Back problems

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Back problems, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Back problems. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/back-problems

MLA

Back problems. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 14 December 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/back-problems

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Back problems [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 24]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/back-problems

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Back problems, viewed 24 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/back-problems

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Page highlights

- ‘Back problems’ describes a range of conditions related to the bones, joints, connective tissue, muscles and nerves of the back.

- An estimated 4.0 million (16%) people in Australia reported having back problems in 2017–18.

- People with back problems had over double the rates of reporting ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health (26%), ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain (50%), and ‘high’ to ‘very high’ psychological distress (22%), compared with those without the condition.

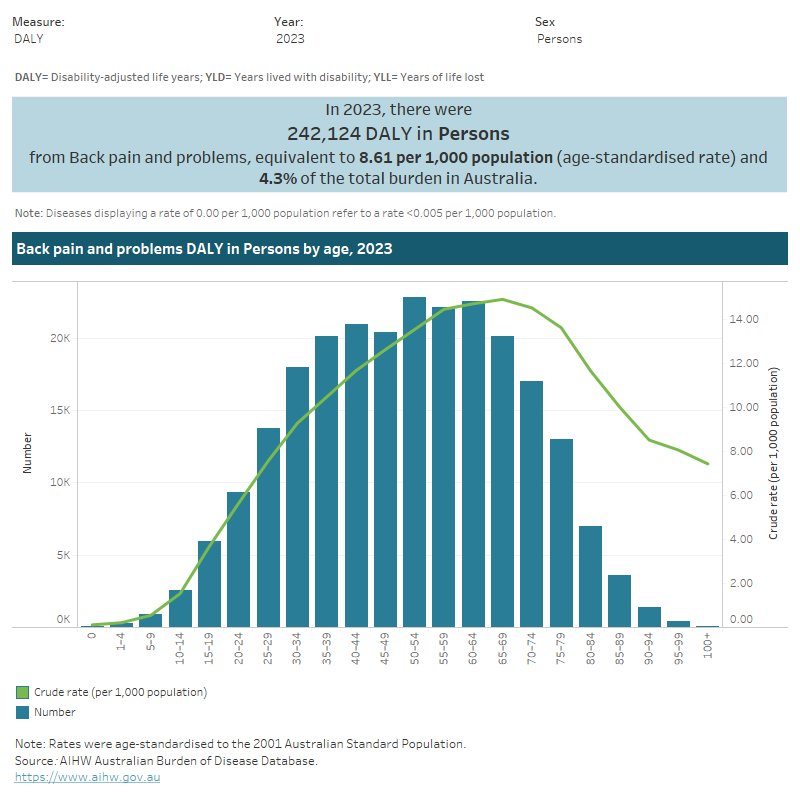

- Back problems were the third leading cause of disease burden overall, accounting for 4.3% of Australia’s total disease burden in 2023.

- In 2020–21, an estimated $3.4 billion was spent on the treatment and management of back problems, representing 2.2% of total health system expenditure and 23% of expenditure for all musculoskeletal conditions.

- Back problems contributed to 1,024 deaths or 4.0 deaths per 100,000 population in 2021 (0.6% of all deaths).

Treatment and management of back problems

- In 2021–22, there were 177,000 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of back problems (690 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).

Comorbidities of back problems

- 74% of people with back problems reported also having one or more other chronic conditions – the top 3 comorbidities were arthritis (48%), mental and behavioural conditions (34%), and asthma (17%).

What are back problems?

'Back problems’ describes a range of conditions related to the bones, joints, connective tissue, muscles and nerves of the back. These conditions can affect the neck (cervical spine), upper back (thoracic spine) and lower back (lumbar spine) as well as the sacrum and tailbone (coccyx) (Figure 1). Back problems are a significant cause of disability and lost productivity.

Examples of back problems include:

- Back or spine pain (such as lower back pain, and sciatica)

- vertebrae and disc disorders (such as narrowing of the spinal canal, and disc degeneration)

- deforming disorders (such as scoliosis).

Figure 1: Lateral view of spine

How common are back problems?

An estimated 4.0 million (16%) people in Australia reported having back problems, according to the 2017–18 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS) (ABS 2019a). Note that this prevalence estimate includes sciatica, disc disorders, curvature of the spine, and back pain/problems not elsewhere classified. Furthermore, some back problems associated with another condition, such as osteoporosis, are not included.

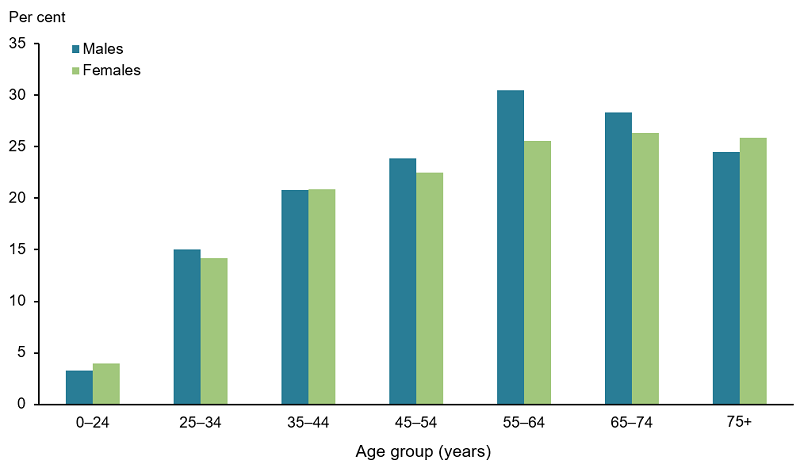

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, back problem prevalence increased with age and was similar for males and females (Figure 2). Prevalence also changed little by Indigenous status, remoteness or socioeconomic areas (see Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3).

Figure 2: Prevalence of back problems, by age and sex, 2017–18

Note: Refers to people who self-reported having back problems (current and long term).

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 1.1).

Impact of back problems

Back problems often lead to poorer quality of life, psychological distress, bodily pain, and disability.

How do back problems affect quality of life?

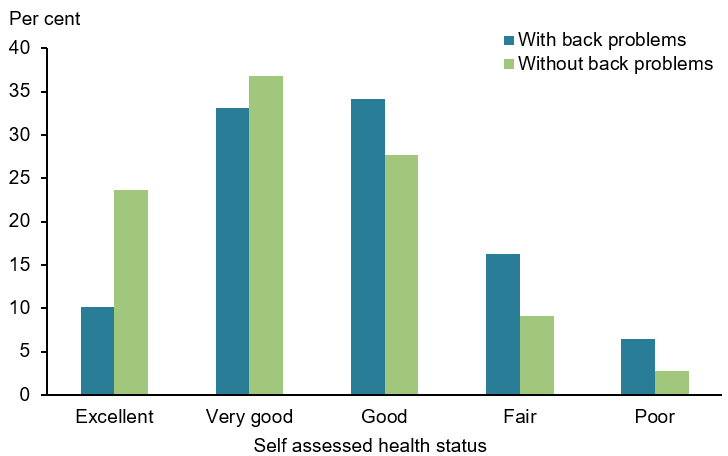

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, after adjusting for age, people with back problems:

- aged 15 and over were 1.9 times as likely to report ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health compared with those without back problems (23% and 12%, respectively) (Figure 3)

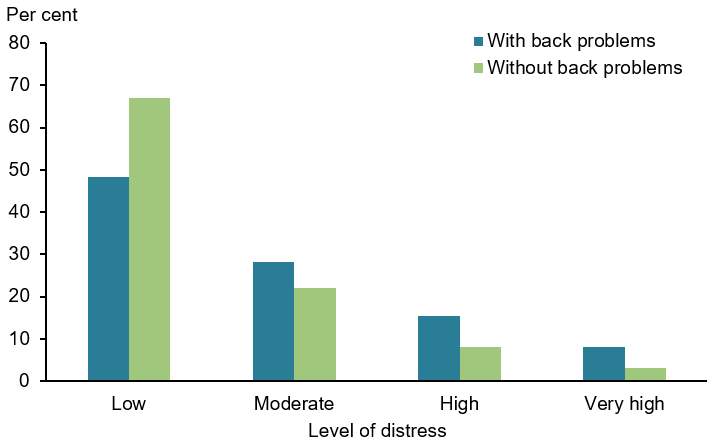

- aged 18 and over were 2.1 times as likely to report experiencing ‘high’ to ‘very high’ levels of psychological distress compared with those without the condition (24% and 11%, respectively) (Figure 4)

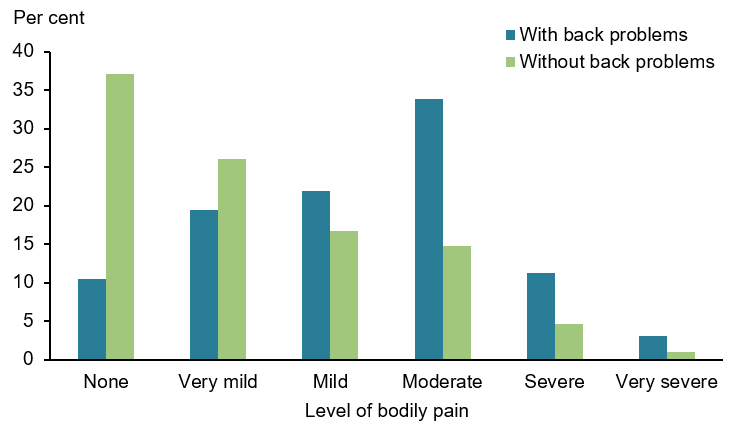

- aged 18 and over were 2.4 times as likely to experience ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain compared with those without the condition (48% and 20%, respectively) (Figure 5)

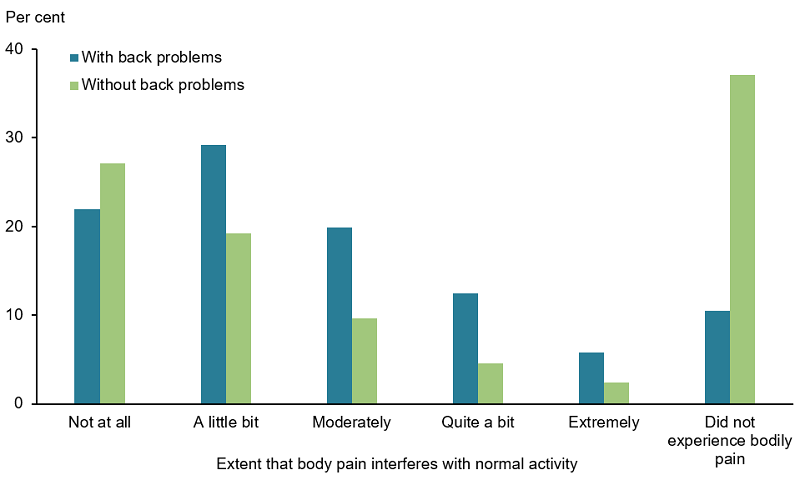

- were 2.3 times as likely to report that bodily pain interfered with their daily activities at least 'moderately' compared with people without back problems (38% and 17% respectively) (Figure 6)

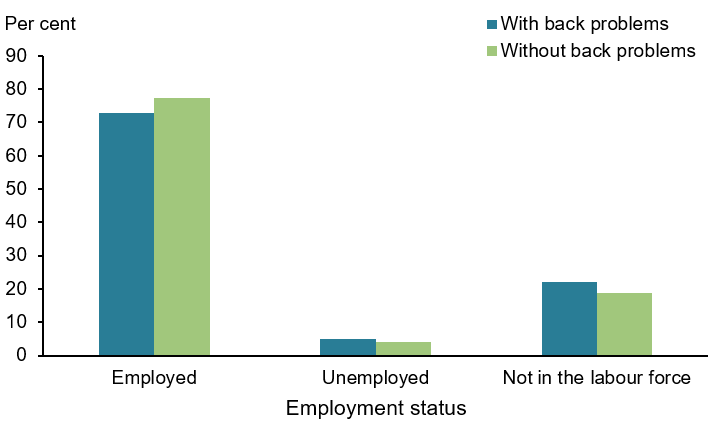

- aged 15–64 were less likely to be employed compared with people without back problems (73% and 77%, respectively) and more likely to not be in the labour force (22% compared with 19%) (Figure 7)

- were almost as likely to be unemployed as people without back problems (5% and 4% respectively) (Figure 7).

Figure 3: Self-assessed health of people aged 15 and over with and without back problems, 2017–18

Note: Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 2.1).

Figure 4: Psychological distress experienced by people aged 18 and over with and without back problems, 2017–18

Notes:

- Psychological distress is measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), which involves 10 questions about negative emotional states experienced in the previous 4 weeks. The scores are grouped into Low: K10 score 10–15, Moderate: 16–21, High: 22–29, Very high: 30–50.

- Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 2.2).

Figure 5: Pain experienced by people aged 18 and over with and without back problems, 2017–18

Notes:

- Bodily pain experienced in the 4 weeks prior to interview.

- Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 2.3).

Figure 6: Extent that bodily pain interferes in daily activities in people with and without back problems, 2017–18

Note: Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 2.4).

Figure 7: Workforce participation of people aged 15–64 with and without back problems, 2017–18

Note: Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 2.5).

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

In 2023, back problems were the third leading cause of burden and accounted for 4.3% of total burden (DALY); 7.9% of non-fatal burden (YLD), and less than 1% of fatal burden (YLL). Within the musculoskeletal condition disease group, back problems accounted for 34% of total burden (DALY); 34% of non-fatal burden (YLD); and 6.0% of fatal burden (YLL) (AIHW 2023a).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023, the rate of burden from back problems increased with age and was similar for males and females (Figurev8). Back problems were the leading cause of burden for people aged 35–54.

Figure 8: Burden of disease due to back problems by sex, age and year

This figure shows that both fatal and non-fatal burden were similar for males and females in 2023.

Trends over time

Between 2003 and 2023, the age standardised rate of burden from back problems remained stable (8.0 to 8.6 DALY per 1,000 population) (Figure 8). For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023.

Variation between population groups

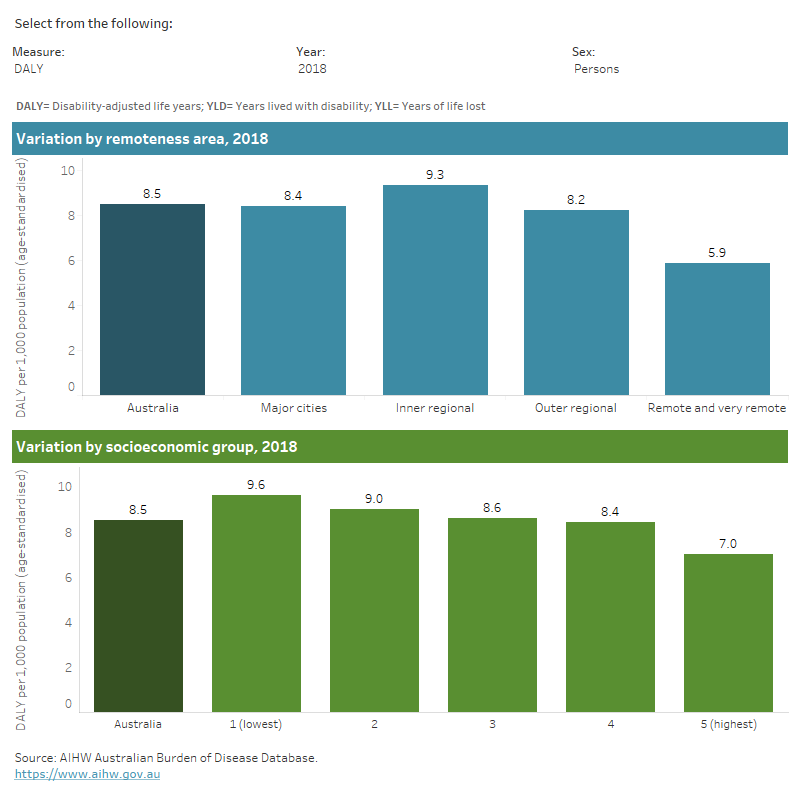

In 2018, the age standardised rate of burden from back problems:

- was highest in Inner regional areas compared with those in Remote and very remote areas (9.3 and 5.9 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- increased with increasing levels of disadvantage – for example, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) were 1.4 times as likely to have back problems compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (9.6 and 7.0 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 9) (AIHW 2021).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden.

Figure 9: Burden of disease due to back problems for remoteness area and socioeconomic group by sex and year

This figure shows the rate of non-fatal burden from back problems was highest for people living in inner regional areas in 2018.

Health system expenditure

In 2020–21, an estimated $3.4 billion of expenditure in the Australian health system was for back problems, representing 2.2% of total health expenditure and 23% of expenditure for all musculoskeletal conditions (AIHW 2023b).

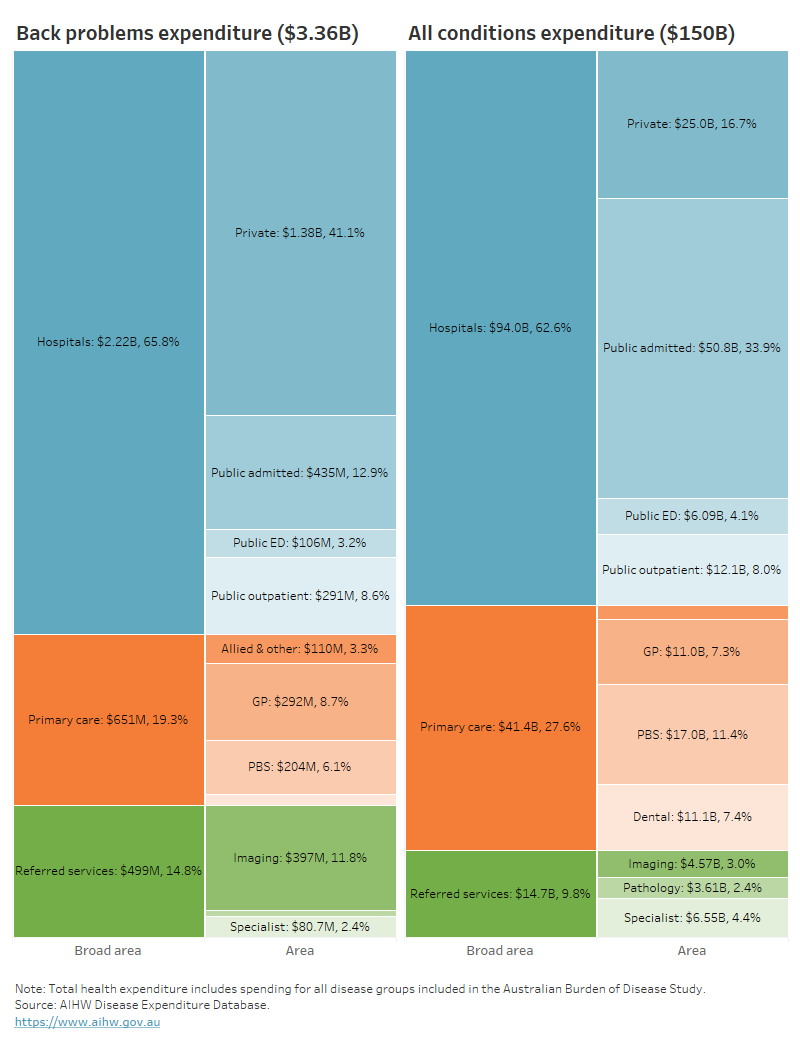

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–21:

- hospital services represented 66% ($2.2 billion) of back problems expenditure which was to similar the hospital proportion for all disease groups (63%). However, the private hospital proportion of back problems expenditure was more than double the proportion for all disease groups (41% compared with 17%)

- primary care accounted for 19% ($650.5 million) of back problems spending, which was less than the proportion for all disease groups (28%)

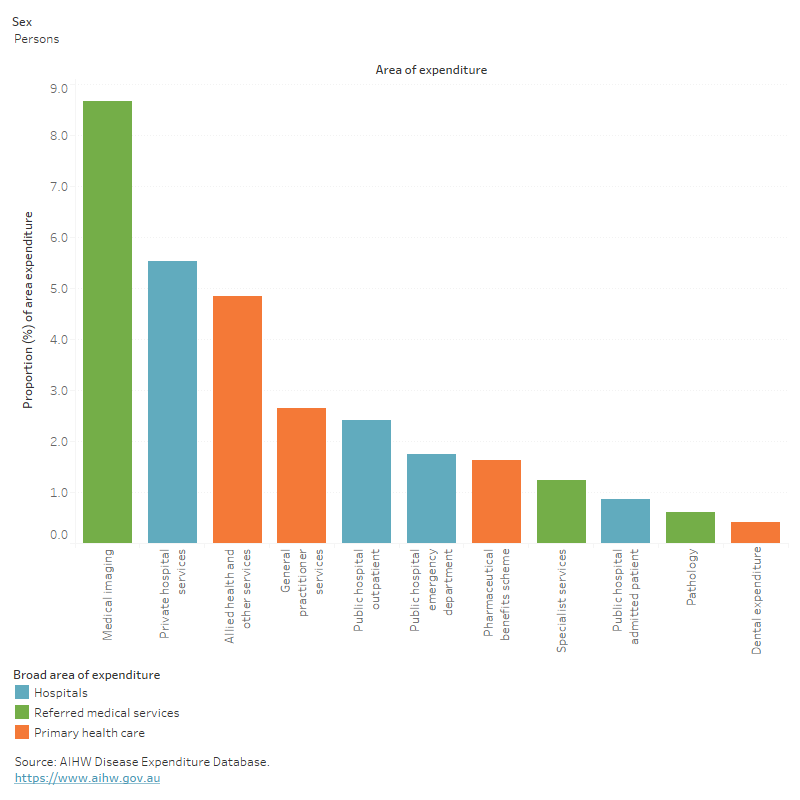

- referred medical services represented 15% ($499.3 million) of back problems expenditure 1.5 times more than the proportion for all disease groups (10%). The medical imaging proportion of back problems expenditure was especially large in comparison to the average, at 3.9 times the proportion for all disease groups (12% compared with 3%) (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Back problems expenditure attributed to each area of the health system, with comparison to all disease groups, 2020–21

This figure shows that the public admitted patients’ hospital proportion of back problems expenditure was $$435 million (12.9%) in 2020-21.

In 2020–21, back problems accounted for:

- 8.7% ($396.5 million) of all medical imaging expenditure – ranking third of all diseases/ conditions

- 5.5% ($1.4 billion) of all private hospital service expenditure – ranking third of all diseases/ conditions (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Proportion of expenditure attributed to back problems, for each area of the health system, 2020–21

This figure shows that 4.8% of back problem expenditure was attributed to allied health and other services.

Who is the money spent on?

In 2020–21:

- the age distribution of spending on back problems reflected the prevalence distribution of the condition, with most spending being for older age groups (76% for people aged 45 and over)

- more back problems expenditure was attributed to females than males ($1.8 billion and $1.5 billion, respectively with a remaining $46.3 million (1.4%) unattributed to any sex.

For more information, see Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21.

In 2018–19, it was estimated that back problems expenditure per case was:

- 13% as high for females compared with males ($860 and $760 per case, respectively)

- 32% lower than musculoskeletal conditions as a group ($820 and $1200 per case, respectively) (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors.

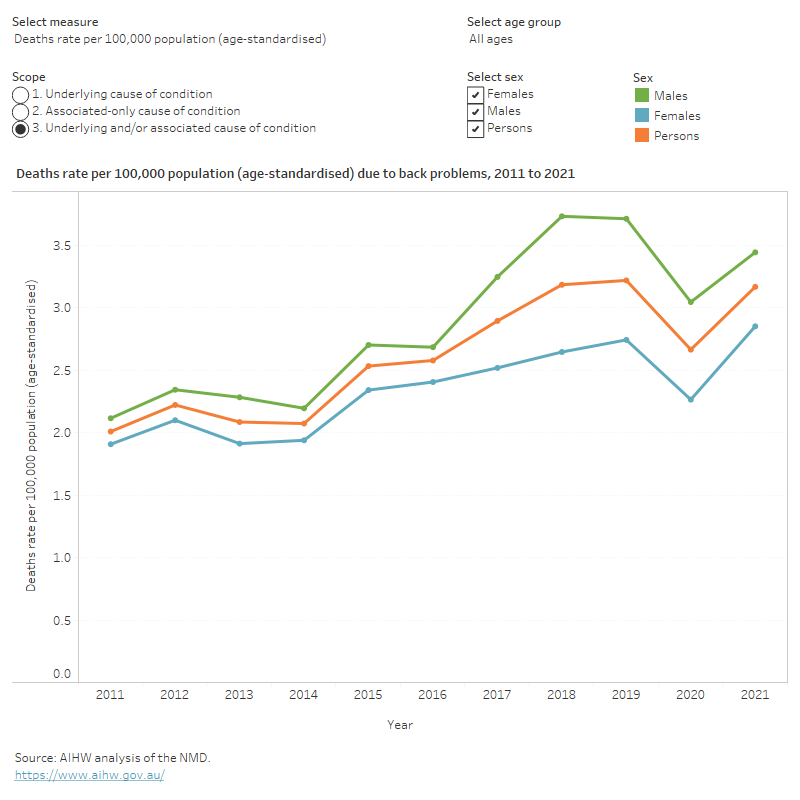

How many deaths were associated with back problems?

Back problems was recorded as an underlying and/or associated cause for 1,024 deaths or 4.0 deaths per 100,000 population in Australia in 2021, representing 0.6% of all deaths and 11% of all musculoskeletal deaths.

Back problems were the underlying cause for 111 deaths (11% of all back problem deaths) and an associated cause only, for 913 deaths (89% of all back problem deaths).

Age standardised mortality rates for back problems (as the underlying and/or associated cause) between 2011 and 2021:

- trended up from 2.0 to 3.2 per 100,000 population

- were 1.1 to 1.4 times as high among males compared with females (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Trends over time for back problems mortality, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that from 2011 to 2021, the death rate due to back problems increased from 2.4 to 4.0 deaths per 100,000 population (underlying and/or associated cause).

Variation between population groups

In 2021, after adjusting for differences in age structure, back problem mortality rates (underlying and/or associated cause) were 1.8 times as high for people living in:

- Remote and very remote areas, compared with people living in Major cities (5.4 and 3.0 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively)

- the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage), compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (3.8 and 2.1 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively).

For more information on mortality data, see the Chronic musculoskeletal condition mortality data tables 2023.

Treatment and management of back problems

Pain is the main symptom of most back problems and treatment can be complex. This can be further complicated by comorbid conditions.

The most recent Australian clinical practice guidelines for management of non-specific low back pain encourages reassurance, self-management and physical therapy as first line care, supplemented by non-pharmacological therapies such as heat, massage, acupuncture and mindfulness where appropriate (Almeida et al. 2018).

Medications are discouraged except where first and second-line non-pharmacological interventions are unsuccessful, and when they are prescribed, the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time possible is advised (Almeida et al. 2018).

For more information on how to manage back pain see MyBackPain.org.au.

General practitioners and back pain treatment

General practitioners (GPs) are usually the first point of contact with the health care system for people with back problems. Back problems are among the most commonly managed conditions in general practice (Almeida et al. 2018).

Until 2017, the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) survey was the most detailed source of data about general practice activity in Australia (Britt et al. 2016). Between 2006–07 and 2015–16, the number of GP-patient encounters for management of back problems increased from 2.6 to 3.1 of every 100 GP-patient encounters for chronic conditions.

It is worth noting that there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection to monitor provision of care by GPs. See General practice, allied health and other primary care services.

Hospitalisations for back problems

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that in 2021–22, there were 262,000 hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of back problems, representing 2.3% of all hospitalisations.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of back problems, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of back problems.

In 2021–22:

- there were 177,000 hospitalisations for back problems, representing 1.5% of all hospitalisations in Australia, and 690 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- back problems accounted for 536,000 bed days, representing 1.7% of all bed days

- 45% of back problems hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 5.5 days (Figure 13).

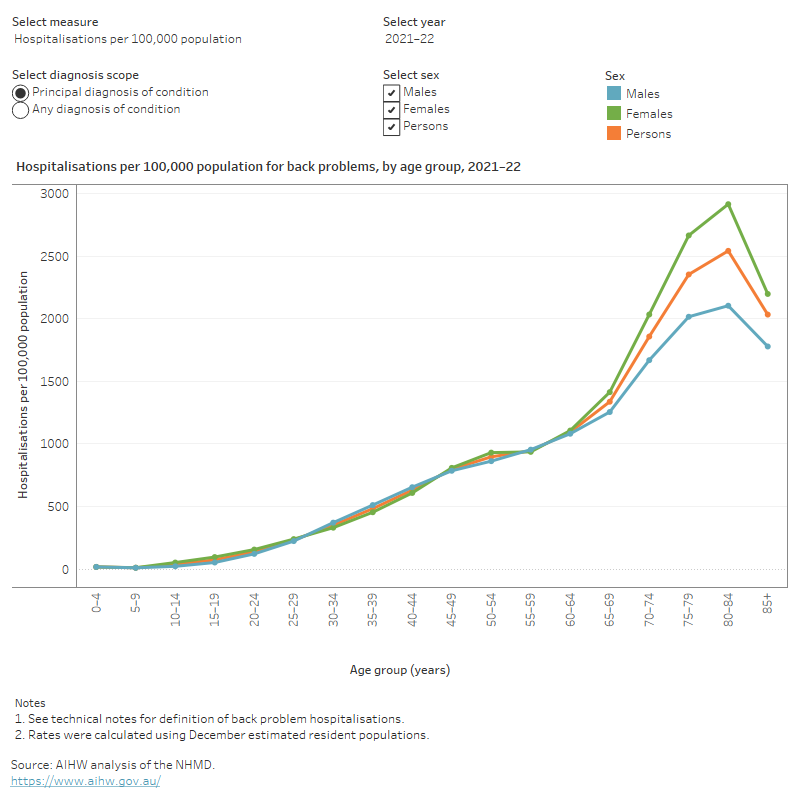

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, for back problems hospitalisations:

- rates were highest for peoples aged 80–84 years (2,500 per 100,000 population)

- rates were higher for females compared with males (740 compared with 630 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- the proportion of overnight hospitalisations was relatively high for people aged 10–14, 15–19, and 85 and over (79%, 58%, and 61%, respectively)

- the average length of stay of overnight hospitalisations was greatest for those aged 85 and over (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Age distribution for back problem hospitalisations, by sex, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows that hospitalisation rates for back problems increased with age up to the 80–84 age group, decreasing thereafter.

In 2021–22, back problem hospitalisations were composed of:

- back or spine pain (52%), of which lower-back-pain (27% of all back problem hospitalisations), neck-pain (6.2%), and radiculopathy (6.0%) were the most common

- vertebrae and disc disorders (43%), of which spinal stenosis (11%), lumbar and other intervertebral disc disorders with radiculopathy (8.9%), and spondylosis (8.7%) are common examples

- deforming dorsopathies (3.9%)

- other dorsopathies (1.7%).

Note: all percentages above represent proportion of total back problems hospitalisations.

Trends over time

From 2015–16 to 2021–22, little change was observed for hospitalisations due to back problems (between 600 and 660 per 100,000 population). The proportion and length of overnight stays also remained relatively stable (47% to 45% and 5.9 to 5.5 days, respectively (Figure 14).

Data prior to 2015–16 are not presented because rehabilitation hospitalisations were coded differently before this year.

It should be noted that the rate of hospitalisations over the past few years may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 14: Trends over time for back problem hospitalisations, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between 2015–16 and 2021–22, back problems hospitalisation rates were consistently higher for females compared with males.

Comorbidities of back problems

People with back problems often have other chronic conditions, known as a comorbidity. For this analysis, the following comorbidities were considered:

- arthritis

- asthma

- back problems

- cancer

- diabetes

- heart, stroke and vascular disease

- kidney disease

- mental and behavioural conditions

- osteoporosis or osteopenia.

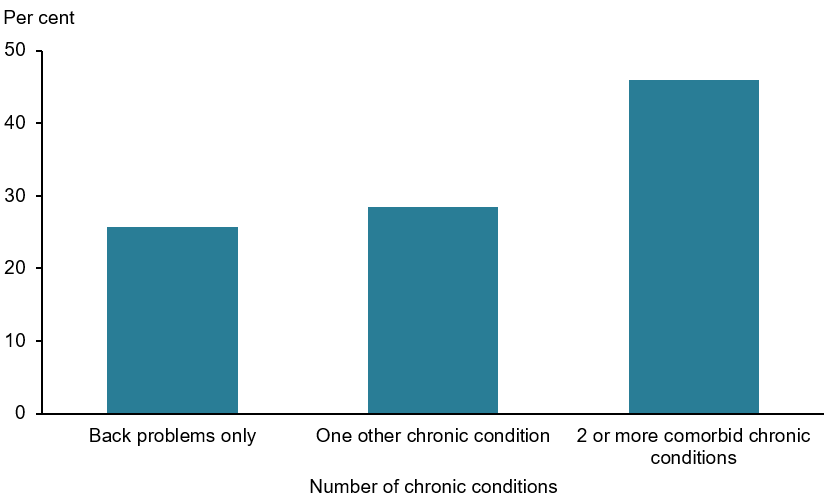

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, among people aged 45 and over with back problems:

- 74% also reported having one or more of the selected chronic conditions

- 46% also reported having two or more other chronic conditions (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Number of selected chronic conditions in people aged 45 years and over with back problems, 2017–18

Note: The 9 other selected chronic conditions are heart, stroke and vascular disease, asthma, arthritis, cancer, COPD, diabetes, kidney disease, mental and behavioural conditions, and osteoporosis.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 3.1).

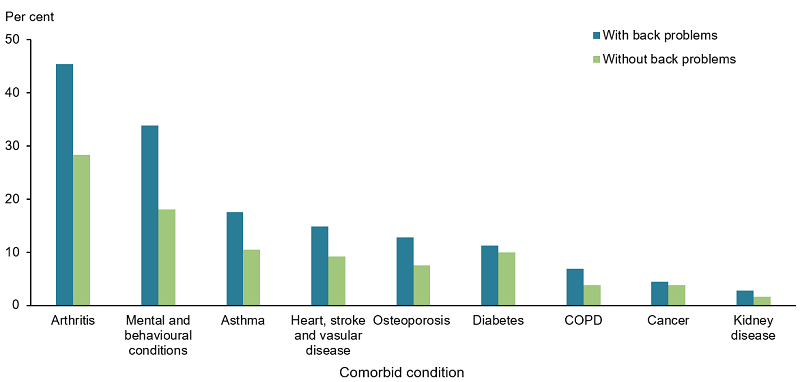

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, among people aged 45 and over with back problems:

- 48% had arthritis, compared with 29% without back problems

- 34% had mental and behavioural conditions, compared with 18% without back problems

- 17% had asthma, compared with 11% without back problems

- 16% had heart, stroke and vascular disease, compared with 10% without back problems.

These proportions remained similar even after accounting for differences in the age structure of the populations (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Prevalence of other chronic conditions in people aged 45 years and over with and without back problems, 2017–18

Notes:

- Rates are age-standardised to the Australian population as at 30 June 2001.

- Proportions do not total 100% as one person may have more than one additional diagnosis.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019a (Back problems 2023 Supplementary data table 3.2).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019a) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, AIHW analysis detailed microdata, accessed 28 April 2021.

ABS (2019b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: First Results, Australia, 2018–19, ABS website, accessed 1 May 2020.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 May 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023. doi:10.25816/e2v0-gp02.

AIHW (2022b) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

Almeida M, Saragiotto B, Richards B and Maher CG (2018) ‘Primary care management of non-specific low back pain: key messages from recent clinical guidelines’, The Medical Journal of Australia, 208(6):272–275, doi.org/10.5694/mja17.01152.

Britt H, Miller GC, Bayram C, Henderson J, Valenti L, Harrison C, Pan Y, Charles J, Pollack AJ, Chambers T, Gordon J and Wong C (2016) A decade of Australian general practice activity 2006–07 to 2015–16, General practice series no. 41, Sydney University Press, accessed 22 May 2023.

My HealthCity (2023) Musculoskeletal Health, My HealthCity website, accessed 4 October 2023.

Raspe H, Matthis C, Croft P and O'Neill T (2004) ‘Variation in back pain between countries: the example of Britain and Germany’, Spine, 29(9):1017–1021, doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200405010-00013.