Peripheral arterial disease

Page highlights:

How many Australians have peripheral arterial disease?

- Peripheral arterial disease has been estimated to affect up to 10% of patients in primary care settings, and over 20% when studied in populations aged 75 and over.

- In 2020–21, there were around 59,100 hospitalisations where peripheral arterial disease was recorded.

- The age-standardised rate of hospitalisations of peripheral arterial disease declined by 47% between 2000–01 and 2020–21.

Peripheral arterial disease was the underlying cause of 1,900 deaths in 2021 — equating to 1.1% of all deaths.

Peripheral arterial disease was the underlying cause of 1,900 deaths in 2021 — equating to 1.1% of all deaths.

What is peripheral arterial disease?

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD), also known as peripheral vascular disease, is the reduced circulation of blood to a body part outside of the heart or brain.

PAD occurs most commonly in the arteries leading to the legs and feet. It is often the result of atherosclerosis, where fatty deposits build up in the walls of arteries. In some people it does not present any symptoms, while others may experience pain at rest or while walking. In severe cases it can lead to tissue loss, and the amputation of a limb.

A notable form of PAD is abdominal aortic aneurysm. This is abnormal widening of the aorta (the main artery leading from the heart) below the level of the diaphragm. It can be a life-threatening condition if the arterial wall ruptures. Surgery is necessary in some cases.

Tobacco smoking and diabetes are primary risk factors for PAD. Type 2 diabetes in people with PAD can accelerate atherosclerosis, and increase the risk of amputation, of other cardiac events such as stroke, and death.

Other PAD risk factors include abnormal blood lipids, high blood pressure, overweight or obesity, and family history of the disease. PAD has increasingly been associated with other chronic conditions such as atrial fibrillation, heart failure, obstructive sleep apnoea and chronic kidney disease.

How many Australians have peripheral arterial disease?

Currently, there are no national data on the number of Australians living with PAD.

PAD has been estimated to affect up to 10% of patients in primary care settings, and over 20% when studied in populations aged 75 and over (Aitken 2020, Conte & Vale 2018). Over half of all people with PAD show no symptoms, leading to under-diagnosis and under-treatment.

Hospitalisations

Peripheral arterial disease often occurs alongside other chronic diseases, so both the principal and additional diagnoses of PAD should be counted when estimating its contribution to hospitalisations.

There were around 59,100 hospitalisations where PAD was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21, at a rate of 230 per 100,000 population. This represents 0.5% of all hospitalisations in Australia.

PAD was recorded as the principal diagnosis in 56% (33,200) of these hospitalisations.

Over half of all hospitalisations where PAD was the principal diagnosis (60%) were for atherosclerosis of the peripheral arteries, while abdominal aortic aneurysm accounted for a further 9%. The remainder was comprised largely of embolisms and other aneurysms.

Age and sex

Where PAD was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, hospitalisation rates:

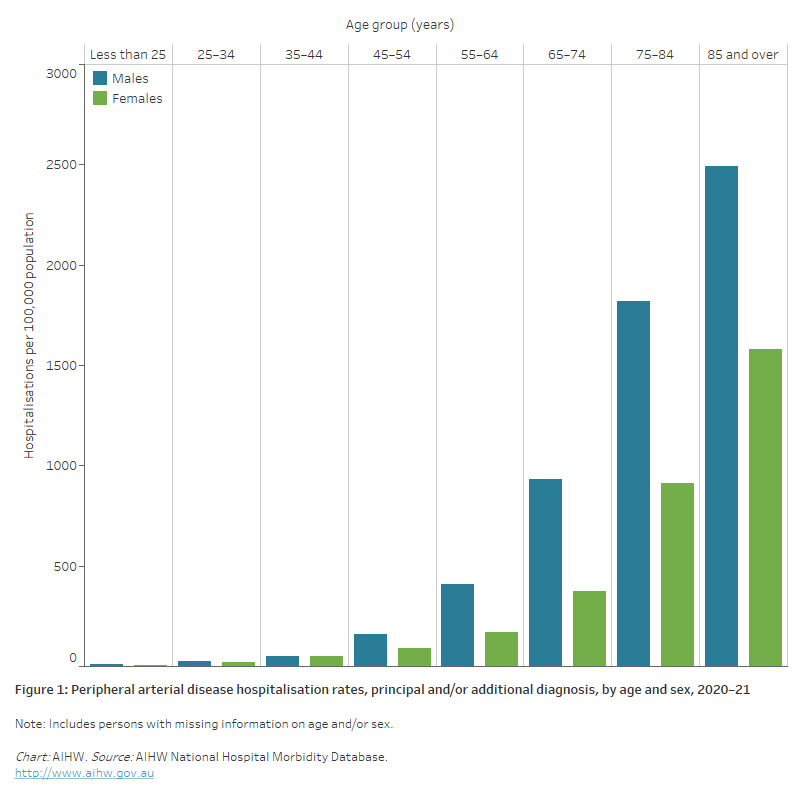

- were overall twice as high for males as females, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher among males than females in all age groups, except for age 35–44

- increased with age, with rates highest for males and females aged 85 and over – at least 1.4 times as high as those aged 75–84 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Peripheral arterial disease hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows in 2020–21, peripheral arterial disease hospitalisation rates were highest among males and females aged 85 and over (2,500 and 1,600 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Trends

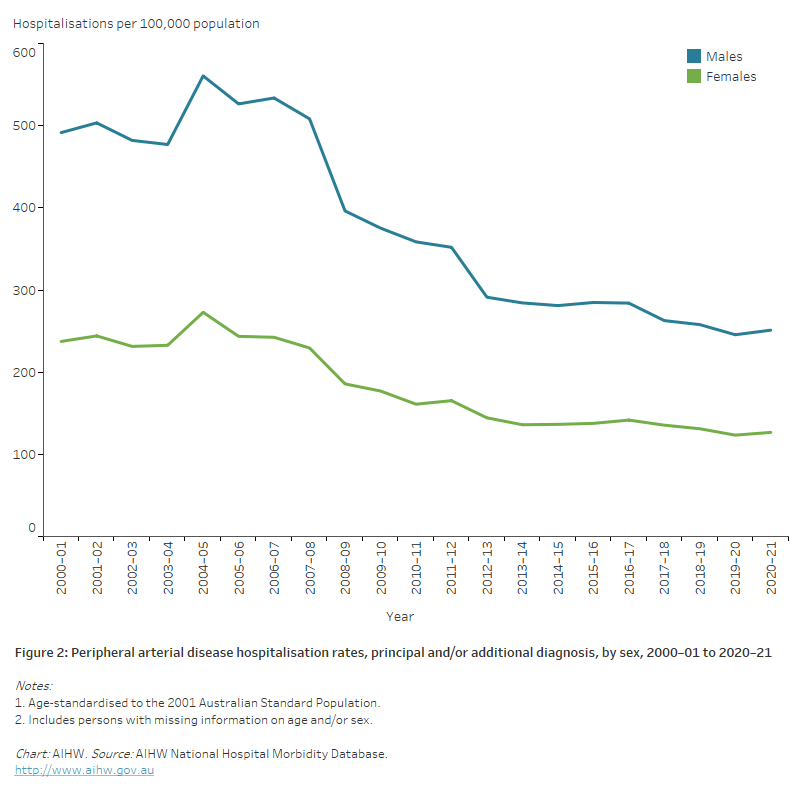

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, the age-standardised rate of hospitalisations with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of PAD declined by almost half (47%) — from 350 to 185 per 100,000 population.

The number of PAD hospitalisations declined by 8% for males and 15% for females, while rates fell by 49% for males and 47% for females (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Peripheral arterial disease hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows that age-standardised peripheral arterial disease hospitalisation rates declined between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 492 to 251 and 237 to 127 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively.

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were 1,453 hospitalisations with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of PAD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – a rate of 167 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

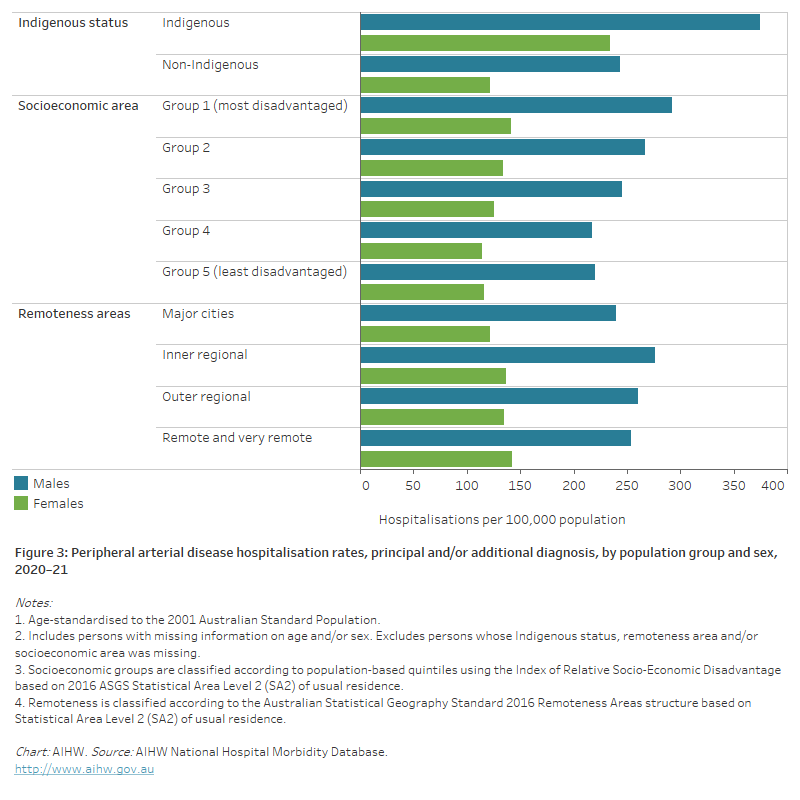

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 1.7 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate

- the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was greater for females than males — 1.9 times as high for females and 1.5 times as high for males (Figure 3).

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, age-standardised PAD hospitalisation rates were 1.3 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas.

For males, the rate of PAD hospitalisations among people living in lowest socioeconomic areas was 1.3 times as high as in the highest socioeconomic areas, and for females 1.2 times as high (Figure 3).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, age-standardised PAD hospitalisation rates among those living in Remote and very remote areas were similar to those in Major cities (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Peripheral arterial disease hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows that age-standardised peripheral arterial disease hospitalisation rates in 2020–21 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas and people living in Remote and very remote areas.

Deaths

PAD was the underlying cause of 1,900 deaths in 2021, at a rate of 7.4 per 100,000 population — equating to 1.1% of all deaths, and 4.5% of all cardiovascular disease deaths.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm accounted for 24% of PAD deaths with the remainder resulting from atherosclerosis of peripheral arteries, other aneurysms, embolisms and unspecified PAD.

Leading causes of death in people diagnosed with PAD, however, were chronic ischaemic heart disease (13%), acute myocardial infarction (7.9%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (7.9%).

Age and sex

In 2021, PAD death rates:

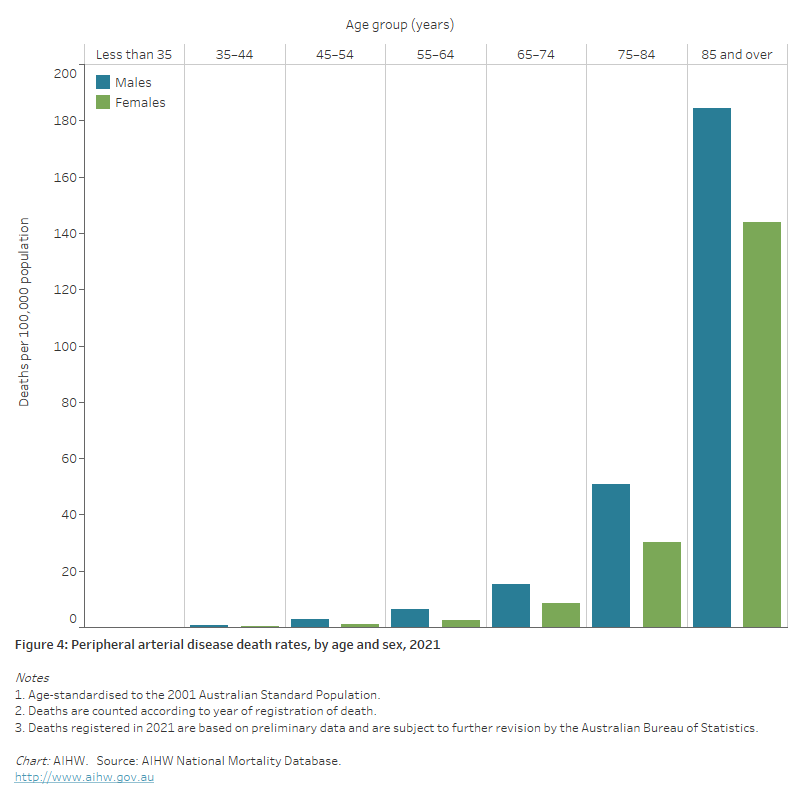

- were 1.2 times as high for males as for females, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates for males were higher than for females across all age groups

- increased with age, with three-quarters (73%) of PAD deaths occurring in persons aged 75 and over. PAD death rates for males and females were highest in the 85 and over age group—3.6 times as high for males and 4.7 times as high for females aged 75–84 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Peripheral arterial disease death rates, by age and sex, 2021

The bar chart shows the age-standardised peripheral arterial disease death rates in 2021 were highest among males and females aged 85 and over (184 and 144 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Trends

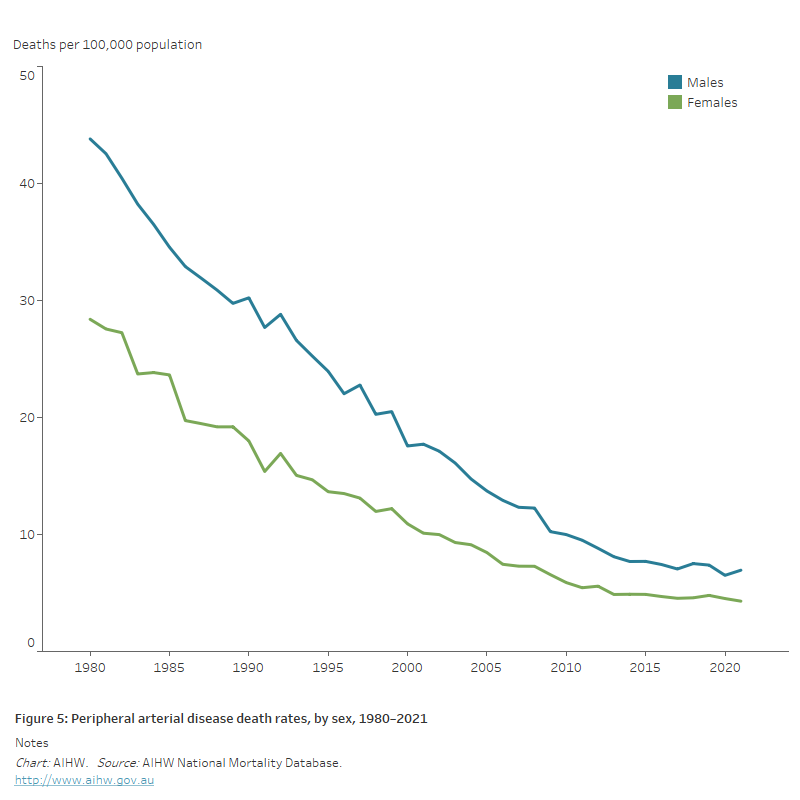

Between 1980 and 2021:

- the annual number of PAD deaths declined by almost 40%, from 3,100 to 1,900

- age-standardised PAD death rates declined by over 80% — falling from 44 to 6.9 per 100,000 population for males and 28 to 4.3 per 100,000 for females (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Peripheral arterial disease death rates, by sex, 1980–2021

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised peripheral arterial disease death rates between 1980 and 2021 for both males and females, from 44 to 6.9 and 28 to 4.3 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Variation among population groups

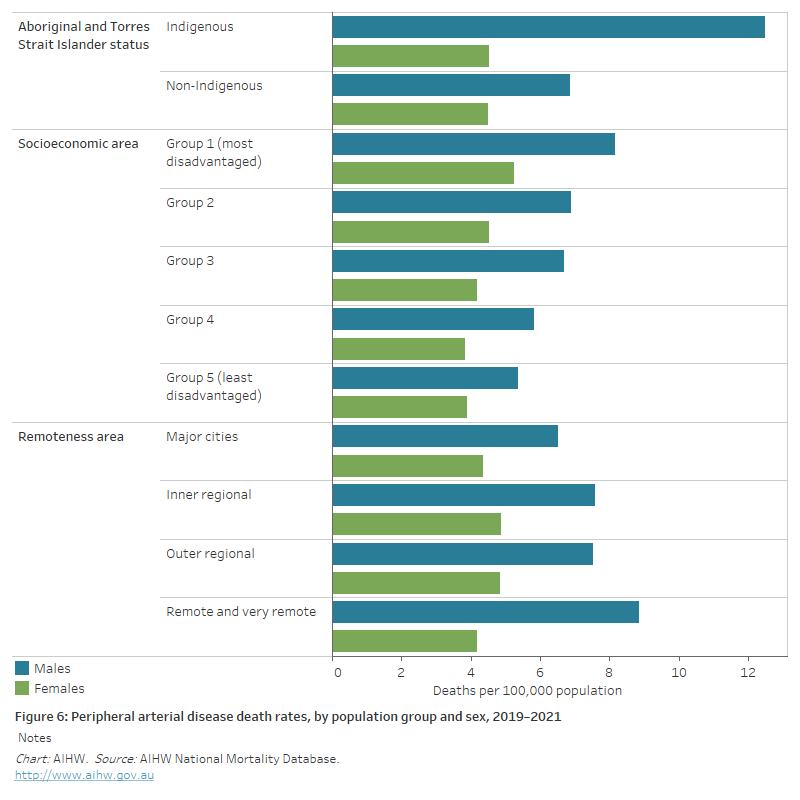

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2019–2021, there were 74 deaths from PAD as an underlying cause among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in jurisdictions with adequate Indigenous identification, a rate of 3.2 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the rate of death from PAD for Indigenous Australians was 1.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous males had PAD death rates 1.8 times as high as non-Indigenous males and Indigenous females 1.0 times as high (Figure 6).

Socioeconomic area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised PAD death rate was 1.4 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The difference was similar for males and females (1.5 times and 1.4 times as high) (Figure 6).

Remoteness area

In 2019–2021, the age-standardised PAD death rate was 1.2 times as high in Remote and very remote areas compared with Major cities.

The male rate in Remote and very remote areas was 1.4 times as high as that in Major cities. The female rate was slightly higher in Major cities compared to Remote and very remote areas (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Peripheral arterial disease death rates, by population group and sex, 2019–2021

The horizontal bar chart shows in 2019–2021 age-standardised peripheral arterial disease death rates were higher among Indigenous Australians and people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas but did not differ significantly by remoteness area.

References

Aitken SJ (2020) Peripheral artery disease in the lower limbs. Australian Journal of General Practice 49: 239–44.

Conte SM & Vale PR (2018) Peripheral arterial disease. Heart, Lung and Circulation 27: 427–432.