Primary and secondary schooling

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Primary and secondary schooling, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Primary and secondary schooling. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/primary-and-secondary-schooling

MLA

Primary and secondary schooling. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/primary-and-secondary-schooling

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Primary and secondary schooling [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 26]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/primary-and-secondary-schooling

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Primary and secondary schooling, viewed 26 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/primary-and-secondary-schooling

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

On this page

Higher levels of education are associated with increased likelihood of being employed, being in good health and reporting higher life satisfaction (ABS 2022; OECD 2016). In Australia, children must attend school until they complete Year 10. After year 10, people are required to participate in education, training, or employment until they are 17 years old. In Australia, completing Year 12 or an equivalent qualification is now considered to be an important milestone in the transition to adulthood (Liu and Nguyen 2011). Those who have completed Year 12 are more likely to continue with further education or training and have a more successful transition into the workforce (ABS 2011; Deloitte 2012; Ryan 2011).

This page presents national statistics for an overview of Australia’s performance in primary and secondary education.

School achievement

School student achievement refers to the extent to which a student has attained their short- or long-term educational goals. Ongoing assessment of student achievement can be used to help teachers monitor student learning, identify gaps in a student’s knowledge, and target teaching to each student’s needs.

States and territories require schools to measure, monitor, and report on students’ school achievement across the school’s curriculum. However, the nature and format of this reporting is often specific to schools or jurisdictions. School-reported student achievement data is not collated nationally. This section reports on national sources of data on student achievement. These sources tend to focus on literacy and numeracy measured through standardised tests.

NAPLAN

The National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) is an annual assessment of students in years 3, 5, 7 and 9. NAPLAN assesses the following:

- reading

- writing

- language conventions (spelling, grammar and punctuation)

- numeracy (ACARA 2022b).

NAPLAN results provide data to assess achievement against the national minimum standard and mean score (see glossary). NAPLAN mean scores generally range from 0–1,000 points, with higher scores indicating better performance. NAPLAN test results are equated to a scale established in 2008 so that a score of 700 in reading has the same meaning in each year, thus results can be compared with previous years (ACARA 2022b). From 2023 onwards there are changes to the way NAPLAN results are reported (see Changes to NAPLAN in 2023). In 2022, NAPLAN tests were completed by students entirely online for the first time (ACARA 2022b). While results are standardised across years, this change must be taken into account when comparing 2022 results to previous years. No results are available for 2020 as Education ministers made the decision to cancel NAPLAN due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Changes to NAPLAN in 2023

A review of the NAPLAN standardised testing was commissioned in 2019. The review considered whether NAPLAN remains fit-for-purpose and made several recommendations for future versions of the national standardised assessment (McGaw et al 2020). Based on this review, in 2023, the test was held in Term 1 (instead of Term 2) in March. This allows results to be published earlier in the year to inform school programs and will allow teachers to better support students for the year ahead (ACARA 2022a).

In addition, from 2023 onwards, NAPLAN results will be reported against 4 levels of achievement bands, 'Exceeding', 'Strong', 'Developing' and 'Needs additional support' instead of the existing national minimum standard and 10 proficiency bands (DoE 2023). A new NAPLAN time series begins from 2023. Data reported on this page (2008 and 2022) cannot be compared with NAPLAN 2023 results.

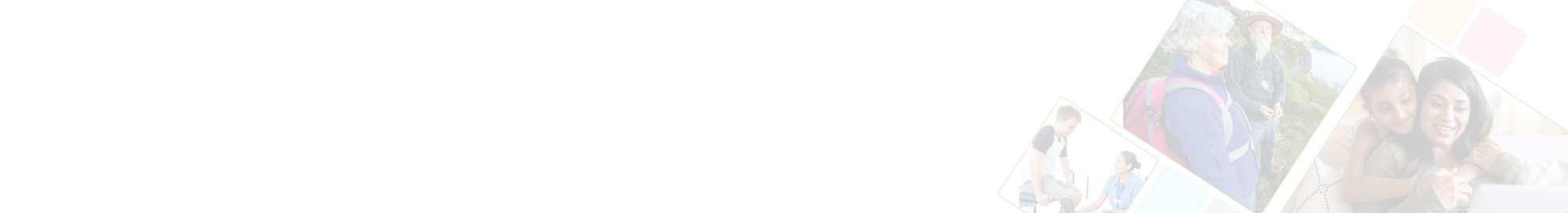

Since its inception, national average achievement in NAPLAN scores have remained stable or modestly improved. In 2022, the average achievement, or national mean score, was above 2008 results for year 3 students in reading, spelling and grammar and for year 5 students in reading, spelling and numeracy. Average achievement in all other domains across years 3, 5, 7 and 9 remained similar or not statistically different from inception (Figure 1).

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) students, NAPLAN average scores since inception have trended upwards with modest improvements across most domains and year levels. For more information see Education of First Nations people.

National mean scores on NAPLAN domains in 2022 did not change substantially from 2021 results.

In 2022:

- Across all assessed year levels, female students attained a higher mean score than males in reading, writing, spelling, and grammar and punctuation. On the numeracy domain, females attained a lower mean score than males.

- Students from Very remote areas scored lowest across all NAPLAN domains when compared with students in other remoteness areas, with scores generally increasing with decreased remoteness.

- By parental education level, children whose parents had attained a bachelor's degree or higher returned the highest mean scores, and mean scores were lower for students whose parents had no post-school education or certificate level post-school education only (ACARA 2022b).

Figure 1: National mean scores across NAPLAN domains by year level, 2008, 2011 and 2022

National mean scores across NAPLAN domains by year level, 2008, 2011 and 2022

This graph shows national mean scores on the NAPLAN domain by year level in 2008, 2011 and 2022. There was a statistically significant increase in mean score for year 3 reading, spelling and grammar & punctuation and year 5 reading, spelling and numeracy in 2022 compared to 2008. Average achievement in all other domains was close to or not statistically different from 2008 results (or 2011 results for writing).

Notes

- Due to changes in the Writing assessment in 2011, the earliest year against which 2022 results on the Writing domain can be compared is 2011.

- The 2022 increase in mean score for year 3 reading, spelling and grammar & punctuation and year 5 reading, spelling and numeracy are statistically significant. All other changes are not statistically significant.

Source: ACARA 2022b.

Using equivalised years of learning (see glossary), gaps in NAPLAN achievement widened as students progressed through school year levels. For example, year 3 students with a parent who had a bachelor’s degree or higher had an additional 1.3 years of learning compared to those who did not. At year 9, the difference in years of learning increased to 3.7 years (PC 2023).

Program for International Student Assessment

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a triennial survey of 15-year-old students around the world. It focuses on the core school subjects of science, reading and mathematics (OECD 2019b). Results can be compared over time from the first year a subject was a major domain on the PISA, 2000 for reading, 2003 for mathematics and 2006 for science.

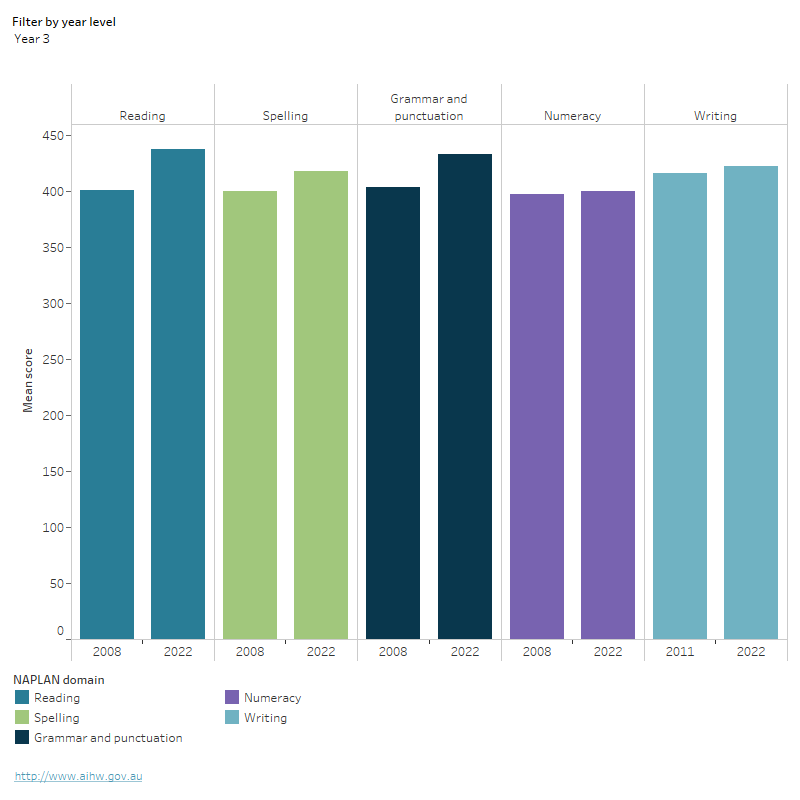

For all three domains, the performance of Australian students was highest at the first year of measurement and have since declined slightly (Figure 2). In 2018, Australian students continued to perform above the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average in science and reading and performed similar to the OECD average in mathematics (OECD 2019a).

The most recent PISA was completed in 2022, results are expected to be available in late 2023.

Figure 2: Mean performance on the PISA, Australia and the OECD, 2000 to 2018

Mean performance on the PISA, Australia and the OECD, 2000 to 2018

This line graph shows the mean performance on the PISA scales, comparing Australia with all OECD countries. Mean performance on the reading literacy scale fluctuated, with an overall decline in Australia (2000: 528, 2018: 503), and as an average of OECD countries (2000: 500, 2018: 487). Mean performance on the Mathematical literacy scale declined in Australia (2000: 533, 2018: 491) and an average of OECD countries (2000: 500, 2018: 489).

Mean performance on the Scientific literacy scale fluctuated, with an overall decline in Australia (2000: 528, 2018: 503) and as an average of OECD countries (2000: 500, 2018: 489).

Notes

- This OECD average includes all OECD member countries for which data were available for the corresponding subject and year. Depending on data availability, the countries contributing to this average might vary by cycle and subject.

- The first full PISA assessment for reading literacy was in 2000, for mathematical literacy in 2003 and for science in 2006. Results for mathematical literacy prior to 2003 and for science prior to 2006 are not comparable with results from later cycles.

Source: OECD 2020.

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study

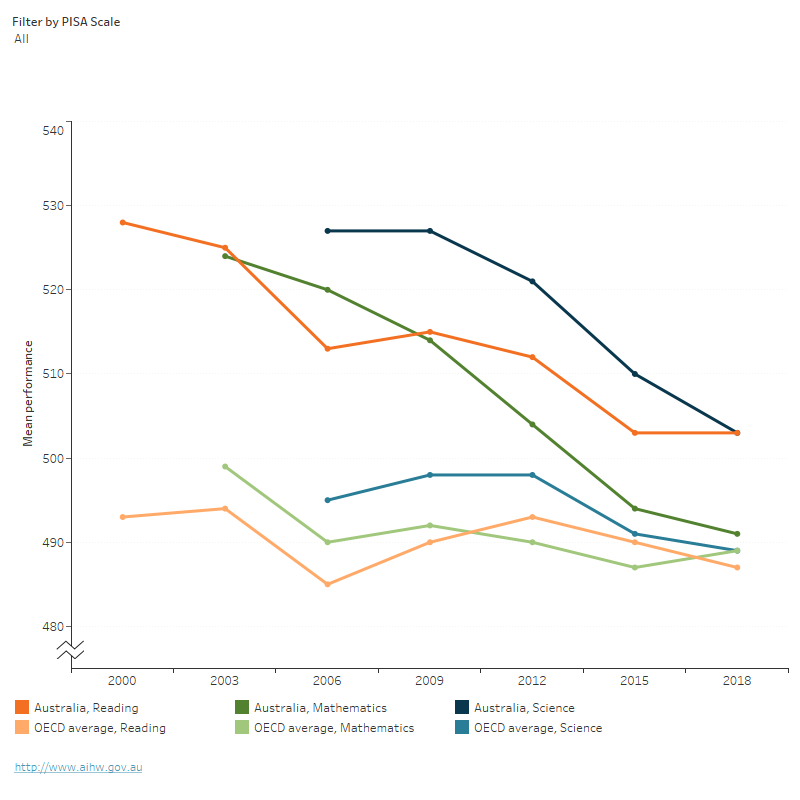

The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) assesses reading literacy in Year 4 students across over 50 countries every five years. The latest available data from the PIRLS comes from the 2021 report. COVID-19 restrictions caused many countries to delay assessing students, meaning the results for some countries are not comparable with others. Australia’s national report presents results from 43 countries that assessed students towards the end of year 4, whether in 2020 as originally scheduled, or in 2021 or 2022. Australia completed the PIRLS assessment in 2021 (Hillman et al. 2023).

- Australia’s average reading score (540) was significantly higher than 28 participating countries, significantly lower than 6 countries, and similar to 8 countries (Figure 3).

- Australia’s average reading score in 2021 was similar to the average reading score in 2016 (544) and an increase since 2011 (527).

- Of the 32 countries that assessed students in year 4 and participated in both PIRLS 2021 and PIRLS 2016, 8 countries had similar scores in 2021 as in 2016, 21 countries experienced a decline and 3 countries had improved scores.

- 80% of Australian year 4 students met or exceeded the PIRLS Intermediate benchmark (the Australian proficient standard), similar to 2016 (81%).

Figure 3: Comparison of mean scores on the PIRLS reading literacy assessment, 2021

Comparison of mean scores on the PIRLS reading literacy assessment, 2021

This horizontal bar chart shows the mean scores on the PIRLS reading literacy assessment across 43 countries. Australia has a mean score of 540. Australia’s mean score was significantly lower than 6 countries and similar to 8 countries. The scores ranged from 288 in South Africa to 567 in Singapore.

Notes

- Countries and educational systems conducted the assessment one year later than originally scheduled are signified with a (1).

- Only countries that completed the PIRLS assessment at a comparable age and school year to Australia are included.

Source: Hillman et al. 2023.

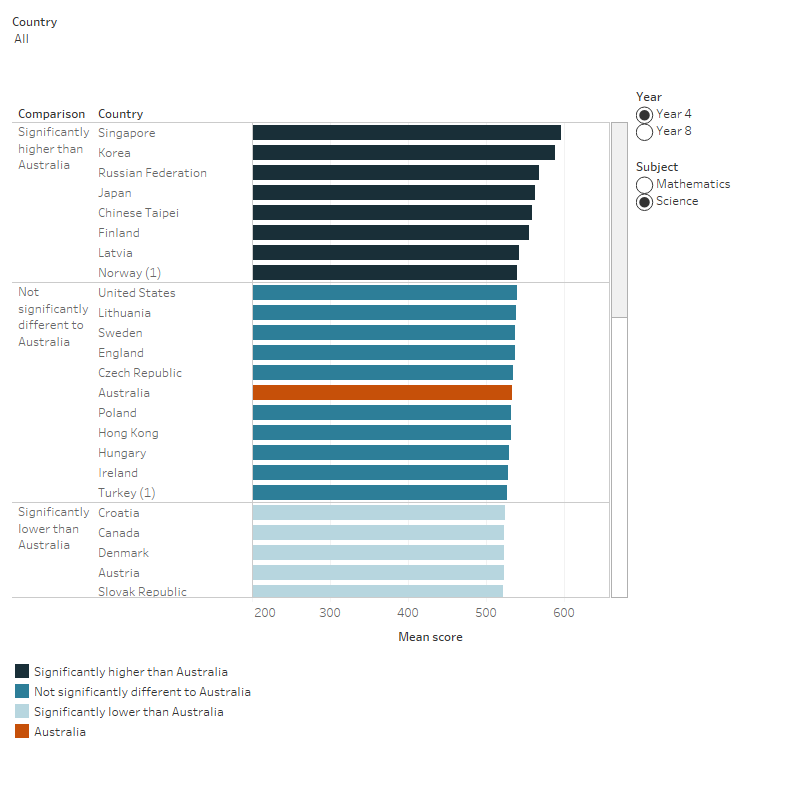

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

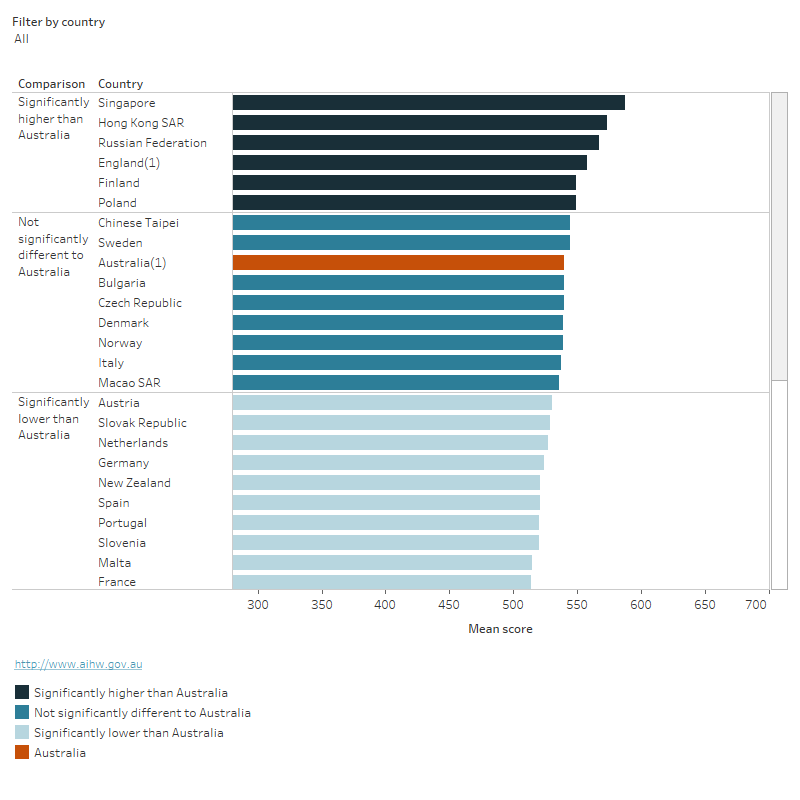

The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) has compared the performance of Year 4 and Year 8 students in mathematics and science internationally every 4 years since 1995. In the 2019 TIMSS report, of the 64 countries that participated, Australia was outperformed by 22 countries in Year 4 mathematics, 6 countries in Year 8 mathematics, 8 countries in Year 4 science, and 6 countries in Year 8 science (Figure 4). The next TIMSS is due to be conducted in 2023.

Figure 4: Comparison of mean scores in the International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), by year level and subject, 2019

This horizontal bar chart shows the mean scores in the International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) across 64 countries. Australia had a mean score of 516 in Year 4 mathematics, 517 in Year 8 mathematics, 533 in Year 4 science and 528 in Year 8 science. Australia was outperformed by 22 countries in Year 4 mathematics, 6 countries in Year 8 mathematics, 8 countries in Year 4 science, and 6 countries in Year 8 science.

Notes

- TIMSS assessment in countries marked with a (1) were undertaken by year 5 students instead of year 4 students.

- TIMSS assessment in countries marked with a (2) undertaken by year 9 students instead of year 8 students.

- Whether a country is categorised as significantly or not significantly different to Australia is dependent on both the mean score and the score distribution in each country. Therefore, some countries with the same mean score may be in a different category of whether they are significantly different or not significantly different from Australia.

Source: Thomson et al. 2020.

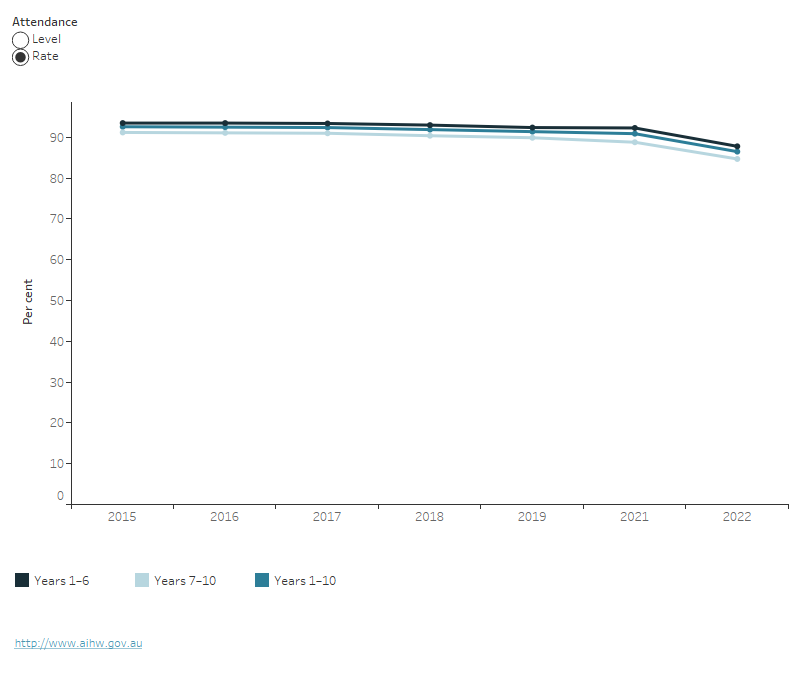

School attendance

Attendance is an indicator of a child’s participation in school. Each day of attendance in school contributes towards a child’s learning and there does not appear to be a 'safe' threshold for which school absences do not have an impact (Hancock et al. 2013).

Student attendance rates refer to the number of actual full-time equivalent days attended by full-time students as a percentage of the total number of possible school days over the period (see glossary). School attendance level refers to the percentage of students who attended school greater than 90% of the time.

In 2022, student attendance rates were:

- 88% for all students in years 1–6 and 85% for all students in years 7–10, this is a decrease since 2015 (94% and 91% respectively) (Figure 5). Some of the decrease may be due to COVID-19 from 2020 onwards and flooding events in 2022

- lower in later year levels (83% in Year 10) than in earlier year levels (87% in Year 7)

- higher in non-government schools (88%) than government schools (86%) for years 1–10

- lower for First Nations children than for non-Indigenous children in years 1–10 (75% and 87% respectively). Between 2015 and 2022, attendance rates declined for both First Nations children (84% in 2015 to 75% in 2022) and for non-Indigenous children (93% in 2015 to 87% in 2022) (see Education of First Nations people)

- higher in Major cities (88%) compared with Inner regional (85%), Outer regional (84%), Remote (79%), and Very remote (63%) areas for years 1–10 (ACARA 2023b).

In 2022, student attendance levels were 53% for all students in years 1–6 and 45% for students in years 7–10. This is a decrease since 2015 (from 80% and 74% respectively) (ACARA 2023b). The larger decrease in attendance level from 2015 to 2022 compared to attendance rate may be due to the high cut off for measuring attendance level (90%). An attendance rate of 88% and an attendance level of 53% suggests that many students may be attending at rates just below the cut-off level.

Figure 5: Rate and level of school attendance by year level group, 2015 to 2022

Rate and level of school attendance by year level group, 2016 to 2022

This line graph shows the attendance rate and level between 2015 and 2022 for children in years 1-6, years 7-12 and years 1-10. All groups show a decrease in attendance between 2015 and 2022, with a substantial drop in 2022.

Notes

- Attendance rates are the number of actual full-time equivalent student-days attended by full-time students in Years 1 to 10 as a percentage of the total number of possible student-days attended over the period.

- Attendance level is the percentage of students who attended school more than 90% of the time.

- From 2018, attendance data for NSW government schools has been collected and compiled consistently with the National Standards. Prior to 2018, NSW government schools data were not collected on a comparable basis with other jurisdictions. From 2015 to 2017, for government school attendance rates for NSW, comparisons across jurisdictions and with 2018 for should be made with caution.

- ACT government school data for 2018 and 2019 are derived from a school administration system in the process of implementation. Care should be taken when comparing these data with previous years and from other jurisdictions.

- School attendance in Semester 1 2022 declined due to the impact of the COVID-19 Omicron variant and high influenza season outbreaks and floods in certain regions experienced across Australia at that time.

Source: ACARA 2023b.

School retention

The apparent retention rate to year 12 is an estimate of the percentage of students who stay enrolled full time in secondary education from the start of secondary school (year 7 or 8, depending on the state or territory) to year 12 (see glossary).

In 2022, the apparent retention rate to year 12 was:

- 81%, an increase from 79% in 2011, but a decrease since a peak of 85% in 2017

- higher for females (85%) than males (76%)

- higher for non-Indigenous people (82%) than First Nations people (57%). The school retention rate for First Nations people has increased 8.2 percentage points since 2011 while the retention rate for non-Indigenous people has increased 1.3 percentage points (ABS 2023).

School attainment

Year 12 attainment

The attainment rate is the proportion of all estimated year 12 students who meet the requirements of a year 12 or equivalent qualification (see glossary) (SCRGSP 2023). After decreasing from 79% in 2018 to 72% in 2019, the year 12 attainment rate has increased back to 79% in 2021 (SCRGSP 2023). The attainment rate in 2019 may have been affected by a half cohort in Queensland (ACARA 2023a). In 2021, attainment rates increased with increasing socioeconomic position (see glossary), from 74% in low socioeconomic areas to 85% in high socioeconomic areas. Attainment rates were substantially lower in Very remote areas (51%) compared with other areas (82% in Major cities, 72% in Inner and outer regional areas and 73% Remote areas) (SCRGSP 2023).

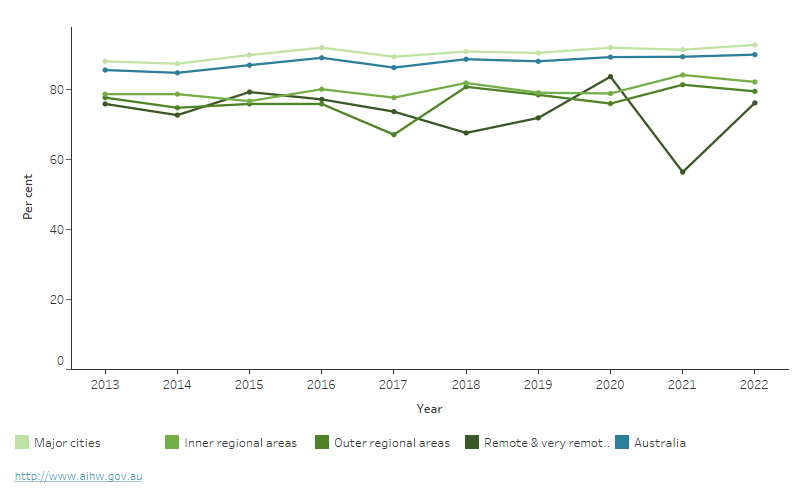

In 2022, 4 in 5 (80%) people aged 15–64 had attained year 12 or equivalent or a non-school qualification at certificate III level or above, an increase of 7 percentage points since 2013 (73%) (ABS 2022).

In 2022, of people aged 20–24:

- 90% had attained a qualification at year 12 or certificate III level or above

- women (93%) were more likely than men (88%) to have completed year 12 or a certificate III or above, consistent with previous years

- people living in Major cities (93%) were more likely than those living in other remoteness areas to have completed year 12 or a certificate III or above (ABS 2022).

Among people aged 20–24, the attainment rate of year 12 or certificate III or above increased overall between 2013 and 2022, from 86% to 90%. The attainment rate fluctuated more for people in regional and remote areas than for people living in Major cities, but in general increased with decreasing remoteness area (Figure 6).

Labour market participation rates are higher for those with higher levels of education attainment. In 2020, the participation rate for those with a highest level of educational attainment of year 12 or equivalent was 71%, compared with 62% for those who had completed year 11 and 51% for those who had completed year 10 or below (National Skills Commission 2021). For more information see Higher education, vocational education and training and Employment and unemployment.

Figure 6: Proportion of people aged 20–24 with year 12 or equivalent, or non-school qualification at certificate III level or above, by remoteness area, 2013 to 2022

Proportion of people aged 20–24 with year 12 or equivalent, or non-school qualification at certificate III level or above, by remoteness area, 2013 to 2022

This horizontal bar chart shows that the percentage of people aged 20–24 with year 12 or equivalent, or non-school qualification at Certificate III level or above, varies by remoteness area, with people living in less remote areas generally having higher rates of year 12 attainment.

Note: Year12/Certificate III education attainment for Remote and Very remote areas should be interpreted with caution due to a high relative standard of error (25% to 50%) (ABS 2022).

Source: ABS 2022.

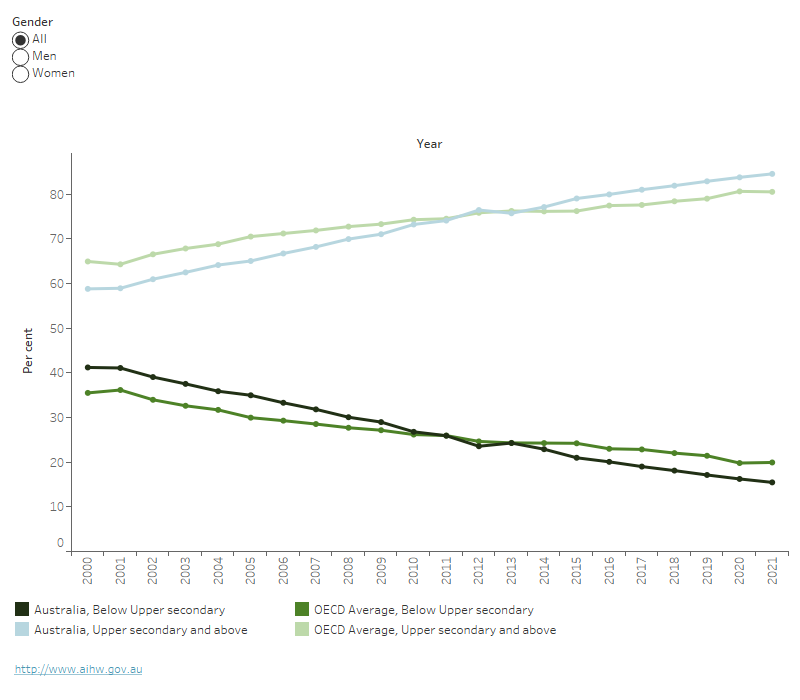

Highest level of education

The OECD publishes annual estimates of adult education level for each member country using the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) system. This is defined as the highest education level of the 25–64 year old population. Categories of highest education level include below upper secondary and upper secondary and above. While it varies between country, lower secondary education includes provision of basic education, upper secondary is considered to be the final 3 years of secondary school (in Australia years 10–12), and levels above this are classified as tertiary education.

Since 2000, the percentage of people aged 25–64 years in Australia with upper secondary or above has increased at a faster rate than the OECD average. The percentage of adults with an upper secondary or above education level in Australia has increased from 59% in 2000 to 85% in 2021. In comparison, the OECD average has increased from 65% in 2000 to 81% in 2021 (Figure 7). Meanwhile, the percentage of Australian adults whose highest education is below upper secondary has decreased substantially from 41% in 2000 to 15% in 2021 (OECD 2023).

The increase in upper secondary and above education between 2000 and 2021 in Australia has been greater in women (33 percentage point increase) than men (19 percentage point increase) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Proportion of adult population aged 25–64 years old, Australia and OECD average, by highest level of education completed and gender, 2000 to 2021

Proportion of adult population aged 25–64 years old, Australia and OECD average, by highest level of education completed and gender, 2000 to 2021

This line graph shows the percentage of adult population whose highest level of education is either below upper secondary or upper secondary and above. Between 2000 and 2021, there was an increase in the percentage of those with upper secondary and above education and a decrease in below upper secondary education for both Australia and the OECD average.

Notes

- Indicator is measured as a percentage of the same age population.

- The category 'Upper Secondary and Above' includes adults who have either upper secondary or tertiary as their highest level of education completed.

- Data for men and women are only available for the category 'Upper secondary and above'.

Source: OECD 2023.

The impact of COVID-19

School students and teachers across Australia were severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. It disrupted teaching and learning across all states and territories. However, each state and territory experienced and responded to the pandemic differently. Some were able to maintain a capacity for classroom learning, while others had to quickly adapt to an entirely online learning environment for an extended period of time, continuing into 2021 (Sullivan et al. 2021).

Due to the impact of COVID-19, school attendance data, usually published on an annual basis, were not available for 2020. Similarly, the NAPLAN tests scheduled to take place in 2020 were cancelled.

Despite the effects of the pandemic, NAPLAN results for 2021 and 2022 were similar to 2019 results for the population as a whole (ACARA 2021, 2022b). One report found that the COVID-19 pandemic had a smaller impact on learning delays in Australian students than other countries. The estimated learning delay for Australian students was less than two months while students in other countries may be more than a year behind (McKinsey and Company 2022). However, the impact of COVID-19 on learning and teaching is yet to be fully understood and is likely to be a focus of research well into the future.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information, see:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS):

- Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) The National Assessment Program

- OECD Programme for International Student Assessment

- Australian Council for Education Research (ACER) Progress in International Reading Literacy Study

- ACER Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2011) Year 12 attainment, Australian social trends March 2011, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 8 June 2023.

ABS (2022) Education and Work, Australia, May 2022, ABS Website, accessed 12 January 2023.

ABS (2023) Schools 2022, ABS Website, accessed 16 March 2023.

ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) (2021) National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy Achievement in Reading, Writing, Language Conventions and Numeracy: National Report for 2021, ACARA, accessed 7 December 2022.

ACARA (2022a) NAP improvements announced: Improvements to NAPLAN from 2023, ACARA, accessed 13 January 2023.

ACARA (2022b) National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy National Report for 2022, ACARA, accessed 7 December 2022.

ACARA (2023a) National report on schooling data portal, year 12 certification rates [data set], ACARA, accessed 5 May 2023.

ACARA (2023b) National report on schooling data portal, school attendance [data set], ACARA, accessed 5 May 2023.

Deloitte Access Economics (2012) Youth Transitions Evidence Base: 2012 update, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, Australian Government, accessed 17 February 2023.

DET (Department of Education and Training) (2018) National School Reform Agreement, Department of Education and Training, Australian Government, accessed 13 January 2023.

DoE (Department of Education) (2023) Education Ministers Meeting Communique – 10 February 2023, Department of Education, Australian Government, accessed 16 February 2023.

Hancock KJ, Shepherd CCJ, Lawrence D and Zubrick SR (2013) Student attendance and educational outcomes: Every day counts [PDF 8.1MB] , Report to the Australian Government Department of Educations, Employment and Workplace Relations, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, University of Western Australia, accessed 8 June 2023.

Liu S and Nguyen N (2011) Longitudinal surveys of Australian youth, briefing paper 25: successful youth transitions, National Centre for Vocational Education Research Ltd (NCVER), accessed 8 June 2023.

McGaw B, Louden W and Wyatt-Smith C (2020) NAPLAN Review final report, Department of Education, New South Wales Government, Department of Education, Queensland Government, Department of Education and Training, Victorian Government, and Australian Capital Territory Government, accessed 8 June 2023.

McKinsey and Company (2022) How COVID-19 caused a global learning crisis, McKinsey and Company, accessed 5 May 2023.

National Skills Commission (2021) Australian Jobs 2021, National Skills Commission, Australian Government, accessed 2 May 2023.

NIAA (National Indigenous Australians Agency) (2022) Commonwealth Closing the Gap Annual Report 2022, NIAA, Australian Government, accessed 13 January 2023.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2016) How are health and life satisfaction related to education? Education Indicators in Focus no. 47, OECD, accessed 13 January 2023.

OECD (2019a) Country Note; Australia, OECD, accessed 13 January 2023.

OECD (2019b) PISA 2018 Results (Volume I) What students know and can do, OECD, accessed 13 January 2023.

OECD (2020) PISA Data Explorer [data set], OECD website, accessed 7 June 2023.

OECD (2023) Adult education level (indicator), OECD website, accessed 20 March 2023

PC (Productivity Commission) (2023) Review of the National School Reform Agreement: Study report, PC, Australian Government, accessed 2 February 2023.

Ryan C (2011) Year 12 completion and youth transitions, NCVER, accessed 17 February 2023.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) (2023) Report on Government Services 2023, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 16 March 2023.

Sullivan K, Yew A and Doan M (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on teaching in Australia, AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership), accessed 8 June 2023.

Hillman K, O’Grady E, Rodrigues S, Schmid M and Thomson S (2023) Progress in International Reading Literacy Study: Australia’s results from PIRLS 2021, Australian Council for Educational Research, accessed 31 May 2023.

Thomson S, Wernert N, O’Grady E and Rodrigues S (2020) TIMSS 2019: Volume 1: Student performance, Australian Council for Educational Research, accessed 13 January 2023.