Coronary heart disease

Page highlights:

How many Australians have coronary heart disease?

- In 2017–18, an estimated 580,000 Australians aged 18 and over (3.1% of the adult population) had coronary heart disease at some time in their lives.

- The rate of coronary heart disease among Indigenous adults was more than twice that of non-Indigenous adults.

- In 2020, there were an estimated 56,700 acute coronary events among people aged 25 and over–equivalent to around 155 events every day.

- In 2020–21, there were 160,000 hospitalisations where coronary heart disease was recorded as the principal diagnosis, equivalent to 1.4% of all hospitalisations, and 27% of all cardiovascular disease hospitalisations in Australia.

In 2021, coronary heart disease was the underlying cause of 17,300 deaths (10% of all deaths).

In 2021, coronary heart disease was the underlying cause of 17,300 deaths (10% of all deaths).

Coronary heart disease (CHD), also known as ischaemic heart disease, is the most common cardiovascular disease. There are 2 main clinical forms – heart attack and angina.

![]()

Heart attack – or acute myocardial infarction (AMI) – is a life-threatening event that occurs when a blood vessel supplying the heart is suddenly blocked, threatening to damage the heart muscle and its functions. STEMI (ST segment elevation myocardial infarction) is the most serious type of heart attack. It is almost always caused by a complete blockage of a major coronary artery, leading to a long interruption of blood supply. NSTEMI (Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction) is characterised by a partially blocked artery, which severely reduces blood flow.

Angina is chest pain caused by reduced blood flow to the heart. With stable angina, periodic episodes of chest pain occur when the heart has a temporary deficiency in blood supply. Unstable angina is an accelerating pattern of chest discomfort, and is the more dangerous form due to a changing severity in partial coronary artery blockages. It is treated in a similar manner to heart attack.

Both heart attack and unstable angina are sudden, severe life-threatening events. They are part of a continuum of acute coronary heart diseases, and are together described as acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

How many Australians have coronary heart disease?

An estimated 580,000 Australians aged 18 and over (3.1% of the adult population) had CHD at some time in their lives, based on self-reported data from the ABS 2017–18 National Health Survey (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019).

Of those with CHD, 227,000 had experienced angina while 430,000 had a heart attack or another form of CHD, noting that a person may report more than 1 disease.

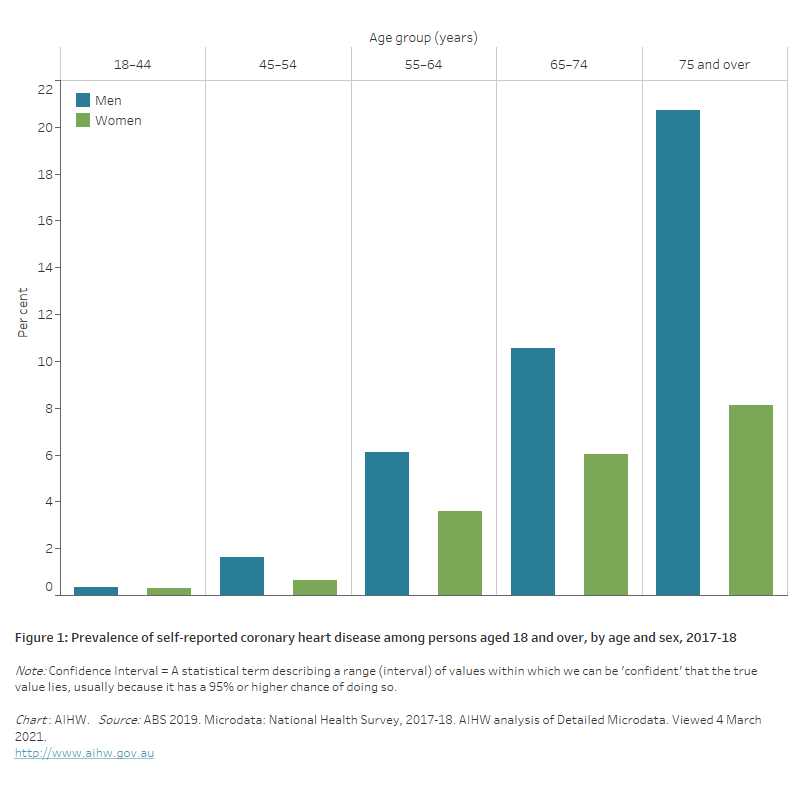

Age and sex

- After adjusting for age, a higher percentage of men (3.8%) than women (1.9%) were estimated to have CHD in 2017–18.

- CHD occurred more commonly in older age groups, increasing from 1.1% in those aged 45–54 to 14% among those aged 75 and over.

- At age 75 and over, there is a marked difference between men (21%) and women (8.1%) reporting having CHD (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease among persons aged 18 and over, by age and sex, 2017–18

The bar chart shows the prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease by age group in 2017–18. Rates were highest among men and women aged 75 and over (21% and 8.1%).

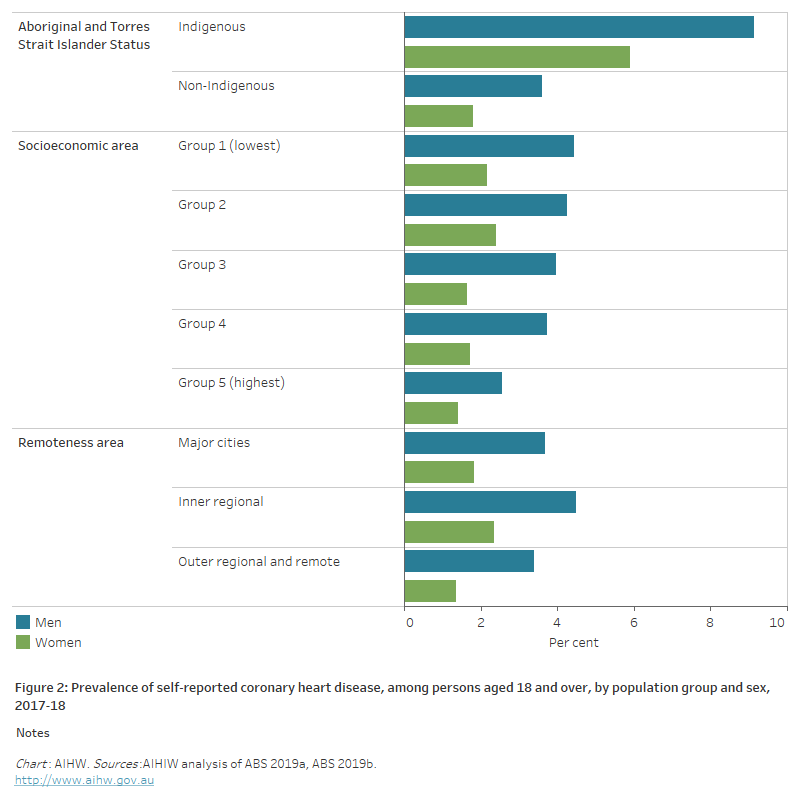

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

An estimated 27,400 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults (5.6%) had CHD, based on self-reported data from the ABS 2018–19 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019b).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the rate of CHD among Indigenous adults was 2.7 times that of non-Indigenous adults.

Indigenous men were 2.5 times as likely to report having CHD as non-Indigenous men, and Indigenous women 3.3 times as likely as non-Indigenous women (Figure 2).

Socioeconomic area

In 2017–18, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, adults living in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged areas were 1.6 times as likely to report having CHD compared with those in the least disadvantaged areas (Figure 2).

Rates were significantly higher for men than women, except for those living in the least disadvantaged areas.

Remoteness area

In 2017–18, the prevalence of CHD among adults, based on self-reported data, did not vary significantly by remoteness area (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease, among persons aged 18 and over, by population group and sex, 2017–18

The horizontal bar chart shows that the prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease in 2017–18 was higher among Indigenous Australians and people living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, but did not vary significantly by remoteness areas.

Acute coronary events

There are no direct national data sources on the number of new cases (incidence) of CHD each year. However, a related measure can be used as an estimate – the number of acute coronary events (including heart attack and unstable angina) –developed by the AIHW using unlinked hospital and deaths data (AIHW 2014, 2022).

In 2020, there were an estimated 56,700 acute coronary events among people aged 25 and over – equivalent to around 155 events every day. Around 12% of these events (6,900 cases) were fatal.

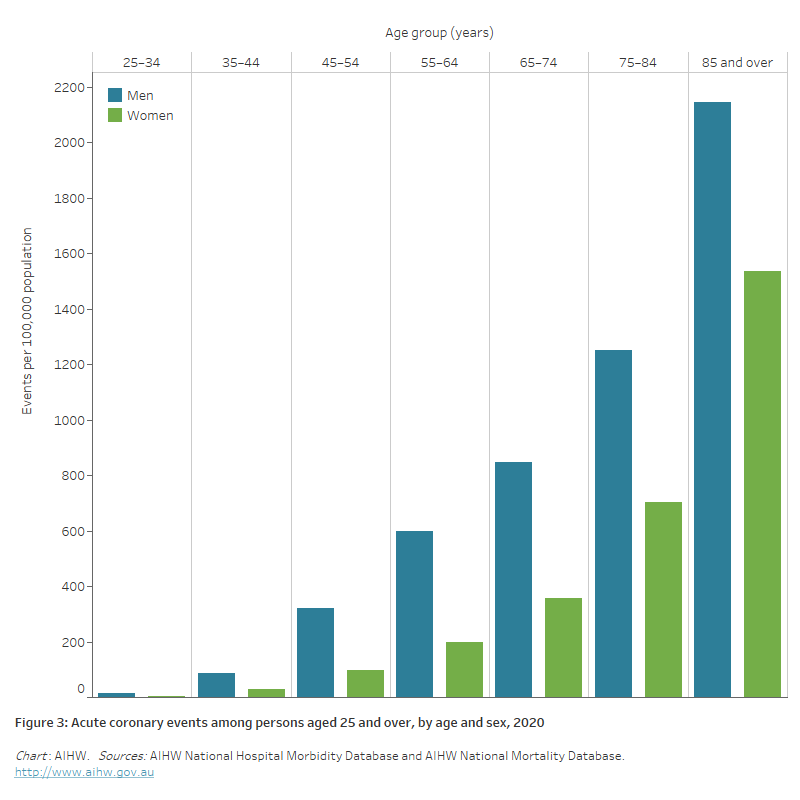

Age and sex

In 2020, an estimated two-thirds (66%) of acute coronary events among persons aged 25 and over occurred in men.

Rates of acute coronary events:

- were 2.3 times as high in men than women, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations

- increased with age, with the rate among the 85 and over age group almost 3 times the rate of the 65–74 age group and 4 times the rate for the 55–64 year old age group (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Acute coronary events among persons aged 25 and over, by age and sex, 2020

The bar chart shows rates of acute coronary events by age group in 2020. These were highest among men and women aged 85 and over (2,100 and 1,500 per 100,000 population).

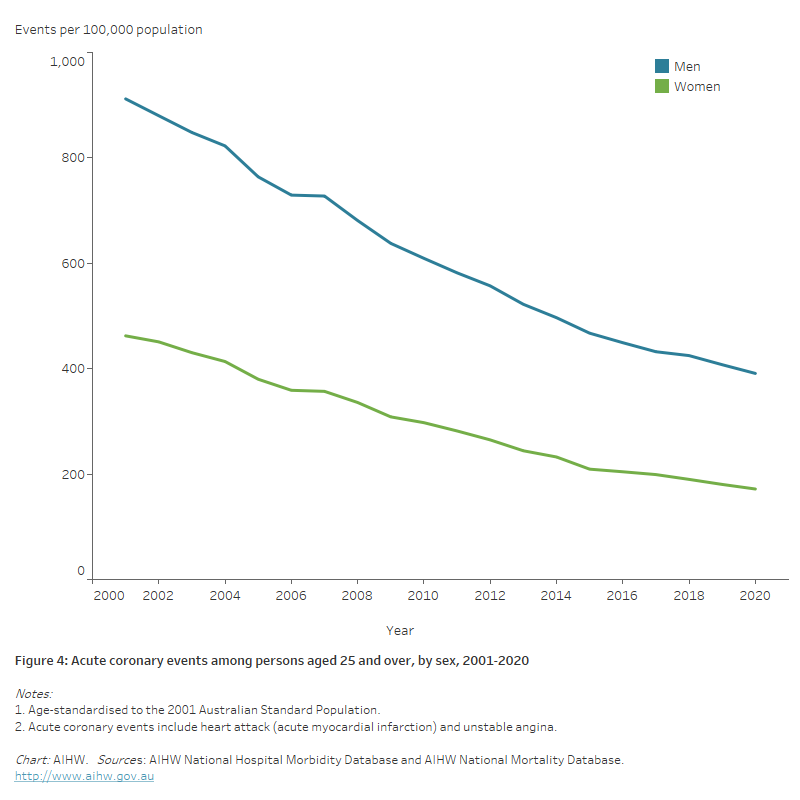

Trends

The age-standardised rate of acute coronary events fell by more than half (59%) between 2001 and 2020 (675 to 277 per 100,000 population). The decline was slightly higher for women (63%) than men (57%) (Figure 4).

The decline in rates of acute coronary events has been attributed to a number of factors, including improvements in medical and surgical treatment, and the increased use of antithrombotic drugs as well as drugs to lower blood pressure and cholesterol. Reductions in risk factor levels – including tobacco smoking, high blood cholesterol and high blood pressure–have also contributed to these declines (Taylor et al. 2006).

Figure 4: Acute coronary events among persons aged 25 and over, by sex, 2001–2020

The line chart shows declines in age-standardised rates of acute coronary events between 2001 and 2020, from 912 to 391 per 100,000 population for men aged 25 and over, and from 462 to 172 for women.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 25 and over experienced an estimated 2,200 acute coronary events in 2020.

Rates of acute coronary events among Indigenous people were higher than among non-Indigenous Australians – 2.9 times as high in 2020, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations.

The rate of acute coronary events among younger Indigenous people is many times that of younger non-Indigenous people (AIHW 2015).

Hospitalisations

In 2020–21 there were 160,000 hospitalisations where CHD was recorded as the principal diagnosis, equivalent to 1.4% of all hospitalisations, and 27% of all CVD hospitalisations in Australia.

Of these, angina accounted for 22% (35,300 hospitalisations) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) for 36% (57,100 hospitalisations).

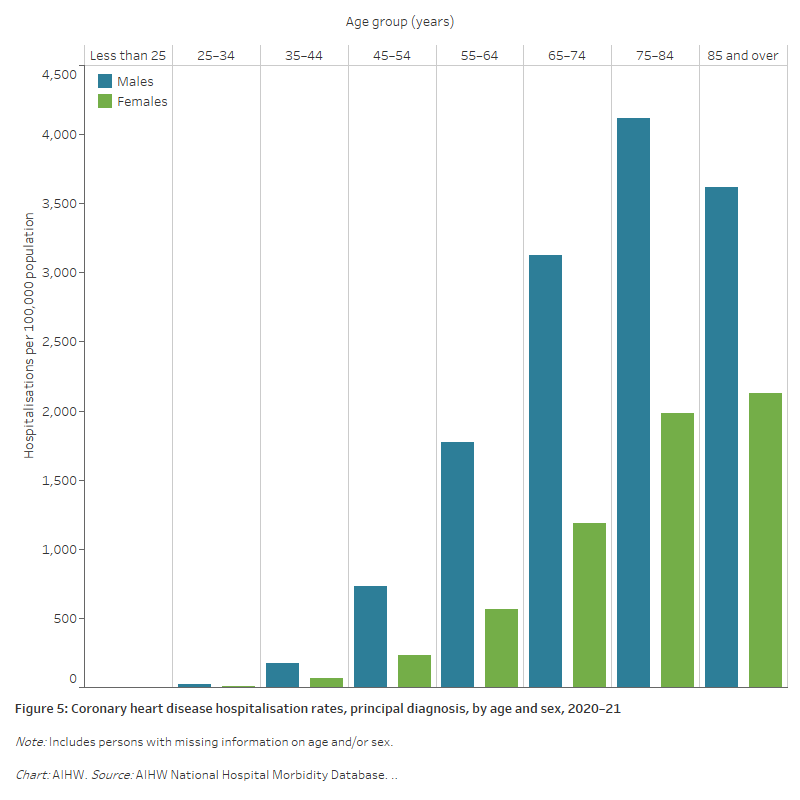

Age and sex

In 2020–21, CHD hospitalisation rates as the principal diagnosis:

- were overall 2.5 times as high for males as females after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations. Age-specific rates were higher among males than females across all age groups (Figure 5)

- increased to age 75–84, with two-thirds (65%) of CHD hospitalisations occurring in those aged 65 and over. CHD hospitalisation rates for males were highest in the 75–84 age group (4,100 per 100,000 population) and for females in the 85 and over age group (2,100 per 100,000 population).

Figure 5: Coronary heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows coronary heart disease hospitalisation rates by age group in 2020–21. Rates were highest among males aged 75–84 (4,100 per 100,000 population) and females aged 85 and over (2,100 per 100,000 population).

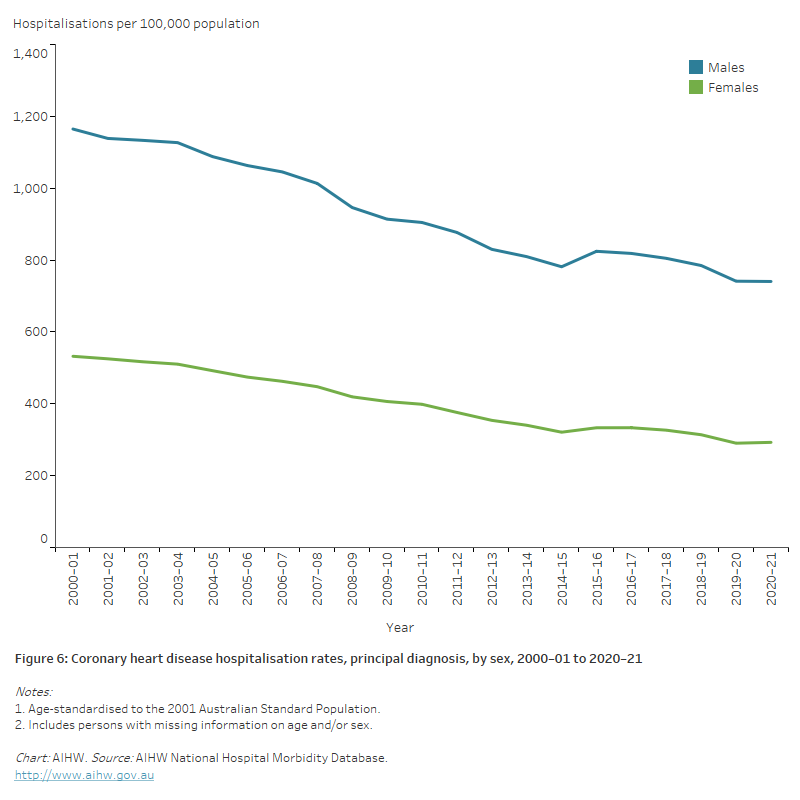

Trends

After adjusting for different population age structures over time, there was a 39% reduction in the rate of hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of CHD between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 833 to 508 per 100,000 population.

The annual number of CHD hospitalisations increased by 7.4% for males and fell by 10.9% for females, while the rate of CHD hospitalisation fell by 45% for females and 36% for males (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Coronary heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by sex, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised rates of coronary heart disease hospitalisations between 2000–01 and 2020–21, from 1,165 to 740 per 100,000 population for males, and from 532 to 293 for females.

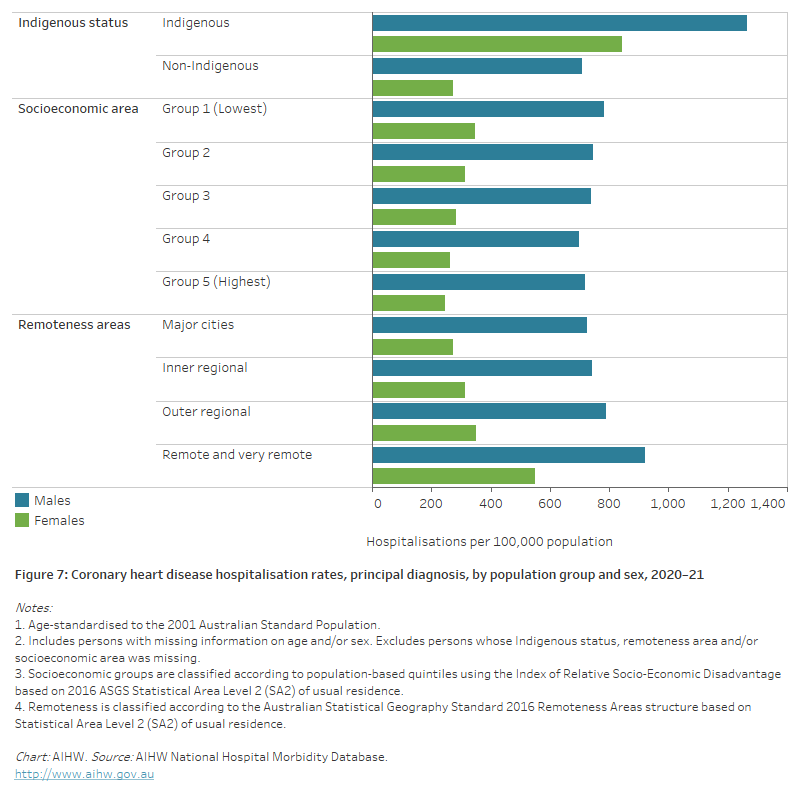

Variation among population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 5,400 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of CHD among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, a rate of 623 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations:

- the rate among Indigenous Australians was 2.1 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate

- the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was greater for females than males – 3.1 times as high for females and 1.8 times as high for males (Figure 7).

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, CHD hospitalisation rates were 1.2 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those in the highest socioeconomic areas.

The disparity was greater for females than males (1.4 and 1.1 times as high, respectively) (Figure 7).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, CHD hospitalisation rates were around 1.5 times as high among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those in Major cities.

This largely reflects disparities in female rates, which were twice as high in Remote and very remote areas as in Major cities – while male rates were 1.3 times as high (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Coronary heart disease hospitalisation rates, principal diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The horizontal bar chart shows that male and female coronary heart disease hospitalisation rates in 2020–21 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas, and people living in remote and very remote areas.

Deaths

In 2021, coronary heart disease (CHD) was the underlying cause of 17,300 deaths, at a rate of 68 per 100,000 population. CHD was the leading single cause of death in Australia in 2021, equivalent to 10% of all deaths and 41% of all CVD deaths.

Almost 2 in 5 (38%) CHD deaths (6,500) resulted from acute myocardial infarction (AMI, or heart attack).

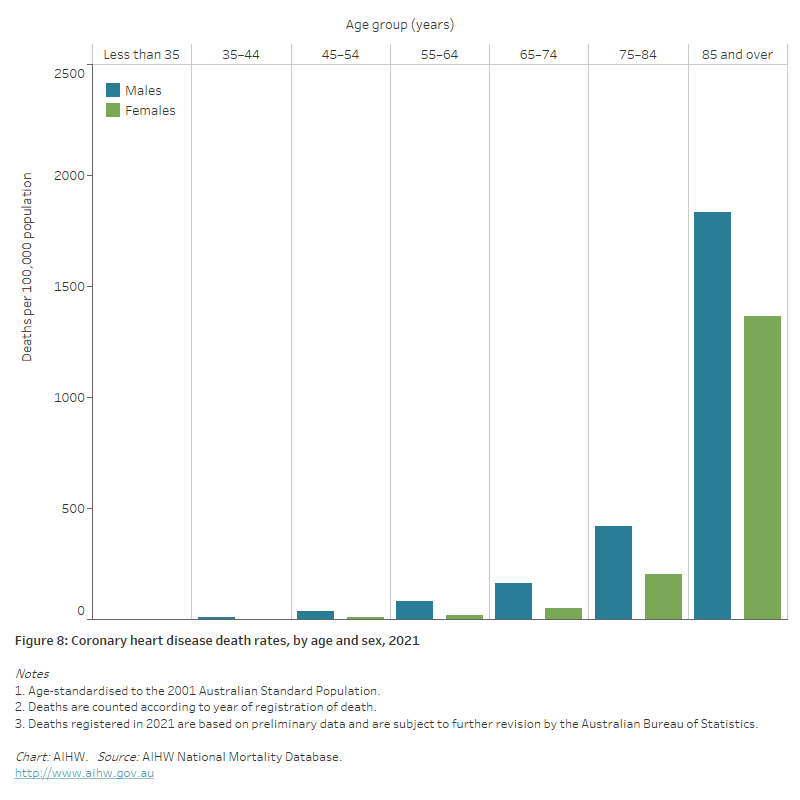

Age and sex

In 2021:

- after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, CHD death rates were twice as high for males as for females

- CHD death rates increased with age, with around half of all CHD deaths (48%) occurring in persons aged 85 and over. CHD death rates for males and females were highest in the 85 and over age group – 4 times as high for males and 7 times as high for females aged 75–84 (Figure 8)

- CHD was responsible for a large proportion of premature deaths before age 75, especially in the male population – 37% of males dying from CHD were aged less than 75 years, compared with 15% of females.

Figure 8: Coronary heart disease death rates, by age and sex, 2021

The bar chart shows coronary heart disease death rates by age groups in 2019. Rates were highest among men and women aged 85 and over (1,926 and 1,462 per 100,000 population).

Trends

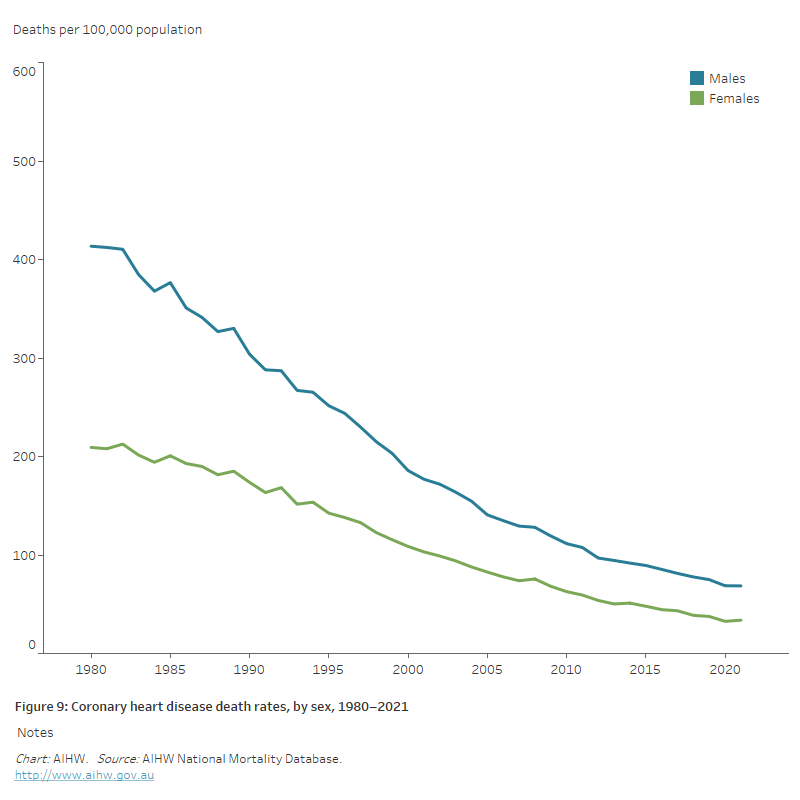

CHD death rates have been declining in Australia since the late 1960s. Between 1980 and 2021:

- the number of CHD deaths declined by 44%, from 31,000 to 17,300

- age-standardised CHD death rates declined substantially, by more than 80% – falling from 414 to 69 per 100,000 population for males, and 209 to 34 per 100,000 population for females (Figure 9).

Much of the decline in CHD mortality in Australia over recent decades can be attributed to reductions in levels of population risk factors, including tobacco smoking, abnormal blood lipids and high blood pressure.

Declines in CHD mortality can also be attributed to improvements in medical and surgical treatment. Better emergency care, the use of statins and agents to lower blood pressure and anti-platelet drugs, along with revascularisation procedures, have each contributed to better CHD outcomes, both in and out of hospital.

Evidence from a number of countries attributes lower CHD death rates to improvements in risk factors levels and to better treatment in about equal proportion (AIHW 2017).

Provisional mortality data

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) provisional mortality statistics indicate that there were 13,700 doctor-certified deaths due to CHD during 2020, rising to 14,100 in 2021 and 14,900 in 2022 (ABS 2023).

CHD mortality continued its historical decline in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, but has since increased – the number of deaths in 2022 being 9.1% higher than the number in 2020.

Note that these data are preliminary, with some deaths that occurred in 2022 not yet registered. In addition, causes of death were not presented for coroner-referred deaths due to the time required to complete coronial investigations (ABS 2023).

Figure 9: Coronary heart disease death rates, by sex, 1980–2021

The line chart shows the decline in age-standardised coronary heart disease death rates between 1980 and 2019, from 414 to 73 per 100,000 population for males and from 209 to 37 for females.

Variation among population groups

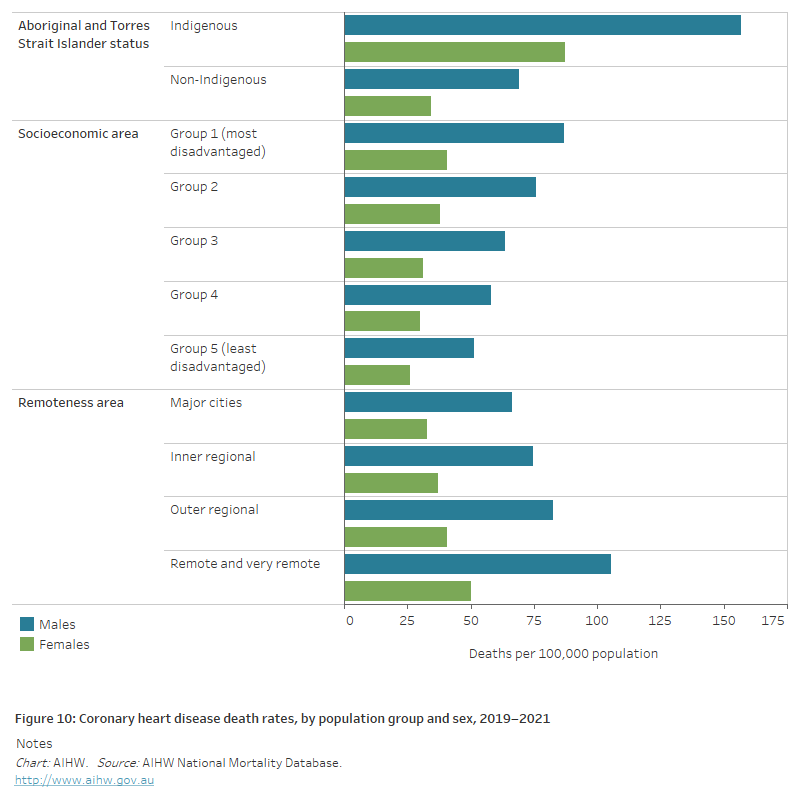

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

CHD is the leading cause of death in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.

In 2019–2021:

- CHD was the underlying cause of death for 1,197 Indigenous people in jurisdictions with adequate Indigenous identification, a rate of 53 per 100,000 population.

- After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the CHD death rate for Indigenous Australians was 2.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians .

- CHD death rates for Indigenous males and females were 2.3 and 2.5 times as high as for non-Indigenous males and females (Figure 10).

Socioeconomic area

- In 2019–2021, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations , the CHD death rate was 1.7 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas.

- The difference was similar among males and females (1.7 and 1.6 times as high) (Figure 10).

Remoteness area

- In 2019–2021, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations , the CHD death rate was 1.6 times as high in Remote and very remote areas compared with Major cities.

- The male CHD death rate in Remote and very remote areas was 1.6 times as high as in Major cities, and the female rate 1.5 times as high (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Coronary heart disease rates, by population group and sex, 2019–2021

The horizontal bar chart shows that coronary heart disease death rates in 2017–2019 were higher among Indigenous Australians, people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas, and people living in remote and very remote areas.

ABS 2019a. Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18. AIHW analysis of Detailed Microdata. Viewed 4 March 2021.

ABS 2019b. Microdata: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2017–18. AIHW analysis of Detailed Microdata. Viewed 4 March 2021.

ABS (2023) Provisional Mortality Statistics, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 31 March 2023.

AIHW 2014. Acute coronary syndrome: validation of the method used to monitor incidence in Australia. Cat. no. CVD 68. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2015. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease—Australian facts: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Cat. no. CDK 5. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2017. Trends in cardiovascular deaths. Cat. no. AUS 216. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW 2022. Validating algorithms for incidence of cardiovascular disease: Technical Report. Cat. No. CDK 22. Canberra: AIHW.

Taylor R, Dobson A & Mirzaei M 2006. Contribution of changes in risk factors to the decline of coronary heart disease mortality in Australia over three decades. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 13: 760–8.