Health service use

On this page:

DVA provides services to support permanent, reserve and ex-serving ADF members during and after ADF service. Veterans may use these services, or those available to all Australians through mainstream providers.

DVA funds health-related services and programs where clinically required for eligible veterans and their families (those with a DVA-issued health card). DVA funding of health care for entitled veterans is ‘demand driven and uncapped’ – this means that the Australian Government increases health care funding if needed (DVA 2018).

Medicines

The Australian Government subsidises many medications. All Australian residents who hold a current Medicare card can access medications listed under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), subject to patient entitlement status. The Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), funded by DVA, subsidises medications listed under the PBS and additional medications and items for eligible veterans, war widows/widowers, and their dependants.

In 2017–18, more than 1 million medications were dispensed under the PBS/RPBS to around 70,000 ex-serving ADF members with service between 1 January 2001 and 1 July 2017. This was an average of 16 medications dispensed per person (AIHW 2019).

After accounting for age and sex differences, similar proportions of the ex-serving and Australian populations were dispensed medications in 2017–18 (72% and 71%, respectively) (AIHW 2019). Among ex-serving ADF members:

- 37% were dispensed at least 1 nervous system medication (including antidepressants and anxiolytics) – compared with 31% for all Australians.

- 22% were dispensed at least one cardiovascular system medication (for example for hypertension or high cholesterol) – compared with 24% for all Australians.

Policies regarding mental health treatment for ex-serving ADF members have undergone change in recent years to facilitate early access to mental health treatment. The full effect of these changes may not be reflected for the ex-serving ADF members captured in this data. Due to these policies, ex-serving ADF members have different pricing structures for, and access to, medications from the Australian population. These factors may influence the levels of dispensing between ex-serving members and the Australian population.

Almost 1 in 6 (17%) of the ex-serving ADF population were dispensed at least 1 antidepressant in 2017–18 (AIHW 2019). After accounting for differences in the age and sex structures of the populations, 20% of all ex-serving ADF members received at least 1 dispensing for antidepressants, compared with 15% in the Australian population. On average, ex-serving ADF members who received at least 1 dispensing for antidepressants, received 9 dispensing per person, similar to the Australian population (AIHW 2020).

More information is available in the report Medications dispensed to contemporary ex-serving Australian Defence Force members, 2017–18.

Hospitalisations

Defence funds all hospital care for permanent and reserve ADF members while DVA funds hospital care for eligible ex-serving ADF members and eligible dependants.

Data are available for public and private hospitalisations by source of funding, which allows the identification of hospitalisations where the cost of care was funded by DVA or Defence. Individuals are asked on presentation at a hospital if they are a DVA or Defence eligible patient and are referred to as a compensable patient. However, the eligibility to receive hospital treatment as a DVA compensable patient may not necessarily have been confirmed by DVA.

In 2019–20, data from the National Hospitals Morbidity Database (NHMD) shows:

- Around 10,700 hospitalisations were funded by Defence, and 200,600 were funded by DVA. Combined, this represented 1.9% of all hospitalisations (AIHW 2021a).

- DVA- and Defence-funded hospitalisations occurred most frequently in private hospitals (71% of DVA-funded hospitalisations and 82% of Defence-funded hospitalisations). For all other Australian hospitalisations, 39% were in private hospitals (AIHW 2021a).

- DVA-funded hospitalisations have been declining since 2015–16 (by 5.1% on average each year before COVID-19), while total hospitalisations in Australia have indicated a consistent upward trend (by 2.9% on average per year before COVID-19), except for 2019–20 where the number of hospitalisations decreased by 2.8% compared with 2018–19 (AIHW 2021a). The decrease in the number of hospitalisations was due to the impacts that COVID-19 had on the hospital system, including restrictions on some types of hospital services.

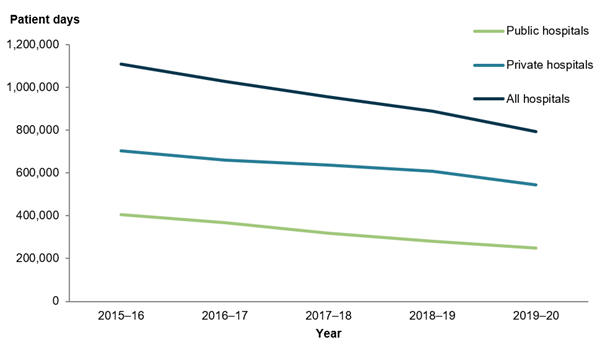

Between 2015–16 and 2019–20, DVA patient days1 decreased by 8.0% on average each year (decreasing by 11% in public hospitals and 6.2% in private hospitals; Figure 12). This is likely attributable to the declining number of funded DVA hospitalisations which may be confounded by the declining number of the older DVA Gold Card population and increasing number of younger DVA White Card population (DVA 2021). In comparison, patient days across all Australian funding sources2 has remained relatively stable over the same period (increased by 0.5% in public hospitals, increased by 0.3% in private hospitals, and overall increased by 0.4% on average each year) (AIHW 2021a).

Figure 12: Department of Veterans’ Affairs hospital patient days, 2015–16 to 2019–20

Note: Appendix information with notes on definitions and data limitations is available to download at Hospitals info and downloads – About the data.

Chart: AIHW.

Source: AIHW (2021) Admitted patient care 2019–20 7: Costing and funding, Table S7.2. See Health of veterans: supplementary data tables – S7.

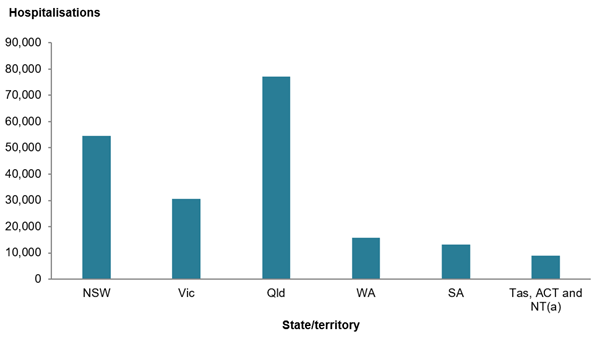

In 2019–20, around 201,000 hospitalisations were funded by DVA, with most of these occurring in Queensland (38%) and New South Wales (27%) (AIHW 2021a) (Figure 13), aligning with the states where the majority of DVA clients are located (DVA 2021).

Figure 13: Department of Veterans’ Affairs-funded hospitalisations, by states and territories, 2019–20

(a) Data for private hospital separations for Tasmania, ACT and NT are not reported individually in the source data. Figure is calculated from the difference between total amount and other states and territories.

Note: Appendix information with notes on definitions and data limitations is available to download at Hospitals info and downloads – About the data.

Chart: AIHW.

Source: AIHW (2021) Admitted patient care 2019-20 7: Costing and funding, Table S7.3. See Health of veterans: supplementary data tables – S8.

More information is available in the report Hospitals – Admitted patient care 2019–20.

Health expenditure

The Australian Government funds DVA by making payments through DVA for health services and programs to eligible veterans and their families and their carers. DVA issues various health cards (Orange, Gold and White card) that entitle holders to a range of health service benefits. The cards differ by the degree to which holders can access DVA health support and by eligibility criteria.

DVA-supported health services and treatments include mental health services, various medical and allied health services, rehabilitation support (including adaptive equipment, aids and appliances, and support to return to work), and benefit-paid pharmaceuticals (AIHW 2021b).

In 2019–20, DVA spent $2.9 billion on health-related services; the majority was spent on primary health care services ($1.4 billion) and hospital services ($1.3 billion) (AIHW 2021b).

Total DVA spending decreased by 1.8% in 2019–20. Over the decade to 2019–20, there was a consistent decline in DVA spending on hospital services, with spending on public hospital services decreasing by an average of 5.4% per year and private hospital services by 4.3% in real terms. DVA spending on primary health care also decreased in real terms by a yearly average of 2.8%, accompanied by an average decrease in spending on other services by 2.6%. This may be attributed to the declining size of the older DVA Gold Card population accessing fewer services, noting the average cost of providing support for Gold Card holders is higher than the other DVA Card types (AIHW 2018b; DVA 2021).

Based on the number of people in the DVA treatment population, DVA spent over $11,400 on health per member of the treatment population in 2019–20, which is 44% higher than the health spending per person in the total Australian population (around $7,900) (AIHW 2021b). This may reflect the different age profiles and subsequent needs of the DVA treatment population. Clients of DVA are also covered for services not covered for the general Australian population.

More information is available in the report Health expenditure Australia 2019–20.

Homelessness

Serving ADF members have access to housing and rental assistance through Defence Housing Australia. However, once members discharge from the ADF they are no longer able to access this housing support. Serving or ex-serving ADF members can access a range of housing and homelessness services through government and non-government organisations (Defence 2017).

To provide a better understanding of the extent to which serving and ex-serving ADF members may need support from specialist homelessness services (SHS), the self-reported Australian Defence Force (ADF) indicator3, termed ‘veteran SHS clients’ throughout the rest of this section, was introduced into the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC) in July 2017. In 2020–21, around 1,300 veteran SHS clients received support from specialist homelessness services (AIHW 2021c). This made up less than 1% of all SHS clients. All data presented below can be found in AIHW’s Specialist homelessness services annual report 2020–21.

Client characteristics

In 2020–21, of the veteran SHS clients:

- Two fifths of clients (41%) were not in the labour force (compared with 35% of all SHS clients).

- Around 2 in 5 lived alone (compared with 32% of all SHS clients).

- Two thirds (67%) had previously been assisted by SHS agency at some point since July 2011 (compared with 61% of all SHS clients).

Reasons for seeking assistance

- In 2020–21, the main reason for seeking assistance was experiencing housing crisis (21% or around 300 veteran SHS clients), followed by inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (14% or around 200 veteran SHS clients). By comparison, 53% of all SHS clients nominated accommodation issues and 34% of all SHS clients nominated experiencing housing crisis as the main reasons for seeking assistance.

- Both homeless and at-risk veteran SHS clients identified housing crisis as either their main reason or second main reason for seeking assistance (26% or around 200 veteran SHS clients and 17% or almost 100 veteran SHS clients respectively).

Housing situation

In 2020–21, of the veteran SHS clients:

- On presentation to services for assistance more than half (54%) were experiencing homelessness (compared with 43% of all SHS clients):

- 21% were rough sleeping (compared with 8.7% of all SHS clients).

- Around 1 in 5 (20%) were in short-term or emergency accommodation (compared with 16% of all SHS clients).

- Just under half (46%) presented to services at risk of homelessness (compared with 57% of all SHS clients):

- 26% were in private or other housing (compared with 31% of all SHS clients).

- 9.4% were in public or community housing (compared with 12% of all SHS clients).

1Patient days: The total number of days for all patients who were admitted for an episode of care and who separated during a specified reference period. A patient who is admitted and separated on the same day is allocated 1 patient day. METeOR identifier: 270045.

2 Funding sources includes public patients, private health insurance, self-funded, workers compensation, motor vehicle third party personal claims, DVA, and other.

3 The ADF indicator is not applicable to clients who may have served in non-Australian defence forces, reservists who have never served as a permanent ADF member or clients under the age of 18.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2019) Medications dispensed to contemporary ex-serving Australian Defence Force members, 2017–18, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.

AIHW (2020) Australia’s Health: Health of veterans, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.

AIHW (2021a) Hospitals – Admitted patient care 2019–20, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.

AIHW (2021b) Health expenditure Australia 2019–20, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.

AIHW (2021c) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.

Department of Defence (Defence) (2017) ADF member and family transition guide: a practical manual to transitioning, Department of Defence, Australian Government.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) (2018) ‘No cap on funds for medical treatment’, Vetaffairs Winter 2018, 34(2), Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Australian Government.

DVA (2021) Department of Veterans’ Affairs annual report 2020–21, DVA, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2022.