Justice and safety

Older Australians can face ageism, discrimination, abuse and other forms of violence, and they may have encounters with the justice system - as either a victim or perpetrator. As for all Australians, older people may be concerned about their safety. For example, age-related factors such as increasing frailty, cognitive impairment or dependence on others can make some older people more vulnerable to abuse (ALRC 2017).

This page presents information relating to issues around justice and safety. Throughout this page, ‘older people’ refers to people aged 65 and over. Where this definition does not apply, the age group in focus is specified. The ‘Older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’ feature article defines older people as aged 50 and over. This definition does not apply to this page, with Indigenous Australians aged 50–64 not included in the information presented.

For more information on the health status and social support of older Australians see Health—status and functioning and Social support.

Discrimination against older people

Discrimination can make participating in activities difficult for people, including older Australians (aged 65 and over). Age discrimination refers to treating a person less favourably, or not giving them the same opportunities as others, due to judgements about their age (AHRC 2014). It can restrict older people’s participation and inclusion in all aspects of life. Perceptions of older people being less deserving, incapacitated or in need of protection, can affect the ways in which services are accessed and delivered, particularly in the workplace, healthcare and aged care, and within families and local communities (Benevolent Society 2017; COTA 2021).

Age discrimination in the workplace

In Australian workplaces, age discrimination can be an ongoing barrier and occurrence for some older people. In 2015, the first National Prevalence Survey of age discrimination in the workplace was conducted across Australia. More than 1 in 4 (27%) Australians aged 50 and over reported experiencing some form of age discrimination in the workplace in the last 2 years (AHRC 2015).

Based on the survey data in 2015:

- 1 in 5 (20%) older Australians (aged 65 and over) experienced age discrimination on at least one occasion in the workplace in the last 2 years

- Australians aged 55–64 were more likely to experience age discrimination, with around 1 in 3 people aged 55–59 (32%) and 3 in 10 people aged 60–64 (31%)

- Men and women experienced age discrimination at similar rates in the last 2 years (28% and 26%, respectively) (AHRC 2015).

However, as people get older, they are less likely to remain employed to experience discrimination in the workplace. For more information on older Australians and retirement, see Employment and work.

Abuse of older people

Elder abuse is commonly defined as the ‘single, or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person’ (WHO 2020). Within this definition, elder abuse can take various forms, including physical, psychological, financial and sexual abuse, as well as neglect.

The risk factors associated with elder abuse include, but are not limited to:

- isolation

- functional dependency and disability

- poor physical and mental health

- changes in living arrangements

- financial pressures on or from children

- mistreatment by adult children

- ageist attitudes within the community (Joosten et al. 2017; WHO 2020).

The mistreatment and abuse of older Australians can occur in both formal and informal relationships, and it can involve close, loved and trusted family members. Currently the prevalence of elder abuse in Australia is not known. Neither is the type of abuse, the perpetrator or in what context the abuse may be more likely to occur (AIHW 2019a).

Worldwide, an estimated 1 in 6 (16%) people aged 60 and over have experienced elder abuse in the past year (WHO 2020). In 2016, the estimated prevalence of older Australians experiencing elder abuse was likely to be between 2% and 14% in any given year, with neglect possibly occurring at higher rates (Kaspiew et al.2016).

Across Australia in 2017–18, more than 10,900 calls were made to elder abuse helplines, where emotional and financial abuse were the most common types reported (AIHW 2019b).

Financial abuse

Financial abuse can be defined as the misuse or theft of a person’s assets or money. This can include behaviours such as using a person’s finances without their permission, power of attorney privileges outside their intended purposes, withholding care for financial gain, or selling and transferring property against a person’s wishes (CAG 2020).

Most older Australians (aged 65 and over) wish to remain independent and active within the community. However, there are those who experience the challenges of ageing and require support and assistance from families and professional service providers. In some instances, older Australians who have a dependence on someone’s care, may require a power of attorney to act and make decisions on their behalf. Unfortunately, there is a potential for the appointed person or organisation to misuse this power (AIFS 2020).

Financial abuse is a form of elder abuse that is most likely committed by a family member, a trusted friend and/or caregiver. Analysis of data from Seniors Rights Victoria showed that the majority (92%) of abuse was committed by a family member and most often (67%) by an adult child (AIHW 2019a; Joosten et al. 2015). There is currently no national data available on the prevalence of financial abuse (AIFS 2020; CAG 2020).

Older Australians as targets for scammers

Scams seek to obtain money or other goods from vulnerable and unsuspecting individuals through dishonest means.

In June 2019, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) reported that almost 1 in 5 Australians experienced a scam in the past 5 years, with 1 in 4 being affected more than once. However, while people aged 65 and over made the most reports to Scamwatch (25,100) in 2019, the age group that reported the highest financial loss was those aged 55–64 (nearly $30 million). This age group may have the highest financial loss due to the accumulated wealth at these ages, along with interest in investment opportunities (ACCC 2020).

Older Australians can also experience door-to-door, home maintenance, and telemarketing scams. However, the most common scams reported by the ACCC for people aged 65 and over related to investments, dating and romance, and remote access. In 2019, scam phone calls claiming to be from NBN Co. for remote access affected people aged 65 and over more than any other age group. It was estimated that these scams alone cost older Australians more than $2.5 million (ACCC 2020).

Sexual assault

According to the ABS 2016 Personal Safety Survey, sexual assault is defined as any act of a sexual nature carried out against a person’s will using physical force, intimidation or coercion. Sexual assault can also involve a broad range of behaviours including sexual harassment and sexualised bullying (ABS 2017; Tarczon and Quadara 2012).

According to the ABS 2016 Personal Safety Survey, acts of sexual harassment include:

- indecent phone calls, text, emails or posts (internet social networking sites or mail)

- indecent exposure

- inappropriate comments

- unwanted touching, grabbing and kissing or fondling

- distribution or posting of pictures or videos without consent, that are sexual in nature

- exposure to pictures, videos, or materials that are sexual in nature (ABS 2017; AIHW 2019b).

In 2016, an estimated 4.7% of older women (aged 65 and over) and 3.7% of older men (aged 65 and over) had experienced sexual harassment in the last 12 months, and 0.3% of both older women and men experienced sexual assault in the last 12 months (ABS 2017).

Substandard care in residential aged care services

Substandard care and abuse are problems that affect some people living in residential aged care services. Substandard care can occur in both routine and complex areas of care for residents. It can involve deliberate acts of harm and forms of abuse - including physical and sexual violence. This can include restrictive practices, such as restraining people to their bed or administering medication with the intent to manage people’s behaviour (RCACQS 2021).

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety found that many older Australians living in residential aged care services experienced substandard care and abuse (including neglect). Estimates reported indicate that:

- In 2019–20, around 5,700 allegations of assault were made through mandatory reporting under the Aged Care Act 1997. A further 27,000 to 39,000 alleged assaults were reported that were exempt from mandatory reporting, as they were resident-on-resident incidents.

- Across Australia, residential aged care services made around 24,700 reports of intent to restrain and 62,800 reports of physical restraint devices, in the last quarter of 2019–20 (RCACQS 2021).

At 30 June 2019, just over half (53%) of the people living in permanent residential aged care had a diagnosis of dementia. People with dementia can be particularly vulnerable to abuse, and this can be increased in residential aged care settings (AIHW 2019a, AIHW 2020a). Elder abuse incidents can go undetected, especially where an older person is not in a position to report the abuse (AIHW 2019a).

The effects of COVID-19 on the safety of older Australians

Individuals at greater risk of developing a severe illness, being hospitalised or dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are older people and those with underlying comorbidities. To August 2020, the highest number of COVID-19 deaths occurred among those aged 80–89 (294) (ABS 2020a). The greater health impact on older people was reported as contributing to negative attitudes and stereotypes about the health and functioning of older Australians (Holt et al. 2020).

During the pandemic, the protections put around older people may have also put them at risk of harm. The social restrictions may have resulted in social disconnection and isolation among older Australians. This may have affected their overall safety and health (Holt et al. 2020; Patterson 2020).

Although health policies aimed to reduce the transmission of COVID-19 to vulnerable populations in aged care facilities, social isolation and visitor restrictions may have contributed to declines in the health and wellbeing of residents. The potential harms caused include reduced mobility, pressure injuries, loneliness, anxiety, depression and feelings of fear and boredom (ACQSC 2021).

For more information on the effects of isolation and social support for older Australians, see Social support.

Older prisoners

A prisoner is commonly considered ‘older’ around the age of 45, this being 10 to 20 years younger than an older person in the community. Their social and lifestyle characteristics, before and during incarceration, means prisoners experience early onset of age-related conditions. This is referred to as accelerated ageing (AIHW 2020b).

At 30 June 2020, older prisoners (aged 45 and over) represented just over 1 in 5 (22%) of the Australian prisoner population. The population aged 65 and over made up 1 in 8 (13%) of the older prisoner population and 3% of overall Australian prisoners (ABS 2020b).

Over the long term, the population of older prisoners in Australia has grown more than the population of younger prisoners. Between 2010 and 2020, the number of older prisoners (aged 45 and over) in Australia grew from around 5,600 to 9,300 - a growth of 68%. Conversely, the overall older prisoner population decreased by 2.9% between 30 June 2019 and 30 June 2020 (AIHW 2020b; ABS 2020b).

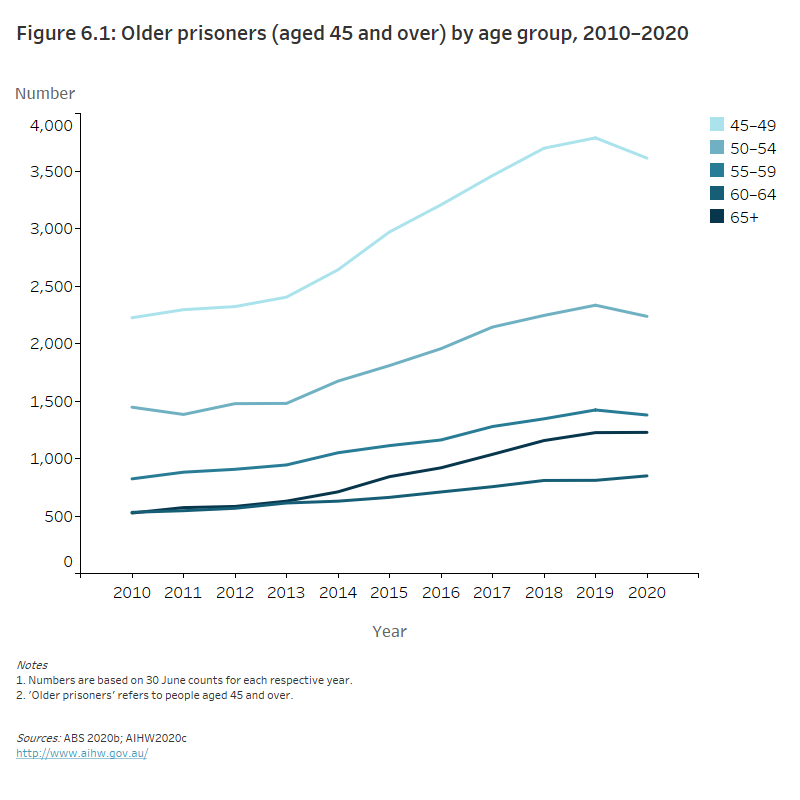

Prisoners aged 65 and over increased the most over the 2010-2020 period, from 530 to 1,200 prisoners, up 133%. Between 30 June 2019 and 30 June 2020 the population aged 60–64 showed the greatest increase at 4.8%, from 810 to 850 prisoners (ABS 2020b; AIHW 2020c) (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1: Older prisoners by age group, 2010–2020

The line graph shows that the number of older prisoners has increased across the decade from 2010–2020. The greatest increase in prisoners was in Australians aged 45–49 (2,224 prisoners in 2010 compared to 3,612 in 2020). Between 2019 and 2020 the number of prisoners aged 45–59 decreased by between 3.1% and 4.6%.

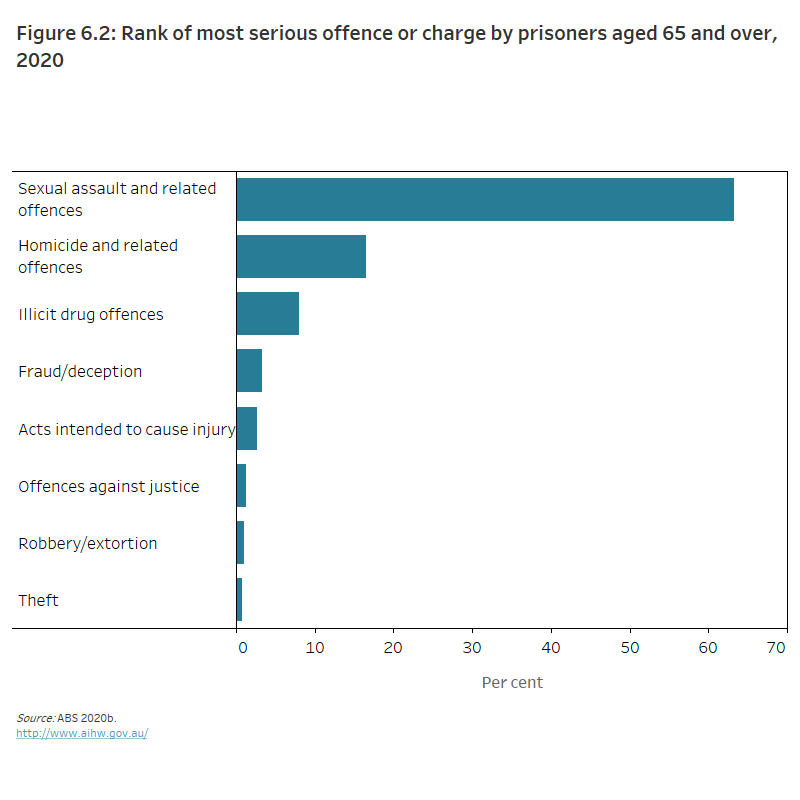

The Australian prisoner population was predominantly male (92%) in 2020, and 3.2% of all male prisoners were aged 65 and over. Australia’s population is ageing both in prison and in the community generally because people are living longer. In 2020, nearly 2 in 3 (63%) prisoners aged 65 and over had a most serious offence or charge of sexual assault and related offences, while 1 in 6 (17%) had a most serious offence or charge of homicide and related offences. (ABS 2020b) (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2: Rank of most serious offence or charge by prisoners aged 65 and over, 2020

The bar graph shows that in 2020 the largest proportion of serious offences or charges for older Australians was for sexual assault and related offences (63%). Other common offences were for homicide and related offences (17%) and illicit drug offences (8%).

For more information on older Australian prisoners, see Health and ageing of Australia’s prisoners 2018.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on the justice and safety of older Australians, see:

- AIHW Elder abuse: context, concepts and challenges

- Attorney-General’s Department National Plan to Respond to the Abuse of Older Australians (Elder Abuse) 2019–2023

- Compass Guiding action on elder abuse

- RCACQS Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety

- Scamwatch Advice for older Australians

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2017. Personal Safety, Australia 2016. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 29 March 2021.

ABS 2020a. COVID-19 Mortality. Canberra: ABS. Viewed 18 March 2021.

ABS 2020b. Prisoners in Australia data cubes. Prisoner characteristics, Australia (Tables 1-13). Canberra: ABS. Viewed 18 March 2021.

ACCC (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission) 2020. Targeting scams 2019: a review of scam activity since 2009. Canberra: ACCC. Viewed 2021.

ACQSC (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission) 2021. Supporting safe, quality care for aged care consumers during visitor restrictions. Canberra: ACQSC.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) 2014. Age discrimination. Sydney: AHRC. Viewed 8 April 2021.

AHRC 2015. National Prevalence survey of age discrimination in the workplace. Sydney: AHRC. Viewed 16 March 2021.

AIFS (Australian Institute of Family Studies) 2020. Powers of attorney and financial abuse of older people in Australia. Melbourne: AIFS. Viewed 29 March 2021.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019a. Australia’s welfare 2019 data insights. Chapter 7 Elder abuse: context, concepts and challenges. Australia’s welfare series no. 14. Cat. No. AUS 226. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2019b. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019—In brief. Cat. no. FDV 4. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020a. Dementia. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 30 March 2021.

AIHW 2020b. Health and ageing of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Cat. no. PHE 269. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

AIHW 2020c. Health and ageing of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Data tables: Health and ageing of Australia’s prisoners, 2018 supplementary tables. Table A2. Cat. no. PHE 269. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 2021.

ALRC (Australian Law Reform Commission) 2017. Elder abuse—A national legal response: Final report. Sydney: ALRC. Viewed 18 March 2021.

Benevolent Society 2017. The drivers of ageism: summary report. Sydney: Benevolent Society. Viewed 16 March 2021.

CAG (Council of Attorneys-General) 2020. National Plan to Respond to the Abuse of Older Australians (Elder Abuse) 2019-2023. Canberra. Attorney General's Department. Viewed 2021.

COTA (Council on the Ageing) 2021. Ageism and discrimination. Canberra: COTA Australia. Viewed 16 March 2021.

Holt NR, Neumann JT, McNeil JJ and Cheng AC 2020. Implications of COVID-19 in an ageing population. Medical Journal of Australia 213(8):342–344.e1. Viewed 2021.

Joosten M, Dow B and Blakey J 2015. Profile of elder abuse in Victoria: analysis of data about people seeking help from Seniors Rights Victoria—summary report, June 2015. Melbourne: National Ageing Research Institute and Senior Rights Victoria. Viewed 30 March 2021.

Joosten M, Dow B and Vrantsidis F 2017. Understanding elder abuse: a scoping study. Melbourne: National Ageing Research Institute. Viewed 29 March 2021.

Kaspiew R, Carson R and Rhoades H 2016. Elder abuse: understanding issues, frameworks and responses. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 16 March 2021.

Patterson K 2020. Ageism and the effects of COVID-19 on older Australians. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne. Viewed 2021.

RCACQS (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety) 2021. Final report: care, dignity and respect. Volume 1: summary and recommendations. Canberra: RCACQS. Viewed 2021.

Tarczon C and Quadara A 2012. The nature and extent of sexual assault and abuse in Australia (ACSSA Resource Sheets). Melbourne: Australian Centre for the Study of Sexual Assault, Australian Institute of Family Studies. Viewed 2021.

WHO (World Health Organization) 2020. Elder abuse. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 30 March 2021.