Chapter 6 Preventing and treating ill health

6.0 Introduction

A fundamental aim of any health system is to prevent disease so that people remain as healthy as possible for as long as possible. Should they become ill, people need to have access to timely and appropriate treatment. This chapter examines these two functions of the health system: prevention and treatment.

Health prevention and promotion strategies—such as sanitation, immunisation, anti-smoking campaigns, clean air and water, food safety and workplace health and safety—have helped to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and to create safer, healthier environments in which to live.

Immunisation is one of the most effective health-prevention strategies, and in Australia more than 90% of children are fully immunised by the time they start school.

Population-based cancer screening is another major area of prevention activity in Australia, with national programs for breast, cervical and bowel cancers. In each of the 2-year periods 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, more than 3.8 million women took part in the National Cervical Screening Program. Although this program reached almost 60% of the eligible population, there is room for improvement.

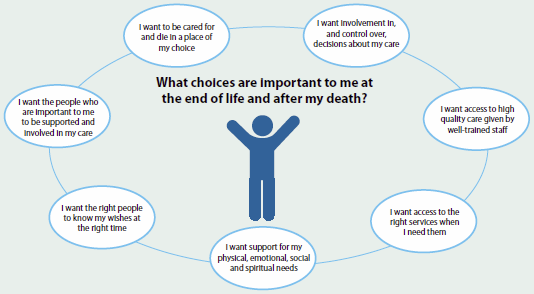

As outlined in Chapter 2, Australia's health system is a complex network of providers, services and settings, not all of which are covered in Australia's health 2016. This chapter focuses principally on primary health care and hospital services, and on selected specialised treatment services: mental health services and alcohol and other drug treatment services. This chapter also includes feature articles on end-of-life care and on Indigenous women's access to maternal health services.

Primary health care is generally the first point of contact that people have with the health system, and it is also the gateway for access to other, specialised health services. In 2014–15, more than one-third of the 335 million out-of-hospital Medicare services claimed were for non-referred consultations with general practitioners who, along with allied health professionals, play a major role in primary care.

Despite the importance of the primary health care sector, only limited data are available on the delivery of primary health care in Australia. (An exception is the Indigenous primary health care sector, where regular and comprehensive performance data are collected, and this is profiled in 'Chapter 6.5 Using data to improve the quality of Indigenous health care'.)

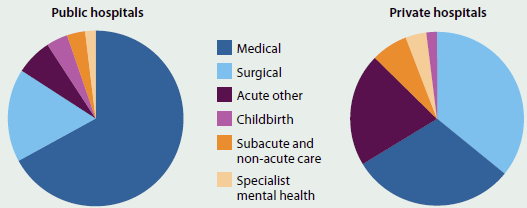

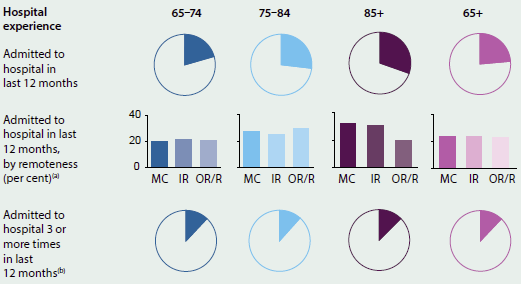

This chapter also includes an overview of Australia's public and private hospitals, which provide nearly 90,000 hospital beds and about 28 million days of patient care each year. It examines safety and quality in hospitals, how hospital care is changing, and health care use by older Australians, who account for an increasing share of our population and hospital patients.

6.1 Prevention and health promotion

A fundamental aim of any health system is to prevent disease and reduce ill health so that people remain as healthy as possible for as long as possible. Reducing the impacts of preventable illness, disability and injury increases participation rates in the labour force and education and increases the quality of life enjoyed by individuals and society (Gruszin et al. 2012). In Australia, health prevention activities have long played a part in improving the health of Australians—for example, early prevention measures in the 1800s included sewerage systems and water supply in Sydney to improve public sanitation (Hector 2011). Some prevention activities target all people in a given population (for example, fluoridated water), while others target particular groups based on age or other risk factors (for example, breast cancer screening).

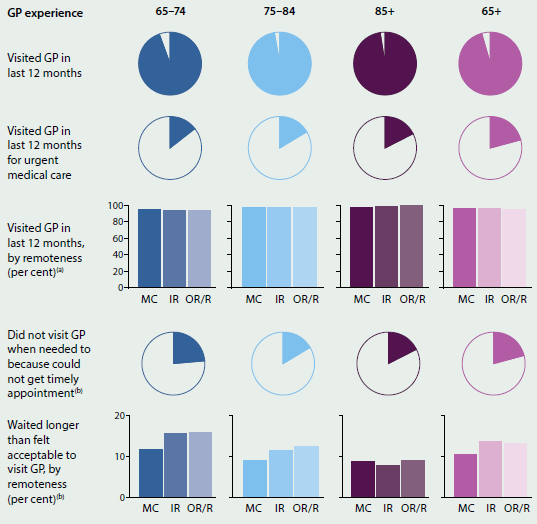

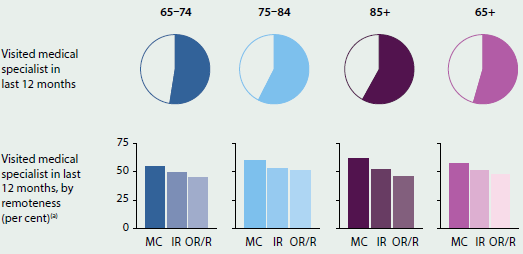

Health promotion (for example, education, social marketing, legislation and regulation) is an important part of disease prevention and can be used to help build social and physical environments that support healthy behaviours. In the past, prevention and promotion strategies, such as sanitation, immunisation, quarantine, workplace health and safety, safe birthing practices, and better food and water supply, have helped to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, improve maternal and child health, and create safer, healthier environments in which to live and work. These strategies continue to be vital today.

In 2013–14, $2.2 billion, or 1.4% of total health expenditure, went to public health activities, which included prevention and health promotion (AIHW 2016). This did not include spending in non-health sectors such as road safety, the environment, and schools. The proportion of health expenditure allocated to public health has been declining since it peaked in 2007–08 (2.2%) (AIHW 2016).

This snapshot highlights selected prevention and promotion activities.

Immunisation and vaccination

Immunisation is an important public health intervention to stop the spread of diseases that can cause serious illness and death. Worldwide, immunisation programs prevent an estimated 3 million deaths every year (Department of Health 2015a).

In Australia, immunisation begins at birth and vaccinations for children cover 13 diseases, including measles, mumps, diphtheria and whooping cough (Department of Health 2015a).

For immunisation to provide the greatest benefit, a large proportion of the community must be fully immunised. In the past, target coverage rates have been around 90%, with these rates for children being largely achieved (Table 6.1.1). However, due to a higher level of vaccine coverage required to achieve community immunity for measles, a recent national aspirational immunisation target (that is, the proportion of people who are fully immunised) has been set at 95% (Department of Health 2016c).

| Group | Age (years)(a) 1 |

Age (years)(a) 2 |

Age (years)(a) 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

All children All children |

92.3% | 89.3% | 92.6% |

Indigenous children Indigenous children |

88.7% | 86.2% | 93.9% |

- Children aged 1, 2 and 5 refer to 12–<15 months, 24–<27 months and 60–<63 months, respectively.

Sources: Department of Health 2016a, 2016b.

A national Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program (using the quadrivalent HPV vaccine which protects against four types of HPV) was introduced for females in 2007 and extended to males in 2013. Australia was the first country to introduce such a program and there has been a fall in HPV-related infection in females, high-grade cervical abnormalities (for example, precancerous lesions of the cervix) in young women, and genital warts among females and males since it began (Department of Health 2015b; NCIRS 2014). For example, 4 years after the beginning of the program, there was a substantial decrease in vaccine-targeted HPV genotypes (the specific types of HPV covered by the vaccine) among women aged 18–24—from 29% in 2004–2007 to 6.7% in 2010–2011 (Tabrizi et al. 2012). Of children turning 15 in 2014, 73% of girls were fully immunised (having received three HPV vaccinations) and 60% of boys were fully immunised (NHPVVPR 2015).

The Australian Government also funds a range of vaccinations for eligible people under the Immunise Australia Program. For example, the flu vaccine is available, for free, to pregnant women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, people aged 65 and over, and people who are medically at risk and thus more likely to experience complications from flu (Department of Health 2015a).

Success stories

Two of the biggest prevention success stories in Australia have been reductions in road deaths and tobacco smoking rates. Even though the number of registered vehicles continues to increase over time, road deaths have fallen—from nearly 3,800 in 1970 to fewer than 1,200 in 2014 (BITRE 2010, 2015). During that time, a number of national road safety initiatives were introduced, including the compulsory wearing of seat belts, random breath testing and 50 km/h residential street speed limits.

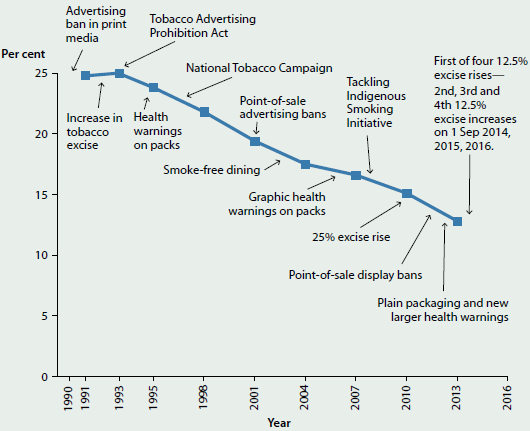

Similarly, comprehensive public health policy approaches, including promotion, regulation and increased taxation on tobacco products, have contributed to the steady reduction in the daily tobacco smoking rate from 24% in 1991 to 13% in 2013 for people aged 14 and over (Figure 6.1.1). This reduction has been particularly marked for younger people, with the fall in daily smoking rates over the past decade occurring predominantly among people aged 18–49. The average age at which young people aged 14–24 smoked their first cigarette has risen steadily since 2001 (15.9 years in 2013 compared with 14.3 in 2001) and the proportions of secondary school students aged 12–17 who reported smoking in their lifetime, in the past 4 weeks, past week or on 3 days of the last 7, continues to decline (White & Williams 2015) (see 'Chapter 4.7 Tobacco smoking').

Figure 6.1.1: Daily smokers aged 14 and over and key tobacco control measures, Australia, 1990–2016

Source: Department of Health 2015c.

Preventing chronic disease

Chronic diseases, such as coronary heart disease, cancer and diabetes, are the leading causes of illness, disability and death in Australia, and accounted for 17 of the 20 top causes of death in 2013 (see 'Chapter 3.3 Chronic disease and comorbidities'). Strategies to help reduce the impact of chronic disease and associated risk factors are a focus for all Australian governments.

Key risk factors associated with chronic disease include poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, high body mass and high blood pressure (see 'Chapter 3.1 Burden of disease and injury in Australia' and 'Chapter 4 Determinants of health'). These risk factors are largely preventable and can be reduced or eliminated through behavioural changes or managed with medical treatments (for example, medication for high blood pressure). Population health strategies targeting risk factors are wide-ranging, from guidelines and legislation to health programs and media campaigns (see Box 6.1.1 for examples in relation to diet).

Box 6.1.1: Population health approaches targeting diet and nutrition

- Australian Dietary Guidelines

- Mandatory fortification, for example folate fortification of bread

- Legislative instruments (for example Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code; mandatory food labelling)

- Policy and programs for healthy eating and good nutrition in schools

- National campaigns such as the Swap It, Don't Stop It campaign (2008) and the Go for 2&5 campaign (2005)

- Initiatives such as the National Heart Foundation 'Tick' endorsement program and other food labelling (beginning 1989) and the Health Star Rating System (2014)

What is missing from the picture?

Evaluating the impact and cost of community and nationwide initiatives can be difficult. Directly attributing outcomes to a specific initiative can also be a challenge, especially when multiple strategies are being applied at once (for example, legislation, taxation and promotion campaigns). Adding to this challenge is the fact that the impact of an intervention will often be delayed, meaning evidence to support the effectiveness of prevention activities may not be available for many years.

Vaccinations are recorded in Australia for children up to the age of 7, but there is no register for adults. The national system for recording childhood vaccinations is the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register (ACIR). A 'whole-of-life' Australian Immunisation Register will be introduced during the second half of 2016, starting with expansion of the ACIR to record vaccines delivered during adolescence (NCIRS 2015).

Where do I go for more information?

More information on the Immunise Australia Program is available at Department of Health website. The reports National Drug Strategy Household Survey detailed report: 2013 and Australia's food and nutrition 2012 are also available for free download.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2016. National health expenditure, current and constant prices, 1985–86 to 2013–14, data cube. Canberra: AIHW.

BITRE (Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics) 2010. Road deaths in Australia 1925–2008. Canberra: BITRE.

BITRE 2015. Road trauma Australia, 2014 statistical summary. Canberra: BITRE.

Department of Health 2015a. Immunise Australia Program. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 15 October 2015.

Department of Health 2015b. Immunise Australia Program. Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 31 March 2016.

Department of Health 2015c. Tobacco key facts and figures. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 23 October 2015.

Department of Health 2016a. Immunise Australia Program. ACIR current data. Canberra: Department of Health.

Department of Health 2016b. Immunise Australia Program. ACIR current data: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Canberra: Department of Health.

Department of Health 2016c. Immunise Australia Program. Immunisation coverage targets. Canberra: Department of Health.

Gruszin S, Hetzel D & Glover J 2012. Advocacy and action in public health: lessons from Australia over the 20th century. Canberra: Australian National Preventive Health Agency.

Hector D 2011. Sydney's water sewerage and drainage system. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 144:3–25.

NCIRS (National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance) 2014. Evaluation of the National Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Program: final report.

NCIRS 2015. Adult vaccination: fact sheet. Vaccines for Australian adults: information for immunisation providers, August 2015. Sydney: NCIRS.

NHPVVPR (National HPV Vaccination Program Register) 2015. Coverage data. Melbourne: NHPVVPR.

Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, Skinner SR, Cummins E, Liu B et al. 2012. Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. Journal of Infectious Diseases 206(11):1645–51.

White V & Williams T 2015. Australian secondary school students' use of tobacco in 2014: report. Report prepared for the Tobacco Control Taskforce and the Australian Government Department of Health. Melbourne: Cancer Council of Victoria.

6.2 Cancer screening

Population-based cancer screening is an organised, systematic and integrated process of testing for signs of cancer or pre-cancerous conditions in populations without obvious symptoms. In Australia, there are national population-based screening programs for breast, cervical and bowel cancers. They are run through partnerships between the Australian Government and state and territory governments. The programs target particular populations and age groups where evidence shows screening is most effective at reducing cancer-related morbidity and mortality.

BreastScreen Australia

BreastScreen Australia, established in 1991, provides free, 2-yearly screening mammograms (see Glossary) to women aged 40 and over, and actively targets women aged 50–74.

The target age group for BreastScreen Australia was expanded from women aged 50–69 to women aged 50–74 from 1 July 2013. The target age group 50–69 is used here because during the years reported, most data were collected when only women aged 50–69 were actively targeted.

- High attendance for screening is needed to maximise the number of breast cancers detected early, and subsequent reductions in mortality from breast cancer.

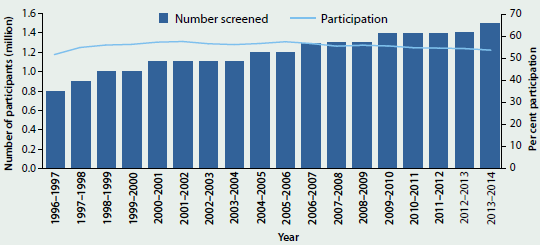

- In 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, more than 1.4 million women aged 50–69 participated in BreastScreen Australia, which is around 55% of the population.

- Participation was lower among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, at around 36% of the population in 2012–2013, as well as among women living in Very remote areas (47%) and women from a culturally or linguistically diverse background (49%).

- Over time, participation in BreastScreen Australia has remained relatively steady, being around 55–57% between 1996–1997 and 2011–2012, before falling slightly to 54% in the latest available reporting periods of 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 (Figure 6.2.1).

- More than half of all breast cancers detected through BreastScreen Australia are small, and small breast cancers are associated with more treatment options and improved survival.

National Cervical Screening Program

The National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP), established in 1991, targets women aged 20–69 for a 2-yearly Papanicolau smear, or 'Pap test' (see Glossary).

- High attendance for screening means that more cervical abnormalities can be detected and treated that could otherwise develop into cervical cancer, leading to a reduction in cervical cancer incidence and mortality.

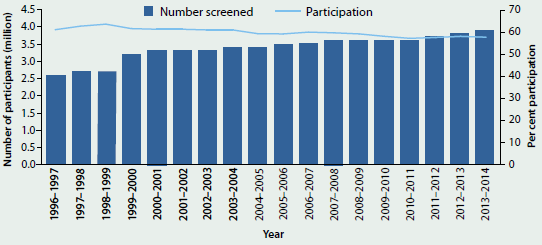

- In 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, more than 3.8 million women aged 20–69 participated in the NCSP, which is around 58% of the eligible population.

- Participation in 2012–2013 was similar across remoteness areas—highest in Inner regional areas (60%) and lowest in Very remote locations (55%), but increased with increasing socioeconomic position (from 52% in the lowest socioeconomic group to 64% in the highest group).

- Participation has remained steady since 2004–2005 at around 57%–59% (Figure 6.2.2).

- For every 1,000 women screened, around 8 have a high-grade abnormality detected, providing an opportunity for treatment before possible progression to cervical cancer.

Figure 6.2.1: Number of women screened and age-standardised participation rate, BreastScreen Australia, 1996–1997 to 2013–2014

Sources: AIHW analysis of BreastScreen Australia data; AIHW analysis of state and territory cervical cytology register data.

Figure 6.2.2: Number of women screened and age-standardised participation rate, National Cervical Screening Program, Australia, 1996–1997 to 2013–2014

Sources: AIHW analysis of BreastScreen Australia data; AIHW analysis of state and territory cervical cytology register data.

National Bowel Cancer Screening Program

The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP), established in 2006, currently targets men and women turning 50, 55, 60, 65, 70 and 74, inviting them to screen for bowel cancer using a free faecal occult blood test (FOBT) (see Glossary). In 2014, the Australian Government announced that the program was to be expanded, and once fully implemented in 2020 would offer free 2-yearly screening for all Australians aged 50–74.

From 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014, 1.4 million FOBT invitation kits were issued to eligible Australians. Of these:

- nearly 510,000 returned a completed FOBT kit for analysis—a participation rate of 36%. Participation was higher among women (39%) than men (34%)

- of the people who returned a valid screening test, 7.5% returned a FOBT with a positive screening result and 68% of those had a follow-up colonoscopy (see Glossary) recorded

- of those participants who underwent a colonoscopy, 1 in 25 were diagnosed with a confirmed or suspected bowel cancer, and 1 in 11 were diagnosed with an advanced adenoma (pre-cancerous tumour).

What is missing from the picture?

National cancer data do not include whether a new case of cancer was identified through screening.

Participation in cervical screening cannot be measured nationally for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women as Indigenous status is not included on all pathology forms in all states and territories, which is the only source that provides information to cervical screening registers. However, available evidence on the participation in cervical screening by Indigenous women suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait women are under-screened.

What is the AIHW doing?

A recent AIHW study compared bowel cancer outcomes of those invited to participate in the NBCSP with those of similar age who had not yet been invited. To do this, data from the NBCSP were linked to the Australian Cancer Database and the National Death Index data set. Of people aged 50–69 who were diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2006–2008, those without a previous NBCSP invitation had a 15% higher risk of dying from bowel cancer by 2012 than those diagnosed after a NBCSP invitation. The study found that bowel cancers diagnosed in non-invitees were, on average, more likely to be at a more advanced stage of cancer development. It is planned that this study will be updated with additional years of cancer incidence and mortality data in the next few years.

Where do I go for more information?

The BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2012–2013, Cervical screening in Australia 2012–2013 and National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: monitoring report 2013–14 are available for free download.

6.3 Primary health care

In Australia, primary health care is typically the first contact an individual with a health concern has with the health system. 'Primary health' broadly encompasses health care that is not related to a hospital visit, and includes activities such as health promotion, prevention, early intervention, treatment of acute conditions, and management of chronic conditions (Department of Health 2015d).

Primary health services are delivered in settings such as general practices, community health centres, allied health practices, and through communication technology such as telehealth and video consultations. General practitioners (GPs), nurses, nurse practitioners, allied health professionals, midwives, pharmacists, dentists, and Aboriginal health practitioners are all considered primary health care professionals.

What is the scale and nature of primary health care delivery in Australia?

The vast majority of health care services in Australia are delivered in primary health care settings. For example, in 2014–15, there were:

139 million non-referred encounters with GPs claimed through Medicare—from a total of 335 million out-of-hospital services. Other Medicare-funded out-of-hospital services included pathology and allied health such as physiotherapy (Department of Health 2015a). 17% increase from 119 million non-referred encounters with GPs in 2010–11.

139 million non-referred encounters with GPs claimed through Medicare—from a total of 335 million out-of-hospital services. Other Medicare-funded out-of-hospital services included pathology and allied health such as physiotherapy (Department of Health 2015a). 17% increase from 119 million non-referred encounters with GPs in 2010–11.

117 million medications were prescribed by a GP and a further 11 million medications were provided directly. to the patient (Britt et al. 2015). 17% increase from 100 million medications prescribed by GPs in 2010–11.

117 million medications were prescribed by a GP and a further 11 million medications were provided directly. to the patient (Britt et al. 2015). 17% increase from 100 million medications prescribed by GPs in 2010–11.

3.5 million episodes of care were delivered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific services. 42% increase from 2.5 million episodes of care in 2010–11.

3.5 million episodes of care were delivered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-specific services. 42% increase from 2.5 million episodes of care in 2010–11.

In comparison, Australian public hospitals provided around 18 million occasions of service for outpatient care in 2013–14 (excluding Victoria, which provided 3.7 million occasions of service in 2012–13). In 2013–14, public hospitals also provided 5.7 million episodes of admitted care (hospitalisations), and responded to 7.2 million emergency department presentations (see 'Chapter 6.11 Emergency department care').

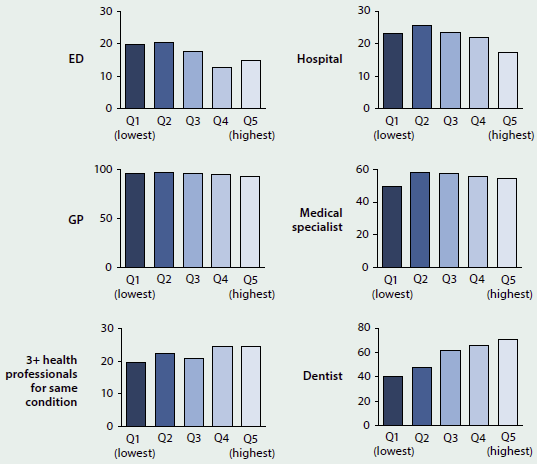

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2014–15 Patient Experience Survey showed:

- more than 4 in 5 people (83%) had consulted a GP at least once in the previous 12 months, and females were more likely than males to see a GP (88% and 78%, respectively)

- almost 1 in 5 (18%) saw three or more health professionals for the same health condition

- about 1 in 11 (8.7%) had seen an after-hours GP in the previous 12 months

- almost 1 in 2 (49%) had seen a dental professional in the previous 12 months (ABS 2015).

About $55 billion of total health expenditure was spent on primary health care in 2013–14. This equates to 38% of total health funding and was similar to spending on hospital services (40%).

How is primary health care in Australia changing?

The health care system in Australia faces a number of ongoing challenges, including the provision of effective and coordinated care, an ageing population, rising prevalence of some risk factors such as obesity and physical inactivity, and increased incidence of chronic disease and multiple chronic diseases (see 'Chapter 2.1 How does Australia's health system work?' and 'Chapter 3.3 Chronic disease and comorbidities').

During 2014–15, the Australian Government established the Primary Health Care Advisory Group and Primary Health Networks (PHNs) (Box 6.3.1) as part of its reform of the primary health care system. Priorities of the reform program include complex and chronic disease management; better recognition and treatment of mental health conditions; and greater connection between primary health care and hospital care.

Primary health care delivery, efficacy, accessibility and integration with other facets of the health care system may also be informed by and impacted upon by Australian Government-led reviews of:

- after-hours primary health care (Jackson 2014)

- services reimbursed under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (Department of Health 2015b)

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee Guidelines (Department of Health 2015c).

Box 6.3.1: Primary Health Networks

On 1 July 2015, the Australian Government established PHNs with the aim of increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of health services, and to ensure patients receive the right care in the right place at the right time.

The 31 PHNs replace the 61 Medicare Locals, and are aligned with Local Hospital Networks, to assist with the management of patients with complex or chronic conditions between the primary health care and hospital systems. PHNs work directly with GPs, other primary health care providers, secondary care providers, hospitals, and the broader community for the purpose of ensuring better outcomes for patients.

What is missing from the picture?

Primary health care has not experienced the same national focus on data capture, collation and reporting as other parts of the Australian health system. As a result, there is limited or no detailed information on primary health care consultations; national data for ambulance, aeromedical and allied health services; or state-funded community health activity data.

Australia's emerging e-Health system may provide an additional source of data to improve our understanding of primary health care; however, the extent of this contribution is not yet clear. Other means of improving primary health care information include improving GP surveys or improving the extraction and analysis of core GP data; making better use of existing national data in reporting at the PHN level, and collating existing data for reporting at the national level; and assessing the benefits of data linkage to report on patient journeys through the health system.

Where do I go for more information?

More information on primary health care in Australia is available in previous editions of this report, including Australia's Health 2014, which can be downloaded for free. In addition, further information is available at Primary health care.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2015. Patient experiences in Australia: summary of findings, 2013–14. ABS cat. no. 4839.0. Canberra: ABS.

Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Bayram C, Harrison C, Valenti L et al. 2015. General practice activity in Australia 2014–15. General practice series no. 38. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Department of Health 2015a. Annual Medicare statistics. Canberra: Department of Health.

Department of Health 2015b. Medicare Benefits Schedule Review. Canberra: Department of Health.

Department of Health 2015c. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee Guidelines Review. Canberra: Department of Health.

Department of Health 2015d. Primary care. Canberra: Department of Health.

Jackson C 2014. Review of after hours primary health care. Report to the Minister for Health and Minister for Sport. Canberra: Department of Health.

6.4 Medicines in the health system

Medicines are used to treat, prevent and manage a wide range of health conditions. Some require prescriptions; others can be bought without a prescription over the counter at a pharmacy or through other retail outlets such as supermarkets. Data on medicines are mainly available for medications available through these community outlets and come from Australian Government subsidy schemes, the Pharmacy Guild of Australia and from market surveys for over-the-counter goods purchased from pharmacies and supermarkets. There is little information collected nationally regarding the medications provided to patients by hospitals, apart from information from the Australian Government Section 100 program which allows supply of restricted medicines under a special arrangement in public and private hospitals (Department of Health 2015b).

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS) are the two main government subsidy schemes for medicines. The PBS and RPBS specify a price for each listed pharmaceutical to be paid to the pharmacy when dispensing the medication. This price includes an amount to cover the services provided by the pharmacist, as well as the cost of the pharmaceutical. Consumers pay out-of-pocket costs up to a maximum copayment limit ($38.30 for general patients or $6.20 for concession card holders).

Medicines dispensed through the PBS and RPBS

The best available data on the dispensing of medicines comes from the PBS and RPBS and the most recent financial year with data on the total number of dispensed PBS and RPBS prescriptions is 2014–15. In 2014–15, there were nearly 225 million subsidised prescriptions dispensed under the PBS and RPBS that were priced over the maximum copayment limit. This was an increase of 21% from 185 million in 2004–05 (DHS 2015). In the same period, Australia's population increased from 20.0 million to 23.3 million people, a growth of 16%. About 91% of PBS services in 2014–15 were provided to concession card holders.

Some of the medicines dispensed under the PBS and RPBS are dispensed at a price less than the maximum copayment and do not attract a government subsidy. In 2013–14, the most recent year with data on these under-copayment medicines, there were 72 million prescriptions dispensed under the copayment level (Department of Health 2015a). This is in addition to the 210 million subsidised medicines in 2013–14. This was an increase from 62 million in 2012–13. Prior to 1 April 2012, data on PBS prescriptions priced below the copayment level were not collected by the Australian Government.

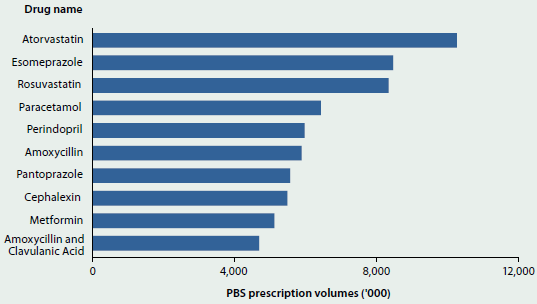

In 2013–14, of all drugs dispensed under the PBS or RPBS, including those where there was no subsidy from the Government, the most commonly dispensed groups of drugs were cholesterol-lowering drugs (atorvastatin and rosuvastatin); drugs treating gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (esomeprazole and pantoprazole); and antibiotics (amoxycillin, cephalexin, and amoxycillin with clavulanic acid) (see Figure 6.4.1). The analgesic paracetamol and the anti-hypertensive perindopril were also commonly dispensed. Metformin, a drug used for treatment of diabetes, was the ninth highest prescribed drug.

Figure 6.4.1: PBS and RPBS dispensed drug volumes, including under- and over-copayment prescriptions, 2013–14

Source: Department of Health 2015a.

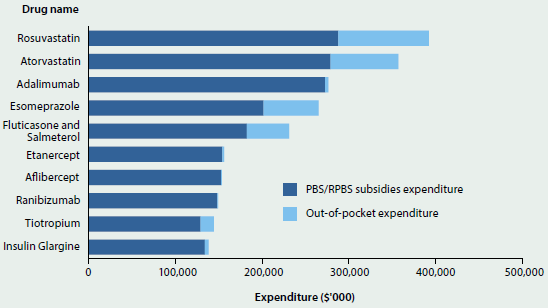

Cholesterol-lowering drugs also had the highest total expenditure in 2013–14 of all drugs under the PBS and RPBS (see Figure 6.4.2). Other high-expenditure drugs were those used for the treatment of severe arthritis (adalimumab and etanercept); the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (esomeprazole); the management of respiratory disorders (fluticasone with salmeterol and tiotropium); the treatment of macular degenerative disorders (aflibercept and ranibizumab); and for long-acting control of blood sugar levels in diabetics (insulin glargine).

Figure 6.4.2: PBS and RPBS dispensed drug expenditure, including under- and over-copayment prescriptions, 2013–14

Source: Department of Health 2015a.

In 2013–14, more than half of the drugs subsidised through the PBS and RPBS—that is, drugs where the cost was above the maximum copayment level and there was a subsidy paid by government—affected the cardiovascular system (31%) or the nervous system (22%). In 2003–04, the subsidised drugs most supplied were also medicines for the cardiovascular system and nervous system, but these made up a lower proportion of the total subsidised medicines (30% and 18%, respectively) (Department of Health 2015a).

According to the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health survey of general practice, antibiotics and analgesics (used for pain relief) were the medicines most commonly prescribed by general practitioners in 2013–14. It is not known whether these were then dispensed through the PBS or RPBS. This pattern has not changed since 2003–04 (Britt et al. 2015).

Medicines expenditure

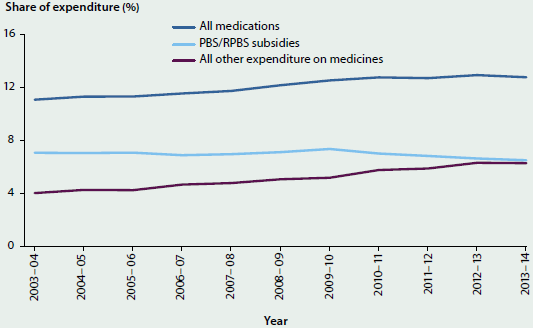

Expenditure on medicines grew in absolute terms, from $10.3 billion in 2003–04 to $19.8 billion in 2013–14, and as a proportion of recurrent health expenditure, from 11% in 2003–04 to 14% in 2013–14. The estimate of the expenditure on medicines includes expenditure by the Australian Government, such as expenditure on medicines subsidised through the PBS and RPBS, and non-government expenditure, which includes expenditure on below-copayment prescriptions. Apart from expenditure on medicines dispensed in hospitals under the Section 100 provisions, it does not include expenditure on medicines supplied in hospitals, which is regarded as hospital expenditure.

The growth in medications expenditure was mostly related to expenditure for non-PBS and non-RPBS subsidised medicines, referred to as All other expenditure on medicines, which is mostly non-government expenditure such as expenditure on over-the-counter medicines and below-copayment prescriptions. However, it includes some government expenditure such as incentive payments to pharmacies to process prescription subsidies using PBS Online, and payment for medicines provided under the Life Saving Drugs program. All other expenditure on medicines rose from 4.2% of recurrent health expenditure in 2003–04 to 6.7% in 2013–14. PBS and RPBS subsidies reduced from 7.4% of recurrent health expenditure in 2003–04 to 6.7% in 2013–14 (Figure 6.4.3).

In real terms, PBS and RPBS expenditure generally increased since 2003–04, but decreased recently, from $9.1 billion in 2011–12 to about $9 billion in 2013–14.

Lower expenditure does not necessarily mean fewer prescriptions dispensed. The volumes of prescriptions subsidised increased from 201 million government-subsidised medicines dispensed in 2011–12 to 210 million in 2013–14.

Figure 6.4.3: Proportion of recurrent health expenditure on medications, constant prices, 2003–04 to 2013–14

Source: AIHW health expenditure database.

What is missing from the picture?

In most cases where a medicine is dispensed there is little information captured and collated at a national level on the purpose for which it was prescribed, whether the medicine was taken, and the outcome that occurred from use of the medicine. This information at the patient level would greatly enhance monitoring of the use of medicines in Australia.

Nationally collected information on all medicines provided through hospitals would add extra understanding of the use of medicines in Australia and expenditure on them.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on medicine statistics in Australia, visit the Medicare Statistics website.

References

Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Bayram C, Harrison C, Valenti L et al. 2015. General practice activity in Australia 2013–14. General practice series no. 38. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

DHS (Department of Human Services) 2015. Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule group reports. Canberra: DHS.

Department of Health 2015a. Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2014. Canberra: Department of Health.

Department of Health 2015b. Section 100—items available under special arrangement. Canberra: Department of Health.

6.5 Using data to improve the quality of Indigenous health care

For nearly a decade now, the AIHW has collected data from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care organisations for national performance reporting. Over this time there have been major developments in the processes used to collect the data, as well as an expansion of the content and scope of the data collection.

The national data are collected directly from Indigenous health care providers and there is now a rich source of information on the quality of health care from the organisation level upwards. These data allow primary health care organisations to track their performance over time, and for comparing the performance of organisations against peers. This type of data is increasingly being used to drive improvements in the quality of health care provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

This feature article describes some of the national data developments in the Indigenous primary health care sector and how these data are being used. It also includes two case studies from the sector that show how data has been used to improve the quality of health care.

Indigenous primary health care data

Primary health care is generally the first point of contact that people have with the health system and is also the gateway to access other health services. It includes most services not delivered by hospitals, and encompasses a range of providers and services across public, private and the non-government sectors (AIHW 2014a). There are, however, only limited data available on the delivery of primary health care in Australia. An exception to this is the Indigenous primary health care sector where regular and comprehensive performance data are collected.

It is particularly important that Indigenous Australians have good access to primary health care services because of their poorer health (AIHW 2011). The Australian Government provides funding to organisations to provide primary health care to Indigenous Australians. Many of these organisations are Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations which provide access to a range of primary health care services, including prevention, diagnosis, treatment and referral, in one location.

At the national level, organisations funded by the Department of Health to provide primary health care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are required to report six-monthly organisation-level data for the national key performance indicators (the nKPIs) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care. There are similar efforts in place for organisations funded by state and territory governments, for example the Northern Territory Aboriginal Health Key Performance Indicators (NTAHKPIs) which have been in place since July 2009. This means that data are regularly collected about how individual services are performing, along with comparative data from other services. These data have increasingly been used to improve the quality of health care provided to consumers at the service level through formal continuous quality improvement (CQI) or other quality improvement processes (Box 6.5.1).

Box 6.5.1: Continuous quality improvement in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care

Continuous quality improvement is a process of using objective information at the health service level to understand and improve the quality of care that clients are receiving. It is an iterative process that includes the collation and analysis of patient and provider data to measure service level activities, and the identification of needs and gaps in these activities by comparing these data against an agreed set of standards.

The Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle is a key component of CQI, a process where health services assess their present service delivery against objective criteria, plan and implement changes, and then reassess their progress. This cycle allows ongoing improvements to specifically meet the priority health outcomes identified by individual services.

There are a number of CQI initiatives operating in the Indigenous primary health care sector at national, state/territory and regional levels, driven from the state, territory and national governments and from frontline services upwards. At the national level there are the Australian Primary Care Collaboratives, One21seventy and Healthy for Life initiatives, while state-based initiatives include the Northern Territory CQI Strategy and the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council Achieving Clinical Excellence program.

The uptake of CQI initiatives in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care has, however, not been uniform across Australia. Recognising these disparities, the Department of Health commissioned a first report that outlined the current state of play in relation to CQI activity and evidence, and identified barriers and linkages relevant to the development of a national CQI framework (Lowitja 2014). A second stage, involving the development of the national CQI framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care, is currently under way.

Sources: Bailie et al. 2007; Lowitja Institute 2014.

The nKPIs

The nKPIs are a set of indicators developed under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement. The nKPIs focus on maternal and child health, and chronic disease management, and were designed to support the Council of Australian Governments Closing the Gap targets: to close the gap in life expectancy within a generation and to halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under 5 within a decade. The nKPI data are collected from organisations that provide primary health care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The AIHW is responsible for the ongoing collection and reporting of these indicators.

The nKPIs were developed based on the experience of the Healthy for Life program (HfL), and many of the initial nKPIs had forerunners in the HfL Essential Indicators (Box 6.5.2). They embedded the concept of CQI in their design, with a focus on measuring and improving health service processes and outcomes that were specifically related to the quality of care provided to clients.

Box 6.5.2: The Healthy for Life program

The HfL program was introduced by the Australian Government in 2005–06 to improve the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers, babies and children; to improve the early detection and management of chronic disease; and to reduce the incidence of adult chronic disease. HfL pioneered the collection of national health data specifically for CQI processes and to improve health care delivery (AIHW 2013).

An external evaluation of the HfL program, conducted by Urbis in 2009, found considerable evidence of a wide range of improvements that services had made to health service systems, practices and service delivery as a result of HfL funding. A significant legacy for most participating services was the improvement in their capacity to collect, report and act on good quality data that reflected the processes and outcomes of their service (Urbis 2009).

The evaluation report noted that HfL provided a model for other program areas in aggregating local-level data for national reporting and establishing reporting frameworks that demonstrate tangible population-level outcomes (Urbis 2009). The evaluation found that the program had led to a wide range of service quality improvements such as:

- improved physical access to care—including through transport services and visiting community members in their homes, in hospitals and in schools

- new approaches to care delivery—including targeted clinics such as diabetes clinics, peer support programs and other initiatives that support healthy living

- new approaches to care planning and coordination—including new program areas, individualised care planning, internal coordination activities and improved relationships with other agencies (Urbis 2009).

Sources: AIHW 2013; Urbis 2009.

The nKPIs are categorised as either process-of-care indicators or outcome indicators (for more information about the indicators see the AIHW nKPI website.) The process-of-care indicators, in particular, reflect activities that are largely under the control of organisations, for example Birthweight recorded or Smoking status recorded (AIHW 2015c). The number of indicators in the nKPI collection increased progressively, from 11 in the first reporting round in June 2012 to 21 indicators in the December 2014 reporting round.

An electronic data extraction tool extracts aggregate nKPI data directly from the health organisations' clinical information systems and this is submitted to OCHREStreams, a web portal from which the AIHW can access the data. The AIHW then works with health care organisations to improve their data quality, in a process of data checking and resubmission, before it is used to meet various reporting requirements.

The number and scope of services providing nKPI data has increased over time. The first collection round only included services participating in the HfL program (about 90 services) and in January 2013 this was expanded to include all Indigenous primary health services funded by the Australian Government. Services funded by the Northern Territory Government were included in the collection from December 2014, when 233 services provided nKPI data (Table 6.5.1).

| Governance arrangement | NSW/ ACT |

Vic/ Tas |

Qld | WA | SA | NT | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Organisations | 40 | 26 | 21 | 17 | 10 | 20 | 134 | 57.5 |

| State and territory governments | 13 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 54 | 83 | 35.6 |

| Medicare Locals(a) | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 5.6 |

| Other non-government | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.3 |

| Total | 63 | 30 | 28 | 22 | 16 | 74 | 233 | 100.0 |

- Medicare Locals were abolished in 2014 and replaced by Primary Health Networks.

Source: AIHW nKPI collection.

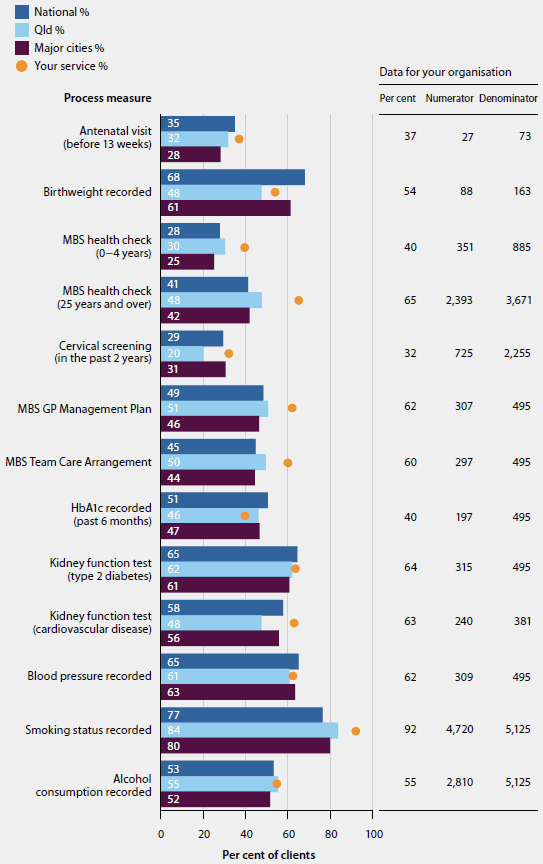

Reports provided to organisations

The AIHW provides organisations that submit data with a written report and PowerPoint presentation specifically for their service. These show the data for the relevant reporting period, time series data and national, state/territory and regional averages for use in comparing and assessing their own performance (Figure 6.5.1). This information allows services to track their performance relative to others and over time. It can be readily used by the organisation for a range of purposes including CQI, staff training and as input for Board or executive meetings.

Tracking organisations' performance

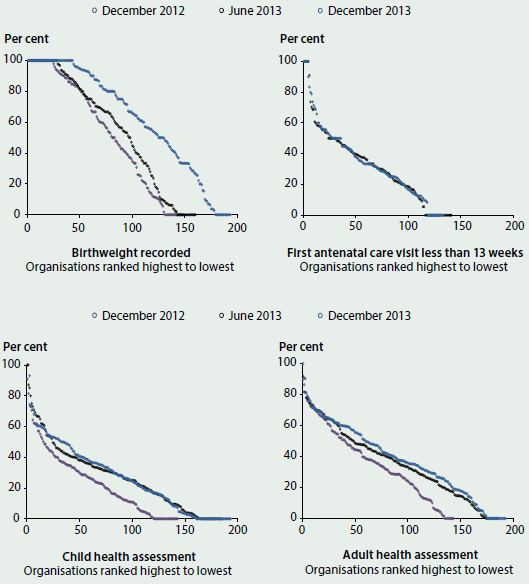

The AIHW produces national reports and presentations based on the aggregated nKPI data (AIHW 2014b, 2014c, 2015c). The national reports show that performance on most of the nKPIs has improved over time, but there is a wide variation in organisations' performance for most indicators.

For example, the national nKPI reports include graphs of where individual services fit within the national distribution for all process-of-care indicators (Figure 6.5.2). The performance of each organisation is represented as a point on the graph and this can range widely depending on the indicator and what proportion of clients have been provided with a particular service. The shape of the curve reflects this distribution and the three lines show how the performance distribution has changed over time, relative to the first reporting period.

Figure 6.5.1: Examples of nKPI organisation-level and comparison data

Figure 6.5.2: Distribution of performance of all organisations on selected nKPI indicators

Note: Organisation performance can range from 0 to 100% on each nKPI for the relevant reporting period, with 100% being the optimal score. The performance of each organisation is represented by a dot on the graph for the relevant nKPI.

Source: AIHW 2014c.

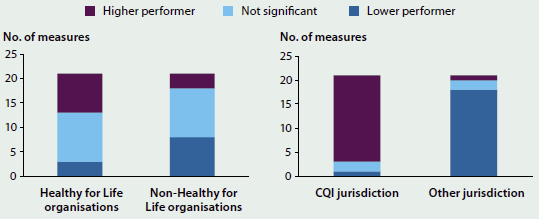

Analyses of the variation in performance over time showed that clients at organisations that had participated in HfL—the national CQI program—had better results than clients at other organisations. The clients attending HfL organisations had better results than those attending non-HfL organisations on eight measures, while clients at the non-HfL organisations had better results on only three measures. Similarly, clients at organisations in jurisdictions with a history of using CQI processes (that is, the Northern Territory and Queensland) had better results than clients at organisations that did not use these processes (Figure 6.5.3) (AIHW 2014b).

Figure 6.5.3: Comparison of organisation performance on nKPIs over three reporting periods, June 2012–June 2013

Note: Graphs compare the performance of the two types of organisations (HfL and non-HfL; CQI and other jurisdiction) and show the number of measures where they performed higher or lower than each other.

Source: AIHW 2014b.

Case studies

Northern Territory Department of Health

The Northern Territory Aboriginal Health Forum developed the NTAHKPIs for monitoring service delivery and improvement in maternal and child health programs, as well as early intervention and chronic disease management. Making these data visible has been a critical element of service improvement for health care services delivered by Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations as well as for the Northern Territory Government.

The indicators are used by policy and program staff to identify areas of concern and target areas where improvements can be made across the Territory. Strategies are then put in place to address these. Health care services with strong performance in a particular area can also be identified, and the strategies they used to obtain these results are shared with other services.

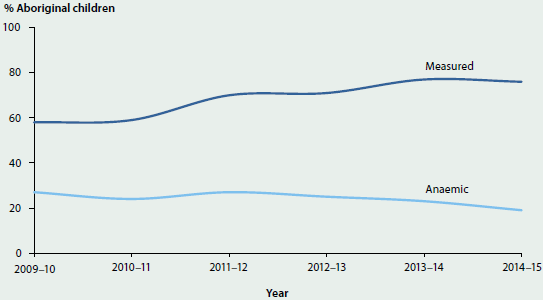

In the area of improving childhood iron deficiency and anaemia, for example, persistent high rates were noted in the NTAHKPIs. The data showed the range of performance across organisations and indicated that improvements in service delivery were possible. A combination of strategies was used to address the issue:

- The Northern Territory Department of Health developed and led a more systematic approach and monitored progress with monthly data

- the Northern Territory CQI Collaborative led by Aboriginal Medical Services NT held forums bringing together clinicians, managers and policymakers to learn from successful services and to train and motivate staff

- a regional approach was used in Katherine with three collaborating Aboriginal health services and in East Arnhem through a clinical advisory group.

The outcome of these strategies could then be tracked through the indicator results for anaemia. These showed that there was a large increase across organisations in the proportion of children assessed (with the range 29% to 96% in 2012–13 rising to 49% to 96% in 2014–15) and a decline in the proportion of Aboriginal children recorded as being anaemic (the range 18% to 41% in 2012–13 falling to 11% to 30% in 2014–15) (Figure 6.5.4).

Figure 6.5.4: Performance indicator results for anaemia, Northern Territory

Source: NT Department of Health presentation, unpublished.

The Goondir Health Service Dashboard

Goondir Health Service has developed its own visually appealing and easy-to-use electronic reporting system to improve service delivery. The service is located in regional Queensland and operates multiple clinics across 160,000 kilometres. The Clinical Performance Dashboard is a service-planning and management tool that brings together three types of data: clinical data from the patient information recording system, organisational data from the quality management system, and financial data. It provides clinicians, managers and the executive with up-to-date data to inform clinical and management decisions (Hansford 2015).

The dashboard provides different levels of information, beginning with high-level summary data, and then allows users to 'drill down' to more detailed views of key measures. The first level includes measures such as patient numbers, appointments, services delivered and performance indicator results (Figure 6.5.5). Large ticks are used to indicate where the service is on target or improving and crosses indicate areas that are not doing well.

Figure 6.5.5: Goondir Health Service Clinical Performance Dashboard manager’s snapshot

Note: This image is a low resolution screenshot included to provide an overall impression of the dashboard.

Source: Hansford 2015.

Drilling down further to the performance data, for example, a dashboard summary graph shows trends over time in the number of performance indicators that are improving or not, and then provides a list of the indicators where the service is performing poorly. For example, the health service manager could check how they are performing on smoking rates or the proportion of overweight/obese clients. With this information, health service managers can assess and develop strategies, such as targeted health-promotion activities, to improve performance against these indicators (Hansford 2015).

What is the AIHW doing?

There is an increasing interest in using data to improve health outcomes at the local level, where there can be large variations in the quality of health care delivered. The Indigenous primary health care sector is leading the way in the use of organisation-level data to improve the quality of health care through a variety of different quality improvement strategies.

As detailed in this feature article, the nKPIs contribute to these processes by providing regular standardised indicators and comparison data that can be used by organisations to assess their performance. This is in line with the AIHW's strategic priority to provide value-added feedback to data providers (AIHW 2015a), and its support for individual organisations to improve the quality of their data—and, in turn, the quality of the health care they provide.

Over time, the scope of the nKPI collection is also likely to be widened to include state- and territory-funded services, in addition to the Northern Territory. This will mean better quality data about a wider range of primary health care services provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Where do I go for more information?

More information about the nKPIs available at Indigenous Australians health and welfare publications.

Reports including National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care: first national results for June 2012 to June 2013 and National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health care: results from December2014 available for free download.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. Access to health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Cat. no. IHW 46. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2013. Healthy for Life: results for July 2007–June 2011. Cat. no. IHW 84. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2014a. Australia's health 2014. Australia's health series no. 14. Cat. no. AUS 178. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2014b. National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care: first national results June 2012 to June 2013. National key performance indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care no. 1. Cat. no. IHW 123. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2014c. National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care: results from December 2013. National key performance indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care. Cat. no. IHW 146. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015a. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report—key results 2013–14. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services report no. 6. IHW 152. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015b. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Corporate Plan 2015–16 to 2018–19. Cat. no. AUS 194. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015c. National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care: results from December 2014. National key performance indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care no. 3. Cat. no. IHW 161. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015d. The nKPI data collection: data quality issues working paper 2012–2014. Cat. no. IHW 153. Canberra: AIHW.

Bailie R, Griffin J, Kelaher M, McNeair T, Percival N, Laycock et al. 2013. Sentinel sites evaluation: final report. Report prepared by Menzies School of Health Research for the Australian Government Department of Health. Canberra: Department of Health.

Bailie RS, Si D, O'Donoghue L & Dowden M 2007. Indigenous health: effective and sustainable health services through continuous quality improvement. Medical Journal of Australia 186(10):525–27.

Hansford G 2015. How one AMS is closing the gap—the power of data. Paper presented to the 13th National Rural Health Conference, Darwin 24–27 May 2015.

Lowitja Institute 2014. Recommendations for a national CQI Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care. Carlton, Victoria: Lowitja Institute.

Urbis 2009. Evaluation of the Healthy for Life Program: final report. Prepared for: The Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Department of Health and Ageing 30 June 2009.

6.6 Indigenous Australians' access to health services

Access to health services is an important contributor to health and wellbeing. It is a particularly important influence on the health status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, given their overall poorer health and the greater need for health care compared with the non-Indigenous population.

Measuring access to health care is complex, due to its inherently multidimensional nature. 'Access' incorporates measures of physical proximity to services, such as distance or drive time (availability); financial aspects (affordability); and cultural aspects (acceptability). Ideally, assessment of access also includes consideration of need for care. In practice, however, much of the available data on usage of health services by different populations does not fully account for differences in health care needs. Services may be mainstream or targeted to a specific population group (such as specialist Indigenous services). Access to primary health care services is key because it is usually an individual's first point of contact with the health system.

Although three-quarters of the Indigenous population live in Major cities and regional areas where mainstream health services are typically located, these services are not always accessible, for geographic, social and cultural reasons (AIHW 2014b). Indigenous-specific health services are therefore important providers of comprehensive primary health services for Indigenous Australians.

Medicare data provide information on general practitioner (GP) and specialist services claimed for Indigenous Australians. These services can be delivered through mainstream or Indigenous-specific health services, but not all services delivered by Indigenous primary health care services can be claimed through Medicare.

As there are currently no comprehensive data on Indigenous Australians accessing health services, this chapter reviews four selected aspects related to access: (i) an AIHW-developed small-area-level measure of access to primary health care services relative to the distribution of the Indigenous population (ii) health services provided as Indigenous-specific primary health care services, funded by the Australian Government; (iii) health services for Indigenous Australians claimed through Medicare, including selected specialist services; and (iv) hospital services used by Indigenous Australians.

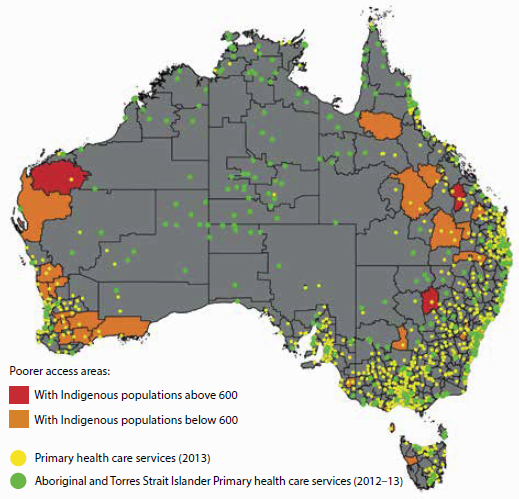

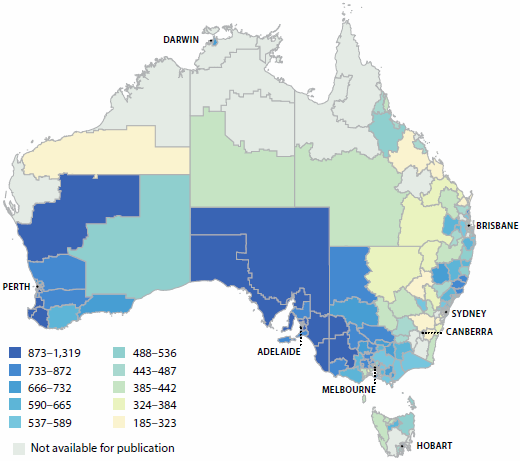

Access to primary health care services relative to population distribution

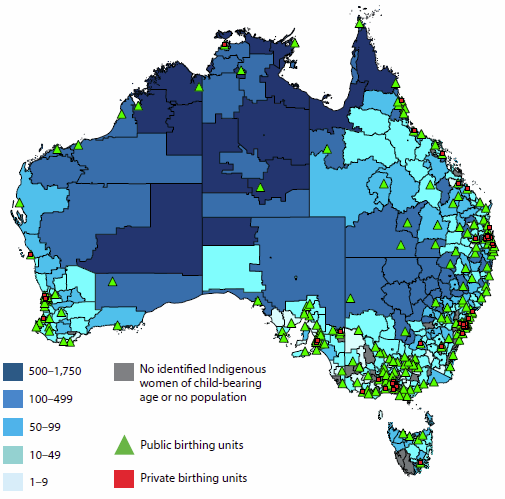

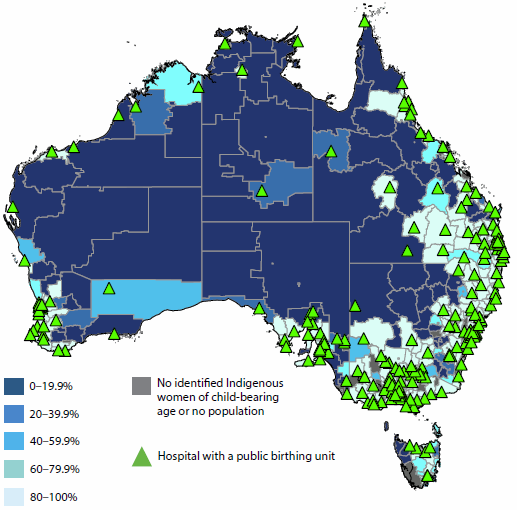

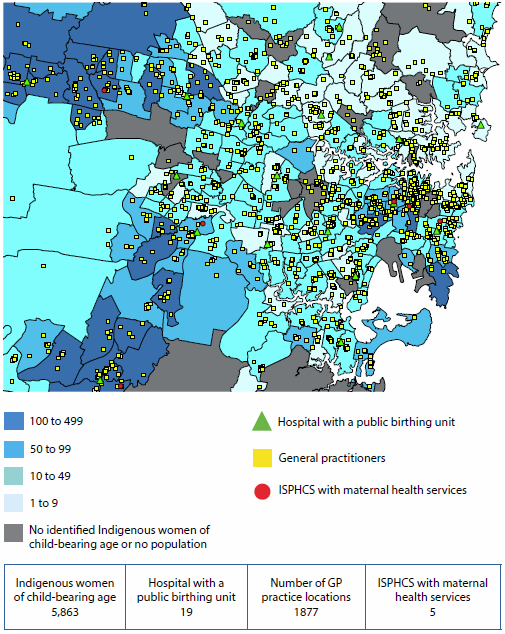

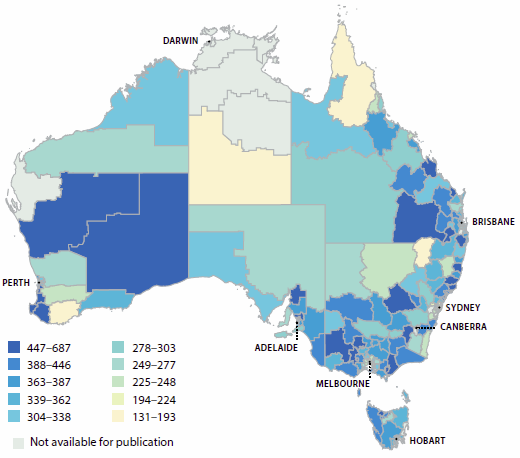

Identifying areas where access is poor can help to inform policy decisions and planning of health services. The AIHW has mapped access to primary health care services (Indigenous-specific primary health care services and other GP-based primary health services) relative to the distribution of the Indigenous population (AIHW 2015b). This has revealed areas where critical primary health care service gaps exist for the Indigenous population (Figure 6.6.1).

Figure 6.6.1: Areas where Indigenous Australians have poor access to primary health care services, by SA2, and location of services, 2012–13 and 2013

Source: AIHW 2015b.

Access to services was measured in terms of: (a) physical access to Indigenous-specific primary health care services based on drive time to services; and (b) physical access to GP services in general, relative to the per capita need for primary health care. The need for primary health care was estimated using demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the local population (AIHW 2014a).

This work shows that, overall, Australian Government-funded Indigenous-specific primary health care services appear to be well positioned relative to the geographic distribution of the Indigenous population, and relative to the distribution of other GP services. There are, however, several areas where the Indigenous population has very limited access to both Indigenous-specific services and GP services in general.

In total, 37 Statistical Areas Level 2 (SA2—medium-sized areas) were identified as service-gap areas, with no Indigenous-specific primary health care services within one hour's drive and with poor access to GP services in general. These service-gap areas are highlighted in red and orange in Figure 6.6.1 (with other areas shown in grey).

- Many of these areas are in Remote and Very remote areas of Queensland and Western Australia.

- Ten of these service-gap areas have an Indigenous population of 600 or more, which are areas shaded in red in the map. (Only three of these red areas are large enough to be clearly seen. Of the remaining seven small areas, six are in Queensland and one is in New South Wales. See AIHW 2015b for details of these locations).

See also 'Chapter 6.7 Spatial variation in Indigenous women's access to maternal health services', which presents more detailed analyses of access to that sub-category of health services.

Use of Indigenous-specific primary health care services

A growing network of Indigenous-specific primary health care services is administered and run by a combination of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations, Primary Health Network services, other non-government organisations, and state/territory local health services. The clients of these services are predominantly, but not exclusively, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

In 2014–15, there were 203 Indigenous-specific primary health care organisations that reported data on their total clients, contacts made, and episodes of care. They provided services to 434,600 clients through over 5 million contacts—an average of 12 contacts per client. Over three-quarters (79%) of these clients identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Over time, the episodes of health care provided to clients of these organisations have almost tripled, from 1.2 million in 1999–2000 to 3.5 million in 2014–15 (AIHW 2016b).

These services provided clinical health care; population health programs; child and maternal health services; screening programs and health checks; access to allied health and specialist services; group activities; health-related community services; and substance-use treatment and assistance.

The national key performance indicators (nKPIs) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care provide information on the process-of-care and health outcomes for clients attending Indigenous-specific primary health care organisations funded by the Australian and state and territory governments. Altogether 24 nKPIs have received in-principle approval from the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council for regular reporting, and data on 22 nKPIs were reported by 233 primary health care organisations for the December 2014 period. These indicators focus on maternal and child health, preventative health and chronic disease management. See also 'Chapter 6.5 Using data to improve the quality of Indigenous health care'.

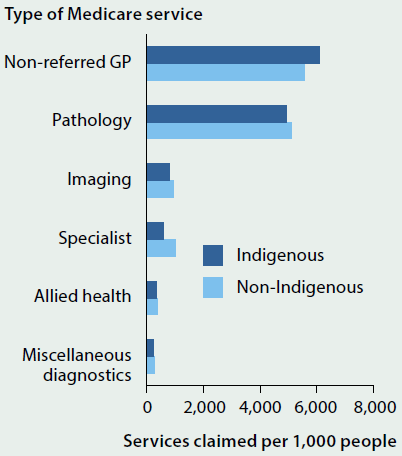

Use of selected health services claimed through Medicare

Medicare data for 2013–14 showed that over 3.6 million GP services had been claimed through Medicare for Indigenous Australians in that year, at an average rate of 6,115 GP services per 1,000 population.

The number of GP services claimed per 1,000 Indigenous Australians was 10% higher than that for non-Indigenous Australians, but claim rates for specialist services were 43% lower for Indigenous Australians (Figure 6.6.2). The lower claim rates for specialist services may be explained partly by the differences in the relative population distributions of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations across urban, regional and remote areas. Access to specialist services is generally lower in more remote areas, and since a greater proportion of the population of remote areas are Indigenous (compared with other areas) this difference affects their overall access to specialist services.

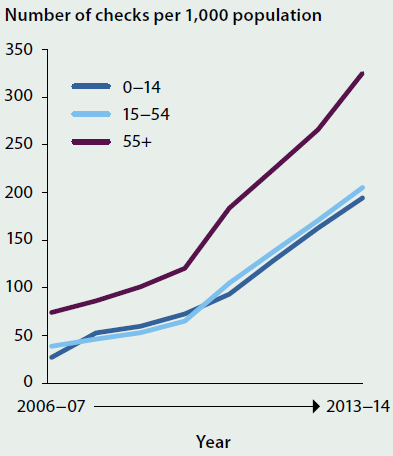

The uptake of the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item for annual health assessments of Indigenous Australians has increased significantly over time (Figure 6.6.3). In 2013–14, primary health care providers carried out:

- 47,400 Indigenous child health checks—a rate of 194 checks per 1,000 Indigenous children aged 0–14

- 80,600 Indigenous adult health checks—a rate of 205 checks per 1,000 Indigenous Australians aged 15–54

- 22,300 Indigenous older-person health checks—a rate of 325 checks per 1,000 Indigenous Australians aged 55 and over.

Figure 6.6.2: Age-standardised rate of Medicare services claimed per 1,000 people, by Indigenous status, 2013–14

Source: AIHW 2015a.

Figure 6.6.3: MBS health checks, Indigenous Australians, by age, 2006–07 to 2013–14

Source: AIHW 2015a.

Hospital services

Indigenous Australians are relatively high users of hospital services, the majority of which are accessed via public hospitals.

- In 2013–14, there were about 408,000 hospitalisations reported for Indigenous Australians, accounting for 4.2% of all hospitalisations.

- After adjusting for differences in age structure, Indigenous Australians were 2.3 times as likely as other Australians to be hospitalised (rates of 896 and 384 per 1,000 population, respectively). Much of this difference (86%) was due to the substantially higher rate of hospitalisations for dialysis among Indigenous Australians (with individuals typically undergoing dialysis treatment multiple times a week).

- Excluding dialysis, Indigenous Australians were hospitalised at 1.2 times the rate of other Australians.

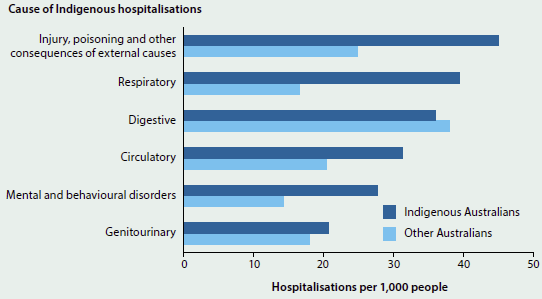

More detailed data on the main causes of hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians in 2013–14, and comparative cause-specific hospitalisation rates (age-standardised) with other Australians, are in Figure 6.6.4.

Figure 6.6.4: Age-standardised rates of the leading causes of Indigenous hospitalisation (excluding dialysis and pregnancy/ childbirth), and comparative rates for other Australians, 2013–14

Source: AIHW 2016a based on analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

- In 2013–14, the leading cause of hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians was injury and poisoning (external causes) (46 hospitalisations per 1,000 people).

- The largest relative difference in hospitalisation rates between Indigenous and other Australians was for respiratory system diseases (2.2 times as high for Indigenous as for other Australians).

- The hospitalisation rate for digestive system diseases was higher for other Australians.

What is missing from the picture?

Comprehensive and complete information on the use of primary health care services or specialist health services by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is not currently available. For example, primary health care services funded only by the state and territory governments do not report regularly on their activities and on the number of their Indigenous clients (apart from the Northern Territory). There is incomplete information on outreach services (which supplement other primary and specialist health services) operating in some parts of Australia. Complete details on Indigenous Australians' use of mainstream health services are also affected by incomplete identification of Indigenous status in the service records. It is therefore not possible to report reliably on the full range of Indigenous patient journeys through the health system.

Australia's emerging e-health system may provide an additional source of data to improve our understanding of the use of primary health care services by both the Indigenous and total Australian populations—however, the extent of e-health records contributing to secondary analyses of data is not yet clear.

Where do I go for more information?

More information on Indigenous people's access to health services can be found on the AIHW's Indigenous Observatory.

More information on geographical variation in Indigenous peoples access to primary health care services can be found in these two AIHW reports: Spatial variation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's access to primary health care, and Access to primary health care relative to need for Indigenous Australians.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2014a. Access to primary health care relative to need for Indigenous Australians. Cat. no. IHW 128. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2014b. Australia's health 2014. Australia's health series no. 14. Cat. no. AUS 178. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015a. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2014 report: detailed analyses. Cat. no. IHW 167. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015b. Spatial variation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's access to primary health care. Cat. no. IHW 155. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2016a. Admitted patient care 2014–15: Australian hospital statistics. Health services series no. 68. Cat. no. HSE 172. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2016b. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report—key results 2014–15. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services report No. 7. IHW 168. Canberra: AIHW.

6.7 Spatial variation in Indigenous women's access to maternal health services

Introduction

The gap between the health of Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander children and non-Indigenous children begins before birth, with Indigenous babies significantly more likely to have been exposed to tobacco smoke in utero, to be born pre-term, and to have a low birthweight (weighing less than 2,500 grams at birth) (AIHW 2015a). Inequalities continue throughout early childhood for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, with higher mortality rates and higher rates of illness and poor health (see 'Chapter 5.2 Trends and patterns in maternal and perinatal health' and 'Chapter 6.6 Indigenous Australians' access to health services').

The factors that contribute to poor infant and child health are complex. These factors include maternal health (for example, maternal weight, pre-existing health conditions); maternal behaviours (smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy, maternal nutrition and breastfeeding); maternal age; social determinants (socioeconomic position and education); and access to health services (such as antenatal care and child health services). Ensuring that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have access to high quality, evidence-based and culturally competent maternal and child health care services has been the goal of a number of state, territory and Australian Government programs and is an important policy issue.

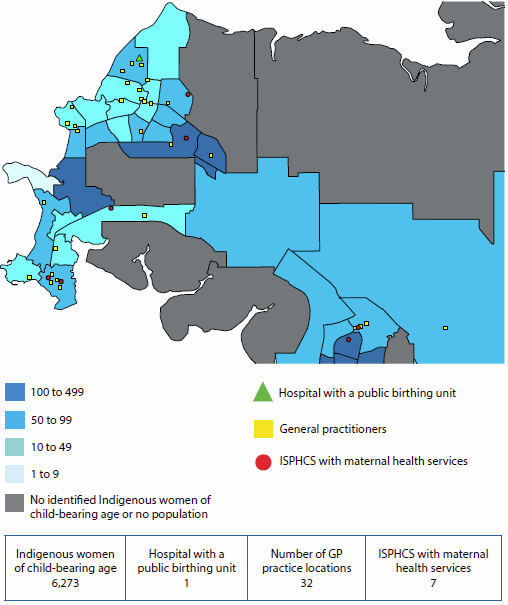

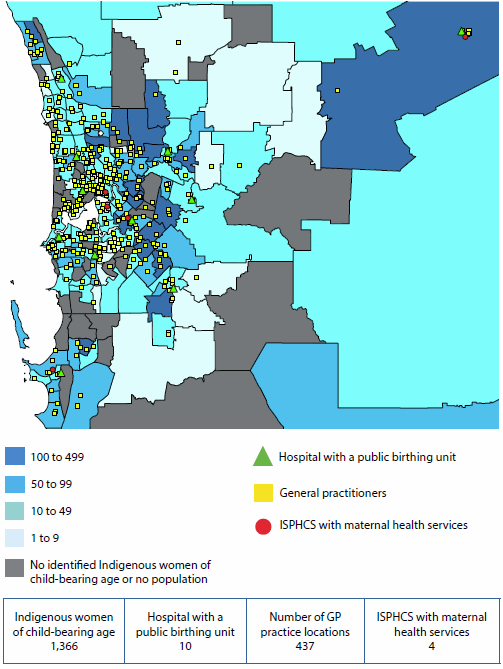

This article highlights the findings from a series of analyses the AIHW has been undertaking which are aimed at identifying geographic areas with potential gaps in services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians (AIHW 2015b), by focusing on Indigenous women's spatial access to two broad types of maternal health services: birthing units within hospitals and antenatal/postnatal services.

Four types of antenatal/postnatal care services are analysed:

- those available from hospitals with a birthing unit

- those provided by Indigenous-specific primary health care services (ISPHCS)

- those available at Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) clinics

- those provided by general practitioners (GPs).

Box 6.7.1 presents an overview of the methodology used to calculate spatial access to maternal health services.

Box 6.7.1: Measuring the spatial accessibility of services

The spatial accessibility of services in this report is measured as the percentage of the relevant population in an area who are within an hour's drive of a particular type of service. Thus, access is measured in terms of physical access only—although even if services are physically accessible, they may not be culturally appropriate or financially accessible or may not be able to provide services when needed due to capacity issues.

The data are presented at the SA2 level (Statistical Area Level 2), which forms part of the Australian Statistical Geography Standard, developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) for the collection and dissemination of geographic statistics. There are 2,214 SA2 areas, with populations between 3000 and 25,000. SA2s are contiguous and cover the entire landmass of Australia. Wherever possible, the SA2 boundaries were based on officially gazetted suburbs and localities. In urban areas SA2s largely conform to whole suburbs and combinations of whole suburbs, while in rural areas they define functional zones of social and economic links.

The percentage of the SA2 population within a one-hour drive from a particular type of service was calculated using several steps (see AIHW 2015b for detailed information on the methodology). The address for each service location was geocoded to a point location then geospatial software was used to calculate the drive time from the manually adjusted population centroid (the point location in an area that aims to represent where people live) of each SA1 (Statistical Area Level 1, the smaller geographic areas that aggregate to an SA2). These results were then used to calculate the proportions of the population within SA2s who were inside or outside a one-hour drive. Women and children living in migratory zones or unable to be classified into an SA2 were excluded from these analyses.

Where do Indigenous women and children live?

The spatial distribution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women of child-bearing age and children is a critical issue for the development and delivery of a range of maternal and child health services.

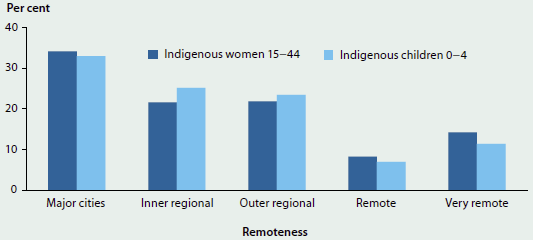

There are an estimated 124,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women of child-bearing age in Australia (ages 15–44), and each year approximately 10% give birth (Hilder et al. 2014). There are also just over 67,000 Indigenous children under 5 years of age. Figure 6.7.1 shows that, while the highest proportions of Indigenous women and young children live in Major cities, over one-fifth (22%) of Indigenous women of child-bearing age live in Remote or Very remote areas, as do nearly one-fifth (18%) of Indigenous children under age 5.

This population distribution is important because distance often poses significant challenges for workforce recruitment and health service delivery in areas outside cities, particularly in areas in which populations are widely dispersed or isolated. While service availability is less of an issue in urban areas, ensuring that these services are culturally appropriate and accessible to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women is essential for effective care.

Figure 6.7.1: Distribution of Indigenous women aged 15–44 and Indigenous children aged 0–4, by remoteness, 2011

Spatial distribution of hospitals with a birthing unit

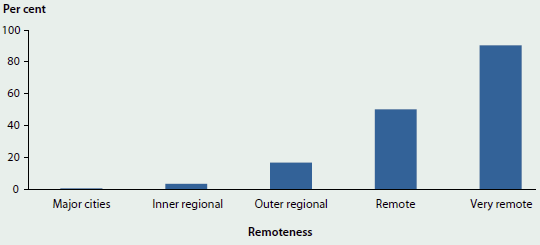

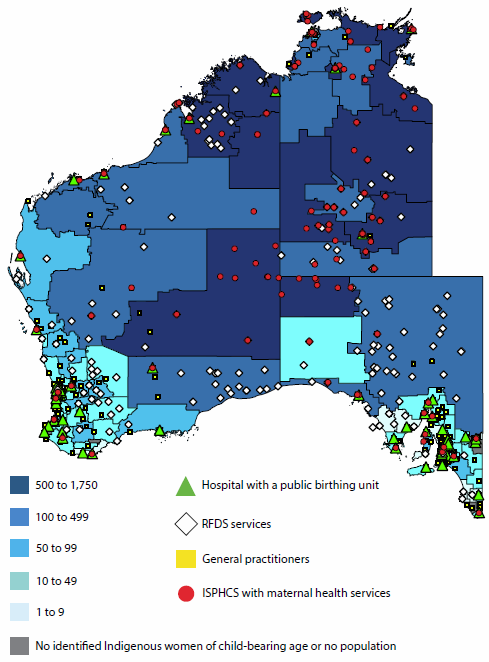

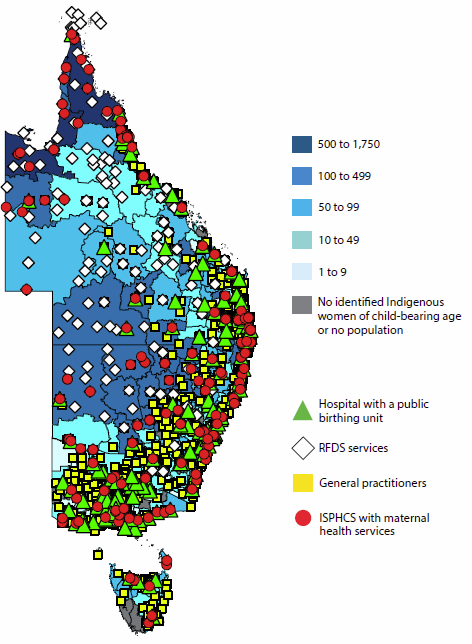

Access to high quality, evidence-based and culturally competent maternity care close to where women live is one of the goals of the National Maternity Services Plan (AHMAC 2011), and is expected to help close the demonstrated gap in infant and child health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous babies and children.

The geographic supply and accessibility of hospitals offering birthing services is a critical issue for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and families, and for residents of rural and remote areas in general. In rural and remote areas where no birthing facilities are available, women assessed at normal risk of poor outcomes are often required to relocate to an urban or regional hospital location at 36–38 weeks of pregnancy. Those at higher risk—because of prior pre-term delivery, stillbirth, or baby born of low birthweight; maternal age; obesity; or because of identified medical conditions—may need to spend weeks away from home and family. Available data show that Indigenous mothers are 1.6 times as likely to be obese as non-Indigenous mothers and are also more likely to have higher rates of pre-existing hypertension and pre-existing diabetes (AIHW 2015a).