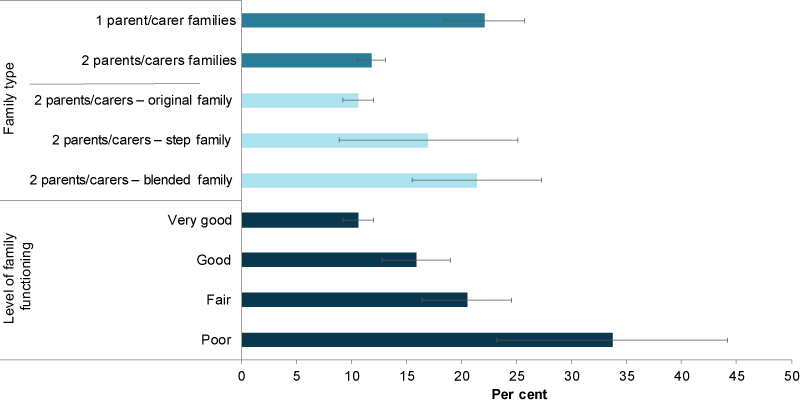

In 2013–14, children living:

- in families with 2 parents or carers were less likely to have mental health disorders than children living in families with 1 parent or carer (12% compared with 22%) (Figure 2)

- with their original families (with 2 parents or carers) were less likely to have mental health disorders than children living with blended families (11% compared with 21%).

Mental disorders were also more common among children living in families with poor family functioning (34%) compared with those in families with very good family functioning (11%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mental illness among children aged 4–11, by family type and functioning

Note: Stepfamilies have at least 1 resident stepchild, but no child who is the natural or adopted child of both partners. Blended families have 2 or more children where at least 1 is the natural or adopted child of both parents, and at least 1 is the stepchild of 1 of them.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW analysis of the Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool.

How does mental illness impact on schooling?

Of all children aged 4–11 with a mental disorder, children with a major depressive order on average missed the most days of school due to their symptoms (14 days in the previous 12 months). This was more than twice as high as for children with anxiety disorders (6 days) and more than 3 times as high as for children with ADHD (4 days) (Lawrence et al. 2015).

While separation anxiety had the highest prevalence among children, generalised anxiety disorder was on average associated with more days off school (10 days compared with 6 for separation anxiety) (Lawrence et al. 2015).

The level of impact on functioning at school varied with the type of mental disorder. The greatest impact was due to symptoms of major depressive disorder. This disorder had a severe impact on school function for close to half (45%) of students with this disorder. The symptoms of ADHD and anxiety disorders had a mild impact on schooling for 42% and 37% of students respectively. Almost half (46%) of those with conduct disorder and 27% with anxiety disorders experienced no impact on schooling according to parents and carers (Lawrence et al. 2015).

Average NAPLAN test scores were lower for students with mental disorders, compared to those with no mental disorder (Goodsell et al. 2017).

Has mental illness prevalence changed over time?

Between 1998 and 2013–14, the prevalence of major depressive disorder among children aged 6–11 remained the same (1.4%), while the prevalence of conduct disorder and ADHD decreased (3.2% to 2.2% and 13% to 9.2%, respectively). The proportion of those aged 6–17 who had any of these disorders decreased slightly from 12% to 11%.

Is it the same for everyone?

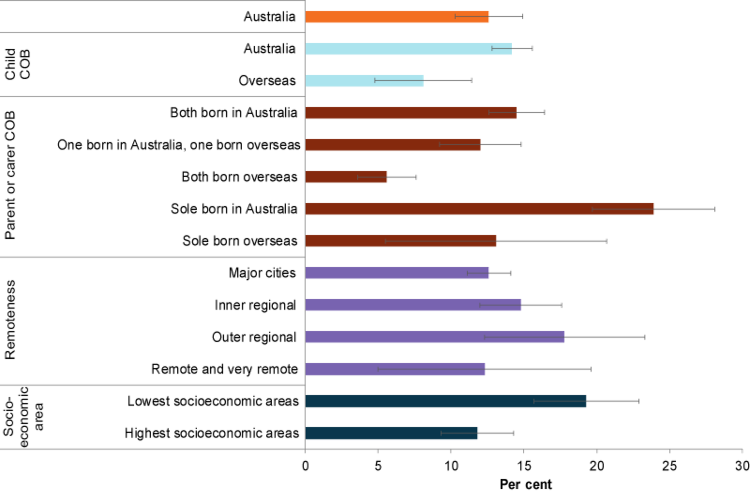

Mental illness was more common among children born in Australia (14%) compared with children born overseas (8.1%) (Figure 3). It was also more common among children with both carers born in Australia (15%) compared with both carers born overseas (5.6%).

Other studies involving young immigrants have also found fewer mental health problems reported by immigrant adolescents compared with non-immigrant adolescents (Minas et al. 2013). However, some studies on the prevalence of mental illness of the children of immigrants have found similar rates between children of immigrants and those of Australian-born parents (Minas et al. 2013).

Mental illness was also more common among children living in areas with the lowest socioeconomic areas (19%) compared with those living in the highest (12%) (Figure 3).

Children in households where parents had lower levels of education, lower household income, or were living in public housing also had higher proportions of mental disorders. However, there may be overlapping issues here, for example some children living in households with lower incomes may also live in public housing (AIHW analysis of the Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool).

Figure 3: Mental illness among children aged 4–11, by selected population groups, 2013–14

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW analysis of the Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool.

Data limitations and development opportunities

While there are no plans to repeat the Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, the Intergenerational Health and Mental Health Study announced in Australia’s Long Term National Health Plan will provide a detailed information base for mental health planning at local level over the next decade (Department of Health 2019).

Where do I find more information?

For information on topics related to mental health in Australia’s children, see:

- Social and emotional wellbeing (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire results and mental health competence)

- Injuries (information on suicide and self-harm)

- Bullying.

For more information on:

- mental disorders of young people aged 12–17, see: AIHW’s National Youth Information Framework.

- mental health disorders, see: The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing and The Young Minds Matter Survey Results Query Tool

- mental health care services and support, including presentations to emergency departments, hospitalisations and mental health-related prescriptions, see: Mental health services in Australia.

AIHW 2018. Mental health services—in brief 2018. Cat. no. HSE 211. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2019. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015. Australian Burden of Disease series no. 19. Cat. no. BOD 22. Canberra: AIHW.

Be You 2019: Growing a mentally healthy generation. Viewed 23 September 2019.

Goodsell B, Lawrence D, Ainley J, Sawyer M, Zubrick SR & Maratos J 2017. Child and adolescent mental health and educational outcomes. An analysis of educational outcomes from Young Minds Matter: the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Perth: University of Western Australia. Viewed 17 May 2019.

Lahey B 2015. Editorial: why are children who exhibit psychopathology at high risk for psychopathology and dysfunction in adulthood? JAMA Psychiatry 72(9):865–866.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven De Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J et al. 2015. The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 17 May 2019.

Minas H, Kakuma R, San Too L, Vayani H, Orapeleng S, Prasad-Ildes R et al. 2013. Mental health research and evaluation in multicultural Australia: developing a culture of inclusion. Prepared by MHiMA for the National Mental Health Commission. Viewed 26 September 2019.

NMHC (National Mental Health Commission) 2019a. Monitoring mental health and suicide prevention reform: national report 2019. Sydney: NMHC.

NMHC 2019b. National Children’s mental health and wellbeing strategy. Viewed 23 September 2019.

WHO (World Health Organization) 2014a. Mental health: a state of well-being. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 8 May 2019.

WHO 2014b. Social determinants of mental health. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 29 September 2019.

Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, 2015

- Original families contain at least one child who is the natural, adopted or foster child of both partners in the couple and no step children. The Australian Bureau of Statistics refers to this category as ‘intact families’.

- Step-families have at least one resident stepchild, but no child who is the natural or adopted child of both partners.

- Blended families have two or more children; at least one child who is the natural or adopted child of both parents, and at least one who is the step child of one of them.

- Other families have no children who are the natural, adopted, foster or step child of either parent or carer. These include families with children being raised by their grandparents or other relatives.

- The survey cannot produce estimates of mental disorders and service use for Indigenous peoples. Random sampling alone with the number of participants for this survey was not considered sufficient for generation of these data within acceptable confidence intervals. A separate Indigenous sample was not included as there are important cultural issues in appropriately measuring mental health and wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children that could not be addressed within the framework of the population survey. A separate study would need to be undertaken to assess the mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people in a culturally appropriate manner (Lawrence et al. 2015).

For more information, see Methods.

If you or someone you know needs help please call:

Lifeline 13 11 14

beyondblue 1300 22 4636

Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800