Social isolation and loneliness

Loneliness and social isolation were concerns before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic but have been exacerbated in the subsequent years.

In 2022, males aged 15–24 tended to experience more social isolation and loneliness than females.

Social isolation and loneliness are among the many factors that can be detrimental to a person’s wellbeing.

Social isolation and loneliness can harm both mental and physical health and may affect life satisfaction. They are concerning issues in Australia due to the impact they have on peoples’ lives and wellbeing.

Loneliness has been linked to premature death, poor physical and mental health (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015), greater psychological distress (Manera et al. 2022) and general dissatisfaction with life (Schumaker et al. 1993). Loneliness among Australians was already a concerning issue before the COVID-19 pandemic, to the extent that in 2022 it has been described as one of the most pressing public health priorities in Australia (Ending Loneliness Together 2022).

Social isolation has been linked to mental illness, emotional distress, suicide, the development of dementia, premature death and poor health behaviours (smoking, physical inactivity and poor sleep) – as well as biological effects, including high blood pressure and impaired immune function (Cacioppo et al. 2002 and Grant et al. 2009 in Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015). Social isolation is also associated with psychological distress (Manera et al. 2022) and sustained decreases in feelings of wellbeing (Shankar et al. 2015). Conversely, more frequent social contact is associated with better overall health (Botha 2022).

The difference between social isolation and loneliness

Social isolation ‘means having objectively few social relationships or roles and infrequent social contact’ (Badcock et al. 2022:7). It differs from loneliness, which is a ‘subjective unpleasant or distressing feeling of a lack of connection to other people, along with a desire for more, or more satisfying, social relationships’ (Badcock et al. 2022:7). The 2 concepts may, but do not necessarily, coexist (Badcock et al. 2022; Relationships Australia 2018) – a person may be socially isolated but not lonely, or socially connected but feel lonely.

Who experiences social isolation and loneliness?

Social isolation

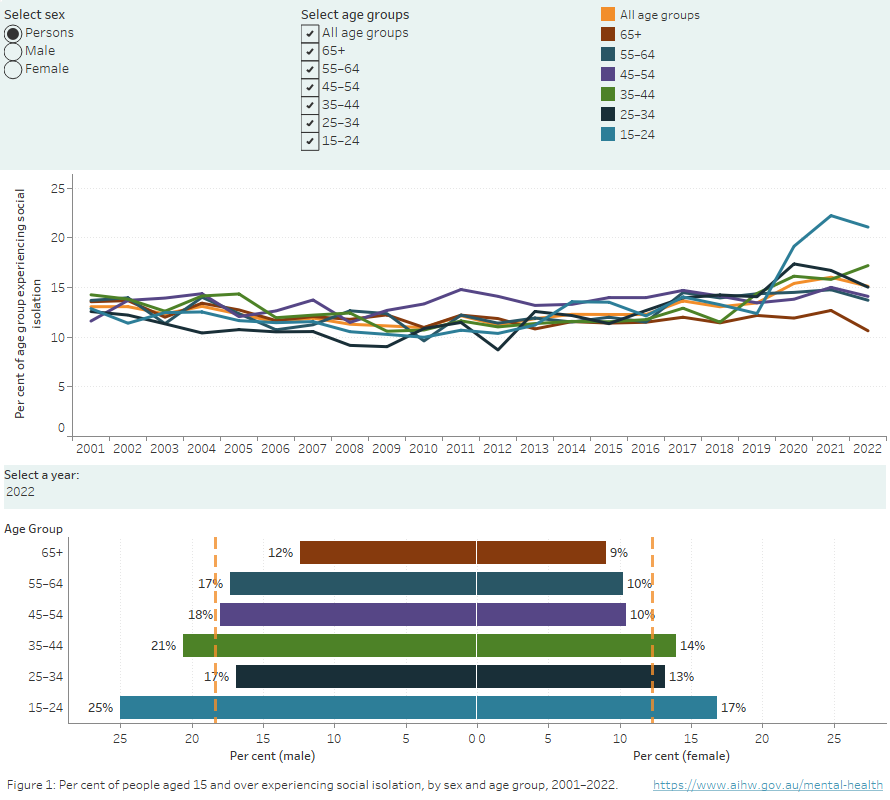

In 2022, almost 1 in 7 (15%) Australians (18% of males and 12% of females) were experiencing social isolation. Compared to just before the pandemic (2019) the proportion of young people aged 15–24 experiencing social isolation increased markedly over 2020 and 2021. During the later years of the pandemic (2021 to 2022) the proportion of young females (15–24 years) experiencing social isolation decreased (23% in 2021 down to 17% in 2022), while the proportion of young males continued to increase (from 22% to 25% over this time). The 35–44 year age group was the only one for whom social isolation continued to increase from 2021 (16% in 2021 to 17% in 2022) (Figure SIL.1).

Figure SIL 1: How has social isolation changed over time?

Line graph and butterfly chart showing the per cent of males and females of various age groups experiencing social isolation, from 2001 to 2022. The proportion of males aged 15–24 experiencing social isolation from 2001 to 2019 remained relatively steady between 11% and 15%, before increasing to 19% in 2020 and continuing to increase to 22% in 2021, then dropped to 21% in 2022.

Source: AIHW analysis of Household and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) data, waves 1–22.

Loneliness

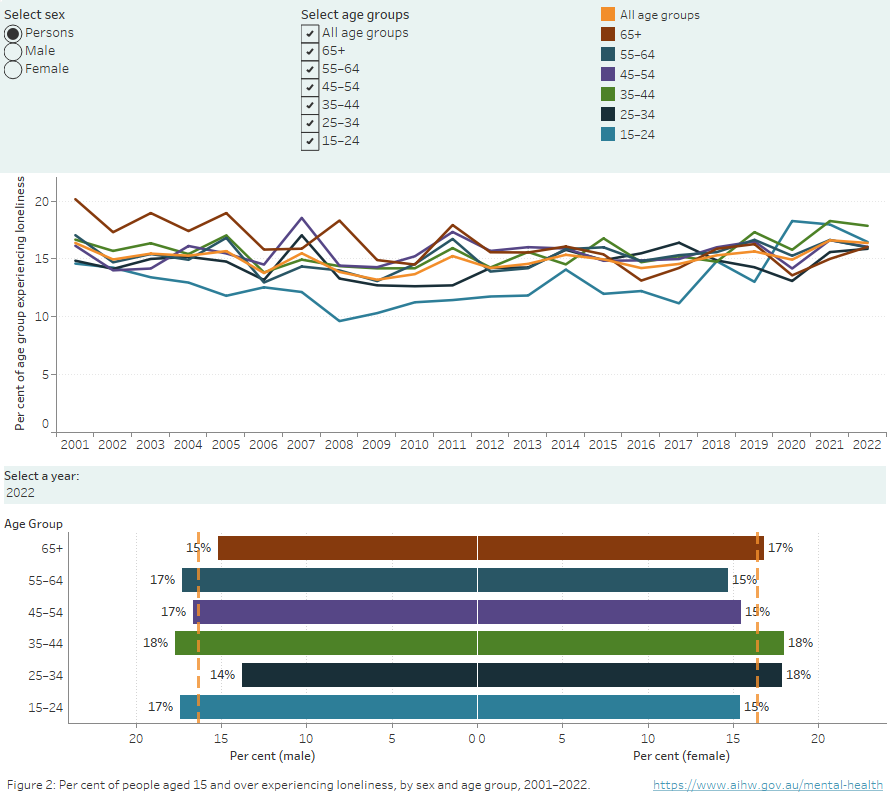

In 2022, just over 1 in 6 (16%) Australians were experiencing loneliness. As of 2022, about 1 in 5 (17%) males and 1 in 6 (15%) females aged 15–24 were experiencing loneliness. An increasing number of people aged 15–24, have reported experiencing loneliness since 2012. In contrast, the frequency of people aged 65 and over reporting loneliness has been steadily declining since 2001 (Figure SIL 2).

Figure SIL 2: Per cent of people aged 15 and over experiencing loneliness, by sex and age group, 2001–2022

Line graph and butterfly chart showing the per cent of males and females of various age groups experiencing loneliness, from 2001 to 2022. In 2001, 15% of people aged 15–24 were lonely, compared to 16% in 2022. The proportion of people aged 65 and over who are lonely has decreased from 20% in 2001 to 16% in 2022.

Source: AIHW analysis of Household and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) data, waves 1–22.

Australia’s available data on loneliness do not allow for reliable international comparisons. In a recent systematic review of loneliness in 113 countries led by Australian researchers, Australian data could not be compared with those of other countries due to a lack of comparable prevalence data – except for the adolescent age group (Surkalim et al. 2022). To date, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has not reported comparable data for Australia on its measures of ‘people feeling lonely’ and ‘people feeling left out of society’ (OECD 2022, 2023).

Domestic and family violence

Family, domestic and sexual violence is a major health and welfare issue in Australia, occurring across all socioeconomic and demographic groups, but predominantly affecting women and children (AIHW 2022).

Social isolation is a well-recognised tactic of coercive control used by perpetrators to control their victims (Boxall and Morgan 2021). It ensures the victim does not hear other people’s perspectives: perpetrators control the information the victim receives, reduce their help-seeking opportunities, and control the victim’s ability to leave the abusive relationship (Stark 2007). Recent studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Australians are identifying some adverse outcomes of stay-at-home orders associated with increased social isolation that put some women and children at higher risk of experiencing family violence (Morgan and Boxall 2020; Pfitzner et al. 2022).

An online survey of 166 practitioners conducted in Victoria during the 2020 lockdowns revealed that women’s experiences of intimate partner violence worsened because of their increased social isolation, which reduced their ability to seek external help and support (Pfitzner et al. 2022). This trend was also identified in other cities and countries, with perpetrators using the social isolation provided by the stay-at-home orders to increase abusive behaviours towards victims within their homes (Piquero et al. 2021). An Australian study suggests the combination of increased social isolation and economic stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic did increase the risks of domestic and family violence for women in current cohabiting relationships (Morgan and Boxall 2020).

For more information, refer to Family, domestic and sexual violence.

Preventing and reducing social isolation and loneliness

Engaging in volunteer work and maintaining active memberships of sporting or community organisations are also associated with reduced social isolation (Flood 2005). Participating in paid work and caring for others have been proposed as safeguards against loneliness. However, it is unclear whether community engagement can consistently act as a protective factor against loneliness. For example:

- one study found that loneliness is lower in people who spend at least some time each week volunteering (Flood 2005)

- another study found no relationship between loneliness and volunteering, or between loneliness and socialising and participating in sport and community organisations (Baker 2012).

For people aged 25 to 44, being in a relationship is a greater protective factor against loneliness for men than for women (Baker 2012). Women living with others and women living alone report similar levels of loneliness, while men living alone report higher levels of loneliness than men living with others (Flood 2005).

The role of social media

Whether social media has potential benefits or negative impacts on people’s experiences of social isolation has been discussed since the advent of this medium. There is no straightforward relationship however, between social media use and experiences of social isolation and loneliness, whether positive or negative.

Researchers have identified some positive impacts of how social media can help people feel socially connected, especially adolescents (aged 11–19) who are looking for peers online to boost their psychosocial wellbeing, discuss identity development and encourage a sense of belonging (Allen et al. 2014). Other research has showed that using social media benefited young people (aged under 21) who experienced higher levels of social anxiety by increasing their ability to socialise, reducing their feelings of social isolation (Lin et al. 2017).

Even though adolescents can use social media to create supportive communities, research shows that the relationship between its use and loneliness can work both ways. When it is used to escape physical social interactions, feelings of loneliness were found to increase. People experiencing loneliness may benefit from external support with the use of the Internet to ensure they engage in existing friendships and learn how to develop new ones online to reduce feelings of loneliness and social isolation (Nowland et al. 2017).

More research has emerged since the pandemic started that investigates the use of social media by people of all ages and their experiences of social isolation, but findings are not always positive. For example, a study of people living in Norway, the United States of America, the United Kingdom and Australia looked at the impact of people’s use of social media during the pandemic. The researchers found an association between emotional distress and more frequent use of social media (Geirdal et al. 2021).

Another international study investigating current research between online social networking and mental health outcomes for people aged 50 and over found that social media enhanced communication with family and friends, provided greater independence and self-efficacy, aided in the creation of new communities online, helped to form positive associations with wellbeing and life satisfaction, and was associated with decreased depressive symptoms (Chen et al. 2021).

As more studies are conducted through the pandemic and beyond, an understanding of how social media affects feelings of social isolation and loneliness may become clearer.

Although social isolation and loneliness are now well-recognised public health concerns, major gaps remain in understanding what works to resolve them (Smith and Lim 2020). Due to our diverse social needs, preferences and resources, there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution (Ending Loneliness Together 2022).

Companion animals

Pets can play an integral part in people’s lives, regardless of the person’s culture, profession or age. Companion animals are one source of external support that can bring both physical and mental health benefits (Brooks et al. 2016). All types of companion animals may contribute to reducing social isolation and feelings of loneliness (Brooks et al. 2018; Kretzler et al. 2022).

Multiple studies have found an association between pet ownership and lower experiences of social isolation, particularly for children (Christian et al. 2020; Hartwig and Signal 2020; Kretzler et al. 2022). Further, research suggests that companion animals may positively influence experiences for older people (aged 60 and over) by increasing their sense of purpose and meaning, facilitating increased social interaction, reducing loneliness and improving emotional resilience (Gan et al. 2019), as well as being potentially a protective factor against suicide (Young et al. 2020a). Owning a pet increases the opportunity for people to get to know their neighbours and for social interactions and forming friendships (Wood et al. 2015).

Brooks and colleagues (2018) systematically reviewed 17 studies that investigated the relationship between companion animals, specifically domestic animals, and the assistance these animals provided in helping people to manage their mental health conditions. The quantitative studies produced mixed findings, with people experiencing positive, negative and neutral impacts of their companion animal on their personal mental health.

Qualitative studies suggest, however, that people with mental health conditions may benefit from the direct support their companion animals provide. This support includes helping their owners to manage their mental health condition, reducing people’s stress and regulating emotions – particularly beneficial during times of crisis, improving people’s quality of life, providing a consistent source of comfort, and aiding social and community interactions. Companion animals were found to help mitigate feelings of social isolation and loneliness by providing physical warmth and companionship, and opportunities for non-judgemental communication for their owners. Further, they may offer a distraction or disruption when their owners experience panic attacks and other symptoms of mental illness (Brooks et al. 2018). On the other hand, negative impacts included difficulties with the daily commitment of pet ownership and the psychological stress when losing a companion pet.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, studies have mostly shown that the association between pet ownership, loneliness and social isolation has strengthened (Kretzler et al. 2022). One study found that cats gave people an outlet for stress through the strong bonds they had established with owners, and the affection and comfort they provided, thus acting as a buffer to the social isolation created by the lockdowns (Currin-McCulloch et al. 2021). Dogs provided people with daily reinforcement of positive behaviours such as routine, exercise and play, which all contributed to decreased feelings of social isolation (Bussolari et al. 2021).

It is not yet clear whether this strong relationship between people and their pets at the levels seen in the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic will persist in the future (Hughes et al. 2021; Young et al. 2020b).

Where can I go for more information?

For more information about social isolation and loneliness, see:

AIHW (Australia Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022) Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia, AIHW website, accessed 9 February 2024.

Allen KA, Ryan T, Gray DL, McInerney DM and Waters L (2014) ‘Social media use and social connectedness in adolescents: the positives and potential pitfalls’, The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 31(1):18–31, doi:10.1017/edp.2014.2, accessed 9 February 2024.

Badcock JC, Holt-Lunstad J, Garcia E, Bombaci P and Lim MH (2022) Position statements on addressing social isolation and loneliness and the power of human connection, Global Initiative on Loneliness and Connection, accessed 9 February 2024.

Baker D (2012) All the lonely people: loneliness in Australia, 2001–2009, The Australia Institute, Canberra, Institute paper no. 9, accessed 9 February 2024.

Botha F (2022) ‘Social connection and social support’, in Wilkins et al., The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: selected findings from waves 1 to 20, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research, Melbourne.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021) Statistical Bulletin 30 – experiences of coercive control among Australian women, Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra.

Brooks HL, Rushton K, Lovell K, Bee P, Walker L, Grant L and Rogers A (2018) ‘The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence’, BMC Psychiatry, 18(31), doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1613-2, accessed 9 February 2024.

Brooks H, Rushton K, Walker S, Lovell K and Roger A (2016) ‘Ontological security and connectivity provided by pets: a study in the self-management of the everyday lives of people diagnosed with a long-term mental health condition’, BMC Psychiatry, 16(409), doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1111-3, accessed 9 February 2024.

Bussolari C, Currin-McCulloch J, Packman W, Kogan L and Erdman P (2021) ‘“I couldn’t have asked for a better quarantine partner!”: experiences with companion dogs during Covid-19’, Animals, 11(2):330, doi:10.3390/ani11020330.

Chen E, Wood D and Ysseldyk R (2021) ‘Online social networking and mental health among older adults: a scoping review’, Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 41(1):26–39, doi:10.1017/S0714980821000040.

Christian H, Mitrou F, Cunneen R and Zubrick SR (2020) ‘Pets are associated with fewer peer problems and emotional symptoms, and better prosocial behaviour: findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children’, The Journal of Paediatrics, 220:200–206, doi:10.1016/j.peds.2020.01.012.

Currin-McCulloch J, Bussolari C, Packman W, Kogan L and Erdman P (2021) ‘Grounded by purrs and petting: experiences with companion cats during Covid-19’, Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, doi:10.1079/hai.2021.0009.

Ending Loneliness Together (2022) Social connection to accelerate social recovery white paper, WayAhead, Sydney, accessed 9 February 2024.

Flood M (2005) Mapping loneliness in Australia, The Australia Institute, Canberra, accessed 9 February 2024.

Gan GZH, Hill A, Yeung P, Keesing S and Netto JA (2019) ‘Pet ownership and its influence on mental health in older adults’, Aging and Mental Health, 24(10), 1605–1612, doi:10.1080/13607863.2019.1633620, accessed 9 February 2024.

Geirdal AO, Ruffolo M, Leung J, Thygesen H, Price D, Bonsaksen T and Schoultz M (2021) ‘Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study’, Journal of Mental Health, 30(2):148–155, doi:10.1080/09638237.2021.1875413, accessed 9 February 2024.

Hartwig E and Signal T (2020) ‘Attachment to companion animals and loneliness in Australian adolescents’, Australian Journal of Psychology, 72(4):337–346, doi:10.1111/ajpy.12293, accessed 9 February 2024.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T and Stephenson D (2015) ‘Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review’, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2):227–237, doi:10.1177/1745691614568352, accessed 9 February 2024.

Hughes AM, Braun L, Putnam A, Martinez D and Fine A (2021) ‘Advancing human-animal interaction to counter social isolation and loneliness in the time of Covid-19: a model for an interdisciplinary public health consortium’, Animals, 11(8):2325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082325, accessed 9 February 2024.

Kretzler B, Konig H and Hajek A (2022) ‘Pet ownership, loneliness, and social isolation: a systematic review’, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57:1935–1957, doi 10.1007/s00127-022-02332-9, accessed 9 February 2024.

Manera KE, Smith BJ, Owen KB, Phongsavan P and Lim MH (2022) ‘Psychometric assessment of scales for measuring loneliness and social isolation: an analysis of the household, income and labour dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey’, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20:40, doi:10.1186/s12955-022-01946-6, accessed 9 February 2024.

Morgan P and Boxall H (2020) ‘Social isolation, time spent at home, financial stress and domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 609, Australian Institute of Criminology, Australian Government, Canberra.

Nowland R, Necka EA and Cacioppo J (2017) ‘Loneliness and social Internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world?’, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), doi:10.1177/1745691617713052, accessed 9 February 2024.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2022) COVID-19 and well-being: life in the pandemic – Australia, OECD website, accessed 9 February 2024.

OECD (2023) Measuring well-being and progress: well-being research, OECD website, accessed 9 February 2024.

Pfitzner N, Fitz-Gibbon K and True J (2022) ‘When staying home isn’t safe: Australian practitioner experiences of responding to intimate partner violence during COVID-19 restrictions’, Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 6(2):297–314, accessed 9 February 2024.

Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Jemison E, Kaukinen C and Knaul FM (2021) ‘Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, doi:10.1016/j.crimjus.2021.101806, accessed 9 February 2024.

Relationships Australia (2018) Is Australia experiencing an epidemic of loneliness? Findings from 16 waves of the Household Income and Labour Dynamics of Australia Survey, Relationships Australia website, accessed 9 February 2024.

Schumaker JF, Shea JD, Monfries MM and Growth-Marnat G (1993) ‘Loneliness and life satisfaction in Japan and Australia’, Journal of Psychology, 127(1):65–71.

Shankar A, Rafnsson SB and Steptoe A (2015) ‘Longitudinal associations between social connections and subjective wellbeing in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing’, Psychology & Health, 30(6):686–698, doi:10.1080/08870446.2014.979823, accessed 9 February 2024.

Smith B and Lim M (2020) ‘How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation’, Public Health Research & Practice, 30(2):e3022008.

Stark E (2007) Coercive control: how men entrap women in personal life, Oxford University Press, New York.

Surkalim DL, Luo M, Eres R, Gebel K, van Buskirk J, Bauman A and Ding D (2022) ‘The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis’, BMJ, 376:e067068, doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-067068, accessed 9 February 2024.

Wood L, Martin K, Christian H, Nathan A, Lauritsen C, Houghton S, Kawachi I and McCune S (2015) ‘The pet factor – companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support’ PLoS ONE, 10(4), doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122085, accessed 9 February 2024.

Young J, Bowen-Salter H, O’Dwyer L, Stevens K, Nottle C and Baker A (2020a) ‘A qualitative analysis of pets as suicide protection for older people’, Anthrozoos, 33(2), 191–205, doi:10.1080/08927936.2020.1719759, accessed 9 February 2024.

Young J, Pritchard R, Nottle C and Banwell H (2020b) ‘Pets, touch, and COVID-19: health benefits from non-human touch through times of stress’, Journal of Behavioural Economics for Policy, 4(2), 25–33.

Data on this page cover years 2001 to 2022. This page was last updated in April 2024.