Health – risk factors

Some behaviours and risk factors (attributes, characteristics or exposures) can increase the likelihood of developing a disease or health condition. They include behavioural risk factors (which are those that individuals have the most ability to modify) and biomedical risk factors (bodily states). Behavioural and biomedical risk factors can increase each other’s effects when they occur together in an individual (AIHW 2016a). People can also experience other risk factors that affect their health and wellbeing, such as social isolation, poor engagement and exclusion. For information on these topics, see Social support.

Throughout this page, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus is specified. The ‘Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this page, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented.

Many serious health issues, including some chronic diseases (such as cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, certain types of cancer, type 2 diabetes, influenza and high blood pressure) can relate to these behaviours and risk factors (Table 3C.1).

| 18-64 | 64+ | |

|---|---|---|

|

Met guidelines for physical activity (a) |

17.0 |

18.3 |

|

Not a current smoker |

83.0 |

92.6 |

|

Vaccinated against influenza |

22.8 |

74.6 |

|

Did not exceed guidelines for alcohol consumption(b) |

51.1 |

79.9 |

|

Met recommendation for fruit and vegetables(c) |

4.7 |

8.2 |

|

Normal weight range(d) |

33.7 |

23.5 |

|

Did not experience high levels of psychological distress(e) |

81.9 |

86.2 |

Notes:

(a) Met the 2014 Physical activity guidelines based on Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines for any physical activity.

(b) Refers to single-occasion risk on any occasion in the last 12 months. See ‘Risky drinking levels’ box below for more information.

(c) Met the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2013 Australian Dietary Guidelines recommendation for daily consumption of fruit and vegetables.

(d) Based on measured height and weight and includes a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5 to less than 25.

(e) Did not experience high/very high psychological distress. Denominator includes level of distress unable to be determined.

Sources: ABS 2018c; AIHW 2011.

Physical activity

Regular physical activity has important benefits for both physical and mental health, including:

- reducing the risk of many health problems, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, anxiety, depression and musculoskeletal problems

- enhancing social and community connectedness by providing opportunities for social engagement (AIHW 2020e).

According to the 2017–18 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS), 7 in 10 (73%) people aged 65 years and over engaged in some form of exercise in the last week, but many older people (82%) did not meet the guidelines for physical activity (defined as accumulating at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on most, preferably all, days; see box below for more information). Similarly, 83% of people aged 18–64 did not meet the guidelines (ABS 2018c).

Around one quarter (26%) of older people (aged 65 and over) engaged in 30 minutes or more of exercise on 5 or more days in the last week (28% of older men and 25% of older women), with:

- 30% of those aged 65–74

- 23% of those aged 75–84

- 11% of those aged 85 and over (ABS 2018c).

Not meeting the physical activity guidelines

Some 82% of older Australians (aged 65 and over) did not meet the physical activity guidelines. However, within this group, a range of behaviours are represented, with some falling further below the recommended level of physical activity than others:

- 4 in 10 (42%) men and almost half (47%) of women completed less than 30 minutes of exercise in the last week.

- At the other end of the spectrum, 47% of men and 38% of women completed 150 minutes or more of exercise in the last week.

Some of the people who did not meet the physical activity guidelines reported no physical activity at all. In all, an estimated 983,000 people aged 65 and over did no physical activity in the last week, representing 38% of older Australians who did not meet the physical activity guidelines. For people aged 18–64 who did not meet the physical activity guidelines in the last week, 23% did no physical activity in the last week (AIHW 2020e).

Nutrition

A healthy diet can help to prevent and manage many chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some forms of cancer. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC 2013) recommends a minimum number of serves of fruit and vegetable every day for a healthy lifestyle, with the number of serves based on a person’s age and sex.

Based on data from the 2017–18 NHS, across all age groups, most Australians (95%) reported not eating enough fruit and vegetables to meet these recommended guidelines. Around 1 in 12 older Australians (8.2%) met both the fruit and vegetable guidelines (10% of older women and 6.1% of older men). Over 3 in 5 (63%) older Australians met the recommended fruit intake, while few (11%) met this for vegetables (ABS 2018c).

Obesity

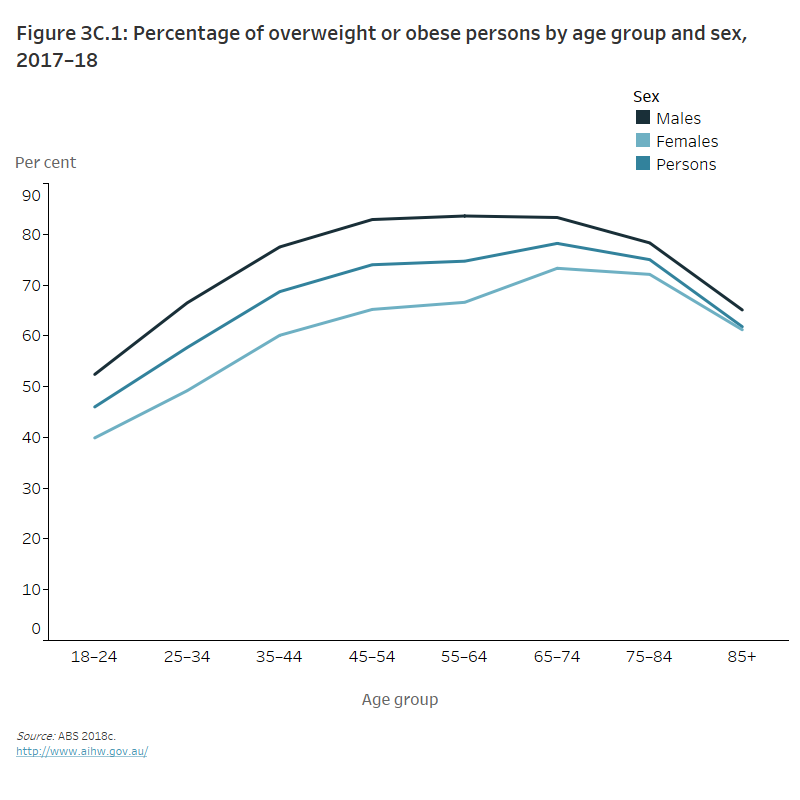

Obesity is a key health issue for older Australians and can increase the risk of developing long-term health conditions such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and certain cancers. Based on estimates from the 2017–18 NHS, 3 in 4 (76%) older Australians (aged 65 and over) were overweight or obese. The prevalence of overweight or obesity increases with age up to the 65–74 age group. In 2017–18, 78% of people in this age group were overweight or obese, compared with 65% of those aged 18–64 years (AIHW 2020g) (Figure 3C.1).

Figure 3C.1: Percentage of overweight or obese persons by age group and sex, 2017–18

The line graph shows that the percentage of overweight and obese men peaked in those aged 55–64, compared with women who peaked in the 65–74 age group (84% and 73%, respectively). The percentage of overweight and obese persons was greater in men across all age groups compared with women.

Tobacco smoking

Tobacco is one of the leading risk factors contributing to the burden of disease for older Australians. Specifically, tobacco is the leading risk factor for the burden of disease for males and females aged 65–74 and 75–84, and males aged 45–64 (AIHW 2020a). It is the leading risk factor for coronary heart disease and lung disease and contributes to cancer deaths (see Australia’s health 2020: Tobacco smoking snapshot).

According to the 2017–18 NHS, an estimated 251,700 (7%) older Australians (aged 65 and over) were current daily smokers. Almost half of older people had never smoked (49%) and around 2 in 5 (44%) were ex-smokers (ABS 2018c).

Improved awareness of the negative health effects of tobacco, and a range of control measures aimed at reducing smoking rates, may be influencing overall declines in smoking rates. The National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) estimated that the daily smoking rate across all ages (14 and over) has declined from just over 12% in 2016 to 11% in 2019, and halving since 1991 (24%). However, the move away from smoking is not consistent across all age groups. According to the NDSHS, older people were some of the most likely to smoke daily. Of all daily smokers aged 14 and above in 2019, 2 in 5 (39%) were aged 50 and over. This was an increase from 2001 where people aged 50 and over made up nearly 1 in 4 (23%) of all daily smokers aged 14 and above. People aged 60 and over made up 8.9% of all daily smokers in 2001, doubling in 2019 to 18% (AIHW 2020f).

Older people in the NDSHS

Most population data define ‘old’ as persons aged 65 and over to align with the qualifying age for the Age pension. However, AIHW reporting on the NDSHS generally refers to older people as those aged 50 and over. This wider age range is to capture people who may be ageing prematurely due to alcohol and other drug use, and to include the ‘baby boomer’ cohort (AIHW 2016b). On this page, people in their 50s are included in some sections where the NDSHS is being referenced. The age cohort relevant to the information presented has been specified to make this clear.

In 2019, the proportion of daily smokers who were aged:

- in their 50s was 16%

- in their 60s was 11%

- 70 and over was 4.6% (decreasing from 6.0% in 2016) (AIHW 2020f).

Compared with younger smokers, older smokers were:

- more likely to report smoking more cigarettes. People in their 60s smoked 16.5 cigarettes per day on average, and those aged 70 and over smoked 15.5 cigarettes. This was around double the number of cigarettes smoked by people aged 18–24 (8.1 cigarettes)

- less likely to have intentions to quit smoking. The proportion of current smokers who were not planning to quit smoking was higher among people in their 50s (33%), 60s (40%) and aged 70 and over (46%) compared with all current smokers (30%). The main reason older smokers gave for not wanting to quit was because they enjoyed it (AIHW 2020f).

Alcohol consumption

In Australia, alcohol plays a prominent role in society and is associated with many social and cultural activities. While fewer people are drinking daily and most Australians drink at light to moderate levels, it is excessive drinking that is of most concern. Consuming excessive amounts of alcohol is a health risk. It can contribute to long-term health issues such as liver disease, some cancers and brain damage. In 2019, people aged 55 and over had the highest age-specific rates of alcohol-induced and alcohol-related deaths. Alcohol-induced deaths per 100,00 population were:

- 12.2 for those 55–59

- 13.4 for those aged 60–64

- 11.4 for those aged 65 and over.

The lowest rates of alcohol-induced deaths were for young people aged 15–19 with no alcohol-induced deaths, followed by 0.3 per 100,00 population for people aged 20–24 and 25–29.

The rate of alcohol-related deaths (per 100,000 population) increased with increasing age up to ages 60–64, where it peaked and then dropped for people aged 65 and over:

- 34.3 for those 55–59

- 37.7 for those aged 60–64

- 32.2 for those aged 65 and over.

The lowest rate of 4.2 per 100,000 population was for people aged 15–19 (AIHW 2021a).

Risky drinking levels

New Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol were released in December 2020 (NHMRC 2020). Data for alcohol risk on this page are measured against the 2009 guidelines (NHMRC 2009).

Based on the 2009 Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol, these 2 guidelines are used to measure risk among adults:

- Lifetime risk – for healthy men and women, drinking no more than 2 standard drinks on any day reduces the lifetime risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury.

- Single occasion risk – for healthy men and women, drinking no more than 4 standard drinks on any one occasion.

See National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019 for more information. NDSHS data relating to the updated guidelines are available.

According to 2017–18 NHS estimates, almost 1 in 5 (18%) older Australians (aged 65 and over) exceeded the single occasion risk guideline for alcohol consumption for any occasion in the last 12 months (ABS 2018c).

Data from the 2019 NDSHS indicated that the proportion of people in their 50s giving up alcohol has not changed; 9.1% were ex-drinkers in 2001 and a similar proportion (9.6%) were ex-drinkers in 2019. People aged 60 and over were slightly more likely to have given up alcohol in 2019 (14%) than in 2001 (12%) (AIHW 2020f).

Estimates from the NDSHS showed that, in 2019:

- Among people in their 50s, there has been no change in the proportion of people exceeding the lifetime risk guideline – 22% in 2001 and 21% in 2019. The proportion exceeding the single occasion risk guidelines at least monthly increased from 22% in 2001 to 27% in 2019.

- Around 1 in 6 (17%) people in their 60s exceeded single occasion risk guidelines at least monthly in 2019.

- People aged 70 and over continued to be the most likely to drink daily (13%), followed by people in their 60s (9.6%). While those 70 and over were the least likely age group to exceed single occasion risk guidelines at least monthly (8.8%), this figure increased since 2016 (7.2%) (AIHW 2020f).

Illicit drugs

Illicit drug use includes the use of illegal drugs, use of pharmaceuticals for non-medical purposes and volatile substances used inappropriately (for example, petrol as an inhalant). The most common illicit drugs used are cannabis and non-medical use of pharmaceuticals (AIHW 2020f).

There is an ageing cohort of people who use illicit drugs. Data from the 2019 NDSHS indicate that a greater proportion of older Australians reported illicit drug use than in previous years (AIHW 2020f). Recent (in the previous 12 months) illicit drug use increased among those aged 60 and over, from 3.9% in 2001 to 7.2% in 2019.

The proportion of people aged 60 or over who had used illicit drugs in their lifetime increased between 2016 (26%) and 2019 (29%). There were increases for both men (from 30% to 34%) and women (22% to 24%) (AIHW 2020f).

Recent cannabis use has increased for older people. Between 2016 and 2019, recent use of cannabis significantly increased among people in their 50s (from 7.2% to 9.2%) and those aged 60 and over (from 1.9% to 2.9%). Older people are more likely to use cannabis for medical purposes. In 2019, 43.1% of people who had recently used cannabis for medical purposes only were aged 50 and over, compared with 16.0% of people who had recently used cannabis for non-medical purposes aged 50 and over (AIHW 2020f).

Stress

Chronic stress can potentially lead to anxiety and depression, as well as to physical health issues such as high blood pressure. Chronic stress may be precipitated by experiencing personal stressors, including serious illness or accident, death of a family member or friend, and exposure to abuse. While chronic stress is an independent health risk factor, it may result in psychological distress, which can produce further symptoms (AIHW 2020d).

The 2020 ABS General Social Survey estimated that over half (56%, 1.5 million) of older Australians aged 70 and over had experienced at least one personal stressor in the last 12 months (ABS 2021).

The 2017–18 NHS also provided a measure of stress, using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). The K10 is a scale of non-specific distress. Just under 10% (357,100) of people aged 65 and over reported high or very high levels of psychological distress. Around 1 in 10 older women (11%) and older men (8.9%) reported having high or very high levels of psychological distress (ABS 2018c). For information on mental health conditions among older people, see Health—selected conditions.

Vaccination

Vaccination is the process of receiving a vaccine. It is a safe and effective way to protect individuals against harmful communicable diseases, while also preventing the spread of these diseases in the community. Vaccine-preventable illnesses that can seriously affect the health of older Australians include influenza, pneumonia and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). These vaccines are free for people aged 65 and over to ensure high coverage. The influenza vaccine is recommended annually; the pneumonia vaccine is administered less often.

It is difficult to estimate the number of Australians vaccinated against influenza because vaccinations can also be purchased by workplaces or individuals, in addition to programs funded by governments; see Key data gaps.

Preventing influenza and COVID-19

Influenza is a contagious respiratory disease that causes seasonal epidemics in Australia. It spreads from person to person through droplets made when an infected person coughs, sneezes or speaks.

Between 1997 and 2019, influenza caused just over 4,800 deaths in Australia, of which 85% (4,100 deaths) were in people aged 65 and over (AIHW 2021c). These data may underestimate the real impact of influenza on deaths in Australia, as many of the people who die will not have been tested for influenza (AIHW 2020c).

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a reduction in influenza cases. It could be that the reduction was the result of social distancing measures taken to reduce COVID-19. It is also possible that the increased uptake of influenza immunisation played a role (AIHW 2020b).

In March 2021, Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout began. Vaccines were rolled out in phases, being made available first to those most in need of protection. These priority groups were identified based on expert medical advice. Residential aged care residents and workers could receive a COVID-19 vaccine from the first phase of the rollout (Phase 1a) (Department of Health 2021b). At 13 October 2021, nearly 32 million vaccine doses had been administered Australia wide. Around 2,600 residential aged care facilities had been visited. In total, just over 1 million doses had been administered in aged care and disability facilities (Department of Health 2021a).

For more information, see The first year of COVID-19 in Australia: direct and indirect health effects.

High blood pressure

High blood pressure – also known as hypertension – is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, as well as chronic kidney disease. When high blood pressure is controlled by medication and lifestyle measures, the risk of developing chronic conditions is reduced (AIHW 2019).

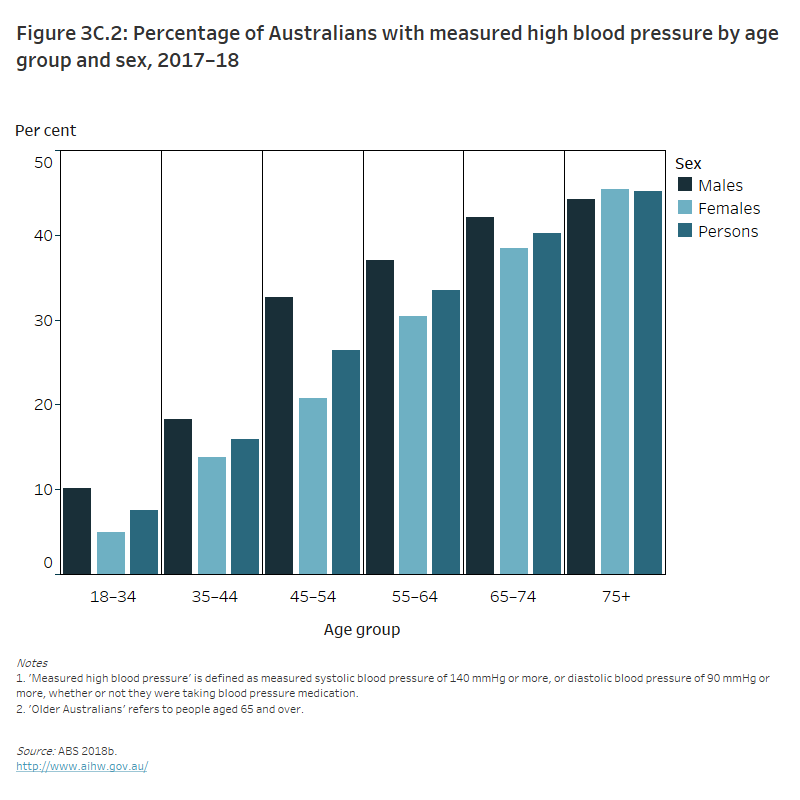

The proportion of adults with measured high blood pressure increases with age. In 2017–18, the proportion was lowest among people aged 18–44 (5.5%) and reaching 45% for those aged 75 and over (44% for men and 45% for women) (AIHW 2019) (Figure 3C.2).

Figure 3C.2: Percentage of Australians with measured high blood pressure by age group and sex, 2017–18

The column graph shows that the percentage of people with measured high blood pressure increased with age in both men and women. Between ages 18–74, the percentage of men with measured high blood pressure was higher than the percentage of women with measured high blood pressure. However, in the 75 and over age group, a higher percentage of women had measured high blood pressure than did men (45% and 44%, respectively).

High cholesterol

High cholesterol – or abnormal levels of blood lipids – is a risk factor for chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease and for some types of stroke. Blood lipids are fats in the blood and include cholesterol (a fatty substance that is an essential part of cell walls) and triglycerides (fat in the blood that assists in transporting and supplying metabolic energy throughout the body).

As with many health conditions, the prevalence of high cholesterol increases sharply with age, with a sharp increase from age 45. In 2017–18, the proportion of people with high cholesterol doubled from 6.8% for people aged 45–54 to 14% for those aged 55–64. One in 5 (21%) people aged 65 and over had high cholesterol (ABS 2018a).

Self-harm

Intentional self-harm is the act of deliberately causing physical harm to oneself. Current international coding practices for intentional self-harm are not able to distinguish between self-harm with suicidal intent and self-harm without the intent to die. Self-harm is a serious public health issue of concern to governments and communities across Australia and around the world. The number of people who intentionally self-harmed but were not hospitalised is largely unknown. Hospitalisations data for patients with intentional self-harm injuries include those with and without suicidal intent.

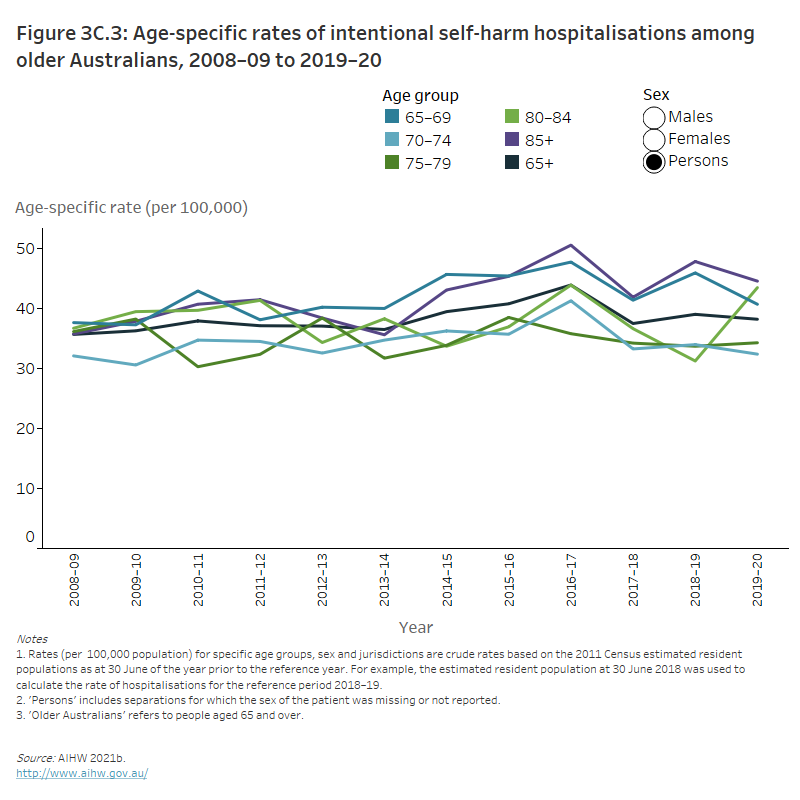

In 2019–20, the age-specific rate of intentional self-harm hospitalisation for people aged 65 years and over was 38.2 per 100,000 population. There was a peak at 44.0 in 2016–17, but it has been relatively steady since 2008–09 (AIHW 2021c). There were differences for men and women that changed with increasing age. In 2019–20, women had higher rates of intentional self-harm hospitalisations than men for ages 65–69 and ages 70–74; for ages 75–79, 80–84 and 85 and over, men had higher rates (AIHW 2021c) (Figure 3C.3).

Figure 3C.3: Age-specific rates of intentional self-harm hospitalisations among older Australians, 2008–09 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that the age-specific rates of intentional self-harm hospitalisations per 100,000 had variable differences across the time period. Men aged 85 and over had a greater age-specific rate between 2008–09 and 2019–20 compared to other age groups, with the rate peaking in 2016–17 (69.6 per 100,000).

Of deaths registered in 2019, 15% of deaths due to intentional self-harm were older Australians (aged 65 and over). This proportion was similar for men (15%) and women (16%) (ABS 2020a). See also Suicide & self-harm monitoring.

If this has raised any issues for you, these services can help:

Lifeline 13 11 14

Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467

Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800

MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78

Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636.

Crisis support services can be reached 24 hours a day.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on behaviours and risk factors among older people, see:

- ABS General Social Survey: summary results, Australia

- AIHW Alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia annual report

- AIHW Alcohol, tobacco and other drugs in Australia

- AIHW Australian Burden of Disease

- AIHW Australia’s health 2020: snapshots

- AIHW Diabetes

- Department of Health Physical activity guidelines for all Australians: for older Australians (65 years and over)

- NHMRC Australian Dietary Guidelines

Information is also available about selected health conditions and health service use among older Australians. For information on behaviours and risk factors among older Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, see Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018a. High cholesterol 2017–18 financial year. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2018b. Hypertension and measured high blood pressure, 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2018c. National Health Survey: first results, 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2020a. Causes of Death, Australia, 2019. ABS cat. no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2021. General Social Survey: summary results, Australia, 2020. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. 2009 Adult Vaccination Survey: summary results. Cat. no. PHE 135 Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2016a. Australia’s health 2016. Australia’s health series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2016b. Exploring drug treatment and homelessness in Australia: 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2014. Cat. no. CSI 23. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2019. High blood pressure. Cat. no. PHE 250. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020a. Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia. Cat. no. PHE 221. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020b. Australia’s health 2020: data insights. Cat. no. AUS 231. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020c. Australia’s health 2020: snapshots. Infectious and communicable diseases. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020d. Australia’s health 2020: snapshots. Stress and trauma. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020e. Insufficient physical activity. Cat. no. PHE 248. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020f. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Cat. no. PHE 270. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020g. Overweight and obesity. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 15 April 2021.

AIHW 2021a. Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia. Cat. no. PHE 221. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2021b. General Record of Incidence of Mortality (GRIM) books. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2021c. Suicide & self-harm monitoring. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 29 July 2021.

Department of Health 2021a. COVID-19 vaccine roll-out – 14 October. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 15 October 2021.

Department of Health 2021b. Getting your COVID-19 vaccination. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 9 May 2021. Viewed 2021.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) 2009. Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 2021.

NHMRC 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 2021.

NHMRC 2020. Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. Canberra: NHMRC. Viewed 2021.