Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease , AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd

MLA

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 14 December 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 19]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease , viewed 19 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Page highlights

What is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a preventable and treatable lung disease characterised by chronic obstruction of lung airflow that interferes with normal breathing and is not fully reversible.

- Health risk factors for COPD include smoking, living with obesity or being insufficiently active.

How common is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

An estimated 464,000 (4.8%) people in Australia aged 45 and over, reported having COPD in 2017–18.

Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- People with COPD had around double the rates of reporting ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health (52%), ‘moderate’ to ‘very high’ psychological distress (63%) and ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain (63%), compared with those without the condition.

- COPD accounted for 3.6% of the total disease burden and 50% of the total burden of disease due to respiratory conditions in 2023.

- In 2020–21, an estimated $831.6 million was spent on the treatment and management of COPD, representing 0.6% of total health system expenditure and 18% of expenditure for all respiratory conditions.

- COPD was the underlying cause of death in 7,018 deaths or 27.3 per 100,000 population in 2021, representing 4.1% of all deaths.

Treatment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In 2021–22, there were 53,000 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of COPD for people aged 45 and over (500 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).

Comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

90% of people with COPD had at least one other chronic condition – of the 9 conditions analysed, the top 3 comorbidities were arthritis (55%), asthma (43%) and mental and behavioural conditions (41%).

What is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a preventable and treatable lung disease characterised by chronic obstruction of lung airflow that interferes with normal breathing and is not fully reversible. The symptoms of COPD include cough, sputum production, and dyspnoea (difficult or laboured breathing). COPD symptoms often don't appear until significant lung damage has occurred, which usually worsens over time (WHO 2023).

It is worth noting that it can be difficult to distinguish COPD from asthma because the symptoms of both conditions can be similar – both have obstruction to the airways, both are chronic inflammatory diseases that involve the small airways (Buist 2003). Although the current definitions of asthma and COPD overlap, there are some important features that distinguish typical COPD from typical asthma. For more information, see Asthma.

Additionally, COPD and bronchiectasis share common symptoms of cough with sputum production and susceptibility to recurrent exacerbations (Hurst et al. 2015). Although these diseases present several common characteristics, they have different clinical outcomes. Therefore, it is very important to differentiate them at early stages of diagnosis, so appropriate therapeutic measures can be adopted (Athanazio 2012).

What causes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

COPD results from a complex interaction between genes and the environment. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), there are many causes of COPD, which may include:

- tobacco smoking: both active smoking and passive exposure to smoking. Although cigarette smoking is the most well studied COPD risk factor, it is not the only risk factor and there is consistent evidence from epidemiologic studies that non-smokers may also develop chronic airflow limitation

- genetic factors: a small number of people have a form of emphysema caused by a protein disorder called alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). This is where the body finds it difficult to produce one of the proteins (Alpha-1 antitrypsin) which usually protects the lungs. The lack of this protein can make a person more susceptible to lung diseases such as COPD

- lung growth and development factors: any factors that affect lung growth during gestation and childhood have the potential for increasing an individual’s risk of developing COPD, such as low birthweight, early childhood lung infections, abnormal lung growth and development (with normal decline in lung function over time) (Lange et al. 2015)

- environmental factors: working or living in areas where there is dust, gas, chemical agents and fumes, smoke or air pollution

- other chronic conditions: such as asthma and chronic bronchitis, which are associated with an increased likelihood of developing COPD (GOLD 2020).

How common is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

The development of COPD occurs over many years and therefore affects mainly middle aged and older people while asthma affects people of all ages. The prevalence of COPD increases with age, mostly occurring in people aged 45 and over.

In the 2017–18 NHS, the prevalence of COPD (captured here as self-reported emphysema and/or bronchitis) for people aged 45 and over:

- was 4.8%, or an estimated 464,000 people (ABS 2018)

- did not differ significantly overall between men and women (4.5% and 5.1% respectively), but for those aged 55–64, COPD was more prevalent in women compared with men (6.2% and 3.6%, respectively)

- increased with age to a peak of 7.7% for those aged 65–74 and then decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among people aged 45 and over, by sex and age group, 2017–18

Notes

- COPD here refers to self-reported current and long-term bronchitis and/or emphysema.

- COPD occurs mostly in people aged 45 and over. While it is occasionally reported in younger age groups, in those aged 45 and over there is more certainty that the condition is COPD and not another respiratory condition. For this reason only people aged 45 and over are included in this graph.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 1.1).

Using linked data to estimate the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among health service users in Australia

Linked data can provide a valuable source of information to monitor the prevalence of diagnosed COPD that is managed with specific prescriptions or requires emergency or hospital care.

More than 365,000 people aged 35 and over were identified with COPD in the National Integrated Health Service Information (NIHSI) data at 30 June 2019 based on their health service use in the year before, a prevalence of 2.7%. Almost 66,200 of those people where using health services for their COPD for the first time since July 2010. This equates to 181 new COPD service users every day.

Almost 184,000 women and more than 181,000 men were identified as having COPD at 30 June 2019. After age-standardisation, COPD prevalence remained fairly stable between 2017 and 2019 and was consistently higher among men than women.

The prevalence of COPD increased with age, ranging from 0.2% among those aged 35–44 to 10% among those aged 85 and over. These proportions were largely stable between 2017 and 2019.

At 30 June 2019, COPD prevalence was 3.6% in Inner regional areas, 3.3% in Outer regional, Remote and very remote areas and 2.3% in Major cities.

COPD prevalence was 3.8% in the lowest socioeconomic areas and 1.6% in the highest socioeconomic areas.

Of people aged 35 and over who used health services for their COPD in 2017–18, almost 7% (24,000 people) died in the following year. In contrast, 1.0% (135,000) of people not using COPD health service in the same period died in the following year.

This work adds to our understanding of the prevalence of COPD, and provides vital information on the use of health services by people with COPD to inform health service planning and assess the health and economic burden of the disease.

For more information, see Strengthening national COPD monitoring using linked health services data (AIHW 2023a).

Prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people

The AIHW uses ‘First Nations people’ to refer to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people in this report.

According to self-reported data from the ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), in 2018–19:

- about 17,800 (10%) First Nations people aged 45 and over, reported having COPD

- 13% of First Nations females reported having COPD compared with 6.7% of First Nations males

- the prevalence of COPD among First Nations people was 2.3 times as high as non-Indigenous people, after adjusting for differences in the age structures (ABS 2020a; ABS 2020b).

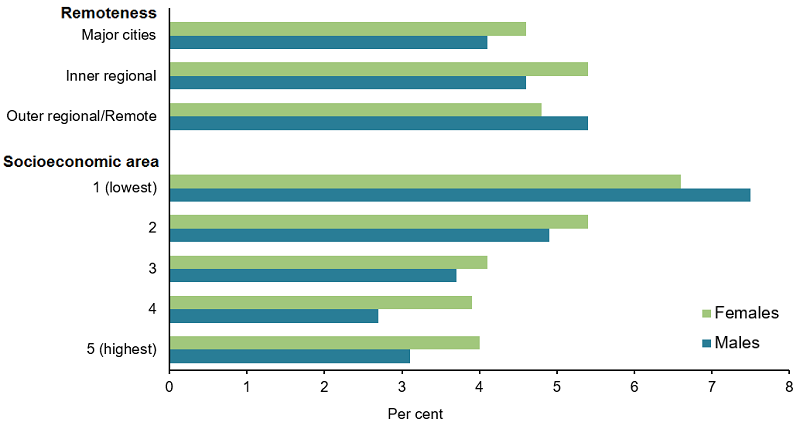

Variation between population groups

The prevalence of COPD among people aged 45 and over in Australia:

- did not vary significantly by remoteness area but it was affected by socioeconomic area

- was higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (males: 7.5% and 3.1%, respectively; females: 6.6% and 4.0%, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among people aged 45 and over, by sex, remoteness area and socioeconomic group, 2017–18

Notes

- Rates have been age-standardised to the 2001 Australian Standard Population as at 30 June 2001. Age groups: 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, 65-69, 70-74, 75+.

- COPD occurs mostly in people aged 45 and over. While it is occasionally reported in younger age groups, in those aged 45 and over there is more certainty that the condition is COPD and not another respiratory condition. For this reason only people aged 45 and over are included in this graph.

- Remoteness is classified according to the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) 2016 Remoteness Areas structure based on area of residence.

- Socioeconomic areas are classified according to using the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) based on area of residence.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 1.2).

Health risk factors associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COPD shares a number of risk factors with other chronic conditions, such as:

- increasing age

- genetic predisposition

- smoking or exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (including in childhood)

- exposure to fumes and smoke from carbon-based cooking and heating fuels, such as charcoal and gas

- occupational hazards (for example, exposure to pollutants and chemicals)

- poor nutrition

- pneumonia or childhood respiratory infection (AIHW 2017).

In people with COPD, risk factors for poor health outcomes such as worsening symptoms, exacerbations (flare-ups) and increased risk of death include:

- smoking and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke

- influenza and pneumococcal infection

- malnutrition/ obesity

- insufficient physical activity

- presence of comorbidities (Yang et al. 2019).

For COPD, as for many other chronic conditions, there are 2 types of risk factors: those that increase the chance of developing COPD in the first place, and those that increase the chance that a person who already has COPD will develop additional health problems. Risk factors also vary according to the person's age.

Finding a risk factor that is associated with an increased risk of developing COPD, or an increased risk of poor health outcomes in COPD, does not necessarily mean that the risk factor caused these problems, or that they can be prevented. However, there is overwhelming evidence that smoking and exposure to biomass fuels are major causes of COPD (AIHW 2017).

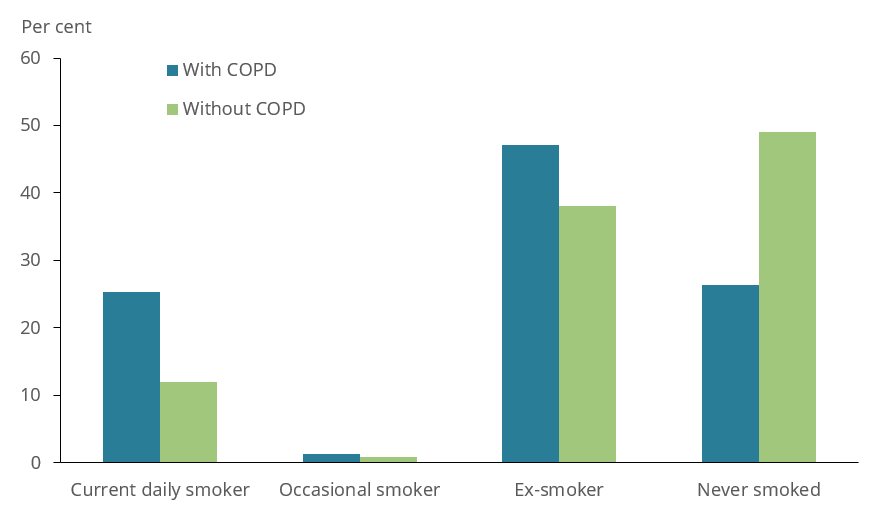

Smoking status

Based on the 2017–18 NHS, people with COPD aged 45 and over:

- were 2.1 times more likely to be current daily smokers compared with people without COPD (25% and 12%, respectively)

- were 1.2 times more likely to be an ex-smoker compared with people without COPD (47% and 38%).

It is worth noting that one quarter (26%) of people aged 45 and over with COPD had never smoked (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Smoker status of people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 2.2).

Physical activity

Based on the 2017–18 NHS, people with COPD aged 45 and over were 1.3 times more likely to be insufficiently physically active (not to meet the 2014 physical activity guidelines) compared with people without COPD (76% and 60%, respectively) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Physical activity in people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 2.3).

Body mass

Based on the 2017–18 NHS, people with COPD aged 45 and over were more likely to be living with obesity compared with people without COPD (43% and 38%, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Body mass index (BMI) distribution in people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Note: Based on body mass index (BMI) for persons whose height and weight was measured and imputed. In 2017–18, 33.8% of respondents aged 18 years and over did not have a measured BMI. For these respondents, imputation was used to obtain BMI. For more information, see Appendix 2: Physical measurements in the 2017–18 National Health Survey (ABS 2018).

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 2.4).

Age differences in risk factors in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Based on the 2017–18 NHS, people with COPD aged 45–64 were:

- more likely to be a current daily smoker compared with those aged 65 and over (38% and14%, respectively)

- less likely to be insufficiently physically active compared with people with COPD aged 65 years and over (68% and 82%, respectively).

The difference in obesity between the two age groups was not statistically significant (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Prevalence of selected risk factors in people aged 45 and over with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, by age group, 2017–18

Note: Overweight and obese are based on body mass index (BMI) for persons whose height and weight was measured and imputed. In 2017–18, 33.8% of respondents aged 18 years and over did not have a measured BMI. For these respondents, imputation was used to obtain BMI. For more information, see Appendix 2: Physical measurements in the 2017–18 National Health Survey (ABS 2018).

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 2.5).

Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COPD can interrupt daily activities, sleep patterns and the ability to exercise and people with COPD generally rate their health worse than people without the condition.

How does chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affect quality of life?

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, after adjusting for differences in age structure, people aged 45 and over with COPD were:

- less likely to describe their health as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’, and 2.7 times as likely to report ‘fair’ to ‘poor’, compared with those without COPD (52% and 19%, respectively) (Figure 7)

- 2.0 times as likely to experience ‘moderate’ to ‘very high’ levels of psychological distress compared with people without COPD (63% and 32% respectively) (Figure 8)

- 1.9 times as likely to experience ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe bodily pain’ compared with those without COPD (63% and 33%, respectively) (Figure 9).

Figure 7: Self-assessed health of people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Notes

- Rates have been age-standardised to the 2001 Australian Standard Population as at 30 June 2001. Age groups: 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75+.

- COPD occurs mostly in people aged 45 and over. While it is occasionally reported in younger age groups, in those aged 45 and over there is more certainty that the condition is COPD and not another respiratory condition. For this reason, only people aged 45 and over are included in this graph.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 3.1).

Figure 8: Psychological distress experienced by people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Notes

- Rates have been age-standardised to the 2001 Australian Standard Population as at 30 June 2001. Age groups: 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, 65-69, 70-74, 75+.

- COPD occurs mostly in people aged 45 and over. While it is occasionally reported in younger age groups, in those aged 45 and over there is more certainty that the condition is COPD and not another respiratory condition. For this reason, only people aged 45 and over are included in this graph.

- Psychological distress is measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), which involves 10 questions about negative emotional states experienced in the previous 4 weeks. The scores are grouped into Low: K10 score 10–15, Moderate: 16–21, High: 22–29, Very high: 30–50.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 3.2).

Figure 9: Pain experienced by people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Notes

- Rates have been age-standardised to the 2001 Australian Standard Population as at 30 June 2001. Age groups: 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, 65-69, 70-74, 75+.

- COPD occurs mostly in people aged 45 and over. While it is occasionally reported in younger age groups, in those aged 45 and over there is more certainty that the condition is COPD and not another respiratory condition. For this reason, only people aged 45 and over are included in this graph.

- Bodily pain experienced in the 4 weeks prior to interview.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 3.3).

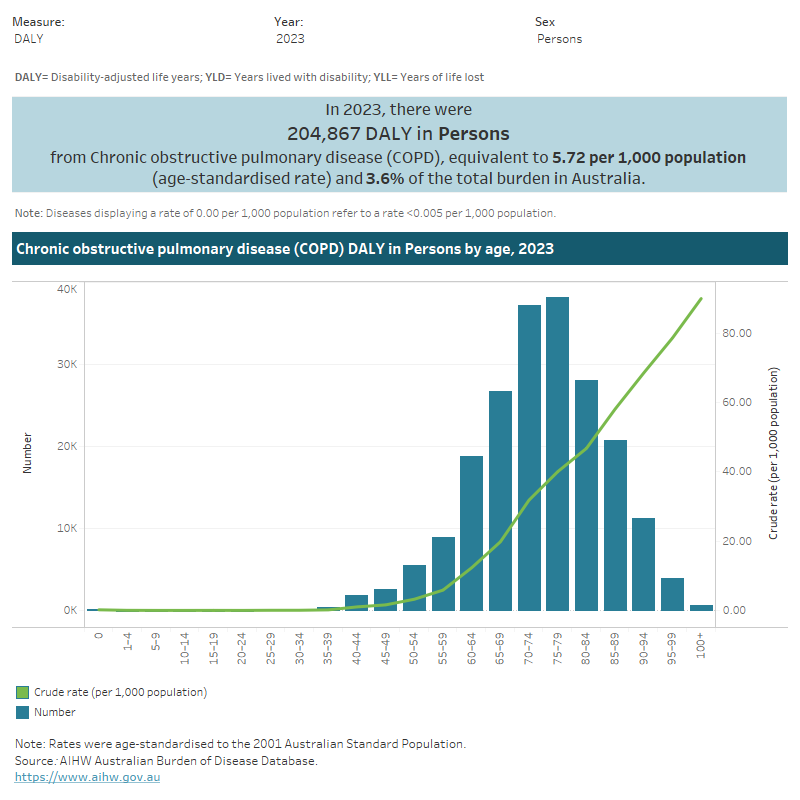

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

In 2023, COPD was the fourth leading cause of burden and accounted for 3.6% of total disease burden (DALY); 3.2% of non-fatal burden (YLD), and 4.1% of fatal burden (YLL). Within the respiratory conditions disease group, COPD accounted for 50% of total burden (DALY); 38% of non-fatal burden (YLD); and 71% of fatal burden (YLL) (AIHW 2023b).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023:

- the rate of total burden (DALY) increased steeply between the ages of 55–59 and 75–79 (5.9 to 40.1 DALY per 1,000 population)

- males had a higher proportion of fatal burden (YLL) than females (53% and 47% respectively)

- COPD was the leading cause of total burden in women aged 70–74 and 75–79 (31.7 and 40.6 DALYs per 1,000 population, respectively) and the second leading cause of total burden in men aged 70–74 and 75–79 (32.1 and 39.6 DALYs per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Burden of disease due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by age, sex and year

This figure shows that females with COPD had a higher proportion of non-fatal burden (YLD) than males with COPD in 2023.

Trends over time

Between 2003 and 2023, after adjusting for differences in age structure, the rate of COPD burden decreased by 13% (from 6.6 DALY to 5.7 DALY per 1,000 population) – or 0.7% per year on average.

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023 (AIHW 2023b).

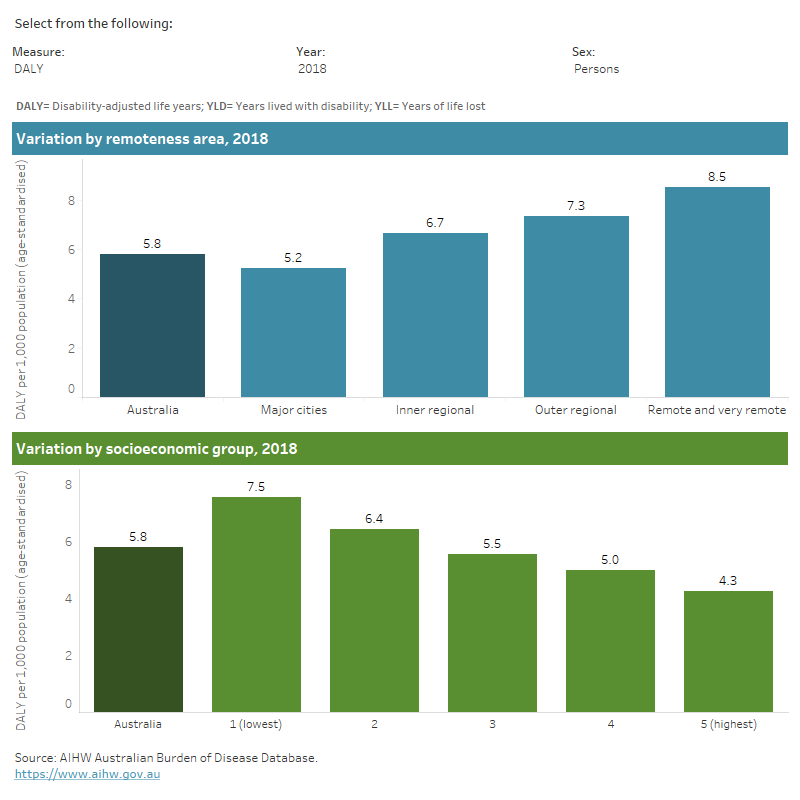

Variation between population groups

In 2018, after adjusting for differences in age structure, rates of COPD total burden (DALY) and fatal burden (YLL) increased with increasing remoteness, and with decreasing socioeconomic area.

People living in Remote and very remote areas were:

- 1.6 times as likely to experience COPD burden compared with people living in Major cities (8.5 and 5.2 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- 2.4 times as likely to experience fatal burden (YLL) for COPD compared with people living in Major cities (5.8 and 2.5 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively).

People living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) were:

- 1.8 times as likely to experience COPD burden compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (7.5 and 4.3 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- 3.2 times as likely to experience fatal burden (YLL) for COPD compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (4.8 and 1.5 YLL per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 11) (AIHW 2021).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden.

Figure 11: Burden of disease due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by remoteness area and socioeconomic group, sex and year

This figure shows that of people with COPD living in Remote and very remote areas, males had higher rates of total burden than females.

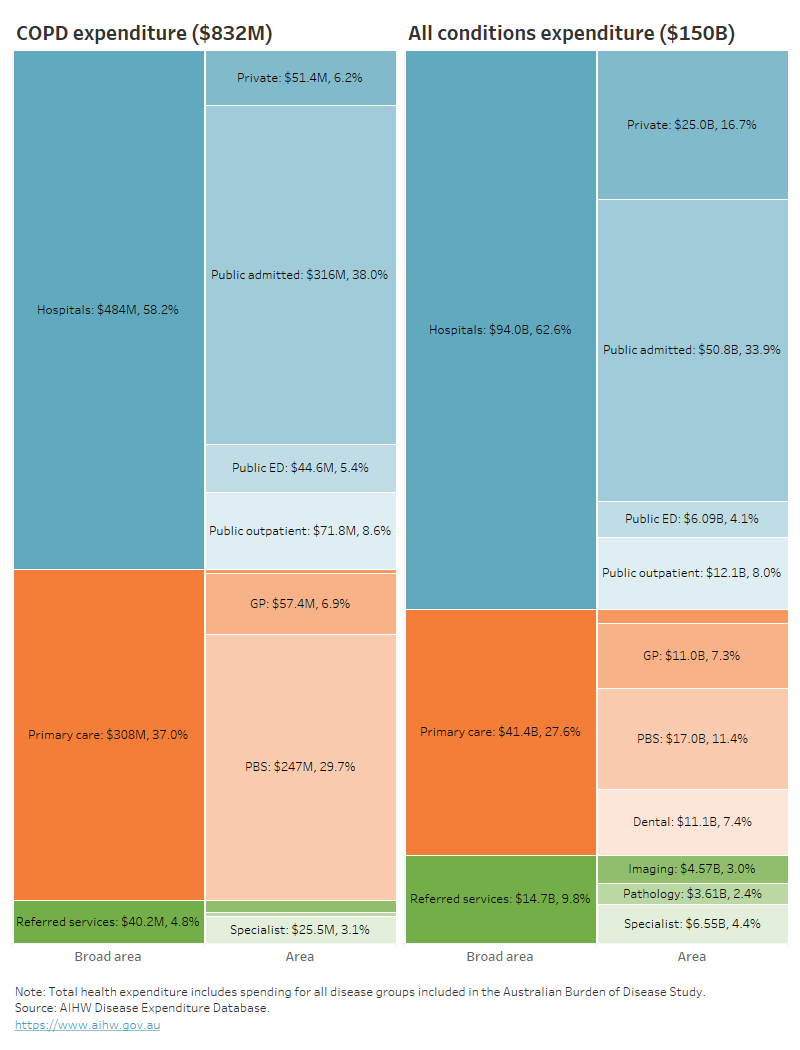

Health system expenditure

In 2020–21, an estimated $831.6 million was spent on the treatment and management of COPD, representing 0.6% of total health system expenditure and 18% of expenditure for all respiratory conditions (AIHW 2023c).

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–21:

- hospital services represented 58% ($483.6 million) of COPD expenditure, similar to the proportion of total health expenditure for hospital services (63%)

- primary care accounted for 37% ($307.8 million) of COPD expenditure, around 1.3 times the primary care portion of total health expenditure (28%). The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) proportion of COPD expenditure was especially large in comparison to the average, 2.6 times the proportion for total health expenditure (30% and 11%, respectively)

- referred medical services represented 4.8% ($40.1 million) of COPD expenditure, which was approximately half the referred medical services portion of total expenditure (9.8%) (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease expenditure attributed to each area of the health system, with comparison to all disease groups, 2020–21

This figure shows that $197 million (25%) of COPD expenditure was attributed to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

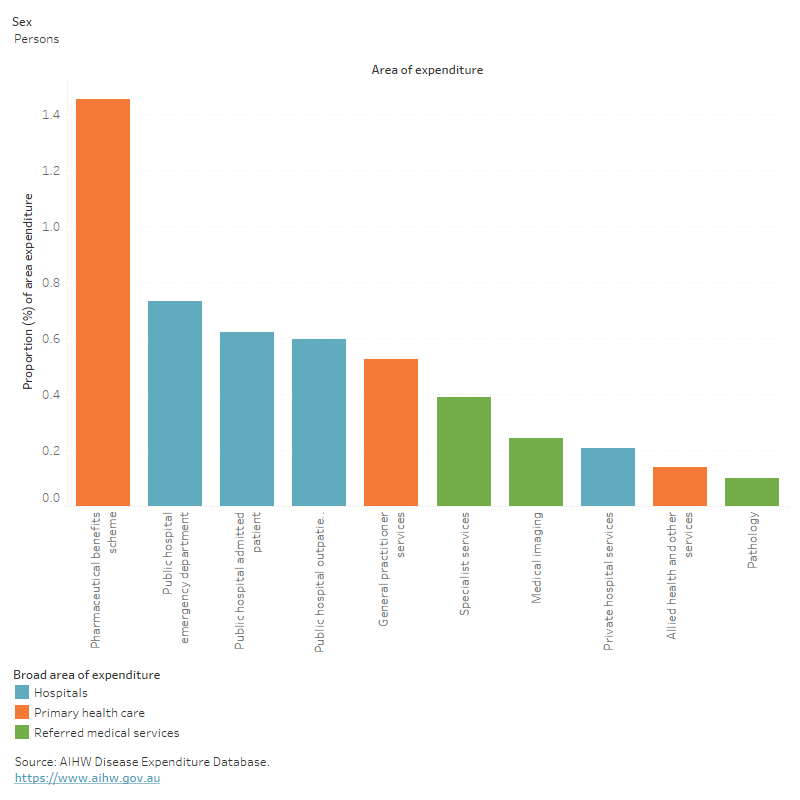

In 2020–21, COPD accounted for:

- 1.5% ($247.2 million) of all PBS expenditure

- 0.6% ($315.9 million) of all public hospital admitted patient expenditure (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Proportion of expenditure attributed to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, for each area of the health system, 2020–21

This figure shows that 1.9% of COPD expenditure was attributed to public hospital emergency departments, admitted patient and outpatient services.

Who is the money spent on?

In 2020–21:

- the age distribution of spending on COPD reflects the prevalence distribution, with most spending being for older age groups (98% for people aged 45 and over)

- 7% more COPD expenditure was attributed to males compared with females (444.7 million and $385.7 million, respectively) with the remaining $1.2 million (0.1%) unattributed to any sex (Figure 13).

Further detail is available in Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21.

In 2018–19, it was estimated that COPD expenditure per case was:

- 21% greater for males compared with females ($1,700 and $1,400 per case, respectively)

- 67% higher than respiratory conditions as a group ($1,600 and $510 per case, respectively) (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors.

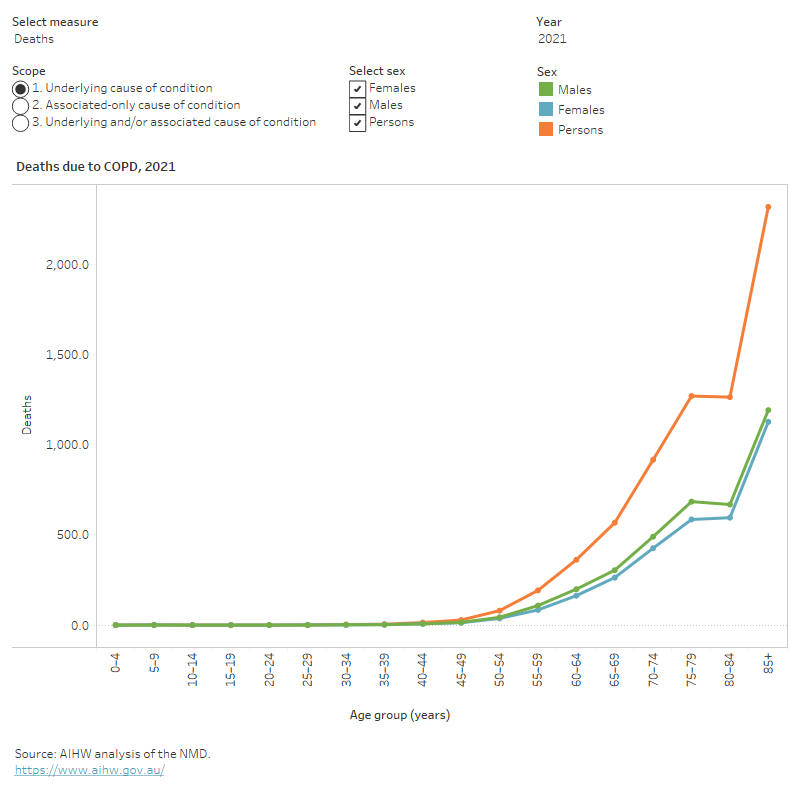

How many deaths were associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

COPD is a major cause of death in Australia. COPD was recorded as an underlying cause of death for 7,018 deaths or 27.3 per 100,000 population in Australia in 2021, representing 4.1% of all deaths and 52% of all respiratory deaths.

COPD was more likely to be recorded as an associated cause of death. An additional 9,663 deaths had an associated cause of COPD recorded, resulting in a total of 16,681 deaths in Australia due to, or associated with, COPD. This represented 9.7% of all deaths and 36% of respiratory deaths.

Variation by age and sex

In 2021, COPD mortality (as the underlying cause of death) was similar to the profile for all deaths, and was concentrated amongst:

- older people (69% compared with 67% for total deaths for those aged 75 and over, respectively)

- males (53% compared with 52% for total deaths for males, respectively) (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Age distribution for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality, by sex, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that the death rates due to COPD increased with age and was highest for people aged 85 and over in 2021.

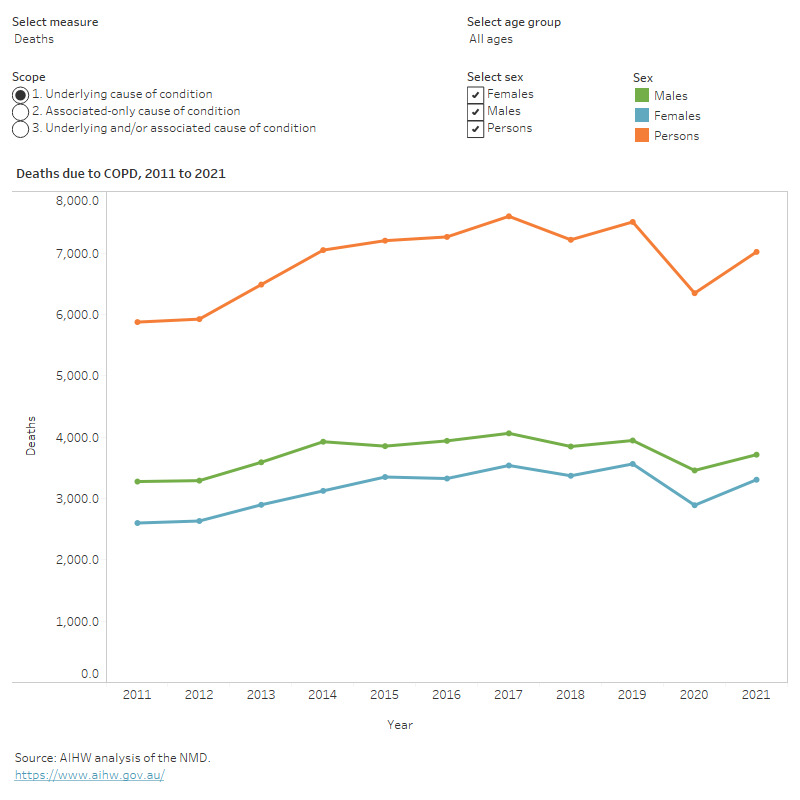

Trends over time

After adjusting for differences in age structure, mortality rates for COPD (as the underlying cause) between 2011 and 2021 were:

- relatively stable (around 23 per 100,000 population), until 2019 and then dipped to 19 and 20.5 per 100,000 population in 2020 and 2021, respectively

- 1.4 to 1.7 times higher for males compared with females (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Trends over time for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that the death rate due to COPD (for underlying cause of death) was highest in 2014 and lowest in 2020.

Variation between population groups

In 2021, after adjusting for differences in age structure, mortality rates for COPD (as the underlying cause) were:

- 2.1 times higher for people living in Remote and very remote areas compared with people living in Major cities (37 and 18 per 100,000 population, respectively).

- 2.6 times higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (28 and 11 per 100,000 population, respectively).

The same patterns across population groups were seen for COPD deaths as an underlying cause or any cause (underlying or associated cause) of death.

For more information on mortality data, see the Chronic respiratory condition mortality data tables 2023.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality and smoking trends

The main risk factor for the development and progression of COPD is smoking, with smokers being 12 to 13 times more likely to die from COPD than non-smokers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014).

Improvements in COPD mortality rates are expected to follow decreases in smoking rates, with a time-lag in-between. This is because chronic conditions, such as COPD, have a long latency period i.e. smoking early in life is involved in initiating disease processes prior to the disease being diagnosed (Lynch and Smith 2005).

In Australia, the smoking rate of adults aged 18 and over decreased from 1980 to 2019 for both men and women, with men having consistently higher smoking rates than women (men: 41% to 14%; women: 30% to 12%) (Figure 16) (Greenhalgh et al. 2023).

For more information on the history of smoking and COPD, see Mortality from asthma and COPD in Australia (AIHW 2014). This report presents detailed analysis of COPD mortality from 1965 to 2010.

Figure 16: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease death rates of people aged 45 and over, 3-year moving average, and smoking rates, 1980 to 2020

Notes

- COPD deaths are shown as a 3-year moving average. For example, the 2020 data point represents the average of 2019, 2020 and 2021.

- From 1979 to 1996, COPD classified according to ICD-9 codes 490, 491, 492, 496; from 1997 to 2021, COPD classified according to ICD-10 codes J40–J44. COPD occurs mostly in people aged 45 years and over. While it is occasionally reported in younger age groups, in those aged 45 years and over there is more certainty that the condition is COPD and not another respiratory condition. For this reason, only people aged 45 years and over are included in this table.

- Smoking refers to people those reporting that they smoke 'daily' or 'at least weekly', and smoking any combination of combustible cigarettes, cigars, pipes or waterpipes. It does not include use of electronic cigarettes/vapes or other personal vaporising devices where users inhale vapour rather than smoke.

- Smoking data were calculated by the Cancer Council of Victoria. Smoking rates for 1980–1992 were sourced from surveys conducted by the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria; smoking rates for 1995–2019 were sourced from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey. Blank cells mean that data was not available.

- In this report, deaths registered in 2018 and earlier are based on the final version of cause of death data; deaths registered in 2019 are based on the revised version; and deaths registered in 2020 and 2021 are based on the preliminary version. Revised and preliminary versions are subject to further revision by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

Source: AIHW analysis of the AIHW National Mortality Database, Scollo and Winstanley 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 4.1).

Treatment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The Department of Health’s National Strategic Action Plan for Lung Conditions (the Action Plan) provides a detailed, person-centred roadmap for treating and managing COPD, among several other lung conditions (Department of Health 2019).

The Action Plan outlines a comprehensive, collaborative and evidence-based approach to reducing the individual and societal burden of lung conditions and improving lung health (Department of Health 2019).

The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of COPD (the COPD-X Guidelines) summarises current evidence around optimal management of people with COPD, and provides a decision support aid for general practitioners, other primary health care clinicians, hospital-based clinicians and specialists working in respiratory health (Yang et al. 2019).

What role do GPs play in treating and managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

General practitioners (GPs) are often the first point of contact for people who develop COPD. Until 2017, the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) survey was the most detailed source of data about general practice activity in Australia (Britt et al. 2016).

In the 10-year period from 2006–07 to 2015–16, according to the BEACH survey, the estimated rate of COPD management in general practice was around 0.9 per 100 encounters (Britt et al. 2016).

It is worth noting that there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection to monitor provision of care by GPs. See General practice, allied health and other primary care services.

What interventions are used to treat and manage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

Currently, the only intervention that has been shown to slow the long-term deterioration in lung function associated with COPD is assisting smokers to quit (Mosenifar 2022). Other interventions for COPD that can help maintain quality of life and reduce symptoms are: immunisations, pulmonary rehabilitation, medications, and, for people with very severe disease, long-term oxygen therapy.

Some information is available on use of medications by patients with COPD, however, there is currently a lack of nationally comparable information about access to and utilisation of pulmonary rehabilitation and oxygen therapy. Options for improving data about these interventions are discussed in the report Monitoring pulmonary rehabilitation and long-term oxygen therapy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Australia – a discussion paper (AIHW 2013).

Smoking cessation

The most beneficial step in any treatment plan for COPD patients is to stop smoking. Stopping smoking is the only intervention that has been shown to improve the natural progression of COPD. For example, it helps to improve a patient’s cough, ease breathlessness and slow down further lung damage (Yang et al. 2022).

Immunisation

Vaccination reduces the risks associated with influenza and pneumococcal infection, which are leading causes of exacerbations and healthcare visits. Therefore, influenza immunisation and pneumococcal immunisation is recommended for all patients with COPD (Yang et al. 2022).

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is one of the most effective interventions for COPD and is recommended for all patients with COPD who are short of breath on exertion, including in the period following an acute exacerbation (Spruit et al. 2013; Alison et al. 2017). According to Spruit, pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive intervention, mainly involving exercise training, education, and behaviour change. It is designed based on a thorough patient assessment followed by patient-tailored therapies (Spruit et al. 2013). Strong evidence supports pulmonary rehabilitation is effective for COPD patients to improve their physical and emotional condition, long-term adherence to health behaviours, quality of life and reduce hospitalisations, thus helping them improve their independence and functioning in the community (Gordon et al. 2019; McCarthy et al. 2015; Puhan et al. 2016).

Pulmonary rehabilitation is commonly delivered by an interdisciplinary team of therapists and may comprise various associated supportive strategies (Alison et al. 2017). It mainly includes the following components:

- Exercise training – the cornerstone foundation of pulmonary rehabilitation. This aims to build patient confidence, maximise skeletal muscle function, optimise cardiovascular fitness and promote self-sustaining healthy physical activity behaviours.

- Education – involves the provision of tailored advice to improve people’s understanding of their lung disease, awareness of self-management strategies, how to exercise safely, how to use medicines, how treatment works, and when to ask for help. Education may be provided in various formats such as group discussions or resources. Identifying individual support needs (e.g. assistance to quit smoking) is an essential goal of education.

- Nutrition counselling – the provision of individually tailored dietary support to optimise nutritional intake and control weight loss or gain. In people with COPD, both excess weight and low weight are associated with increased morbidity. Obesity increases the work of breathing, while poor nutritional status and insufficient energy intake may lead to impaired muscle function, which can accelerate deconditioning and worsen symptoms such as breathlessness.

- Psychosocial support – People with COPD are vulnerable to developing symptoms of anxiety and depression, which can worsen quality of life and disability. Support is often provided by peer participants, support groups, social workers or external organisations. This may involve emotional support, social support, or the development of coping strategies to help people better manage COPD. Mental health specialists may provide additional expert support, if required, for clinically significant symptoms of anxiety or depression (Alison et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2022).

Pulmonary rehabilitation may be provided in hospital outpatient departments, in community facilities or at home. Hospital-based programs are often considered ‘usual care’, however community-based programs of equivalent frequency and intensity can be offered to people with COPD as a suitable alternative (Alison et al. 2017). Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation programs should include regular contact with an exercise specialist to facilitate appropriate participation and progression.

Medications

Medications are used in COPD treatment to prevent and control symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations and improve exercise tolerance. Some drugs used to treat COPD are also used to treat other respiratory conditions such as asthma. For more information, see Respiratory medication use in Australia 2003–2013: treatment of asthma and COPD.

Several medications are available for treatment of COPD in Australia, including long-acting bronchodilators used both separately and in combination with inhaled corticosteroids or other bronchodilators. Bronchodilators are drugs that can relax and dilate the bronchial passageways and therefore improve the passages of air into the lungs. It is worth mentioning that the majority of the medications used in COPD treatment are delivered via inhalers, so good inhaler technique and adherence to treatment are important for optimal treatment outcome (George and& Bender 2019).

Oxygen therapy

Long term oxygen therapy (LTOT) – the provision of supplemental oxygen therapy for 15 hours per day or more – can be prescribed for people with persistently low levels of oxygen in the blood, including from chronic lung disease, most commonly advanced COPD. LTOT reduces mortality in COPD and may also have a beneficial impact on aspects of quality of life (Yang et al. 2022). Although effective, it is a potentially expensive and cumbersome therapy that should only be prescribed for those in whom there is evidence of benefit (Yang et al. 2022). In Australia, LTOT is mostly delivered in the home using an oxygen concentrator, a device that removes nitrogen from room air, thereby increasing the concentration of oxygen. Sometimes oxygen cylinders are provided for short-term or portable use.

Non-invasive ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) refers to the administration of ventilatory support using a face mask, nasal mask, or a helmet, rather than an invasive artificial airway (such as a tube). Air, usually with added oxygen, is given to patient through the mask under positive pressure, where the amount is altered depending on whether the patient is breathing in or out. NIV has now become an integral tool in the management of acute and chronic respiratory failure, in both the home setting and in the critical care unit.

The current evidence shows that NIV is effective in preventing respiratory failure after extubation (removal of a tube previously inserted into a patient's body) (Ferrer et al. 2009) and treating patients with an acute exacerbation of COPD and other disorders characterised by hypoventilation (Ram et al. 2004; Osadnik 2017).

What role do hospitals play in treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

Patients may require admission to hospital for severe acute exacerbations of COPD. Acute exacerbations of COPD (flare-ups) are frequently due to respiratory tract infections but have also been associated with increases in exposure to air pollution and changes in ambient temperature.

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that for people aged 45 and over in 2020–21, there were 128,000 hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of COPD, representing 1.6% of all hospitalisations.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of COPD, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of COPD.

For people aged 45 and over, in 2021–22:

- there were 53,000 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of COPD, representing 0.7% of all hospitalisations, and 500 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- COPD accounted for 268,000 bed days, representing 1.2% of all bed days

- 90% of COPD hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 5.5 days (Figure 18).

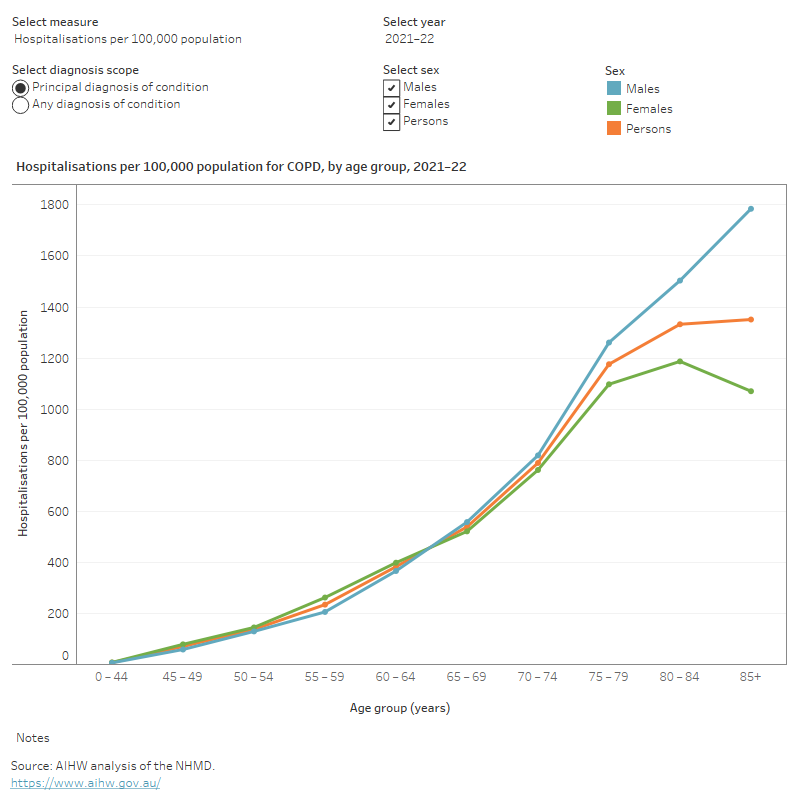

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, COPD hospitalisation rates for persons aged 45 and over:

- increased with age and were highest for people aged 85 and over (1,400 per 100,000 population)

- were 1.1 times higher for males compared with females (510 and 485 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 17).

Figure 17: Age distribution for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalisations, by sex, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that in 2021–22, hospitalisation rates for COPD were lowest for people aged 45–49 for males and females.

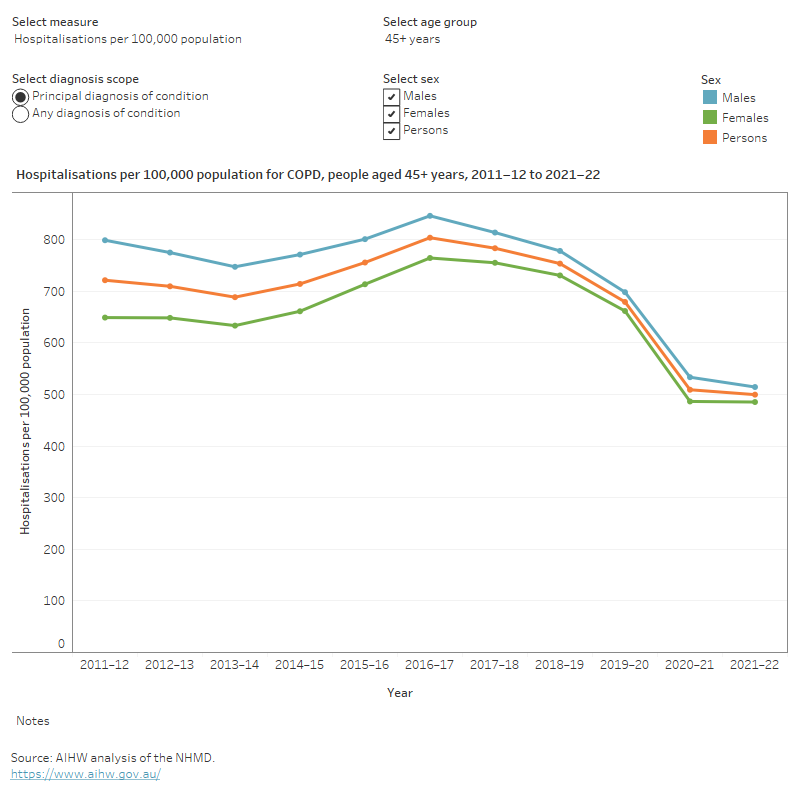

Trends over time

From 2011–12 to 2021–22, for COPD hospitalisations for persons aged 45 and over:

- the rate decreased from 720 to 500 per 100,000 population

- the proportion of overnight stays decreased slightly from 92% to 90%

- the average length of overnight stays decreased slightly from 6.5 to 5.5 days (Figure 18).

It should be noted that the rates of hospitalisations over the past few years have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. For more information on this, see the Chronic respiratory conditions COVID-19 impact section.

Figure 18: Trends over time for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalisations, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between the hospitalisation rates for people aged 45 and over followed the same pattern over time for males and females.

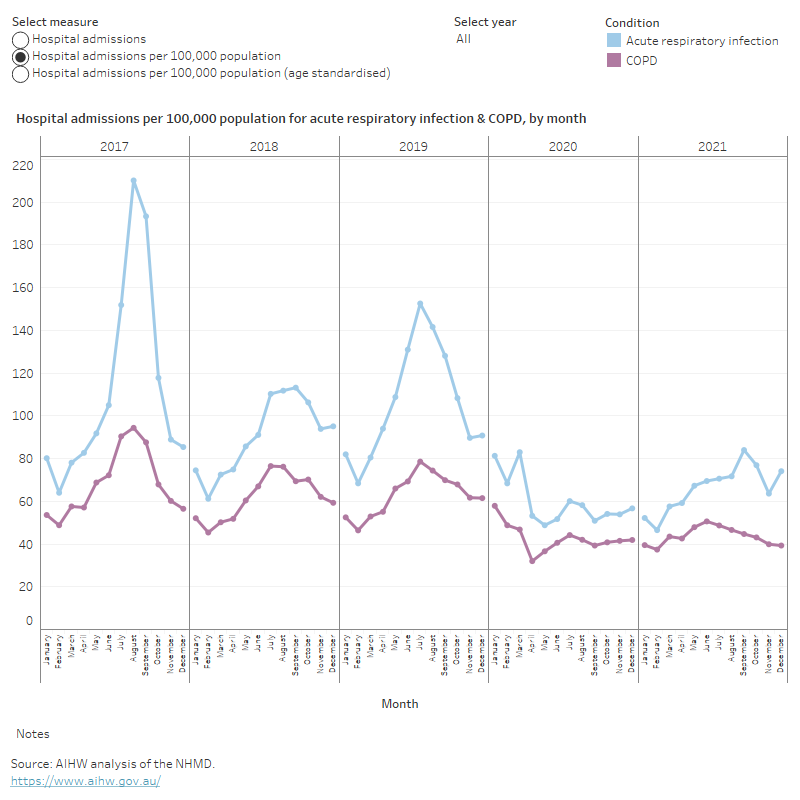

Seasonal variation in hospitalisations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Admissions to hospital for COPD are typically highest in winter and early spring and is consistent with the trend for acute respiratory infections, such as rhinovirus (common cold), influenza, pneumonia and acute bronchitis (Figure 19).

2020 was an exception to this general trend, and hospitalisations were lower overall across the entire year. This was likely due to lockdown mandates related to COVID-19 across the nation. The lower rate persisted into 2021, but more typical seasonal variation over the course of the year was observed.

Figure 19: Hospitalisations due to acute respiratory infection (ARI) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, by month, 2017–2021

This figure shows that hospitalisations rates for acute respiratory infections were highest in August 2017 and lowest in February 2021.

Comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

People with COPD often have other chronic and long-term conditions. This is called ‘comorbidity’, which describes any additional disease that is experienced by a person with a disease of interest (the index disease). Comorbidities often share common risk factors, and are increasingly seen as acting together to determine the health outcome.

People in Australia diagnosed with one or more chronic conditions often have complex health needs, die prematurely and have poorer overall quality of life (AIHW 2018). In terms of comorbidities, in 2017─18 one in 5 people (20%) had 2 or more chronic conditions (ABS 2018).

As people age, they are more likely to have more than one chronic condition. Because COPD is more likely to occur in older people, people with COPD also commonly experience a range of other chronic conditions (Chatlia et al. 2008; Divo et al. 2012). These comorbidities contribute to ill health and risk of death in all stages of COPD, and the incidence of hospitalisation for non-respiratory causes is increased in patients with COPD (Franssen and Rochester 2014).

In February 2019, the Department of Health released the National Strategic Action Plan for Lung Conditions (the Action Plan), which includes COPD in its scope. The Action Plan ‘provides a detailed, person-centred roadmap for addressing one of the most urgent chronic conditions facing Australians’ (Department of Health 2019). For more information, see National Strategic Action Plan for Lung Conditions.

Comorbidities can complicate management options and multiply the effects of chronic conditions (van der Molen 2010). Physicians may need to prescribe medications for one condition that may exacerbate another existing comorbid condition. For example, some bronchodilator medications prescribed for COPD may worsen glaucoma (increased pressure in the eyes), or can cause urinary problems in men with an enlarged prostate. Use of steroid tablets for COPD exacerbations (or flare-ups) may contribute to weakening of the bones (osteoporosis).

COPD has a high rate of comorbidity with cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Bhatt et al. 2014). Beta‑blocker medications are recommended for management of acute coronary syndromes, cardiac failure and sometimes for irregular heartbeat and hypertension. However, these medications can cause severe flare-ups in people with asthma and so have frequently been withheld from people with COPD. Despite this, recent evidence suggests that beta-blockers may be safe and helpful for managing COPD (Bhatt et al. 2016), though the COPD-X Plan states that despite a paucity of evidence to suggest harm, beta-blockers are still under-utilised in COPD for guideline-based indications such as systolic heart failure (Yang et al. 2019).

Establishing a better understanding of the common comorbidities of COPD may help with the diagnosis of comorbid conditions. For example, coronary artery disease is common in patients with COPD and is underdiagnosed (Reed et al. 2012). Optimal management of any individual patient with COPD should include identification and management of comorbidities and anticipation of increased risks associated with those comorbidities in the presence of COPD (Yang et al. 2019).

Prevention and diagnosis can be improved by a better understanding of risk factors for the development of COPD. Tobacco smoking, air pollution, poor nutrition and serious childhood lung infections are all known risk factors for developing COPD (Yang et al. 2019). More information on risk factors can be found in the section Risk factors associated with COPD.

Treatment strategies that target modifiable behaviours can be used to manage various chronic diseases, for example, diet, exercise, weight control, and smoking cessation or reduction (Bauer et al. 2014). Smoking cessation is the most important intervention to prevent the worsening of COPD (Yang et al. 2019).

This COPD comorbidity analysis included arthritis, back problems, cancer, chronic asthma, diabetes, heart, stroke and vascular disease, kidney disease, mental and behavioural conditions and osteoporosis or osteopenia. These 9 chronic conditions have been selected because they are common in the general community, pose significant health problems, have been the focus of ongoing national surveillance efforts, and action can be taken to prevent their occurrence (ABS 2022b).

Additional chronic conditions that are commonly found in people with COPD, and that can impact on COPD, include bronchiectasis (a condition in which the airway walls are damaged and the person has excessive mucus production and frequent chest infections) and obstructive sleep apnoea (Yang et al. 2019).

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, 90% people aged 45 and over, who currently have COPD, also reported having one or more of the 9 selected chronic conditions (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Comorbidity of selected chronic conditions in people aged 45 and over with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Note: The 9 other selected chronic conditions include arthritis, asthma, back problems, cancer, diabetes, heart, stroke and vascular disease, kidney disease, mental and behavioural conditions and osteoporosis.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 5.1).

Types of comorbid chronic conditions in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Of those aged 45 and over who had COPD:

- 55% also had arthritis (compared with 33% for people without COPD)

- 43% also had asthma (compared with 11% for people without COPD)

- 41% also had mental and behavioural conditions (compared with 21% of people without COPD)

- 40% also had back problems (compared with 25% for people without COPD)

- 26% also had heart, stroke and vascular disease (compared with 10% of people without COPD) (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Prevalence of other chronic conditions in people aged 45 and over with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2017–18

Notes

- COPD here refers to self-reported current and long-term bronchitis and/or emphysema.

- Proportions may not add to 100% as a person may have more than one additional diagnosis.

Source: ABS 2019 (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2023 Supplementary data table 5.2).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) National Health Survey: First results, ABS Website, accessed 2 June 2023.

ABS (2019) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, detailed microdata, DataLab. ABS cat no. 4324.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Findings based on AIHW analysis of ABS microdata.

ABS (2020a) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19, ABS Customised report, Canberra: ABS.

ABS (2020b) National Health Survey, 2017–18, ABS Customised report, Canberra: ABS.

ABS (2022b) 2020–21 NHS: First Results methodology, accessed 10 March 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2012) Risk factors contributing to chronic disease, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2013) Monitoring pulmonary rehabilitation and long-term oxygen therapy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2014) Mortality from asthma and COPD in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2015) Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease–Australian facts: risk factors 2015, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2017) Risk factors to health, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

AIHW (2018) Australia's health 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023. doi:10.25816/5ec1e56f25480.

AIHW (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 May 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023. doi:10.25816/e2v0-gp02.

AIHW (2022b) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Strengthening national COPD monitoring using linked health services data (aihw.gov.au), AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 October 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023c) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

Alison JA, McKeough ZJ, Johnston K, McNamara RJ, Spencer LM, Jenkins SC, Hill CJ, McDonald VM, Frith P, Cafarella P, Brooke M, Cameron-Tucker HL, Candy S, Cecins N, Chan AS, Dale MT, Dowman LM, Granger C, Halloran S, Jung P, Lee AL, Leung R, Matulick T, Osadnik C, Roberts M, Walsh J, Wootton S and Holland AE (2017) ‘Australian and New Zealand Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guidelines’, Respirology, 22(4):800-819, doi:10.1111/resp.13025.

Athanazio R (2012) ‘Airway disease: similarities and differences between asthma, COPD and bronchiectasis’, Clinics, 67(11):1335–1343, doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2012(11)19.

Au DH, Bryson CL, Chien JW, Sun H, Udris EM, Evans LE and Bradley KA (2009) ‘The Effects of Smoking Cessation on the Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations’, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(4):457–463, doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0907-y.

Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA and Bowman BA (2014) ‘Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA’, The Lancet, 384(9937):45–52, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6.

Bhatt SP, Wells JM and Dransfield MT (2014) ‘Cardiovascular disease in COPD: a call for action - The Lancet Respiratory Medicine’, Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 2(10):783–785, doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70197-3.

Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Kinney GL, Washko Jr GR, Budoff M, Kim Y, Bailey WC, Nath H, Hokanson JE, Silverman EK, Crapo J and Dransfield M (2016) ‘β-Blockers are associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations’, Thorax, 71(1):8–14, doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207251.

Britt H, Miller GC, Bayram C, Henderson J, Valenti L, Harrison C, Pan Y, Charles J, Pollack AJ, Chambers T, Gordon J and Wong C (2016) ‘A decade of Australian general practice activity 2006–07 to 2015–16’, General practice series no. 41, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Buist AS (2003) ‘Similarities and differences between asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: treatment and early outcomes’, European Respiratory Journal, 21:30s-35s; doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00404903.

Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gillespie S, Burney P, Mannino DM, Menezes AM, Sullivan SD, Lee TA, Weiss KB, Jensen RL, Marks GB, Gulsvik A and Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E (2007) ‘International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study’, Lancet, 370(9589): 741-750, doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4.

Chatlia WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, Criner GJ and Make BJ (2008) ‘Comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease’, Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 5(4):549–555, doi.org/10.1513/pats.200709-148ET.

DoHAC (2019) National Strategic Action Plan for Lung Conditions, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 31 May 2023.

Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, Zulueta J, Cabrera C, Zagaceta J, Hunninghake G and Celli B (2012) ‘Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease’, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 186(2):155–161. doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC.

Ferrer M, Sellarés J, Valencia M, Carrillo A, Gonzalez G, Badia JR, Nicolas JM and Torres A (2009) ‘Non-invasive ventilation after extubation in hypercapnic patients with chronic respiratory disorders: randomised controlled trial’, Lancet, 374(9695):1082-8, doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61038-2.

Franssen F and Rochester CL (2014) Comorbidities in patients with COPD and pulmonary rehabilitation: do they matter?, European Respiratory Review, 23(131):131–141, doi:10.1183/09059180.00007613.

George M and Bender B (2019) ‘New insights to improve treatment adherence in asthma and COPD’, Patient Prefer Adherence, 13:1325-1334, doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S209532.

GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) (2020) Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2020 Report, GOLD, accessed 31 May 2023.

Gordon CS, Waller JW, Cook RM, Cavalera SL, Lim WT and Osadnik CR (2019) ‘Effect of Pulmonary Rehabilitation on Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, Chest, 156(1):80-91, doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2.

Greenhalgh EM, Bayly M, Scollo MM and Winstanley MH (2023) 1.3 Prevalence of smoking–adults, Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues, Cancer Council Victoria, accessed 31 May 2023.

Hurst JR, Elborn JS and Soyza AD (2015) COPD–bronchiectasis overlap syndrome, European Respiratory Journal, 45(2):310-313, doi:10.1183/09031936.00170014.

Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, Boje Jensen G, Divo M, Faner R, Guerra S, Marott JL, Martinez FD, Martinez-Camblor P, Meek P, Owen CA, Petersen H, Pinto-Plata V, Schnohr P, Sood A, Soriano JB, Tesfaigzi Y and Vestbo J (2015) Lung-Function Trajectories Leading to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, The New England Journal of Medicine, 373(2):111-122, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411532.

Lynch J and Smith GD (2005) A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology, Annual Review Public Health, 26:1-35, doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505.

McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E and Lacasse Y (2015) Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2):CD003793, doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD00379.

Mosenifar Z (2022) Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Treatment & Management. Medscape, accessed 31 May 2023.

Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson-Chahhoud KV, Picot J, Wedzicha JA and Smith BJ (2017) Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7):CD004104, doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub4.

Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates CJ and Troosters T (2016) Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12):CD005305, doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub4.

Ram FS, Picot J, Lightowler J and Wedzicha JA (2004) Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for treatment of respiratory failure due to exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Cochrane Database Systematic Review, (1):CD004104, doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004104.pub3.

Reed RM, Eberlein M, Girgis RE, Hashmi S, Iacono A, Jones S, Netzer G and Scharf S (2012) Coronary artery disease is under-diagnosed and under-treated in advanced lung disease, American Journal of Medicine, 125(12):1228.e13–1228e.22, doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.05.018.

RACGP (Royal Australian College of General Practice) (2021) Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals, RACGP, accessed 1 May 2023.

Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, Hill K, Holland AE, Lareau SC, Man WD, Pitta F, Sewell L, Raskin J, Bourbeau J, Crouch R, Franssen FM, Casaburi R, Vercoulen JH, Vogiatzis I, Gosselink R, Clini EM, Effing TW, Maltais F, van der Palen J, Troosters T, Janssen DJ, Collins E, Garcia-Aymerich J, Brooks D, Fahy BF, Puhan MA, Hoogendoorn M, Garrod R, Schols AM, Carlin B, Benzo R, Meek P, Morgan M, Rutten-van Mölken MP, Ries AL, Make B, Goldstein RS, Dowson CA, Brozek JL, Donner CF and Wouters EFM (2013) An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 188(8):e13-64, doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014) The Health Consequences of Smoking–50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General Executive Summary, CDC website, accessed 3 March 2020.

Van der Molen T (2010) Co-morbidities of COPD in primary care: frequency, relation to COPD, and treatment consequences, Primary Care Respiratory Journal, 19(4):326–334, doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2010.00053.

WHO (World Health Organisation) (2023) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), WHO website, accessed 31 May 2023.

Yang IA, Dabscheck EJ, George J, Jenkins SC, McDonald CF, McDonald VM, Smith BJ, and Zwar NA (2019) COPD-X Concise Guide, Lung Foundation Australia and Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand, Brisbane.

Yang IA, George J, McDonald CF, McDonald V, O’Brien M, Craig S, Smith B, McNamara R, Zwar N and Dabscheck E (2022) 'P1.1 Smoking cessation', The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2022, Version 2.68, Lung Foundation Australia.