Social support

Social support can come in different forms such as:

- instrumental support (help with personal care, household chores, transport or finances)

- emotional support (offering empathy and affection)

- informational support (providing advice and guidance).

Social support is not a one-way relationship; it is built on the ties people have with other individuals, groups, and the broader community (Lin et al. 1979). In addition to receiving support from others, people often provide support to others.

Measures such as social participation and social engagement are commonly used to examine social support. These factors may influence the nature of the social support networks available to older people. Continuing engagement in social and community life is also an important factor in active ageing (WHO 2002).

This page looks at social participation, social engagement and isolation. Throughout this page, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus is specified. The ‘Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this page, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented.

Social participation

Unpaid informal care provision

Some older people are carers, providing informal assistance (help or supervision) to other people, such as those with disability or older people. The 2018 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) estimated there were 647,000 older people (aged 65 and over) providing care. Older carers represented around 1 in 6 (17%) of the total older population and just over half (51%) of older carers had disability (ABS 2019a).

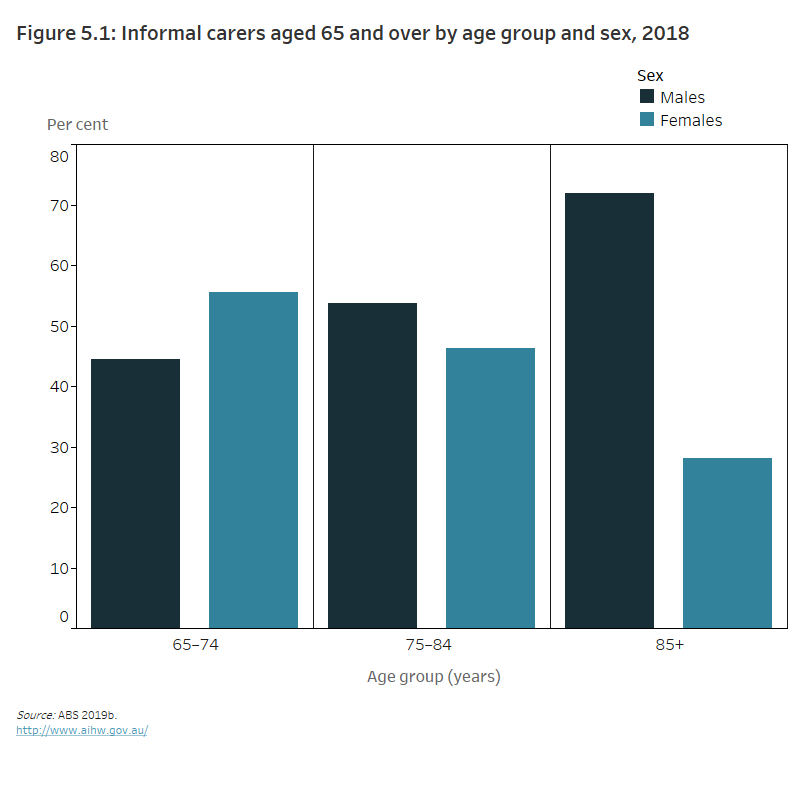

Of carers aged 75–84, 54% (105,000) were men and 45% (88,600) were women. Around 7 in 10 carers aged 85 and over were men (72%, 27,400) and 30% (11,300) were women (AIHW analysis of ABS 2019b) (Figure 5.1). Note this data has been randomly adjusted to avoid the release of confidential data and discrepancies may occur between sums of the component items and totals.

Figure 5.1: Informal carers aged 65 and over by age group and sex, 2018

The column graph shows that in 2018 females constituted a greater proportion of informal carers in Australians aged 65–74 (56%), while males constituted a greater proportion of informal carers in Australians aged 75–84 (54%) and aged over 85 (72%).

Of all older informal carers, over 1 in 3 (35%, 229,000) were primary carers (that is, the carer providing the most informal assistance to a person). Around 6 in 10 (61%) older primary carers were women. Of these older women that were primary carers, 7 in 10 (71%) provided care to their partner, 13% provided care to their child and 11% provided care to their parent (ABS 2019a).

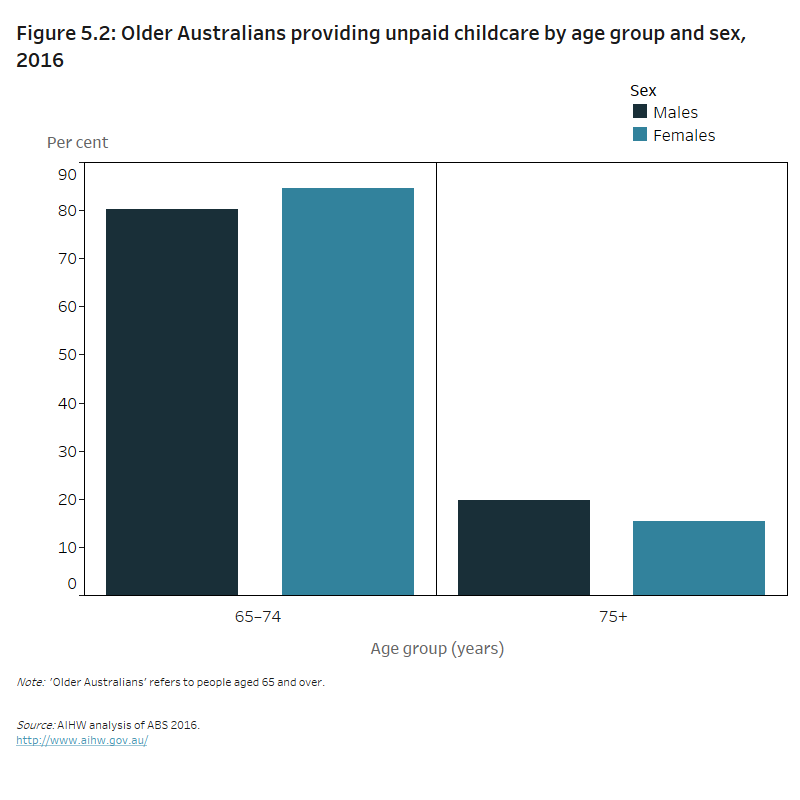

As well as the caring roles described above, older people play an important role in providing unpaid childcare. Data from the 2016 ABS Census showed that 425,000 (13%) older people had spent time in the last 2 weeks caring for a child or children aged under 15 years without being paid. People aged 65–74 (83%) were most likely to provide this care (AIHW analysis of ABS 2016).

Women more commonly provided unpaid child care (61%). However, similar to the provision of other informal care, this differed with increasing age - a higher percentage of men aged 75 and over provided unpaid child care than women (20% compared with 15%, respectively) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2016) (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2: Older Australians providing unpaid childcare by age group and sex, 2016

The column graph shows that in 2016 a large proportion of Australians aged 65–74 provided unpaid childcare. While a greater proportion of women aged 65–74 provided unpaid childcare than men (85% and 80% respectively), a greater proportion of men aged over 75 provided unpaid childcare than women (20% and 15% respectively).

Volunteering

Many older people volunteer formally through an organisation or group, or participate in other informal volunteering. Volunteering may offer an opportunity for activity, social connection and personal satisfaction.

According to the 2019 ABS General Social Survey (GSS), there were an estimated 638,000 (25%) people aged 70 and over who participated in unpaid voluntary work through an organisation in the last 12 months (26% of older women and 23% of older men). Around 1 in 2 (51%) people aged 70 and over who volunteered, volunteered for 100 hours or more in the last 12 months (ABS 2020a).

Many older people also participate in informal volunteering. Just under half (45%) of people aged 70 and over reported having provided unpaid work or support to non-household members in the last 4 weeks (ABS 2020a).

Social engagement and isolation

Many factors may affect people’s ability to participate in society and social activities, such as their health, living arrangements and access to a licence or a vehicle. According to the 2018 SDAC, the majority of older people (aged 65 and over) who were living in households had participated in social activities at home (97%) or outside their home (94%) in the previous 3 months.

In 2018, in the last 3 months:

- Almost 9 in 10 (87%) older people reported visiting relatives or friends away from home.

- 3 in 4 (74%) reported going out with relatives or friends.

- 1 in 3 (33%) reported participating in sport or physical recreation with others.

- Over 1 in 4 (28%) reported going on holiday or camping with others (ABS 2019a).

In 2018, over 3 in 4 older people (77%) living in households had participated in activities in the community in the last 12 months. In particular:

- Around half (49%) of older people had participated in physical activities for exercise or recreation.

- Around half (49%) had attended a movie, concert, theatre or other performing arts event.

- 3 in 10 (30%) had visited a public library.

- 1 in 4 (24%) had visited a museum or art gallery (ABS 2019a).

Family and community support

According to the 2019 GSS, nearly 3 in 4 (73%) people aged 70 and over had face-to-face contact with family or friends living outside the household at least once a week in the last 3 months. Many (84%) had other forms of contact with family or friends living elsewhere. The majority (95%) were able to get support in times of crisis from persons living outside the household (ABS 2020a).

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Australia, physical distancing has been in place to reduce the risk of the virus spreading. This has impacted on social gatherings. At times during the pandemic, all Australians were advised to stay at home, affecting their social engagement and connections with family and friends. Social isolation and loneliness also had major impacts on older people living in residential aged care facilities (see Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety 2020. Aged care and COVID-19: a special report).

Social connectedness

According to the Families in Australia Survey, conducted in 2020 by the Australian Institute of Family Studies – during the COVID-19 pandemic, older people struggled to stay connected with family and friends. For example:

- 23% of those aged over 70 reported having daily contact with family living outside the household, compared with 40% of people aged under 40.

- People aged over 70 were more than twice as likely as people under 40 to have less-than-weekly contact with family living elsewhere (10% compared with 4%, respectively) (Hand et al 2020).

Attendance at social gatherings

The ABS Household Impacts of COVID-19 survey in January 2021 asked whether people had attended one or more social gatherings since 1 December 2020, when many of the restrictions had been eased or lifted. Around 3 in 10 (31%) older people chose not to attend any social gatherings. The majority were comfortable or very comfortable attending social gatherings at their own residence (85%), or at a friend or family member’s residence (85%) (ABS 2021a).

In February 2021, 14% of older people reported having participated in social gatherings of more than 10 people at least once a week in the last 4 weeks. In March 2020, before COVID-19 restrictions began, 1 in 4 (26%) older people reported having participated (ABS 2021b).

Loneliness

Loneliness is a feeling of distress people experience when their social relationships are not the way they would like (APS 2018), and may affect health and wellbeing. Studies investigating loneliness across age groups can have contradictory findings (AIHW 2021). While some studies find higher levels of loneliness among older people (Relationships Australia 2018), others find lower levels (Relationships Australia 2011).

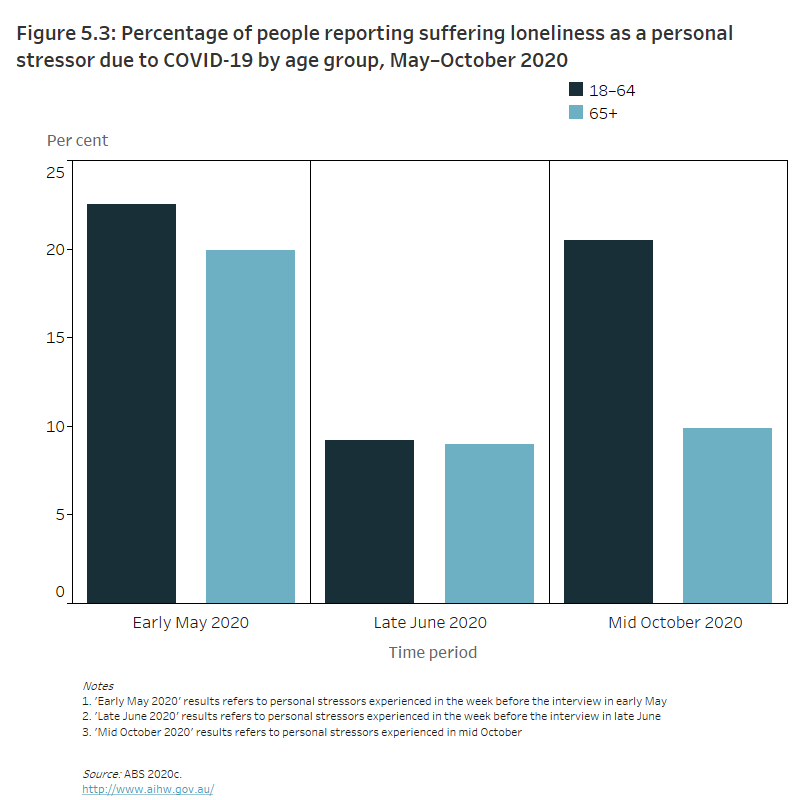

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with younger people (aged 18–64), older people were less lonely (APS 2018). During the pandemic, loneliness remained the most commonly reported personal stressor due to COVID-19. In May 2020, not long after the social distancing requirements had been in place, loneliness was reported as a personal stressor experienced in the last 4 weeks due to COVID-19 for around 1 in 5 (20%) older people and 1 in 4 (23%) younger people (ABS 2020b). Later in the pandemic in October 2020, 1 in 10 (10%) older people reported loneliness and 1 in 5 (21%) younger people reported loneliness (ABS 2020c) (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3: Proportion of persons reporting suffering loneliness as a personal stressor due to COVID-19 by age, May–October 2020

The column graph shows that the proportion of older Australians who reported experiencing loneliness fluctuated throughout 2020 as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Reports of loneliness in the last four weeks among older Australians was highest in May (20%). Although the proportion of older Australians reporting loneliness decreased in June and October, loneliness reports remained at 9% and 10% respectively.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2016. Microdata: Census of Population and Housing, 2016. ABS cat. no. 2037.0.30.001. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2019a. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018. ABS cat. no. 4430. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2019b. Microdata: Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, 2018. ABS cat. no. 4430.0.30.002. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2020a. General Social Survey: Summary Results, Australia. ABS cat. no.4159. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2020b. Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, May 2020. ABS cat. no.4940. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2020c. Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, October 2020.. ABS cat. no.4940. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2021a. Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, January 2021. ABS cat. no. 4940. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2021b. Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, February 2021. ABS cat. no.4940. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2021. Australia’s welfare 2021: snapshots. Social isolation and loneliness. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

APS (Australian Psychological Society) 2018. Australian loneliness report: A survey exploring the loneliness levels of Australians and the impact on their health and wellbeing. Viewed 2021.

Hand K, Carroll M, Budinski M and Baxter J 2020. Families in Australia Survey: Life during COVID-19 Report no. 2: Staying connected when we're apart. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 2021.

Lin N, Simeone R, Ensel W and Kuo W 1979. Social support, stressful life events, and illness: a model and an empirical test. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 20:108–19. Viewed 2021.

Relationships Australia 2011. Issues and concerns for Australian relationships today: Relationships Indicators Survey 2011. Canberra: Relationships Australia. Viewed 2021.

Relationships Australia 2018. Is Australia experiencing an epidemic of loneliness? Findings from 16 waves of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics of Australia Survey. Canberra: Relationships Australia. Viewed 2021.

WHO (World Health Organization) 2002. Active ageing: A policy framework. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 2021.