Hospitalisations

On this page

Page highlights

- There were 40,500 endometriosis-related hospitalisations in 2021–22. This represents 312 hospitalisations per 100,000 females.

- 82% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations were amongst females aged 15–44, representing 18 out of every 1,000 hospitalisations in this age group.

- The number of endometriosis-related hospitalisations increased by 43% between 2011–12 and 2021–22, from 28,400 to 40,500 hospitalisations, peaking at 43,800 in 2020–21.

- The rate of endometriosis hospitalisations has doubled among females aged 20–24 in the past decade, from 330 hospitalisations per 100,000 females in 2011–12 to 660 per 100,000 in 2021–22.

- There were just over 1,000 endometriosis-related hospitalisations for First Nations people, representing 2.5% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations.

- In 2021–22, 26% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations were among females born outside of Australia.

- Over two-thirds (68%) of endometriosis-related hospitalisations took place in a private hospital.

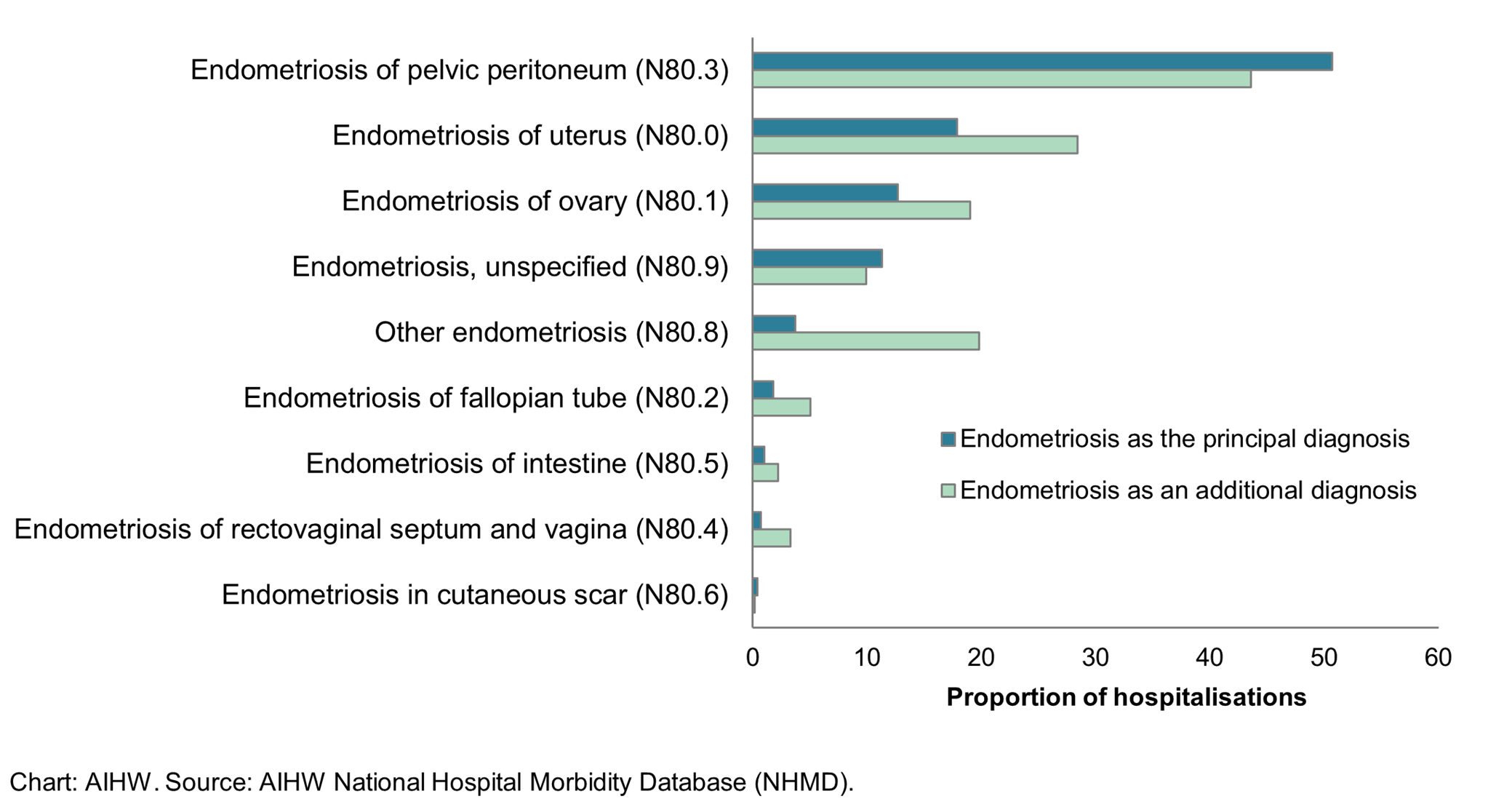

Around half (52%) of endometriosis-related hospitalisations in 2021–22 had endometriosis as the principal diagnosis according to the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). The remainder had endometriosis as an additional diagnosis only (48%). See Co-occurring diagnoses for information on other diagnoses commonly recorded for endometriosis-related hospitalisations.

About 1 in 3 (33%) hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of endometriosis also had one or more additional diagnoses of endometriosis.

Endometriosis of the pelvic peritoneum was the most common diagnosis among the hospitalisations, representing 51% of principal diagnoses and 44% of additional diagnoses (Figure 2). This was followed by endometriosis of the uterus (18% of principal and 28% of additional diagnoses), and of the ovary (13% of principal and 19% of additional diagnoses).

Figure 2: Endometriosis-related hospitalisations, by 4th character ICD-10-AM code, 2021–22

Notes

- Endometriosis of uterus (N80.0) includes adenomyosis. Other endometriosis (N80.8) includes endometriosis of thorax.

- The total proportion for endometriosis as an additional diagnosis exceeds 100% as some hospitalisations have more than one additional diagnosis of endometriosis.

What is an endometriosis-related hospitalisation?

- Hospitalisation data presented here are based on admitted patient episodes of care from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD), including multiple events experienced by the same individual in a given time frame.

- A separation is an episode of care for an admitted patient, which can be a total hospital stay (from admission to discharge, transfer or death) or a portion of a hospital stay beginning or ending in a change of type of care (for example, from acute care to rehabilitation). In this report, separations are referred to as hospitalisations.

- Hospitalisations with endometriosis as the principal diagnosis are hospitalisations for which endometriosis was determined to be chiefly responsible for occasioning the episode of admitted patient care.

- Hospitalisations with endometriosis as an additional diagnosis only are hospitalisations for which another condition was chiefly responsible for the episode of care, but endometriosis was determined to affect patient management.

- Some hospitalisations have endometriosis listed as both a principal and additional diagnosis. These hospitalisations are counted with the principal diagnosis group and excluded from the additional diagnosis group to avoid double counting.

- Endometriosis-related hospitalisations are hospitalisations with a principal and/ or additional diagnosis of endometriosis.

- A procedure is a clinical intervention that is surgical in nature, carries a procedural risk, carries an anaesthetic risk, requires specialised training and/or requires special facilities or equipment only available in an acute care setting.

- The health classification used for morbidity reporting in Australia is the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) which is used alongside the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI) which classifies procedures and interventions.

For further information on the NHMD and the methods used in this report, see the Technical notes.

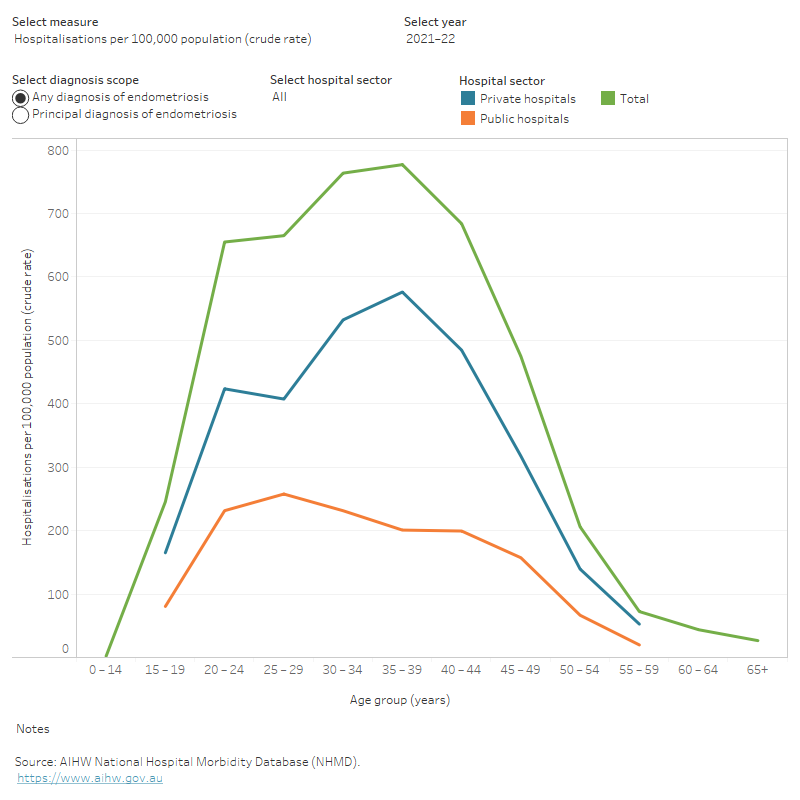

Variation by age

Most endometriosis-related hospitalisations (82% in 2021–22) are among females aged 15–44 (Figure 3), which are generally regarded as a woman’s reproductive years. This represents 18 out of every 1,000 hospitalisations among females in this age group. In comparison, 31% of all hospitalisations among females in 2021–22 were for this age group. Endometriosis was the 20th most common reason for hospitalisation among those aged 15–44 years (by principal diagnosis at the ICD-10-AM 3-character level). The most common reasons for hospitalisation among this age group are related to childbirth, procreative management, dialysis, and abdominal and pelvic pain.

There are few endometriosis-related hospitalisations among females aged under 15. The number and the rate of hospitalisations then rise with age to 30–39, before decreasing. There are relatively few hospitalisations among women aged 55 and over, potentially reflecting the decrease in endometriosis symptoms among most women after menopause.

Over the past decade, the rate of endometriosis-related hospitalisations increased across most age groups. The greatest increase was seen among ages 20–24, with the rate doubling between 2011–12 and 2021–22 (from 330 to 660 hospitalisations per 100,000 females). In 2021–22, 21 out of every 1,000 hospitalisations among females aged 20–24 were related to endometriosis. This trend was particularly driven by the increase in the rate of hospitalisations in private hospitals for women aged 20–24, which more than doubled from 175 to 425 hospitalisations per 100,000 females in this period.

Total bed days mirrors the pattern seen for hospitalisations, with the peak generally among ages 35–39.

Figure 3: Age profile of endometriosis-related hospitalisations, 2011–12 to 2021–22

Alt text: This interactive line chart shows the number, crude rate, and total bed days of endometriosis hospitalisations by age group, hospital sector and year. In 2021–22 the overall number of hospitalisations, rate of hospitalisation and total bed days were highest among females aged 35–39.

Trends over time

The number of endometriosis-related hospitalisations increased by 43% between 2011–12 and 2021–22, from 28,400 to 40,500 hospitalisations, peaking at 43,800 in 2020–21 (Figure 4). While hospitalisations in Australia are generally increasing over time, growth in the number of endometriosis-related hospitalisations was greater than that seen for all female hospitalisations between 2011–12 and 2021–22 (25%).

The rate of endometriosis-related hospitalisations also increased by 24% during this period, from 250 per 100,000 females in 2011–12 to 310 per 100,000 females in 2021–22. Over the same period, the rate of hospitalisation for all females increased by 9%.

Endometriosis-related hospitalisations increased by an average of 2.2% each year until 2019–20, when they decreased coinciding with the start of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and a temporary suspension of non-urgent elective surgery. Between 2019–20 and 2021–22, endometriosis-related hospitalisations fluctuated, influenced by the resumption of non-urgent elective surgery, as well as easing of restrictions that were implemented to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus more generally. See Impact of COVID-19 on endometriosis-related hospitalisations for further analysis of endometriosis-related hospitalisations during the pandemic period.

Overall, patterns of growth were seen across states and territories and by hospital sector, with slight differences year to year and following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021–22, hospitals located in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) had the highest rate of endometriosis-related hospitalisation (390 per 100,000 population), while hospitals in the Northern Territory had the lowest (170 per 100,000). These rates may be influenced by cross-border patient flows, where patients living in one jurisdiction attend a hospital in another jurisdiction. For example, 19% of total hospitalisations in the ACT in 2021–22 were for patients who lived in New South Wales (AIHW 2023).

Between 2011–12 and 2021–22, the hospitalisation rate in private hospitals increased by 37%, compared with a 4.0% increase in the rate in public hospitals. Most endometriosis-related hospitalisations occur in private hospitals; see Funding source for further analyses.

The median age of endometriosis patients has decreased slightly over the same period, from 37 in 2011–12 to 35 in 2021–22. Efforts to increase awareness of endometriosis among Australian women and medical practitioners may have contributed to this trend through earlier treatment and diagnosis (Armour et al. 2022).

Figure 4: Endometriosis-related hospitalisations, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This interactive line chart shows endometriosis-related hospitalisations by year and by hospital sector. The number and rate of hospitalisations for endometriosis were higher in private hospitals than public hospitals for all years. The median age was younger in public hospitals than private hospitals across all years. Similar patterns were seen for ages 15–44 as with all ages, and for a principal diagnosis of endometriosis as with any diagnosis of endometriosis.

Variation between population groups

In 2021–22, endometriosis-related hospitalisations varied between population groups (Figure 5). These differences could reflect potential variations in access to health services, including different barriers to access, or differences in health-seeking behaviour between population groups, rather than a difference in disease prevalence.

First Nations people

There were just over 1,000 endometriosis-related hospitalisations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) women in 2021–22, representing 330 hospitalisations per 100,000 females. About 2.5% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations were among First Nations women, compared with 5.9% of all female hospitalisations in this period.

The age-standardised rate for endometriosis-related hospitalisations among non-Indigenous Australians was 1.3 times the rate for First Nations women.

Socioeconomic area

The age-standardised rate for endometriosis-related hospitalisations for patients living in the highest socioeconomic areas was 1.4 times the rate for patients living in the lowest areas. This contrasts with the pattern seen among all female hospitalisations, where the age-standardised rate for patients living in the lowest socioeconomic areas was 1.3 times the rate for patients living in the highest areas.

Remoteness area

The age standardised-rate for endometriosis-related hospitalisations for patients living in Major cities was 1.8 times the rate for patients living in Remote and very remote areas. This contrasts with the pattern seen for all female hospitalisations, where the age-standardised rate for patients living in Remote and very remote areas was 1.8 times the rate for patients living in Major cities.

Figure 5: Endometriosis-related hospitalisations, by population group, 2021–22

Alt text: This interactive bar chart shows endometriosis-related hospitalisations by socio-economic group, remoteness area and Indigenous status. The crude rate of endometriosis hospitalisations was highest in the second most advantaged socioeconomic group and lowest in the most disadvantaged group. Crude hospitalisation rates were highest in Major cities and lowest in Remote and very remote areas. Similar patterns were seen for a principal diagnosis of endometriosis as with any diagnosis of endometriosis.

Country of birth

In 2021–22, 26% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations were among females born outside of Australia. This is similar to the proportion for all female hospitalisations (27%), and likely reflects the pattern seen in the general population, with 30% of females born outside of Australia (ABS 2021).

The rate of endometriosis-related hospitalisation varied by the region of birth (Figure 6). Rates were highest among patients born in the Americas, and lowest among patients born in Southern and Eastern Europe.

Median age also varied with country of birth. The median age of Australian-born endometriosis patients was lower than all other regions.

Figure 6: Endometriosis-related hospitalisations, by region of birth, 2021–22

Alt text: This interactive bar chart shows endometriosis-related hospitalisations by region of birth in 2021–22. Measures included are number of hospitalisations, hospitalisations per 100,000 population (crude rate) and median age. Australia had the highest number of hospitalisations at 29,980. The Americas had the highest crude rate of hospitalisations at 395 per 100,000 population. Australia had the youngest median age out of all regions at age 33.

Funding source

Most endometriosis-related hospitalisations were partly or fully funded by private health insurance (58%). A further 28% were for public patients, while 9.6% were for self-funded patients. Over two-thirds (68%) of endometriosis-related hospitalisations took place in a private hospital.

Compared with all female hospitalisations in 2021–22, endometriosis-related hospitalisations were more likely to be partly or fully funded by private health insurance, self-funded, or occur in a private hospital (Table 1a and Table 1b). As of June 2022, 16% of females aged 15–44 had private health insurance coverage for hospital treatment (APRA 2023).

| Funding source | Endometriosis hospitalisations, ages 15–44 (%) | Endometriosis hospitalisations, all ages (%) | All female hospitalisations, ages 15–44 (%) | All female hospitalisations, all ages (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Private health insurance (partly or fully funded) | 57.4 | 58.3 | 32.2 | 40.4 |

| Health service budget | 27.6 | 27.8 | 55.5 | 49.5 |

| Self-funded | 10.6 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 4.3 |

| Other | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 5.9 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

| Endometriosis hospitalisations, ages 15–44 (%) | Endometriosis hospitalisations, all ages (%) | All female hospitalisations, ages 15–44 (%) | All female hospitalisations, all ages (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public hospital | 31.5 | 31.6 | 62.5 | 57.7 |

| Private hospital | 68.5 | 68.4 | 37.5 | 42.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

Elective surgery waiting times for publicly-funded procedures may influence an individual’s decision to opt for privately-funded treatment. See Procedures for more information on common procedures for endometriosis and elective surgery waiting times.

Length of stay

Most endometriosis-related hospitalisations lasted 2 days or less, with 43% being same-day hospitalisations (Table 2). The average length of stay was slightly shorter for hospitalisations with endometriosis as a principal diagnosis, compared with that for all endometriosis-related hospitalisations.

The average length of stay for endometriosis-related hospitalisations was shorter than that for all female hospitalisations:

- 1.6 days compared with 2.7 days for all female hospitalisations

- 2.1 days compared with 5.4 days for all female hospitalisations excluding same-day hospitalisations.

| Hospitalisations with endometriosis as the principal diagnosis | All endometriosis-related hospitalisations | |

|---|---|---|

| Length of stay | % | % |

| Same day | 42.4 | 43.0 |

| 1–2 days | 47.7 | 44.5 |

| 3–4 days | 7.6 | 9.4 |

| 5–6 days | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| 7+ days | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Mean (days) | Mean (days) | |

| Length of stay | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Length of stay excluding same-day hospitalisations | 1.8 | 2.1 |

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

Procedures

In 2021–22, 94% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations involved at least 1 procedure (Table 3). Laparoscopic excision of lesion of pelvic cavity and diagnostic hysteroscopy were the most common procedures, each occurring in 42% of endometriosis-related hospitalisations.

| Rank | Procedure code | Procedure name | Description | Per cent of hospitalisations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35637-10 | Laparoscopic excision of lesion of pelvic cavity | Removal of lesions by cutting | 42.5 |

| 2 | 35630-00 | Diagnostic hysteroscopy | Examination of the inside of the uterus | 41.8 |

| 3 | 35640-00 | Dilation and curettage of uterus [D&C] | In which the lining of the uterus is scraped away | 37.9 |

| 4 | 30393-00 | Laparoscopic division of abdominal adhesions | In which adhesions are cut and divided | 23.6 |

| 5 | 35703-00 | Test for tubal patency | Assessment of whether fallopian tubes are blocked, used in investigating infertility | 18.6 |

| 6 | 35637-02 | Laparoscopic diathermy of lesion of pelvic cavity | Removal of lesions by burning | 17.0 |

| 7 | 35503-00 | Insertion of intrauterine device [IUD] | Insertion of a contraceptive device, which is also used in the treatment of endometriosis | 15.5 |

| 8 | 36812-00 | Cystoscopy | Examination of the inside of the bladder | 13.4 |

| 9 | 35638-10 | Laparoscopic salpingectomy, bilateral | Removal of both fallopian tubes | 12.0 |

| 10 | 35653-07 | Laparoscopic total abdominal hysterectomy | Removal of the uterus | 11.5 |

Notes:

- Procedures were counted only once if the same procedure was conducted more than once in a hospitalisation.

- Procedures for cerebral anaesthesia (ACHI block code 1910) and were not included in this analysis—these are companion procedures for many other procedures.

- ‘Diagnostic hysteroscopy’ is the name of a procedure in the ACHI and does not imply that this procedure is being used to diagnose endometriosis.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

Waiting times for procedures

Individuals seeking publicly-funded surgery for endometriosis will be added to the public hospital waiting list. It is not possible to identify waiting times specifically for the treatment of endometriosis, however some information is available on procedures which commonly occur in endometriosis-related hospitalisations.

Elective surgery waiting times

Elective surgery is planned surgery that can be booked in advance as a result of a specialist clinical assessment. Elective surgery is considered medically necessary, and may be required urgently, but is not conducted as a result of an emergency presentation. The National Elective Surgery Waiting Times Database captures data from procedures performed in public hospitals following a patient’s placement on a public hospital waiting list. The data on elective surgery waiting times is captured after the procedure is performed, so does not reflect the status of people currently waiting for surgery.

Some procedures for which waiting time information is available and may be used in the treatment of endometriosis include cystoscopy, hysteroscopy, dilation and curettage and laparoscopy (Table 4). It is important to note that these waiting times data include all sexes and are not limited to patients with a diagnosis of endometriosis.

According to the National Elective Surgery Waiting Times Database, in 2021–22

- Almost 52,000 cystoscopy (examination of the inside of the bladder) procedures were performed. Half of patients were admitted within 24 days, with 90% seen within 132 days.

- Just over 30,000 hysteroscopy, dilation and curettage procedures were performed. Half of patients had their procedure in less than a month (within 27 days), with 90% seen within 157 days.

- Almost 8,500 laparoscopy procedures were performed. Half of patients had their procedure in less than 3 months (within 78 days), with 90% seen within almost a year (354 days).

| Procedure | Number of procedures performed | Median waiting time (days) | Time waited at the 90th percentile (days) | Percentage of people who waited more than 365 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystoscopy | 51,749 | 24 | 132 | 1.6 |

| Hysteroscopy, dilation and curettage | 30,021 | 27 | 157 | 1.6 |

| Laparoscopy | 8,472 | 78 | 354 | 7.7 |

Note: Procedure names are based on the intended procedure code, see Elective surgery waiting list episode – intended procedure, code NNN.

Source: AIHW National Elective Surgery Waiting Times Database.

Co-occurring diagnoses

In 2021–22, 80% of hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of endometriosis had one or more additional diagnoses reported. Of these hospitalisations, 41% included another endometriosis diagnosis as an additional diagnosis.

Excluding endometriosis-related additional diagnoses, the most common additional diagnoses were female pelvic peritoneal adhesions (16% of hospitalisations) and peritoneal adhesions outside of the pelvis, such as on the abdominal wall or intestine (12%). Insertion of contraceptive device was recorded in 9.2% of hospitalisations.

For hospitalisations with endometriosis as an additional diagnosis, 21% had a principal diagnosis of pelvic and perineal pain. Diagnoses related to menstruation, infertility or in vitro fertilisation were also common.

A summary of the most common diagnoses co-occurring with endometriosis is included in the data tables.

Endometriosis and other chronic conditions

People with endometriosis may also experience other chronic conditions. The National Action Plan for Endometriosis supports the consideration of a number of related conditions, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease and chronic pelvic and period pain (Department of Health 2018). Some of these conditions are commonly co-occurring diagnoses with endometriosis (Tables 5 & 6).

Pelvic and perineal pain

Pelvic and perineal pain is a commonly reported symptom of endometriosis. In 2021–22, 29% of hospitalisations for pelvic and perineal pain had an additional diagnosis of endometriosis. In comparison, 2.5% of hospitalisations where endometriosis was the principal diagnosis had pelvic and perineal pain as an additional diagnosis.

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal condition, with common symptoms including irregular menstrual cycles, excess hair growth (hirsutism), acne, weight gain, infertility, as well as an increased risk of anxiety and depression (Better Health Channel, 2019). PCOS and endometriosis are conditions that affect the female reproductive system, and it is possible for both conditions to occur at the same time (Holoch et al. 2014). In 2021–22, 12% of hospitalisations for PCOS had an additional diagnosis of endometriosis. In the same year, less than 1.0% of hospitalisations for endometriosis had an additional diagnosis of PCOS.

Uterine fibroids

Uterine fibroids are noncancerous growths that can occur inside the uterus, as well as the fallopian tubes, cervix or tissues near the uterus (Health Direct 2021). Some common symptoms of uterine fibroids are heavy or prolonged periods, bleeding between periods, dysmenorrhoea (painful periods) and pain in the pelvic area. In some cases, uterine fibroids can also affect fertility (RANZCOG 2018). In 2021–22, 15% of hospitalisations for uterine fibroids had an additional diagnosis of endometriosis. In the same year, 4.6% of hospitalisations where endometriosis was the principal diagnosis also had a diagnosis of uterine fibroids.

Female pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) is an infection or inflammation of organs in the female reproductive tract, including the uterus, vagina and fallopian tubes (Better Health Channel 2022). In 2021–22, 3.0% of hospitalisations for PID had an additional diagnosis of endometriosis. Less than 1.0% of hospitalisations where endometriosis was the principal diagnosis had an additional diagnosis of PID.

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is a condition where cells similar to the lining of the uterus also grow in the muscle wall of the uterus (Jean Hailes for Women’s Health 2023). Like endometriosis, adenomyosis is characterised by the presence of endometrial-like tissue, and can cause similar symptoms related to pain, bleeding and infertility. In the ICD-10-AM, adenomyosis is grouped with endometriosis of the uterus, meaning it is not possible to know how many hospitalisations included a specific diagnosis of adenomyosis.

| Principal diagnosis | Proportion of hospitalisations with endometriosis as an additional diagnosis (%) | Total hospitalisations |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic and perineal pain | 29.3 | 13,913 |

| Uterine fibroids | 15.1 | 8,830 |

| Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) | 12.0 | 299 |

| Female pelvic inflammatory disease | 3.0 | 1,738 |

| Uterine/endometrial polyps | 2.5 | 10,418 |

| Chronic pain | 0.2 | 1,264 |

| IBS | 0.1 | 3,299 |

Note: For corresponding ICD-10-AM codes see Technical notes.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

| Additional diagnosis | Proportion of endometriosis hospitalisations with this additional diagnosis (%) |

|---|---|

| Uterine fibroids | 4.6 |

| Chronic pain | 3.1 |

| Pelvic and perineal pain | 2.5 |

| PCOS | 0.4 |

| Female pelvic inflammatory disease | 0.2 |

Notes:

- For corresponding ICD-10-AM codes see Technical notes.

- No hospitalisations with an endometriosis principal diagnosis had an additional diagnosis of IBS or Uterine/endometrial polyps.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2021), Australia's Population by Country of Birth, ABS Website, accessed 23 February 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2023) Admitted patients, AIHW website, accessed 20 November 2023.

APRA (Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) (2021), Quarterly private health insurance statistics, APRA Website, accessed 17 July 2023.

Armour M, Avery J, Leonardi M, Van Niekerk L, Druitt M, Parker M, Girling J, McKinnon B, Mikocka-Walus A, Ng C, O'Hara R, Ciccia D, Stanley K and Evans S (2022) 'Lessons from implementing the Australian National Action Plan for Endometriosis' Reproduction & Fertility, 3(3):29-39, doi:10.1530/RAF-22-0003.

Better Health Channel (2022) Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID), Better Health Channel website, accessed 2 February 2023.

Better Health Channel (2019) Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), Better Health Channel website, accessed 2 February 2023.

Department of Health (2018) National Action Plan for Endometriosis, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 15 July 2022.

Health Direct (2021) Uterine Fibroids, Health Direct website, accessed 2 February 2023.

Holoch KJ, Savaris RF, Forstein DA, Miller PB, Lee Hidgon H, Likes CE and Lessey BA (2014) 'Coexistence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Endometriosis in Women with Infertility' Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders, 6(2):79-83, doi:10.5301/je.5000181.

Jean Hailes for Women’s Health (2023) Adenomyosis, Jean Hailes for Women’s Health website, accessed 14 February 2023.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2018) Fibroids in infertility, RANZCOG, accessed 2 February 2023.