Hospitalisations

Page highlights:

- There were almost 1.3 million hospitalisations associated with diabetes in 2020–21 (11% of all hospitalisations in Australia).

- Most (72%) diabetes hospitalisations occurred in those aged 60 and over.

Type 1 diabetes hospitalisations

- There were around 64,600 hospitalisations where type 1 diabetes was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis.

- Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates as the principal diagnosis were highest among people aged 15–19.

Type 2 diabetes hospitalisations

- There were around 1.1 million hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21 with 96% as the additional diagnosis.

- Type 2 diabetes hospitalisations were 1.4 times as high among males as females, overall.

All diabetes hospitalisations

There were almost 1.3 million hospitalisations associated with diabetes in 2020–21. This represents 11% of all hospitalisations in Australia.

Of the almost 1.3 million hospitalisations associated with diabetes in 2020–21, 4.7% were recorded as the principal diagnosis (the diagnosis largely responsible for hospitalisation) and around 95% were recorded as an additional diagnosis (a coexisting condition with the principal diagnosis or a condition arising during hospitalisation that affects patient management), according to the AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).

In 2020–21, there were around:

- 59,400 hospitalisations with diabetes as the principal diagnosis. Over two-thirds were due to type 2 diabetes (69%) followed by type 1 diabetes (26%), gestational diabetes (4.2%) and diabetes ‘other or unspecified’ (1.8%).

- 1.2 million hospitalisations with diabetes as an additional diagnosis. Most were due to type 2 diabetes (89%) followed by gestational diabetes (5.5%), type 1 diabetes (4.2%) and diabetes ‘other or unspecified’ (1.1%).

What does a diabetes hospitalisation mean?

- Hospitalisation data presented here are based on admitted patient episodes of care from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD), including multiple admissions experienced by the same individual within a period of time.

- For a person living with diabetes, being admitted to hospital may be due to a range of things, including the initial diagnosis of diabetes, treatment for the management of diabetes or complications from diabetes, or an issue unrelated to diabetes itself.

- The health classification used for morbidity reporting in Australia is the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) which is used alongside the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI) which classifies procedures and interventions (refer to Data sources, methods and classifications).

- The Australian Coding Standards (ACS) are rules that direct the assignment of ICD-10-AM and ACHI codes to each record. Changes in the classification and coding standards over time impact the ability to monitor and report hospitalisation trends. Current coding standards require diabetes to be coded whenever documented in the medical record, even where diabetes may not be directly related to the hospitalisation. These standards mean that diabetes is more likely to appear in hospitals data compared to some other chronic conditions.

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, diabetes hospitalisation rates (principal and/or additional diagnosis):

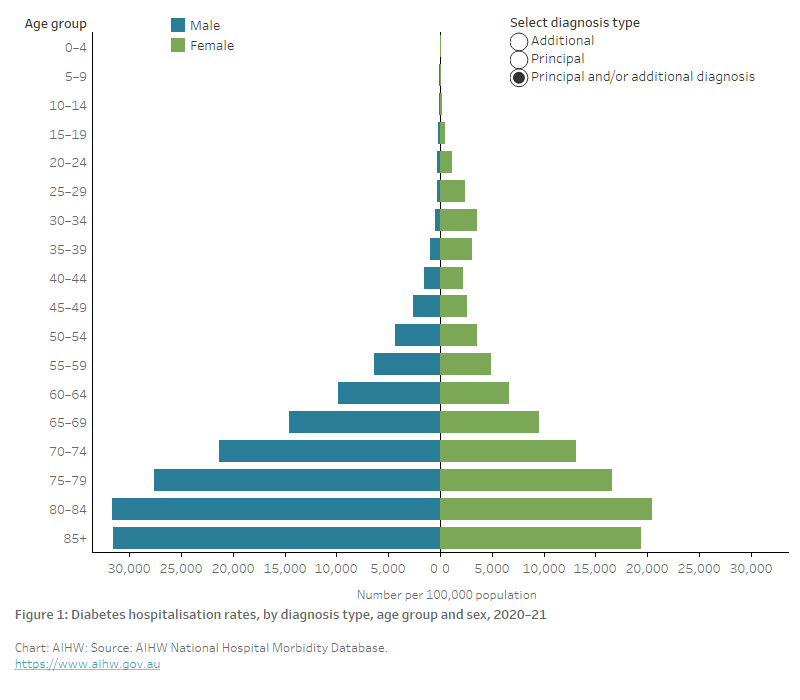

- were 1.2 times higher among males than females overall. Age-specific rates were higher among females than males in the younger groups (5 to 44 years) and higher among males from age 45 and over (Figure 1).

- generally increased with increasing age, with 72% of diabetes hospitalisations occurring in those aged 60 and over, peaking for both males and females in the 80–84 age group (31,700 and 20,500 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Diabetes hospitalisation rates, by diagnosis type, age and sex, 2020–21

The chart shows hospitalisation rates with diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis peaked in the 80–84 age group with 31,670 and 20,451 hospitalisations for males and females, respectively, per 100,000 population. With diabetes as the principal diagnosis, rates peaked among males aged 80–84 and females aged 85 and over (1,160 and 570 per 100,000 population, respectively). Rates with diabetes as an additional diagnosis peaked in the 80–84 age group with 30,510 and 19,881 per 100,000 population, respectively.

Trends over time

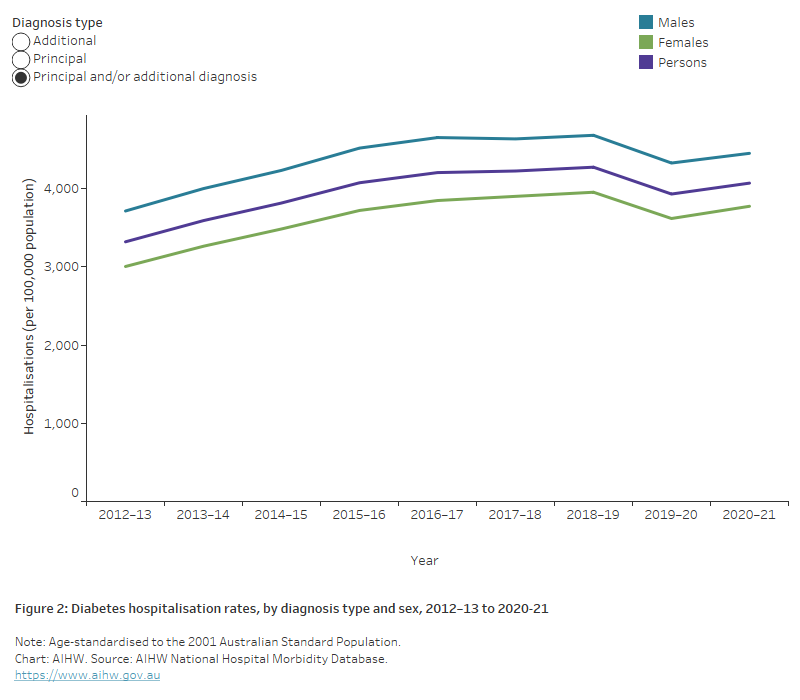

The number of hospitalisations with diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis increased by 49% between 2012–13 and 2020–21, from 837,000 to almost 1.3 million.

Between 2012–13 and 2018–19, there was a 29% increase in the age-standardised diabetes hospitalisation rate, followed by an 8.0% drop in 2019–20. The decline in 2019–20 may be associated with aspects of the early COVID-19 pandemic which had a profound impact on the provision of healthcare services and hospital activity generally (AIHW 2022). See Impact of COVID-19, Hospitalisations for more information. The diabetes hospitalisation rate increased slightly in 2020–21, yet remains 4.8% lower than the pre-pandemic peak of 2018–19.

The overall trend has displayed a similar pattern among both sexes, with diabetes hospitalisation rates consistently around 1.2 times higher among males compared with females (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Diabetes hospitalisations rates, by diagnosis type and sex, 2012–13 to 2020–21

The chart shows the increasing trend in the rate of hospitalisations with diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by sex from 2012-13 to 2019–20, for both males and females. Rates among males have consistently been around 1.2 times higher than among females. Hospitalisation rates peaked in 2018-19 at 4,268 per 100,000 population per year and declined slightly to 3,924 per 100,000 population in 2019-20. Hospitalisation rates with diabetes as a principal diagnosis have increased more gradually since 2012–13, and continued to record an increase in 2019–20 for males only.

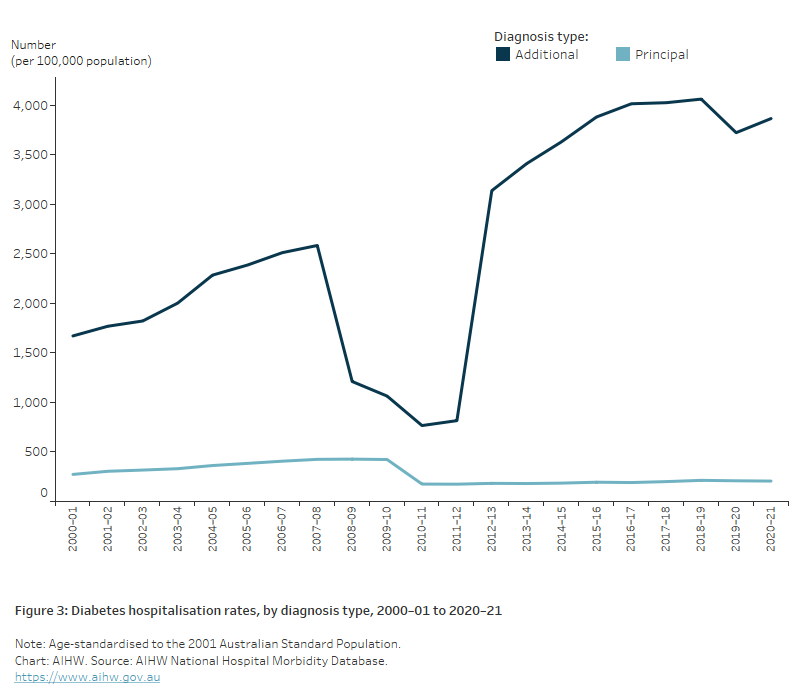

Impact of changes in coding over time

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) code changes in Chapter IV Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic disease and Australian Coding Standards (ACS) 0401 Diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia have affected the ability to monitor trends for diabetes hospitalisations. Transition between ICD-10-AM/Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI)/ACS classification editions has resulted in differences in how diabetes was recorded, when it had a direct relationship with the principal reason for the episode of care, or when it might be recorded as an additional diagnosis in any hospitalisation.

The coding practice for classifying diabetes under ICD-10-AM 6th edition (used 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2010) was largely consistent with previous editions of ICD-10-AM. However, clarification of how the coding standard for additional diagnoses should be applied (ACS 0002) meant that conditions would only be coded as an additional diagnosis if they were ‘significant in terms of treatment required, investigations needed, and resources used in each episode of care’. While this clarification resulted in a decrease in the number of conditions being coded as additional diagnoses for all hospitalisations, it had a particularly significant impact on the reporting of diabetes as an additional diagnosis.

The coding practice for classifying diabetes under ICD-10-AM 7th edition (used from 1 July 2010) changed again due to changes made to ACS 0401. The changes resulted in a further decrease between 2009–10 and 2010–11 in the reporting of diabetes-related conditions, due to the condition not meeting the criteria for being assigned as either the principal or additional diagnosis.

Following investigation into the effect of these changes to diabetes coding, an additional change to ACS 0401 that ‘when documented, diabetes mellitus should always be coded’ was implemented in July 2012.

The impact on reported diabetes hospitalisations:

- Between 2009–10 and 2010–11, the number of hospitalisations reported for diabetes decreased by 41% from around 442,000 in 2009–10 to 263,000 in 2010–11.

- Between 2010–11 and 2011–12, there were increases in the number of hospitalisations reported for diabetes that may be unrelated to coding changes.

- Between 2011–12 and 2012–13, the number of hospitalisations for which diabetes was recorded as either the principal and/or additional diagnoses increased – 8% increase where diabetes was recorded as the principal diagnosis, and a 250% increase where it was recorded as an additional diagnosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Diabetes hospitalisation rates, by diagnosis type, 2000–01 to 2020–21

The chart shows the rate of hospitalisations for diabetes, by diagnosis type from 2000–01 to 2019–20. Hospitalisation rates with a principal diagnosis of diabetes remained steady between 2000–01 to 2009–10 followed by a drop from 424 to 176 per 100,000 population in 2010–11 and have remained steady to 2019–20. Hospitalisation rates with an additional diagnosis of diabetes increased from 1,671 per 100,000 population in 2000–01 to 2,584 per 100,000 population in 2007–08 then declined to 766 per 100,000 population in 2010–11 before showing an increasing trend between 2011–12 and 2019–20 peaking at 4,055 per 100,000 population in 2018–19.

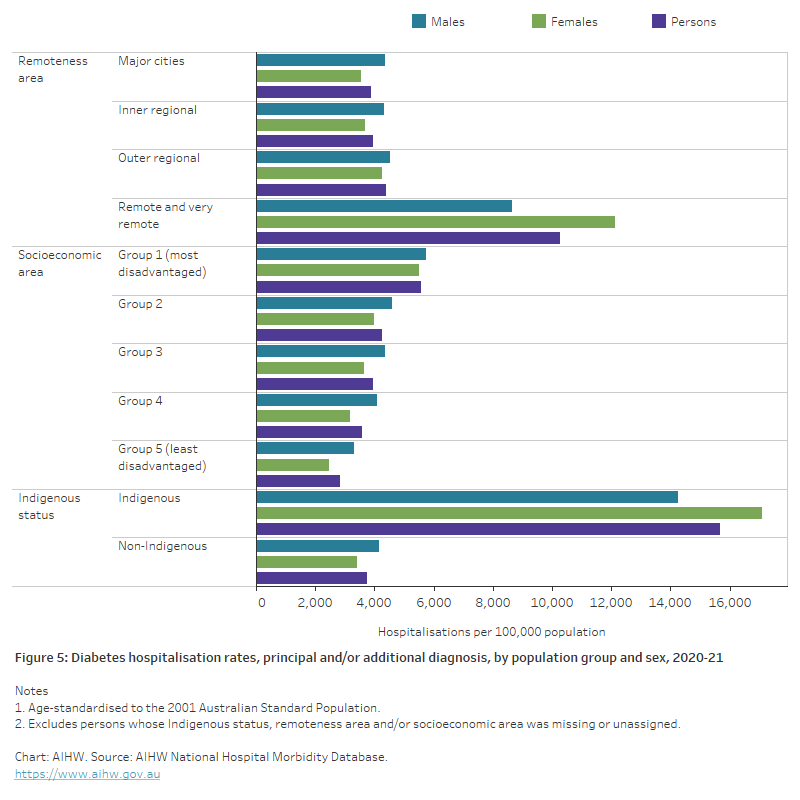

Variation between population groups

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

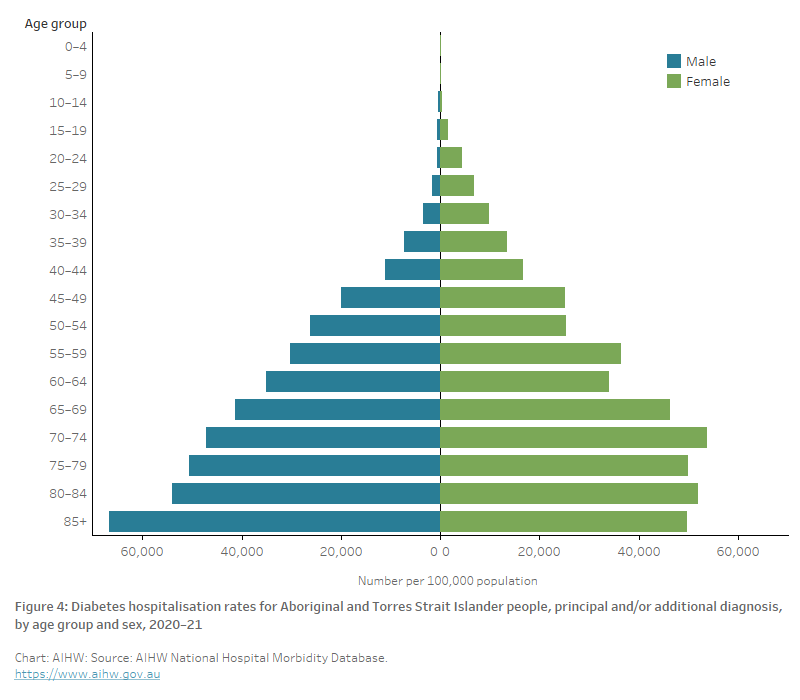

In 2020–21, there were around 85,500 hospitalisations associated with diabetes (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – a rate of 9,800 per 100,000 population. The rate generally increased with increasing age, peaking among Indigenous Australians aged 85 and over. Age-standardised rates were 1.2 times higher among Indigenous females as males, overall (Figure 4).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the rate of hospitalisation associated with diabetes among Indigenous Australians was 4.2 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Diabetes hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, by sex for 2020–21. Rates peaked for males in the 85+ year age group with 66,800 hospitalisations per 100,000 population and for females in the 70–74-year age group with 53,800 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the population, diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) were 1.7 times as high among those living in the lowest socioeconomic areas compared with those living in the highest socioeconomic areas (Figure 5).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the population, diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) were 2.6 times as high among those living in Remote and very remote areas as those living in Major cities (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Diabetes hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex for 2019–20. Rates increased with increasing remoteness and were highest among people living in Remote and very remote areas at 9,980 per 100,000 population compared to 3,720 per 100,000 population living in Major cities. Hospitalisation rates also increased gradually with increasing socioeconomic disadvantage. Those living in the most disadvantaged areas had the highest hospitalisation rates with 4,870 per 100,000 population compared with those living in the least disadvantaged areas with 2,777 per 100,000 population. Diabetes hospitalisation rates were 4.3 times higher among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared with non-Indigenous people.

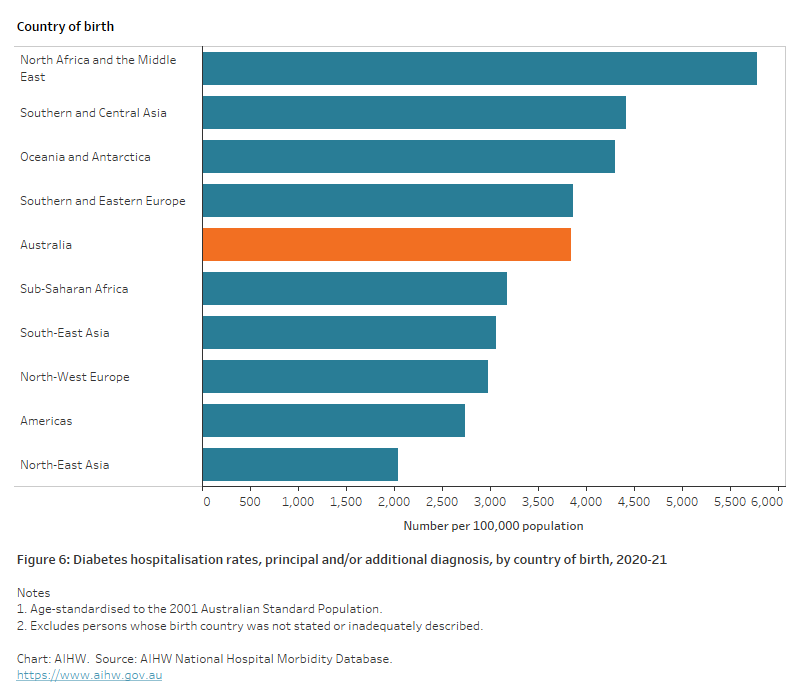

Country of birth

In 2020–21, diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) varied by country of birth. Almost two-thirds (64%) of diabetes hospitalisations were for people born in Australia – a rate of 3,800 per 100,000 population.

Of all diabetes hospitalisations among patients not born in Australia, the most common regions/countries of birth include North–West Europe (9.8%) and Southern and Eastern Europe (8.5%).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, diabetes hospitalisation rates were 1.5 times as high among those born in North Africa and the Middle East compared with those born in Australia (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Diabetes hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by country of birth, 2020–21

The chart shows the age-standardised hospitalisation rates with diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by country of birth for 2019–20. Diabetes hospitalisation rates were 1.5 times as high among those born in North Africa and The Middle East as those born in Australia.

Type 1 diabetes hospitalisations

There were around 64,600 hospitalisations where type 1 diabetes was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21, with 15,200 (24%) as a principal diagnosis and 49,500 (76%) as an additional diagnosis.

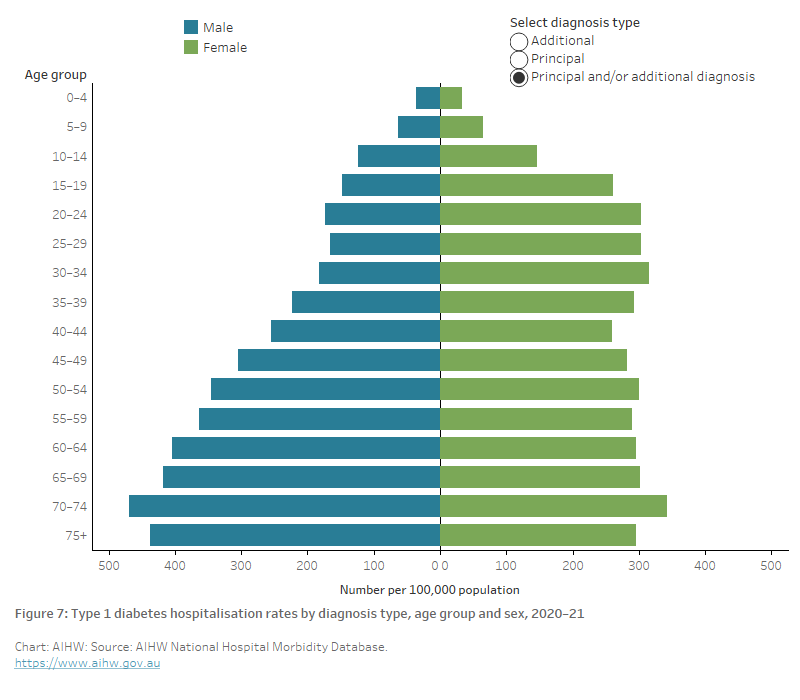

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis):

- increased with increasing age, with 62% of type 1 diabetes hospitalisations occurring in those aged 40 and over

- were highest among those aged 70–74 (470 and 342 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively) (Figure 7)

- were slightly higher among females than males overall, after controlling for differences in the age structures of the populations (Figure 8).

Where type 1 diabetes was the main reason for the hospitalisation (principal diagnosis), type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates were:

- highest among those aged 15–19 (83 and 114 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively) (Figure 7)

- similar among males and females after controlling for the age structures of the populations (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates by diagnosis type, age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with type 1 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis peaked in the 70–74-year age group with 470 and 342 hospitalisations for males and females, respectively, per 100,000 population.

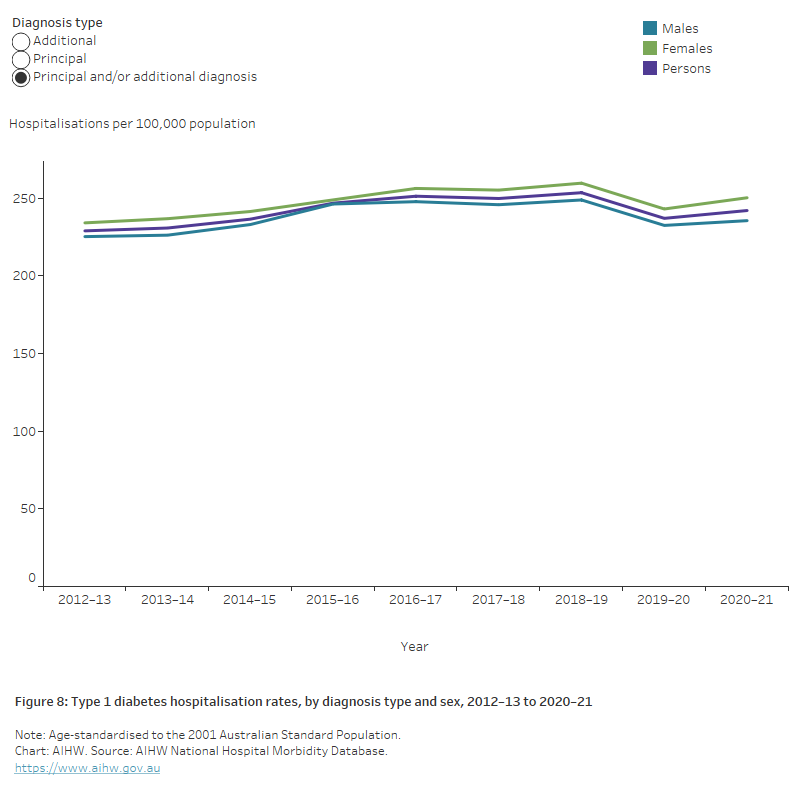

Trends over time

Between 2012–13 and 2020–21, there was a 20% increase in the number of hospitalisations for patients with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (from 53,900 to 64,600 hospitalisations).

After adjusting for age, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates (principal and/or additional diagnosis) increased steadily by around 6% between 2012–13 and 2020–21 (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates, by diagnosis type and sex, 2012–13 to 2020–21

The chart shows hospitalisations rates for type 1 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis increased by 5.7% between 2012–13 and 2020–21 with the rates consistently slightly higher among females than males over this period.

Variation among population groups

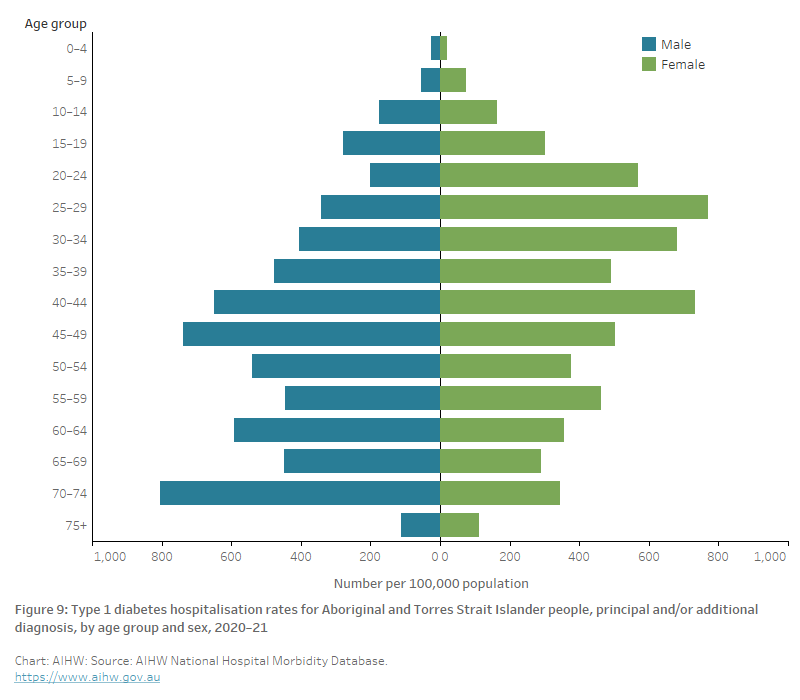

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 3,000 hospitalisations for type 1 diabetes (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (341 per 100,000 population), with 55% of these hospitalisations being among Indigenous females.

Among Indigenous Australians, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) were highest among males aged 70–74 and females aged 25–29 (803 and 771 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 9).

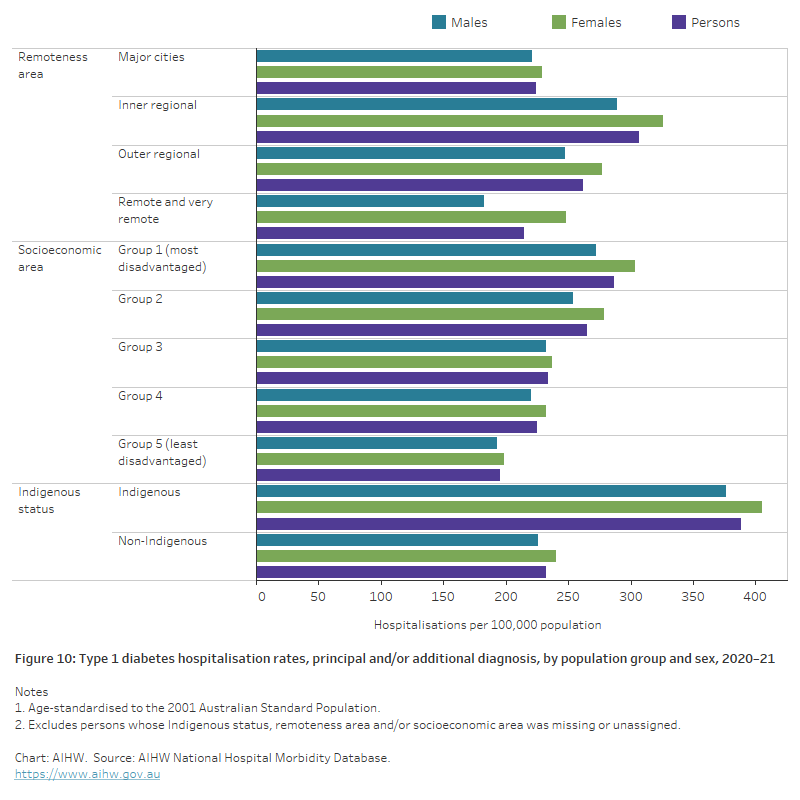

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rate among Indigenous Australians was 1.7 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 10).

Figure 9: Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The chart shows hospitalisations with type 1 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, by sex for 2020–21. Rates peaked for males in the 70–74 age group with 803 hospitalisations per 100,000 population and for females in the 25–29 age group with 771 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) increased with increasing levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. Age-standardised rates were 1.5 times as high among those living in the lowest socioeconomic areas as those living in the highest socioeconomic areas (Figure 10). This difference was similar for males and females.

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) varied by remoteness area. Age-standardised rates were between 1.2 and 1.4 times higher in Inner regional and Outer regional areas compared with Major cities and Remote and very remote areas (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The chart shows hospitalisations with type 1 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex for 2020–21. Rates among remoteness areas were highest in Inner regional areas with 307 per 100,000 population compared to 214 per 100,000 population in Remote and very remote areas. Age-standardised rates were 1.5 times as high among those living in the lowest socioeconomic areas as those living in the highest socioeconomic areas and 1.7 times higher among Indigenous as non-Indigenous Australians.

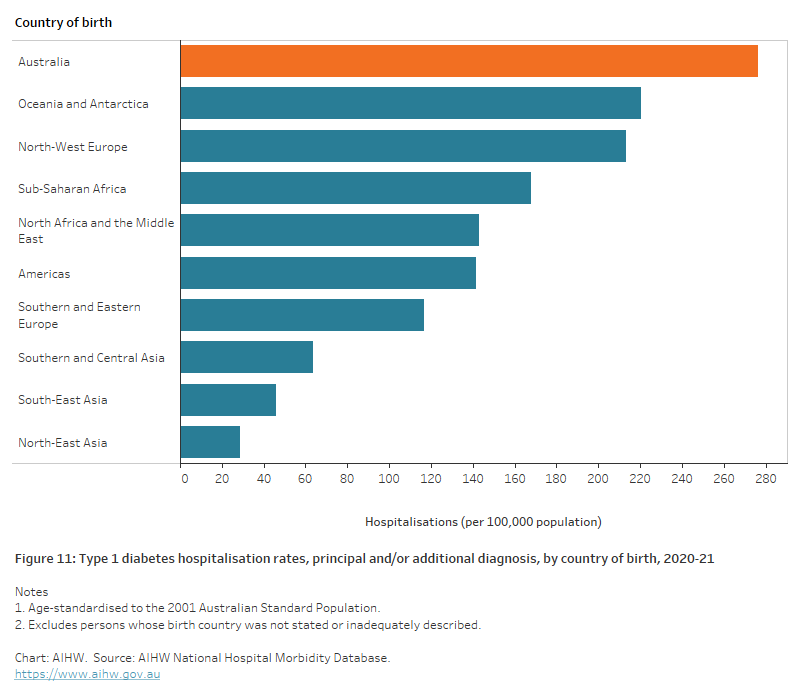

Country of birth

A person’s country of birth commonly affects the risk of developing type 1 diabetes – this can often be attributed to the interaction of genetic, environmental and cultural factors (Hjern and Söderström 2008).

In 2020–21, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) varied by country of birth. Most (81%) patients admitted to hospital for type 1 diabetes were born in Australia. Of those patients not born in Australia, the most common regions/countries of birth include North–West Europe (7.6%) and Oceania and Antarctica (3.2%).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates were highest for people born in Australia and lowest for those born in North–East Asia (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by country of birth, 2020–21

The chart shows the age-standardised hospitalisations for type 1 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by country of birth for 2020–21. Type 1 diabetes hospitalisation rates were highest among people born in Australia (276 per 100,000 population) and lowest among those born in North-East Asia (29 per 100,000 population).

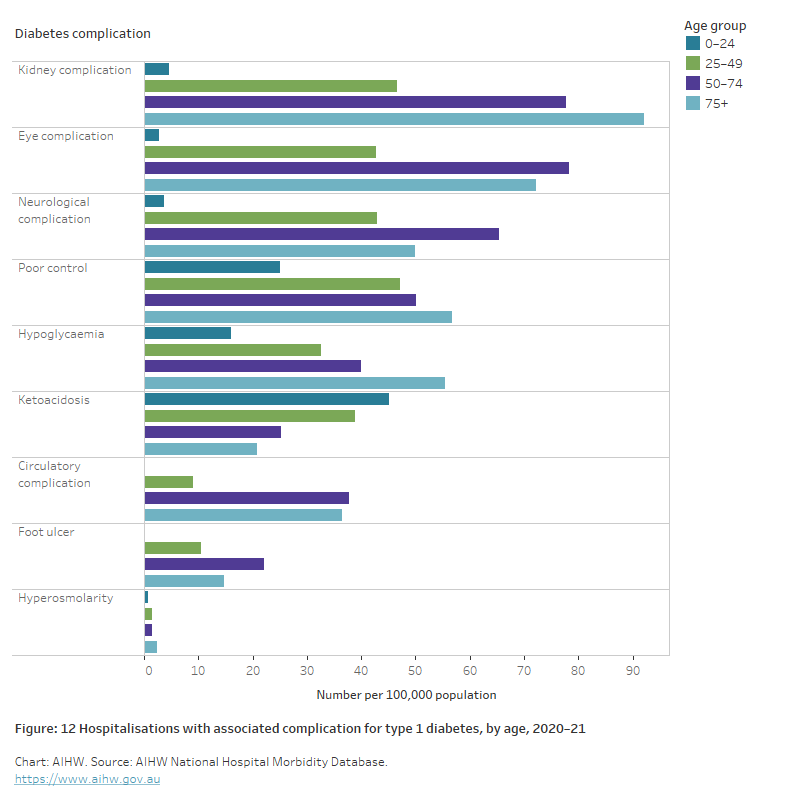

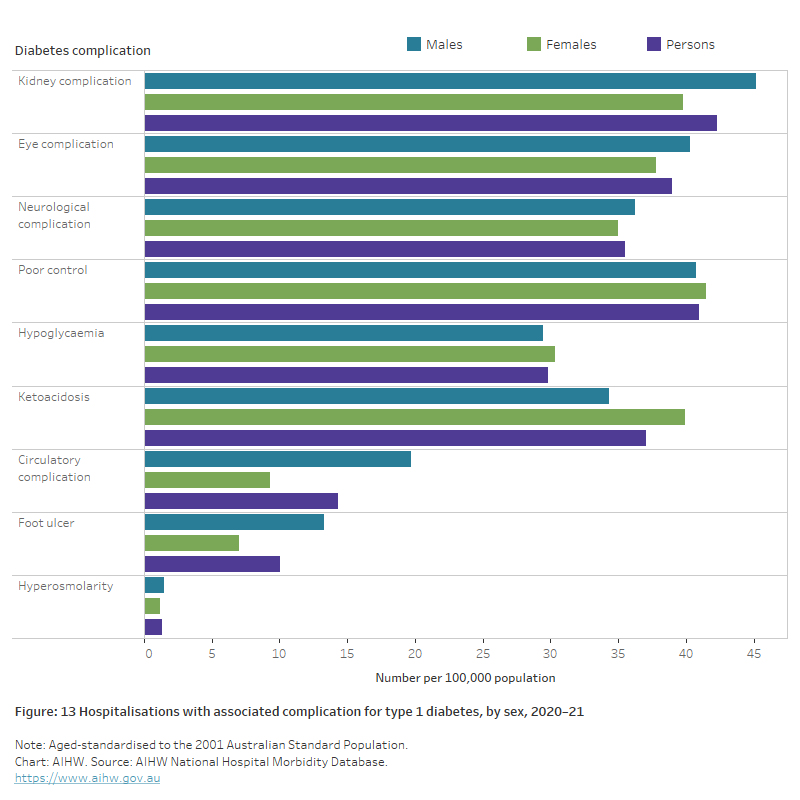

Type 1 diabetes hospitalisations with diabetes complications

In 2020–21, there were around 36,300 hospitalisations with one or more acute or chronic diabetes complications associated with the hospitalisation for people with type 1 diabetes (56% of all type 1 diabetes hospitalisations). Suboptimal diabetic control, kidney, eye and neurological complications, and ketoacidosis were the most common hospital complications found for people with type 1 diabetes.

Issues with diabetes complications

Diabetes complications which are detected in the hospital setting are considered material to the hospitalisation and do not represent all complications a patient may have or the number of people with diabetes affected by these complications (prevalence). People who are hospitalised with diabetes are more likely to represent complex cases and are more likely to suffer from one or more diabetes complications than people who are not hospitalised.

Further research is required to fully understand the prevalence of these complications in the broader diabetes community at the national level. The accuracy of diagnosis of some complications may also be an issue. In recent research by Davis and Davis (2019) assessing the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis in the Fremantle Diabetes Study, incorrect coding rates of 39% were found for initial episodes and 41.7% for recurrent episodes.

In 2020–21, there were:

- 11,700 hospitalisations with kidney complications (45 per 100,000 population).

- 10,800 hospitalisations with eye complications (42 per 100,000 population).

- 10,700 hospitalisations with suboptimal diabetic control (42 per 100,000 population).

- 9,600 hospitalisations with neurological complications (38 per 100,000 population).

- 9,200 hospitalisations with ketoacidosis (36 per 100,000 population).

Age and sex

In 2020–21:

- Hospitalisations with associated diabetes complication were generally higher in Australians aged 50 and over (Figure 12).

- Females aged 0–24 were 1.4 times as likely to be hospitalised with ketoacidosis compared with males aged 0–24.

Figure 12: Hospitalisations with associated diabetes complications for type 1 diabetes, by age, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with associated diabetes complications for type 1 diabetes, by age group for 2020–21. The most common complication associated with hospitalisations for type 1 diabetes were kidney and eye complications. The rate of kidney complications peaked among those aged 75+ at 92 per 100,00 population and eye complications peaked among people aged 50–74 with 78 per 100,000 population. The only complication where rates reduced with increasing age was ketoacidosis which peaked among people aged 0–24 at 45 per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for different population age structures:

- Males were more likely to have hospitalisations associated with chronic diabetes complications including foot ulcer, kidney, eye, neurological and circulatory complications.

- Circulatory complications and foot ulcer were 2.2 and 1.9 times as high, respectively, in males compared with females.

- Females were slightly more likely to have hospitalisations associated with acute complications including ketoacidosis (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Hospitalisations with associated diabetes complications for type 1 diabetes, by sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with associated diabetes complications for type 1 diabetes, by sex for 2020–21. Males were more likely than females to have hospitalisations associated with type 1 diabetes complications including foot ulcer, kidney, eye, neurological and circulatory complications. Ketoacidosis was the only complication where rates were notably higher among females than males (1.2 times higher).

Type 2 diabetes hospitalisations

There were around 1.1 million hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis in 2020–21, with 40,700 (3.7% of type 2 diabetes hospitalisations) as the principal diagnosis and 1,060,000 (96% of type 2 diabetes hospitalisations) as an additional diagnosis.

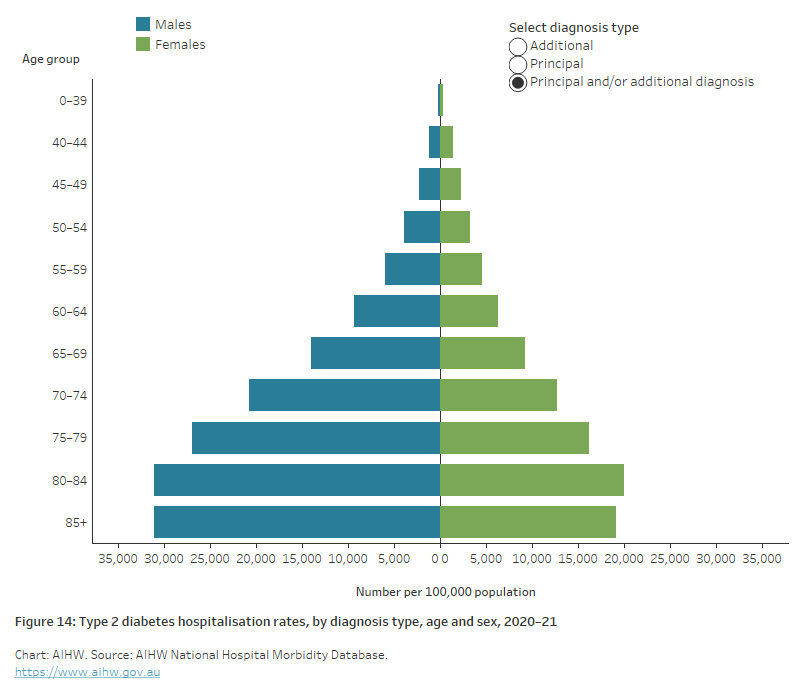

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, type 2 diabetes hospitalisations (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis):

- generally increased with increasing age, with most (87%) occurring in those aged 55 and over. Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates were highest among those aged 80–84 (31,000 and 20,000 per 100,000 population for males and females, respectively).

- were higher among males than females from age 50 onwards (Figure 14).

- were 1.4 times as high for males as females, after controlling for the age structure of the population (Figure 15).

Where type 2 diabetes was the main reason for the hospitalisation (principal diagnosis), the age-standardised hospitalisation rate was 2.0 times as high among males compared with females (Figure 15).

Figure 14: Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates by diagnosis type, age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis peaked in the 80–84 age group with 31,069 and 20,030 hospitalisations for males and females, respectively, per 100,000 population. Hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes as a principal diagnosis were around twice as high among males as females peaking the 80–84 age group with 1,106 and 534 hospitalisations per 100,000 for males and females, respectively.

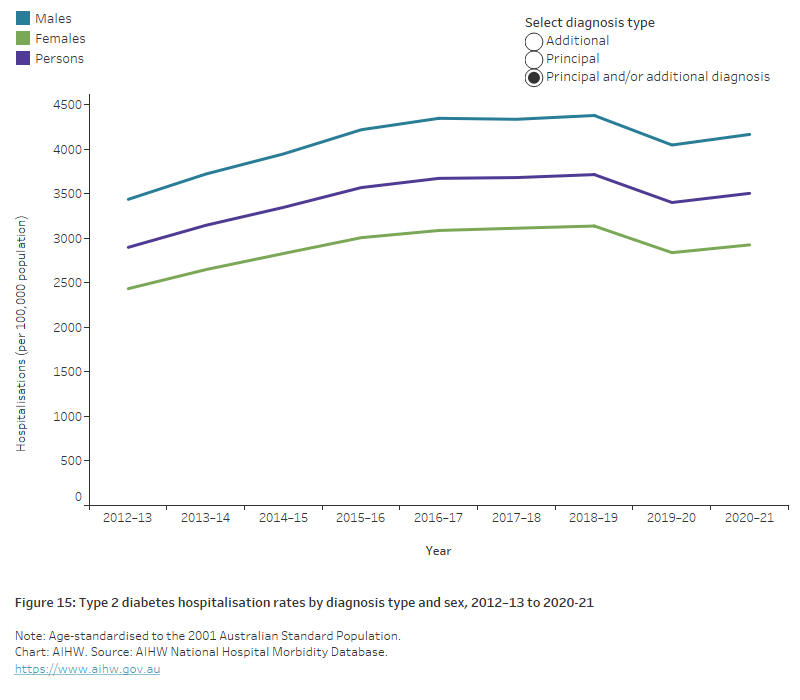

Trends over time

After adjusting for age, type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates (principal and/or additional diagnosis) increased steadily by around 21% overall between 2012–13 and 2020–21. With a peak in 2018–19, the trend was similar among both sexes, with rates among males consistently around 1.4 times as high compared with females (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates by diagnosis type and sex, 2012–13 to 2020–21

The chart shows the rate of hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis increased 21% overall between 2012-13 to 2020–21, for both males and females. A slight dip in rates in 2019–20 was followed by an increase again in 2020–21. Throughout this period, rates have remained around 1.4 times higher among males than females.

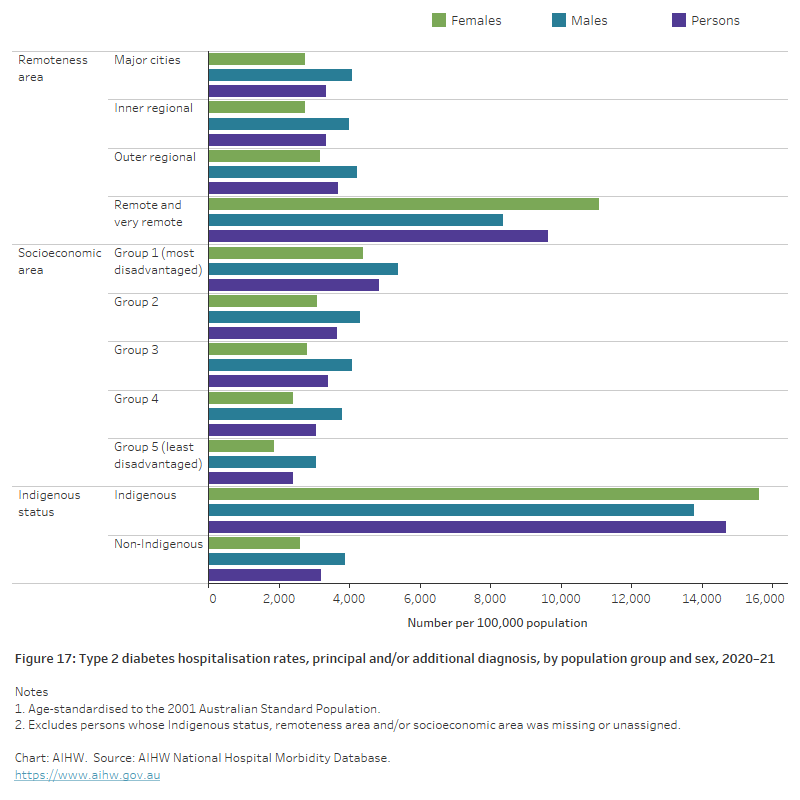

Variation between population groups

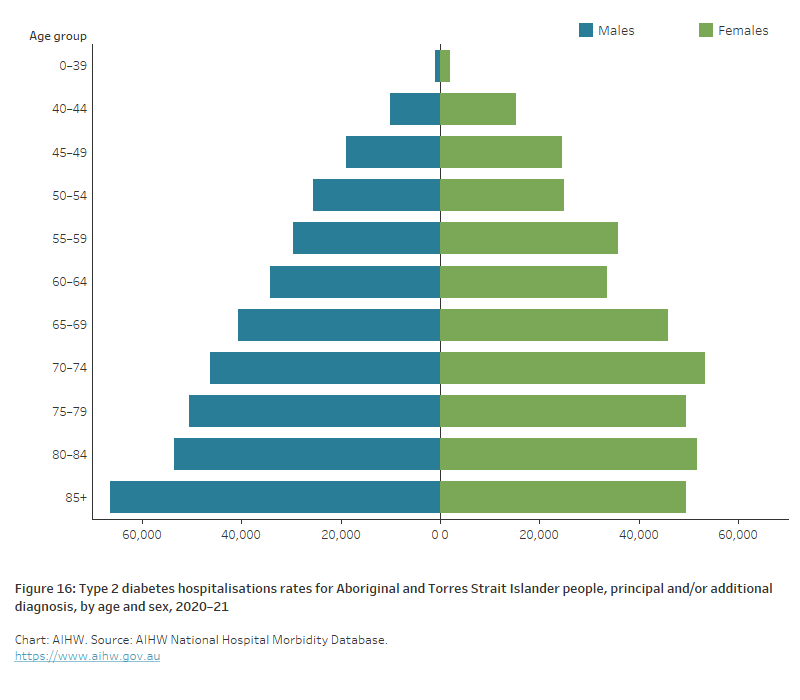

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2020–21, there were around 77,500 hospitalisations for type 2 diabetes (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – a rate of 8,900 per 100,000 population. The hospitalisation rates were highest among Indigenous females aged 70–74 and Indigenous males aged 85 or higher (53,300 and 66,400 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 16). Indigenous women were 1.1 times as likely to be hospitalised with type 2 diabetes when compared with Indigenous males after controlling for age.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the populations, the hospitalisation rate for type 2 diabetes among Indigenous Australians was 4.6 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 17).

Figure 16: Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by age and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, by sex for 2020–21. Rates peaked for males in the 85+ year age group with 66,402 hospitalisations per 100,000 population and for females in the 70–74-year age group with 53,316 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

Socioeconomic area

In 2020–21, age-standardised type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) increased with increasing levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. People living in the lowest socioeconomic areas were 2.0 times as likely to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes as those living in the highest socioeconomic areas (Figure 17).

Remoteness area

In 2020–21, age-standardised type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates (as the principal and/or additional diagnosis) were 2.6 to 2.9 times as high in Remote and very remote areas, compared with Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas (Figure 17).

See Geographical variation in disease: diabetes, cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease for more information on type 2 diabetes hospitalisations by state/territory, Population Health Network and Population Health Area.

Figure 17: Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows the age-standardised hospitalisation rate with type 2 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by population group and sex for 2020–21. Rates increased with increasing remoteness and were 2.9 times higher among those living in Remote and very remote areas compared with those living in Major cities. Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates increased with increased socioeconomic disadvantage being 2.0 times higher among those living in the most disadvantaged areas compared with those living in the least disadvantaged areas. Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates among Indigenous Australians were 4.6 times higher than for non-Indigenous Australians.

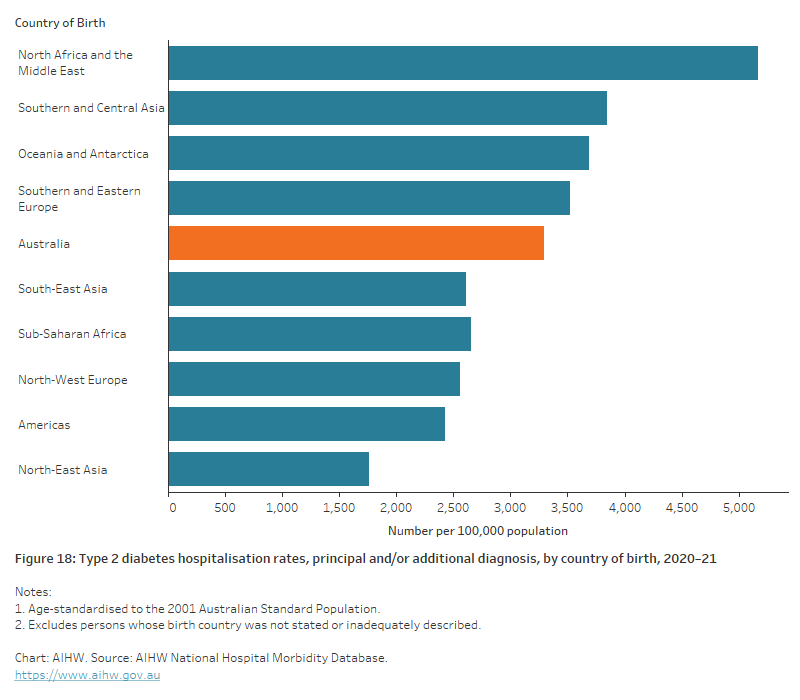

Country of birth

A person’s country of birth commonly affects their risk of developing type 2 diabetes, however, the degree to which this is influenced by migration or ethnicity is unclear. Potential reasons may include genetic predisposition, potential exposure to risk factors in the country of origin, factors related to the migration process and/or changes in lifestyle behaviours following migration (Zhang et al. 2020).

In 2020–21, 64% of hospitalisations with type 2 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis were for people born in Australia (653,000 hospitalisations). Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates varied by country of birth, with age-standardised rates for people born in Northern Africa and the Middle East being 1.6 times as high compared with those born in Australia. Hospitalisation rates were lowest among those born in North–East Asia (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates, principal and/or additional diagnosis, by country of birth, 2020–21

The chart shows the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for type 2 diabetes as the principal and/or additional diagnosis, by country of birth for 2020–21. Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates for people born in Northern Africa and the Middle East were 1.6 times as high compared with those born in Australia.

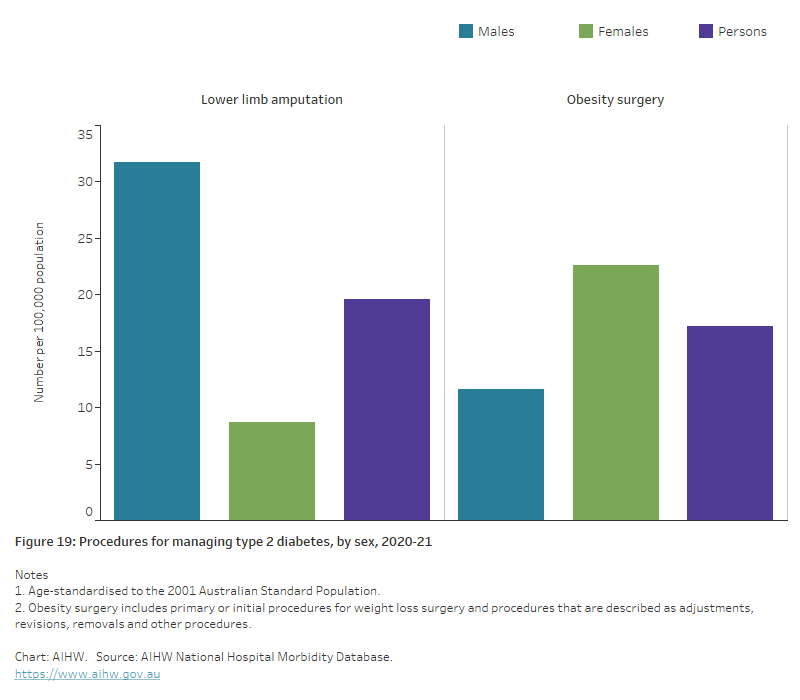

Type 2 diabetes hospital procedures

According to the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD), there were around 4,500 weight loss procedures and 6,100 lower limb amputations undertaken for people with type 2 diabetes in 2020–21 (18 and 24 per 100,000 population, respectively).

People with diabetes may require surgery to help manage their diabetes or treat the complications of diabetes.

Weight loss reduces the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and reduces long-term complications associated with type 2 diabetes and obesity. Lifestyle interventions are the primary method for reducing weight, but in some people weight loss (bariatric) surgery is an effective intervention for long-term weight loss and maintenance (Lee and Dixon 2017).

Diabetes can cause damage to the nerves in the feet which reduces blood circulation and increases risk of infection and foot ulcers. Diabetic foot ulcers can lead to hospitalisation and require lower limb amputation (Reardon et al. 2020).

Variation by age and sex

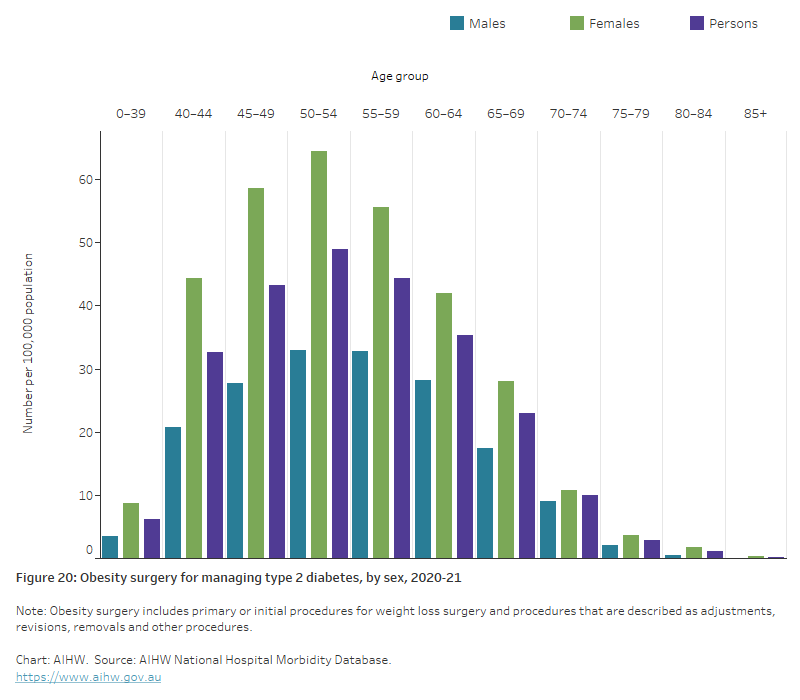

In 2020–21, rates for obesity surgery among people living with type 2 diabetes were:

- 1.9 times as high in females compared with males after controlling for age (Figure 19)

- highest in people aged 50–54 (49 per 100,000), over 8 times as high as those aged 0–39 and 245 times as high as people 85 and over (Figure 20).

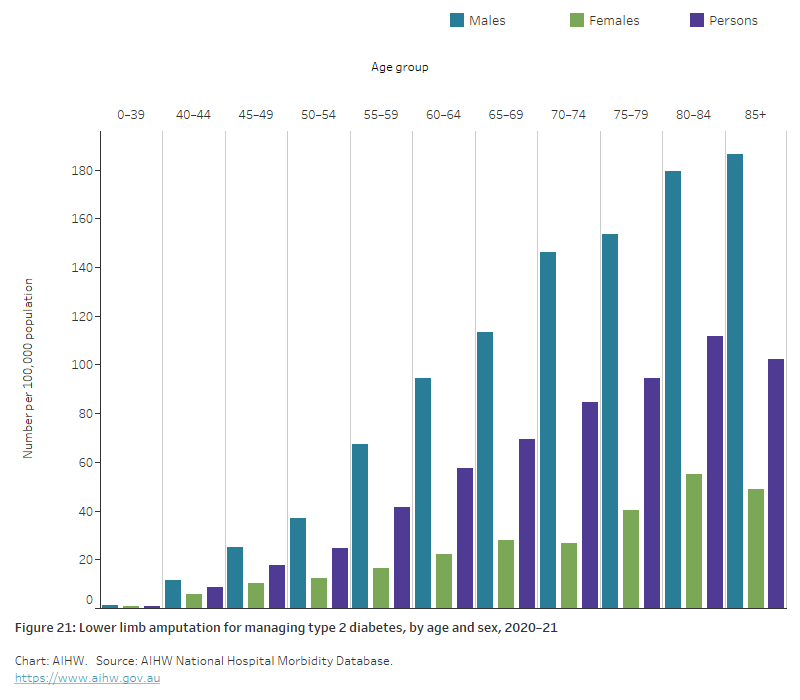

Rates of lower limb amputation among people living with type 2 diabetes:

- were 3.6 times as high in males compared with females after controlling for age (Figure 19)

- generally increased with increasing age, with 74% of lower limb amputations undertaken in people aged 60 or abover (Figure 21)

- were highest among people aged 80–84 (112 per 100,000 population), which was 124 times as high as for those aged 0–39 (0.9 per 100,000 population) (Figure 21).

Counting hospital procedures

The number and rate of procedures reported in this section should be interpreted with caution. Hospital procedures reported using the NHMD may represent many individuals undergoing these procedures, or in some cases, a single individual undergoing multiple procedures over time as they require further follow-up and treatment. In 2011, it was estimated that only 1.7% (12,300) of people living with diabetes had experienced one or more lower limb amputation procedures despite 4,200 lower limb procedures being undertaken in that year and similar numbers in the years prior (AIHW 2017). This implies that there are high number of people who have multiple amputations to treat the complications from diabetes. Further research is required to understand the differences between the number of separations for these procedures and the number of individuals who have undergone the procedures.

Figure 19: Procedures for managing type 2 diabetes, by sex, 2020–21

The bar chart shows age-standardised rates of procedures for managing type 2 diabetes, by sex for 2020–21. Rates for lower limb amputation were higher for males than females with 32 and 9 hospitalisations respectively, per 100,000 population. Hospitalisations for obesity surgery were higher among females than males with 23 and 12 hospitalisations per 100,000, respectively.

Figure 20: Obesity surgery for managing type 2 diabetes, by age and sex, 2020–21

The chart shows rates of obesity surgery for managing type 2 diabetes, by sex and age for 2020–21. Rates peaked for both males and females in the 50–54-year age group with 33 and 64 procedures for males and females, respectively, per 100,000 population.

Figure 21: Lower limb amputation for managing type 2 diabetes, by age and sex, 2020–21

The chart shows rates of lower limb amputations for managing type 2 diabetes, by sex and age for 2020–21. Rates peaked among males in the 85 and over age group and females in the 80–84 age group with 187 and 55 procedures for males and females, respectively, per 100,000 population.

Type 2 diabetes hospitalisations with diabetes complications

In 2020–21, there were over 560,000 hospitalisations with acute or chronic diabetes complications associated with the hospitalisation for people living with type 2 diabetes (51% of all type 2 diabetes hospitalisations). This was down from 608,000 in 2019–20 (52% of all type 2 diabetes hospitalisations). Kidney, eye, neurological, circulatory and poor diabetes control were the most common hospital complications found for people living with type 2 diabetes.

In 2020–21, there were:

- 244,900 hospitalisations with kidney complications (955 per 100,000 population).

- 103,200 hospitalisations with eye complications (402 per 100,000 population).

- 84,000 hospitalisations with neurological complications (328 per 100,000 population).

- 69,200 hospitalisations with circulatory complications (270 per 100,000 population).

- 61,100 hospitalisations with poor diabetes control (238 per 100,000 population).

Variation by age and sex

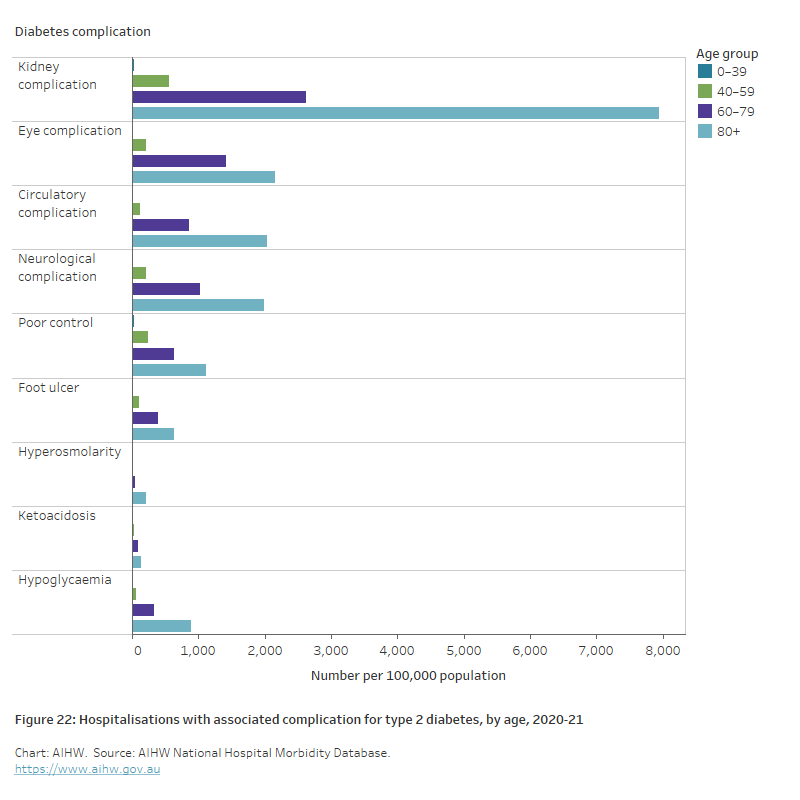

In 2020–21:

- kidney complications were the most reported complication in both males and females with type 2 diabetes

- the rate of hospitalisation with associated complication for type 2 diabetes increased with increasing age and was highest among people aged 80 and over for all complications (Figure 22)

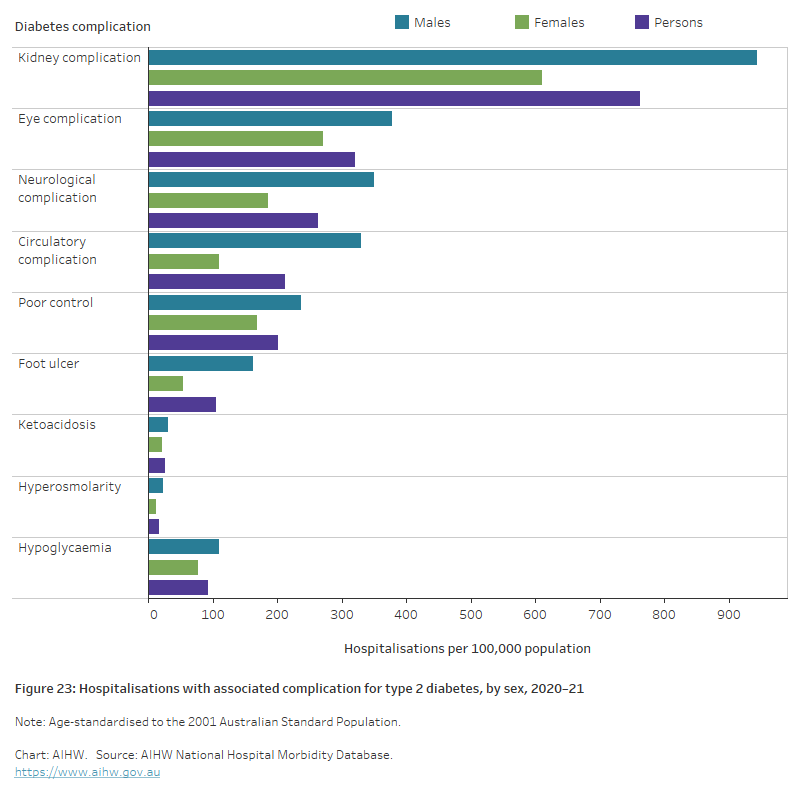

- type 2 diabetes complications were reported 1.3 times more frequently among males than females, after controlling for age (Figure 23).

The chart shows hospitalisations for type 2 diabetes with associated diabetes complications, by age for 2020–21. Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates were highest in the 80+ age group across all complications with kidney complications having the highest rate at 7,941 hospitalisations per 100,000 population.

After adjusting for different population age structures:

- males had higher rates for all complications compared with females

- rates were 3.1 times as high for males compared with females for foot ulcer, 3.0 times as high for circulatory complications, 1.9 times as high for neurological complications, and 1.5 times as high for kidney complications and ketoacidosis (Figure 23).

Figure 23: Hospitalisations with associated diabetes complications for type 2 diabetes, by sex, 2020–21

The chart shows age-standardised hospitalisation rates for type 2 diabetes with associated diabetes complications, by sex for 2020–21. Type 2 diabetes hospitalisation rates were highest for males across all complications with Kidney complications having the highest rate for both males and females with 943 and 611 hospitalisations for males and females, respectively, per 100,000 population.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2017) Burden of lower limb amputations due to diabetes in Australia: Australian Burden of Disease Study 2011, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 4 March 2022.

AIHW (2022) Australia's hospitals at a glance, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2022.

Davis TM and Davis W (2020), 'Incidence and associates of diabetic ketoacidosis in a community-based cohort: the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II', BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care, 8(1):e000983, doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000983.

Hjern A and Söderström U (2008), 'Parental country of birth is a major determinant of childhood type 1 diabetes in Sweden', Pediatric diabetes, 9(1):35-9, doi:10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00267.x.

Lee PC and Dixon J (2017), 'Bariatric-metabolic surgery: A guide for the primary care physician', Australian family physician, 46(7): 465-471, PMID:28697289.

Reardon R, Simring D, Kim B, Mortensen J, Williams D and Leslie A (2020), 'The diabetic foot ulcer', Australian Journal of General Practice, 49(5): 250-255, doi:10.31128/AJGP-11-19-5161.

Zhang H, Rogers K, Sukkar L, Jun M, Kang A, Young T et al. (2020), 'Prevalence, incidence and risk factors of diabetes in Australian adults aged ≥45 years: A cohort study using linked routinely-collected data', Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology, volume 22, doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2020.100240.