Early childhood and transition to school

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Early childhood and transition to school, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Early childhood and transition to school. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/childcare-and-early-childhood-education

MLA

Early childhood and transition to school. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/childcare-and-early-childhood-education

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Early childhood and transition to school [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 26]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/childcare-and-early-childhood-education

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Early childhood and transition to school, viewed 26 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/childcare-and-early-childhood-education

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

On this page

The early childhood years are a time when children begin to learn to communicate and get along with others, as well as adapt their behaviour, emotions, and attention (CDCHU 2011). These developmental skills play an important role when a child transitions to primary school and establish the foundations for academic and life success (Pascoe and Brennan 2017).

Early childhood education and care programs assist parents with their caring responsibilities. These programs can support the economic and social participation of parents, while helping to ease the transition to full-time school for children (Warren et al. 2016).

How many children are in child care?

In Australia, early childhood education and care services are provided by government and non-government organisations. They may be formal or informal.

Formal and informal care

Child care can be categorised as formal or informal.

Formal care: The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) defines formal child care as regulated care away from the child’s home, including:

- outside school hours care

- centre-based day care

- family day care (ABS 2017).

Preschool was once considered a type of formal care, however since 2005 the definition of formal care has excluded preschool. Preschool data is collected separately from child care data and is discussed later on this page.

Informal care: The ABS defines informal care as non-regulated care, paid or unpaid. Informal care may be provided by:

- grandparents

- other relatives (including siblings and a parent living elsewhere)

- other people (including friends, babysitters, and nannies)

- other child minding services (for example, a crèche) (ABS 2017).

Child Care Subsidy approved child care

The Australian Government provides a Child Care Subsidy to support children and families attending early childhood education and care services. In the March quarter 2022, 48% of 0–5-year-olds (883,510 children) and 33% of 0–12-year-olds (1,334,240 children) used Australian Government subsidised child care (Figure 1). Of all children attending child care, 62% attended Centre Based Day Care, 37% attended Outside School Hours Care, and 6.4% attended Family Day Care. The average weekly hours of child care use per child was 27 hours (DoE 2023).

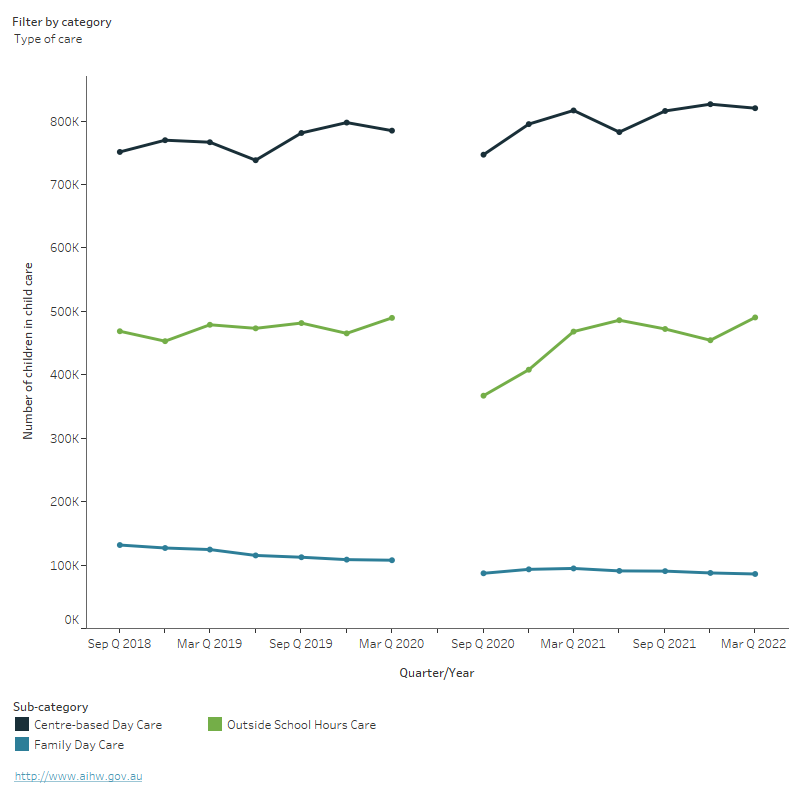

Figure 1: Number of children using Australian government subsidised child care, September quarter 2018 to March quarter 2022

Number of children using Australian government subsidised child care, March quarter 2019 to March quarter 2022

The line graph shows a steep decline in the number of children who access Australian government subsidised child care in the September 2020 quarter compared to prior to March 2020, likely a result of COVID-19. The decline was greatest for Outside School Hours Care, followed by Centre-based Day Care. Of all states and territories, Victoria had the largest decline. The number of children attending Australian government subsidised child care had returned to pre-March 2020 levels by the March 2021 quarter, except in Victoria where attendance remained lower until mid-2021. No data is available for the June 2020 quarter.

Notes

1. Only includes children who accessed Australian government subsidised child care who had been allocated a Customer Reference Number by Centrelink.

2. Figures and tables measuring total children includes children in in-home care. For confidentiality, when total children are reported for jurisdictions, children in in-home care are not included.

3. The introduction of a new child care package in July 2018 changed major components of the child care system resulting in a break in series for some child care metrics.

4. Due to the temporary measures implemented as part of the Australian Government’s Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) COVID-19 relief package, data for June quarter 2020 are not available.

5. Children accessing government supported child care through special purposed grants delivered through the Child Care Community Fund are not included.

6. Quarters can be of different lengths, for example, only 11 weeks of data were available for September quarter 2020, while September quarter 2021 contained 14 weeks of data.

Source: DoE 2023.

Participation in preschool programs aim to meet the learning needs of children through play-based activities (DET 2018). These programs are generally provided by preschools or centre-based day care services (formerly long day care) (see glossary) in the years before children enter full-time school (Warren et al. 2016). Preschool participation is not compulsory and age entry requirements vary across states and territories (ABS 2022b). Preschool subsidies are available in all states and territories (DoE 2022b).

Preschool and centre-based day care

A preschool program can be offered by a preschool or a centre-based day care service.

According to the ABS (2014), preschools deliver a structured educational program to children before they start school. The preschool program can be delivered from a stand-alone facility or the preschool may be integrated or co-located within a school. Preschools can be operated by government or non-government entities.

Centre-based day care services provide child care to 0–5-year-olds. Services may include delivery of a preschool program by a qualified teacher. Like preschools, centre-based day care can be offered from a stand-alone facility or be co-located within a school. Centre-based day care can also be operated by for-profit and not-for-profit organisations.

In 2022, 334,440 4–5-year-olds were enrolled in a preschool program, a decrease of 1.3% since 2021 (ABS 2023). More children were enrolled in a preschool program through a centre based day care service (49%) than a preschool (37%) (ABS 2023).

Of 4–5-year-olds enrolled in a preschool program in 2022:

- About 266,100 were aged 4 and 68,300 aged 5, representing 87% of all 4-year-olds and 22% of all 5-year-olds (note that the lower proportion of 5-year-olds is due to those children starting primary school).

- More than 17,500 4-year-olds enrolled in a preschool program were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) children and about 4,000 were First Nations children aged 5, representing 91% and 21% of all First Nations children aged 4 and 5, respectively.

- The number of First Nations children enrolled in a preschool in 2022 was around 2.7% higher than in 2021 (ABS 2023 and ABS 2022a). For more information see Education of First Nations people.

- 21% of all children enrolled in a preschool program were from an area in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic area quintile (see glossary) and 17% were from an area in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic area quintile (17% and 16% for 4-year-olds and 5-year-olds, respectively). The largest group of children (23%) resided in the second most advantaged socioeconomic area quintile. Each quintile represents 20% of the population.

- 72% were from Major cities, 26% from Inner and outer regional areas and 2% from Remote and very remote areas. These proportions changed minimally between 2021 and 2022.

- Most (over 95%) children were enrolled for 15 hours per week or more.

- About one-quarter (25%) were enrolled in a program where no fee was paid, which was down 9% from 2021. Forty four percent paid between $1and $4 per hour; around 1 in 3 (31%) paid $5 or more (ABS 2023).

Transition to school

This section presents information on the development of children in Australia by the time they reach primary school, using data from the 2021 Australian Early Development Census (AEDC).

What is the Australian Early Development Census?

The AEDC was introduced nationally in 2009 to measure the developmental vulnerability of children every 3 years. Data is provided by teachers using the Australian version of the Early Development Instrument. The census assesses children in their initial year of formal schooling. Parents/carers can opt out of the census if they do not want their child to participate (AEDC 2016). The proportion of eligible children participating in the AEDC has been above 95% in all collection cycles (AEDC 2022).

The AEDC measures early development across 5 domains:

- Physical health and wellbeing – physical independence, motor skills, energy levels, ability to physically cope with the school day.

- Social competence – self-control and self-confidence, ability to work and play well with others, respect for others, responsibility, ability to follow instructions.

- Emotional maturity – absence of anxious and fearful behaviour, ability to concentrate, ability to provide assistance to other children.

- Language and cognitive skills (school-based) – interest and ability relating to literacy, numeracy, memory.

- Communication skills and general knowledge – communication with children and adults, articulation, ability to tell a story (AEDC 2016).

The AEDC scores are grouped into 3 categories using benchmark scores calculated in 2009:

- developmentally on track (above the 2009 25th percentile)

- developmentally at risk (between the 2009 10th and 25th percentile)

- developmentally vulnerable (below the 2009 10th percentile).

How many children were developmentally vulnerable?

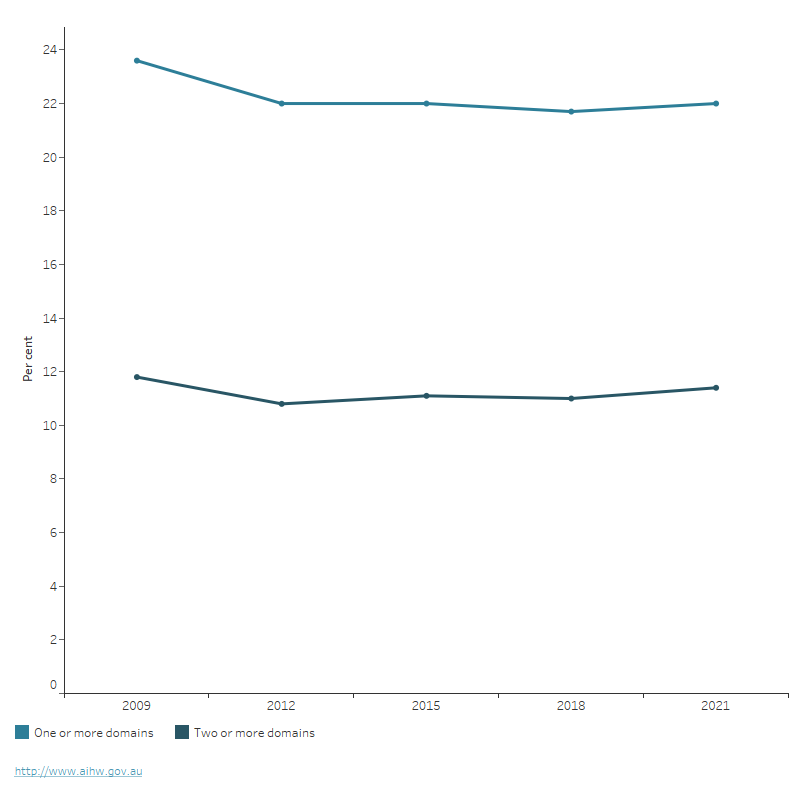

Based on the most recent data in 2021, the proportion of children in the first year of school classified as developmentally vulnerable on one or more domain(s) was 22%, while the proportion classified as developmentally vulnerable on 2 or more domains was 11%. Developmental vulnerability has remained relatively stable since 2012 and decreased slightly since 2009 (Figure 2). The percentage of children who were on track on all 5 domains decreased slightly in 2021 for the first time since 2009, dropping by 0.6 percentage points to 54.8% from its peak in 2018 of 55.4% (AEDC 2022).

Figure 2: Percentage of children in the first year of school classified as vulnerable on one or more AEDC domains(s) or on 2 or more domains, 2009 to 2021

Percentage of children in the first year of school classified as vulnerable on one or more AEDC domains(s) or on 2 or more domains, 2009 to 2021

The line graph shows a slight decline in the number of children classified as vulnerable on AEDC domains. Children classified as vulnerable on one or more domain(s) was highest in 2009 (23.6%) and lowest in 2018 (21.7%). Children classified as vulnerable on two or more domains was highest in 2009 (11.8%), decreased in 2012 (10.8%) and remained steady in 2015 (11.1%) and 2018 (11.0%), before increasing slightly in 2021 (11.4%).

Source: AEDC 2022.

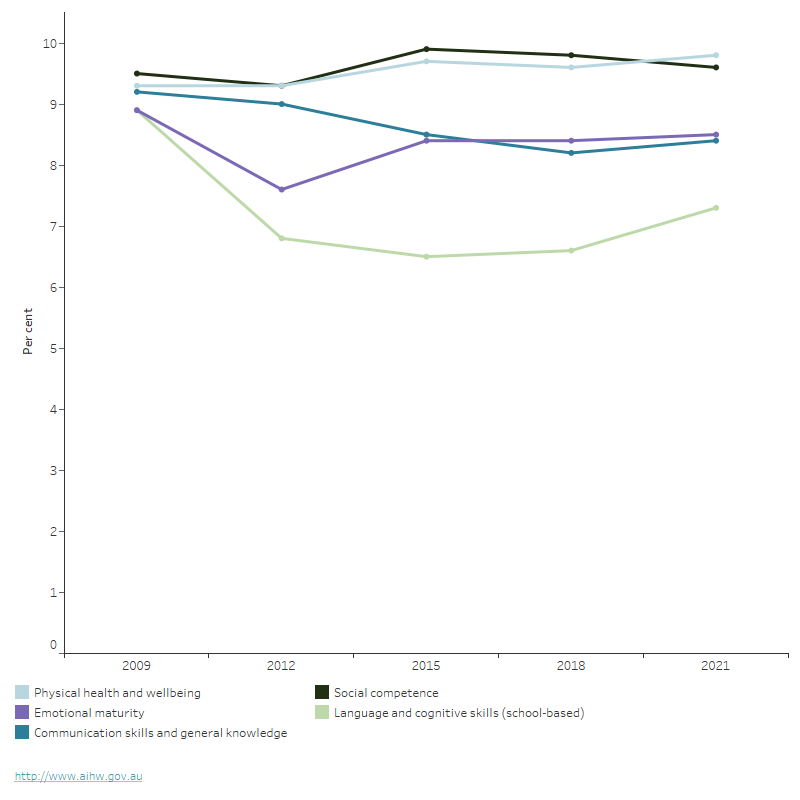

Some changes took place in the proportion of children in the first year of school considered to be developmentally vulnerable across the 5 AEDC domains between 2009 and 2021. Over this time period, the proportion of children developmentally vulnerable on:

- physical health and wellbeing increased from 9.3% to 9.8%

- social competence increased from 9.5% to 9.6%, peaking at 9.9% in 2015

- emotional maturity decreased from 8.9% to 8.5%

- language and cognitive skills decreased from 8.9% to 7.3%

- communication skills and general knowledge decreased from 9.2% to 8.4% (Figure 3).

In 2021, there were small increases in the percentage of children who were developmentally vulnerable in 3 of the 5 domains compared with 2018: language and cognitive skills (increase of 0.7 percentage points), physical health and wellbeing (0.2 percentage points) and communication and general knowledge (0.2 percentage points). The was a small decrease in the percentage of children who were developmentally vulnerable in the social competence domain (0.2 percentage point decrease), while emotional maturity remained unchanged (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportion of children in the first year of school classified as developmentally vulnerable on each of the 5 AEDC domains, 2009 to 2021

Proportion of children in the first year of school classified as developmentally vulnerable on each of the 5 AEDC domains, 2009 to 2021

The line graph shows variation in the percentage of children classified as developmentally vulnerable on the five AEDC domains. Physical health and wellbeing increased slightly (2009: 9.3%, 2012: 9.3%, 2015: 9.7%, 2018: 9.6%, 2021: 9.8%). Social competence varied but increased overall (2009: 9.5%, 2012: 9.3%, 2015: 9.9%, 2018: 9.8%, 2021: 9.6%). Emotional maturity varied on each reporting year (2009: 8.9%, 2012: 7.6%, 2015: 8.4%, 2018: 8.4%, 2021: 8.5%). Language and cognitive skills (school‑based) varied but decreased overall (2009: 8.9%, 2012: 6.8%, 2015: 6.5%, and 2018: 6.6%, 2021: 7.3%). Communication skills and general knowledge varied but decreased overall (2009: 9.2%, 2012: 9.0%, 2015: 8.5%, 2018: 8.2%, 2021: 8.4%).

Source: AEDC 2022.

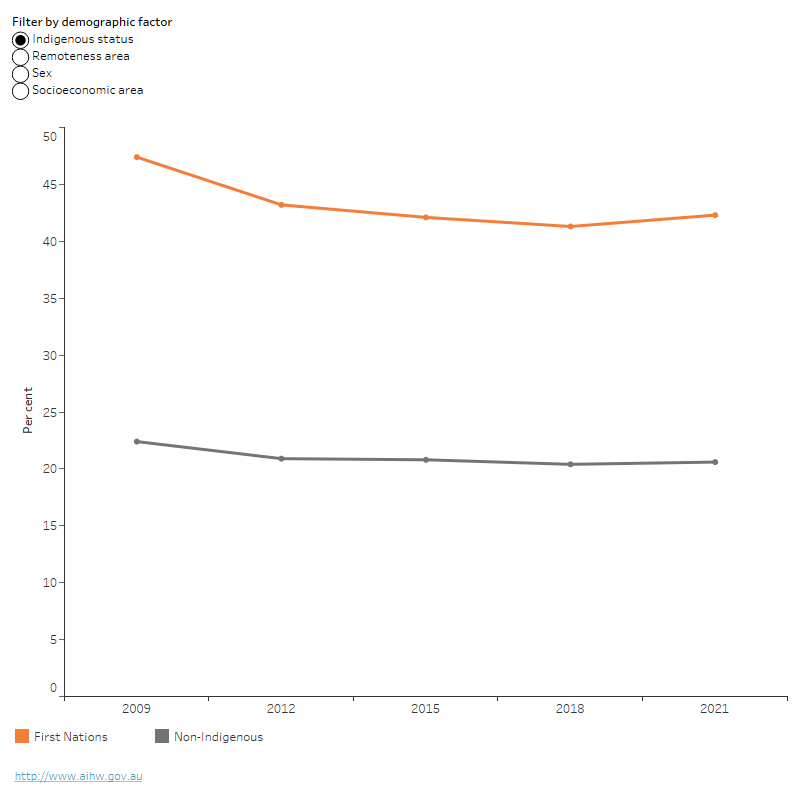

In 2021, the developmental vulnerability of children in the first year of school also differed across demographic factors:

- Boys were nearly twice as likely to be developmentally vulnerable on one or more and 2 or more domains than girls. This difference has been consistent in all AEDC collection cycles.

- 34% of First Nations children were developmentally on track across all 5 domains, a decline of 0.9 percentage points from 2018 (AEDC 2022). The proportion of First Nations children classified as developmentally vulnerable in one or more domain declined between 2009 and 2021 (see Education of First Nations people for more information).

- Children living in low socioeconomic areas (see glossary) were more likely to be developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains than children living in other socioeconomic areas. In 2021, 33% of children in the lowest socioeconomic areas were developmentally vulnerable, compared with 15% of children in the highest areas.

- Children living in Very remote areas were more likely to be developmentally vulnerable than children in other remoteness areas. In 2021, 46% of children in Very remote areas were developmentally vulnerable, compared with 21% of children living in Major cities (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Proportion of children in the first year of school classified as developmentally vulnerable on one or more AEDC domain(s) by sex, Indigenous status, socioeconomic area, and remoteness area, 2009 to 2021

The line graph shows boys a higher proportion of boys than girls were classified as developmentally vulnerable on one or more AEDC domains, the proportion of children classified as developmentally vulnerable was also higher in lower socioeconomic areas, in more remote areas, and among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than non-Indigenous people. The proportion in most groups remained reasonably steady over time.

Source: AEDC 2022.

What was the impact of COVID-19?

In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many Australian families withdrew their children from Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) services. The impacts of COVID-19 on child care attendance differed across states and territories and care types and a number of relief packages were put in place aimed at keeping ECEC services open (DoE 2022a). Locations that were subject to frequent lockdowns and school closures saw larger drops in child care use. In particular, there were substantial declines in Outside School Hours Care usage in Victoria in the September and December quarters 2020 (DoE 2022e). The number of children who attended Australian Government subsidised child care largely returned to pre-COVID-19 levels in the March quarter 2021, except in Victoria where the number of children remained below pre-COVID-19 levels until mid-2021 (Figure 1).

Research into the impact of COVID-19 on children’s development is ongoing. Initial data from the most recent AEDC found that, nationally, the impact of COVID-19 on children’s transition to school and development may have been small, with only modest increases in developmental vulnerability between 2018 and 2021 (AEDC 2022). However, the impact may have been unevenly felt, with larger increases in developmental vulnerability among First Nations children and children living in the most disadvantaged areas of Australia (AEDC 2022).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on early childhood and transition to school, see:

- Department of Education Early childhood data and reports

- ABS Preschool Education, Australia

- AEDC Australian Early Development Census.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2017) Childhood Education and Care Survey, ABS website, accessed 18 February 2019.

ABS (2022a) Preschool Education, Australia, 2021, ABS website, accessed 11 January 2023.

ABS (2022b) Preschool Education, Australia, methodology, 2021, ABS website, accessed 11 January 2023.

ABS (2023) Preschool Education, Australia, 2022, ABS website, accessed 3 May 2023.

AEDC (Australian Early Development Census) (2016) Australian Early Development Census national report 2015, AEDC, accessed 10 January 2023.

AEDC (2022) Australian Early Development Census national report 2021, AEDC, accessed 10 January 2023.

CDCHU (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University) (2011) Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of Executive Function, Harvard University, accessed 8 June 2021.

DoE (Department of Education) (2022a) COVID-19 and early childhood education and care, Department of Education website, accessed 11 January 2023.

DoE (2022b) Preschool, Department of Education website, accessed 10 January 2023.

DoE (2023) March quarter 2022 report, Department of Education website, accessed 16 March 2023.

DET (Department of Education and Training) (2018) National report: National partnership agreement on universal access to early childhood education 2016 and 2017, Department of Education and Training, Australian Government, accessed 11 January 2023.

Pascoe S and Brennan D (2017) Lifting our game: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools through early childhood interventions–December 2017, Victorian Government, accessed 8 June 2021.

Warren D, O’Connor M, Smart D and Edwards B (2016) A critical review of the early childhood literature, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, accessed 6 June 2023.