Older Australians who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex

The LGBTI communities include individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex or otherwise diverse in gender, sex or sexuality. Each community may have its own experiences and needs, and so too will the individuals in these groups. Older LGBTI Australians have lived through many periods of social and cultural transition. While such experiences may be shared among some in this older age group, the older LGBTI population is diverse. What being part of the community means to each older person may be unique.

Data about LGBTI communities in Australia are slowly developing but are currently limited. This feature article presents the national information currently available about older same-sex couples, recognising that this is a limited picture of the experiences of LGBTI communities. Comparisons throughout this article are made to the most appropriate comparison group for which data are available.

Throughout this feature article, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus is specified. The ‘Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this feature article, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented.

There are very little data available regarding the older Australian LGBTI community. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has been collecting data on sexual orientation since 2007 when a question was included in the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Questions on sexual orientation have also been asked in the General Social Survey since 2014. The Melbourne Institute’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Australia (HILDA) longitudinal survey of Australian households included a question on sexual identity in waves 12 (2012) and 16 (2016) as part of the self-completion questionnaire (Wooden 2014). For more information, see HILDA Survey.

While sex and/or gender orientation and identity may be captured in some surveys and administrative collections, it is not necessarily the case that the data can be published due to issues of reliability and confidentiality, particularly for subgroups such as those aged 65 and over. The Census, enumerating all persons in Australia on Census night, has been able to capture and publish considerable information about partners in same-sex couples, and older partners.

Data about same-sex couples (both male and female) from the Census have been available since 1996 (ABS 2013). More recently, data have included sexual orientation and gender identity. The 2016 online Census had an opt-in question for people to more fully identify their sex or gender. This allowed the choice of ‘Other’, coupled with a response box to provide further detail. This was part of an initiative to make it possible for Australians to report their sex in a way not limited to ‘male’ or ‘female’ in the Census (ABS 2017).

The 2021 Census did not include and questions on sexual orientation or gender identity. Through testing, the ABS assessed that there was not sufficient confidence in the quality of the data that would be obtained. For sexual orientation, testing revealed a range of sensitivities, including privacy concerns, discomfort or a lack of comprehension of the question. For more information, see the ABS 2021 Census topics and data release plan.

For information about the limited availability and reporting of data about older people, see Key data gaps.

Demographic profile

In the 2016 Census, there were almost 4,800 cohabiting older partners (aged 65 and over) in same-sex couples. Nearly 3 in 5 were male partners in same-sex couples (59%, or 2,800), while 2 in 5 were female (41%, or 2,000) (ABS 2018a).

Overall, 5.3% of people in same-sex couples were aged 65 or over, compared with 20% of people in opposite-sex couples (ABS 2018a). This is higher than reported in the 2011 Census, when 3.8% of people in same-sex couples were aged 65 or over (ABS 2013). As the Census only captures information about relationships within each household, non-cohabiting couples, both same-sex and opposite-sex, are not included in Census figures.

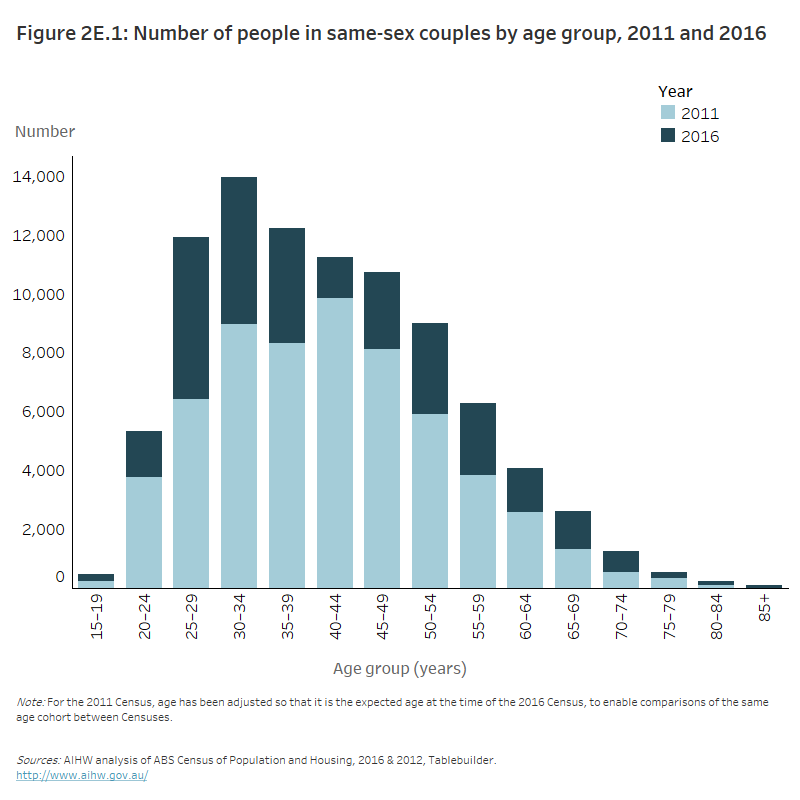

While more older people are reporting being in same-sex couples, it is to a far smaller extent than among younger age groups (Figure 2E.1). This might indicate less of a willingness by people of older ages to identify in this way (ABS 2018a).

Figure 2E.1: Number of people in same-sex couples by age group, 2011 and 2016

The overlapping column chart shows the proportion of same-sex couples by age groups in 2011 and 2016. In 2011 the greatest proportion of same-sex couples were aged 40–44 (16%), whereas in 2016 the greatest proportion of same-sex couples were aged 30–34 (16%).

Older people with diverse sex and/or gender identity

According to the 2016 Census, older people made up a smaller proportion of the 1,260 people who reported a diverse sex and/or gender identity (including intersex/indeterminate, transgender, non-binary, another gender and ‘other’ (not further defined)) compared with younger Australians. As this was a new question, introduced on an opt-in basis, it is likely the 2016 Census did not capture all sex and gender-diverse individuals.

1 in 17 (5.9%) people who reported a diverse sex and/or gender identity were older Australians (aged 65 and over). This is likely an underrepresentation due to the decreasing preference for online forms with age (ABS 2017). This question was not included in the 2021 Census.

Population surveys are another source of information about older LGBTI Australians. Estimates from the 2019 ABS General Social Survey show that 1 in 10 (10%) of those who identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual were aged 55 and over (Table 1). Note that these estimates have a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution (ABS 2020).

Population estimates suggest that a higher proportion of younger Australians identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or another sexual minority orientation (for example, queer, pansexual) than older Australians (Wilson et al. 2020). In parallel with older Australians’ lower reported rates of being in a same-sex couple, these data might reflect changing societal attitudes and younger people’s greater willingness to report their sexual orientation.

|

Age group |

Heterosexual |

Gay, Lesbian or Bisexual |

Total persons |

|---|---|---|---|

|

<55 |

12,306.5 |

481.1* |

13,354.2 |

|

55–69 |

3,899.3 |

44.8* |

4,081.5 |

|

70+ |

2,543.2 |

9.0** |

2,602.0 |

|

Total |

18,737.7 |

539.2 |

20,010.8 |

* Estimates have a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

** Estimates have a relative standard error greater than 50% and are considered too unreliable for general use.

Notes:

- Estimates have a high margin of error and should be used with caution.

- Cells in this table have been randomly adjusted to avoid the release of confidential data. As a result cells do not add to the totals.

Source: ABS 2020.

A new way to collect information

Recently, the ABS developed the Standard for Sex, Gender, Variations of Sex Characteristics and Sexual Orientation Variables, 2020. This standard forms part of the demographic set of items for use in surveys and administrative collections. It standardises the collection and dissemination of data relating to sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation (ABS 2021).

The 2020 standard is intended to improve the comparability and quality of data collected in Australia. It can be used by not only government but also academic and private-sector organisations in their own statistical collections. This standard will be applied to future ABS social surveys.

For more information, see the ABS Standard for Sex, Gender, Variations of Sex Characteristics and Sexual Orientation Variables, 2020.

Health

Evidence from small-scale LGBTI targeted studies, and some larger population-based surveys, indicate that, overall, LGBTI people face disparities in terms of their mental health (ABS 2008), sexual health (Kirby Institute 2018) and rates of substance use (AIHW 2018). The lack of data sources with information about people in LGBTI communities limits reporting on their health. Some information about health-based need for assistance by older people is collected in the Census.

Older people may need assistance with one of the core activity areas of self-care, communication or mobility because of a disability, long-term health condition or the effects of old age. According to the 2016 Census, 7.1% of older partners in same-sex couples aged 65–74 reported having a need for assistance with core activities, increasing to 22% among partners in same-sex couples aged 75 and over. This was similar for older partners in opposite-sex couples: 8.7% of those aged 65–74 reported having a need for assistance with core activities, increasing to 25% for those aged 75 and over (AIHW analysis of ABS 2016).

Drug use

The AIHW’s National Drug Strategy Household Survey is the only national data source that specifically collects information by sexual identity. However, it does not include estimates for people identifying as transgender, intersex or queer. In 2019, 2 in 5 (40%) people who identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual had used an illicit drug in the last 12 months, and almost 2 in 5 (38%) had exceeded the lifetime risk guidelines for use of alcohol (AIHW 2020). This information is not separately available for older people identifying as gay, lesbian or bisexual.

Aged care

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety recognised that LGBTI people, and others from diverse backgrounds, may have varied life experiences and face challenges accessing aged care services that meet their particular needs. It heard about the important role LGBTI volunteers play in helping reduce LGBTI residents’ isolation and maintaining connection to their LGBTI identity and communities (RCACQS 2021).

To help ensure aged care services are appropriate to the needs of all clients, the Aged Care Act 1997 designates some groups of people as ‘people with special needs’. Australians who identify as LGBTI are one such group. Other groups designated as ‘people with special needs’ in the Aged Care Act include people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, veterans, people who live in rural or remote areas, and older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

There is currently no way to identify LGBTI older Australians accessing aged care services. For those older people starting their journey into aged care, some information may be collected as part of the screening and assessment process.

Social support

Social support can be formal or informal and includes emotional, personal and domestic support to individuals or groups. Informal social support is commonly provided by people close to the individual, such as friends, family and community. Formal social support refers to government and non-government services and programs. This section focuses on informal social support.

Older LGBTI people may receive social support from others, but also provide it in the form of volunteering or caring. According to the 2016 Census results, 7.7% of older partners in same-sex couples reported providing unpaid child care (to their own and/or other children) compared with 17% of older partners in opposite-sex couples. Just under 700 older partners in same-sex couples provided unpaid assistance to a person with disability (14%), similar to the proportion of older partners in opposite-sex couples (16%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2016).

Housing and living arrangements

In 2016, most older partners in same-sex couples owned their house outright (70%, 3,300 people), with a further 17% (820 people) owning with a mortgage. Renting was less common (10%) (Table 2). In comparison, older partners in opposite-sex couples were more likely to own their house outright (76%), less likely to own their house with a mortgage (11%) and less likely to be renting (8%).

|

|

Older same-sex couples (%) |

Older opposite-sex couples (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

65–69 |

70–74 |

75+ |

Total |

65–69 |

70–74 |

75+ |

Total |

|

Owned outright |

66.3 |

74.4 |

73.5 |

69.5 |

71.7 |

78.0 |

78.5 |

75.8 |

|

Owned with mortgage |

22.1 |

13.4 |

7.6 |

17.2 |

17.1 |

10.3 |

5.9 |

11.4 |

|

Rented |

8.7 |

9.0 |

13.0 |

9.6 |

8.4 |

7.7 |

7.7 |

7.9 |

|

Other |

1.3 |

1.3 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

4.1 |

2.5 |

|

Not stated |

1.6 |

1.9 |

4.2 |

2.0 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

3.8 |

2.4 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Notes:

- 'Older partners' refers to people aged 65 and over.

- 'Other' includes being occupied rent-free, being occupied under a life tenure scheme, being purchased under a shared equity scheme and other tenure type.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2016.

A higher proportion of same-sex couples reported living in a separate house (69%), compared with townhouses (16%) and flats or apartments (14%) (Table 2E.3).

|

Type of dwelling |

65–69 |

70–74 |

75+ |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Separate house |

69.3 |

69.0 |

71.6 |

69.0 |

|

Semi-detached, row or terrace house, townhouse |

16.4 |

14.3 |

15.3 |

15.8 |

|

Flat or apartment |

13.6 |

15.3 |

13.1 |

14.2 |

|

Other |

0.8 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

0.9 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Notes:

- 'Older partners' refers to people aged 65 and over.

- 'Other' includes ‘not stated’.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2016.

Older LGBTI people may be more vulnerable to homelessness than the rest of the population. This may be due to discrimination and individual vulnerabilities because of family rejection, trauma and mental health problems (McNair and Andrews 2020). The risk of homelessness for some may be exacerbated by a lack of support from family (McNair and Andrews 2020). There is currently no available national information about this.

Employment and work

People in same-sex couples, overall, tend to be more highly educated and have higher labour force participation rates than people in opposite-sex couples (ABS 2018).

In 2016, around 1 in 4 older partners in same-sex couples (27%, 1,300 people) were in the labour force; that is, either employed or unemployed.

Of all older partners in same-sex couples (aged 65 and over):

- 73% were not in the labour force

- 26% were employed

- 0.9% were unemployed.

In comparison, 83% of partners in opposite-sex couples were not in the labour force, 17% were employed and 0.4% were unemployed (ABS 2018).

Over one-third (35%) of partners in same-sex couples aged 65–69 were in the labour force, and this declined with age (20% of those aged 70–74 and 12% of those 75 and over) (ABS 2018).

Income and finances

In 2016, older people in same-sex couples were more likely to earn higher incomes than people in opposite-sex couples, with 7.8% earning $2,000 or more per week compared with 3.6%, respectively. The majority of older partners in same-sex couples (89%) reported incomes of less than $2,000 per week which is similar to, but somewhat lower than, opposite-sex couples (92%) (Table 2E.4).

|

|

Partners in same-sex couples |

Partners in opposite-sex couples |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Less than $2,000 per week |

$2,000 or more per week |

Total |

Less than $2,000 per week |

$2,000 or more per week |

Total |

|

Age group (years) |

Number |

|||||

|

65–69 |

2,344 |

248 |

2,631 |

665,115 |

36,646 |

722,477 |

|

70–74 |

1,132 |

75 |

1,252 |

483,269 |

17,120 |

520,334 |

|

75–79 |

479 |

32 |

537 |

322,598 |

8,526 |

348,972 |

|

80+ |

295 |

18 |

349 |

284,889 |

7,237 |

315,275 |

|

Total |

4,250 |

373 |

4,769 |

1,755,871 |

69,529 |

1,907,058 |

|

|

% |

|||||

|

65–69 |

89.1 |

9.4 |

100.0 |

92.1 |

5.1 |

100.0 |

|

70–74 |

90.4 |

6.0 |

100.0 |

92.9 |

3.3 |

100.0 |

|

75–79 |

89.2 |

6.0 |

100.0 |

92.4 |

2.4 |

100.0 |

|

80+ |

84.5 |

5.2 |

100.0 |

90.4 |

2.3 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

89.1 |

7.8 |

100.0 |

92.1 |

3.6 |

100.0 |

Notes:

- 'Older couples' refers to people aged 65 and over.

- Total includes Income not stated.

- This table is based on place of enumeration.

Source: ABS 2018.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on older Australians who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex see:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2008. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2007: summary of results. ABS cat. no. 4326.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2013. Australian social trends – same-sex couples. ABS cat. no. 4102.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2016. Microdata: Census of Population and Housing, 2016. ABS cat. no. 2037.0.30.001. AIHW analysis using TableBuilder. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2017. Census of Population and Housing: reflecting Australia - stories from the Census, 2016. Sex and gender diversity in the 2016 Census. ABS cat. no. 2071.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2018. Census of Population and Housing: reflecting Australia – stories from the Census, 2016. Same-sex couples. ABS cat. no. 2071.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2020. General Social Survey: summary results, Australia. ABS cat. no. 4159.0. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

ABS 2021. Standard for Sex, Gender, Variations of Sex Characteristics and Sexual Orientation Variables. ABS cat. no. 1200.0.55.012. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 2021.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2018. Australia’s health 2018. Cat. no. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Cat. no. PHE 270. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

Kirby Institute 2018. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infection in Australia: annual surveillance report 2018. Sydney: Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales. Viewed 2021.

McNair R and Andrews C 2020. Federal Parliamentary Inquiry into Homelessness 2020. Pride Foundation Australia submission. Submission 53. Viewed 20 September 2021.

RCACQS (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety) 2021. Final report: care, dignity and respect. Canberra: RCACQS. Viewed 2021.

Wilson T, Temple J, Lyons A and Shalley F 2020. What is the size of Australia’s sexual minority population? BMC Research Notes 13:535. Viewed 2021.

Wooden M 2014. The measurement of sexual identity in wave 12 of the HILDA Survey (and associations with mental health and earnings). HILDA Project discussion paper series, no. 1/14. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Viewed 2021.