Education of First Nations people

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Education of First Nations people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Education of First Nations people. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-education-and-skills

MLA

Education of First Nations people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-education-and-skills

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Education of First Nations people [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-education-and-skills

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Education of First Nations people, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-education-and-skills

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Higher levels of education have been linked with improved health and wellbeing, health literacy, income, employment, better working conditions and a range of other social benefits (ABS 2011; Biddle and Cameron 2012; Hart et al. 2017).

Education is fundamental to improving health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people. Specific areas requiring action and improvement have been highlighted, in particular, early childhood education, school readiness and achievement, attainment of Year 12 or equivalent and tertiary and post school education (for more information, see Closing the Gap).

This page provides an overview of indicators relating to education and skills of First Nations people, progress towards the Closing the Gap education targets, and some effects of COVID-19 on the education of First Nations People. See glossary for definitions of terms used on this page.

Closing the Gap targets

In 2020, all Australian governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Coalition of peaks representatives worked in partnership to develop the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement), built around 4 Priority Reforms. The National Agreement also identifies 19 targets across 17 socioeconomic outcome areas. Five of these targets relate to school readiness and education.

National Agreement on Closing the Gap: education-related targets

Outcome area 3: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are engaged in high quality, culturally appropriate early childhood education in their early years.

- Target: By 2025, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children enrolled in Year Before Fulltime Schooling (YBFS) early childhood education to 95%.

- Status: The baseline proportion in 2016 was 77%. The most recent proportion, using data for 2021, is 96.7%. This is above the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 86.9%.

Outcome area 4: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children thrive in their early years.

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children assessed as developmentally on track in all 5 domains of the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) to 55%.

- Status: The baseline proportion in 2018 was 35%. The most recent proportion, using data for 2021, is 34.3%. This is below the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 39.8%.

Outcome area 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students achieve their full learning potential.

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (age 20–24) attaining Year 12 or equivalent (Certificate III or above) qualification to 96%.

- Status: The baseline proportion in 2016 was 63%. The most recent level, using data for 2021, is 68%. This is below the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 74.1%.

Outcome area 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students reach their full potential through further education pathways.

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 25–34 years who have completed a tertiary qualification (Certificate III and above) to 70%.

- Status: The baseline proportion in 2016 was 42%. The most recent proportion, using data for 2021, is 47%. This is below the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 51.5%.

Outcome area 7: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth are engaged in employment or education.

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth (15–24 years) who are in employment, education or training to 67%.

- Status: The baseline proportion in 2016 was 57%. The most recent proportion, using data from 2021, is 58%. This is below the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 60.5%.

Note: The baseline values for these targets were derived from the 2016 National Early Childhood Education and Care Collection (Outcome area 3), 2018 AEDC (Outcome area 4), and the 2016 Census of Population and Housing (Census) (Outcome areas 5, 6 and 7).

Prior to establishment of the National Agreement, there were 7 Closing the Gap targets set by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, 4 of which related to education. These were:

- a target to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous school attendance by 2018;

- a target to halve the gap for Indigenous children in reading, writing, and numeracy in the decade 2008 to 2018;

- a target to halve the gap for Indigenous Australians aged 20–24 with a year 12 or equivalent (Certificate II or above) qualification from 2006 to 2020;

- and a target to increase enrolment of Indigenous four-year-olds in early childhood education to at least 95% by 2025.

The Closing the Gap Report 2020 found that the first and second targets expired unmet, while the third and fourth targets which had not yet expired were on track.

Early childhood education

From 2016 to 2022 the percentage of First Nations children enrolled in early childhood education in the year before full-time schooling increased by more than 20 percentage points, from 77% to 99%. Over the same period, enrolments for non-Indigenous children decreased by 4 percentage points, from 92% to 88% (Productivity Commission 2023).

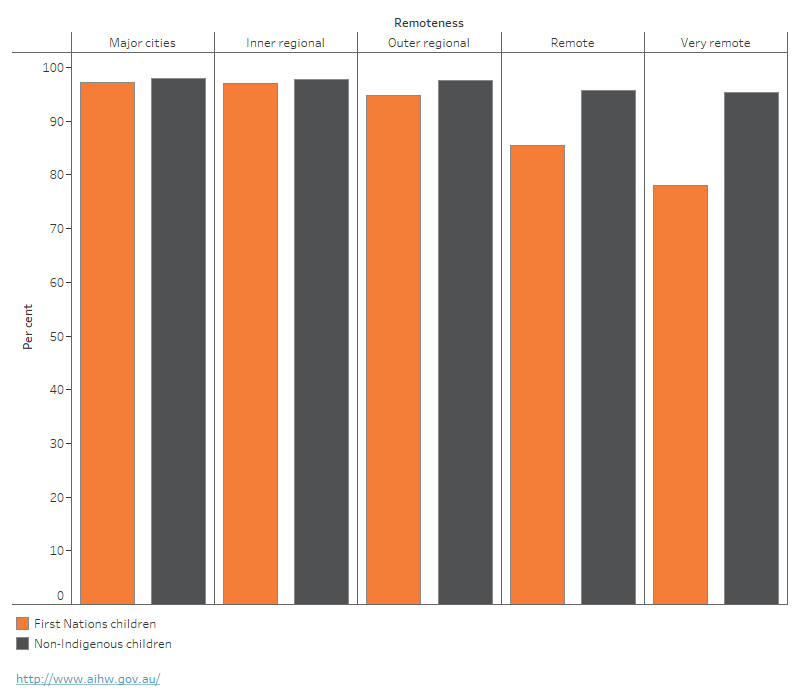

Attendance rates (the proportion of enrolled children who attended for at least 1 hour in a reference week) for First Nations children were highest in Major cities and lower in Remote and Very remote areas (Figure 1). Data by remoteness are only available for 2019.

Figure 1: Attendance rates for children enrolled in a preschool program in the year before full-time schooling, by remoteness and Indigenous status, 2019

This chart shows that the attendance rate for First Nations children enrolled in a preschool program was highest in Major cities and Inner regional areas (both 97%) and lowest in Very remote areas (78%). The attendance rate for non-Indigenous children ranged from 98% in Major cities to 95% in Very remote areas.

Note: Attendance rates are the proportion of enrolled children who attended for at least 1 hour in the reference week.

Source: SCRGSP 2020.

Early child development

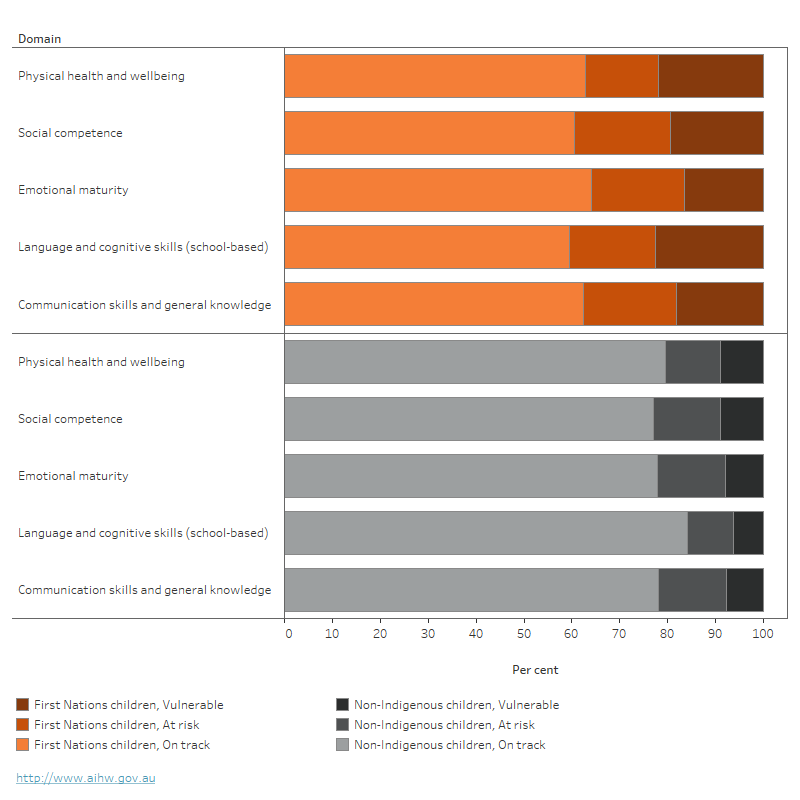

The Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) is a census type data collection for all children in their first year of full-time schooling, conducted every 3 years. Based on their observations, school teachers assess children on 5 domains of early childhood development (Figure 2).

The 2021 AEDC assessed 305,000 children, of whom 20,600 (6.8%) were First Nations. Across each of the 5 AEDC domains, around 6 in 10 (between 59% and 64%) First Nations children were assessed as being developmentally on track (Figure 2) (DESE 2022).

Around 3 in 10 (34%) First Nations children were assessed as on track on all 5 domains in 2021. While the proportion of children who were developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains was higher among First Nations children than non-Indigenous children (42% compared with 22%), the vast majority of children developmentally vulnerable on one or more domains were non-Indigenous (55,400 of 63,300).

Figure 2: Proportion of children in their first year of full-time school who were assessed as developmentally on track, at risk, or vulnerable, by Indigenous status and AEDC domain, 2021

This chart shows the proportion of children assessed as developmentally vulnerable, at risk and on track for each AEDC domain (Physical health and wellbeing, Social competence, Emotional maturity, Language and cognitive skills, and Communication skills and general knowledge). Across each of the five domains: a higher proportion of First Nations children were assessed as developmentally vulnerable (between 16%–23%) compared with non-Indigenous children (between 6%–9%); a higher proportion were assessed as at risk (15%–20% compared with 9%–14%); and a lower proportion were assessed as on track (60%–64% compared with 77%–86%).

Source: DESE 2022.

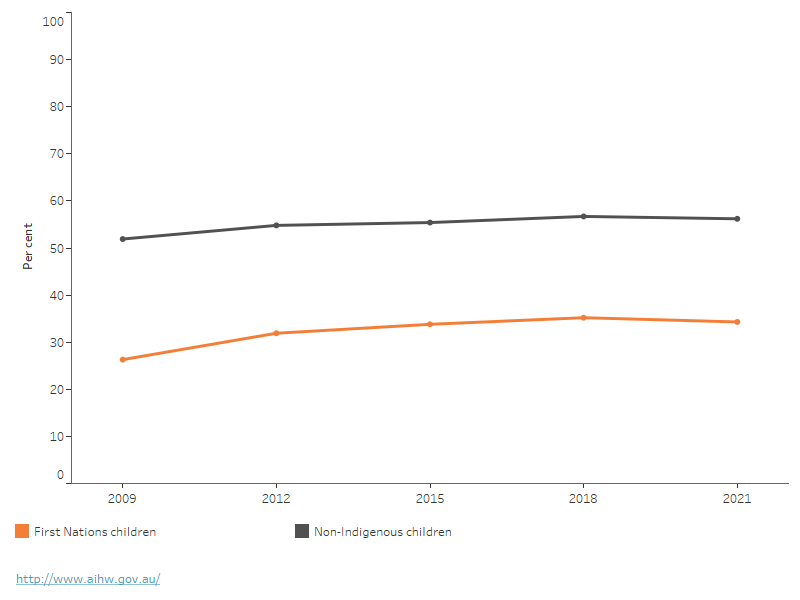

The 2021 AEDC results also showed that, nationally:

- First Nations children living in Major cities were 2.4 times as likely as those living in Very remote areas to be assessed as developmentally on track on all 5 domains (38% compared with 16%) (Figure 3).

- 64% of First Nations children were assessed as developmentally on track in the Emotional maturity domain, 63% in the Physical health and wellbeing domain, 63% in the Communication skills and general knowledge domain, 61% in the Social competence domain and 59% in the Language and cognitive skills (schools-based) domain (Figure 2).

- The gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous children assessed as developmentally on track in all 5 domains narrowed by 4 percentage points, from 26% in 2009 to 22% in 2021 (Figure 3).

- There was a slight decrease in the percentage of both First Nations and non-Indigenous children assessed as developmentally on track in all 5 domains from 2018 to 2021 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportion of children in their first year of full-time school who were assessed as developmentally on track on all 5 domains, by Indigenous status, 2009 to 2021

This chart shows that the proportion of First Nations children assessed as developmentally on track on all 5 AEDC domain(s) increased over time (from 26% in 2009 to 34% in 2021). The rate for non-Indigenous children was lower and decreased slightly over the period 2009 to 2018, from 22% to 20%.

Source: DESE 2022.

School attendance

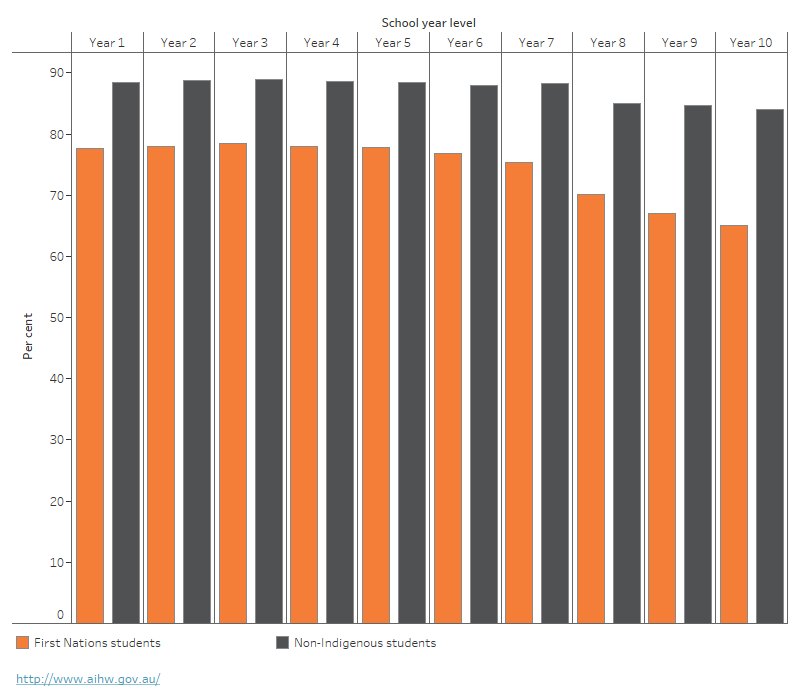

Overall, school attendance rates for First Nations and non-Indigenous students in years 1 to 10 have been relatively stable between 2014 and 2019, with a slight decreasing trend. However, between 2019 and 2022 attendance rates decreased by 7 percentage points for First Nations students (from 82% to 75%) and by 5 percentage points for non-Indigenous students (from 92% to 87%) (ACARA 2023a).

Western Australia had the largest change between 2019 and 2022, with First Nations student attendance decreasing by 9 percentage points. All jurisdictions had a decrease of 5 percentage points or greater over this period (ACARA 2023a).

In 2022, the attendance rate was 25–26 percentage points lower for First Nations students in Very remote areas (52%) than those in Inner regional areas (78%) and Major cities (77%). Attendance rates for non-Indigenous students did not vary greatly by remoteness, and the gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous students was highest in Remote and Very remote areas (ACARA 2023a).

In 2022, school attendance rates for First Nations students were steady between primary school year levels (77%–78%) but reduced as the secondary school year level increased (to a low of 65% for Year 10 students). For non-Indigenous students, the attendance rate ranged from 88%–89% during primary school and declined slightly in high school to 84% for Year 10 students (Figure 4).

Figure 4: School attendance rates, by Indigenous status and school year level, Year 1 to Year 10, 2022

This chart shows that attendance rates for First Nations students were lower than for non-Indigenous students across all primary and secondary school years. The attendance rates were steady in primary school year levels and declined during the secondary school years for both First Nations and non-Indigenous students. The gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous students widened as the secondary school year level increased.

Source: ACARA 2022 (National Student Attendance Data Collection).

Reading and numeracy

Reading and numeracy was not included as one of the 19 targets in the National Agreement on Closing the Gap but is included as an indicator for Outcome 5 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students achieve their full learning potential.

From the inception of the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) in 2008 to 2022, reading and numeracy for First Nations children have improved across most year levels, with the exception of Year 7 numeracy and Year 9 reading. Over the same period, the gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous students narrowed between 1 – 12 percentage points for all year levels that improved (ACARA 2022). Note that no NAPLAN assessment was conducted in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and disruption to student learning. From 2023 onwards there are changes to the way NAPLAN results are reported (see Changes to NAPLAN in 2023).

Changes to NAPLAN in 2023

A review of the NAPLAN standardised testing was commissioned in 2019. The review considered whether NAPLAN remains fit-for-purpose and made several recommendations for future versions of the national standardised assessment (McGaw et al 2020). Based on this review, in 2023, the test was held in Term 1 (instead of Term 2) in March. This allows results to be published earlier in the year to inform school programs and will allow teachers to better support students for the year ahead (ACARA 2022a).

In addition, from 2023 onwards, NAPLAN results will be reported against 4 levels of achievement bands, ‘Exceeding’, ‘Strong’, ‘Developing’ and ‘Needs additional support’ instead of the existing national minimum standard and 10 proficiency bands (DoE 2023). A new NAPLAN time series begins from 2023. Data reported on this page (from 2008 to 2022) cannot be compared with NAPLAN 2023 results.

The NAPLAN 2023 results show that on average, across all domains (reading, writing, spelling, grammar and punctuation and numeracy) a higher proportion of First Nations students are in the Needs additional support proficiency level than non-Indigenous students. At each year level tested (3, 5, 7 and 9), over 30% of First Nations students fall into this category compared to less than 10% of non-Indigenous students (ACARA 2023b).

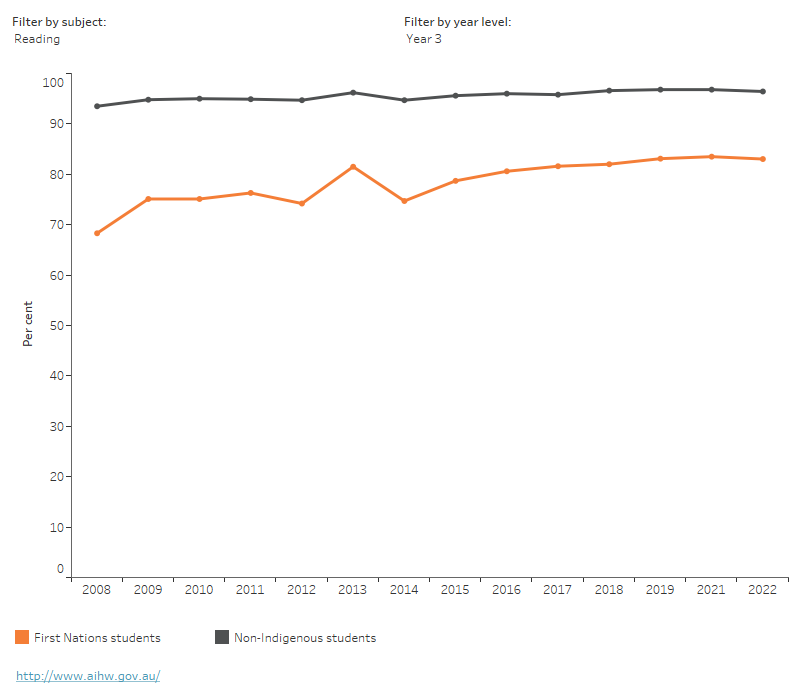

Based on NAPLAN data, between 2008 and 2022:

- the proportion of First Nations students meeting the national minimum standard for reading increased in years 3, 5 and 7, from;

- 68% to 83% for Year 3

- 63% to 79% for Year 5

- 72% to 77% for Year 7

- the proportion of First Nations students meeting the national minimum standard for numeracy increased in years 3, 5 and 9, from:

- 79% to 80% for year 3

- 69% to 78% for Year 5

- 73% to 81% for Year 9

- the gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous students at or above the national minimum standard narrowed for years 3, 5 and 7 for reading (by 12, 12 and 5 percentage points, respectively) and for years 3, 5 and 9 for numeracy (by 1, 7 and 7 percentage points, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Students meeting the national minimum standard in reading and numeracy, by Indigenous status, 2008 to 2022

This chart shows that the proportion of First Nations students meeting the national minimum standard for reading in Year 3 increased from 68% to 83% from 2008 to 2022, and the gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous students narrowed over the period.

Source: ACARA 2022 (National Assessment Program – Reading and Numeracy).

Programme for International Student Assessment

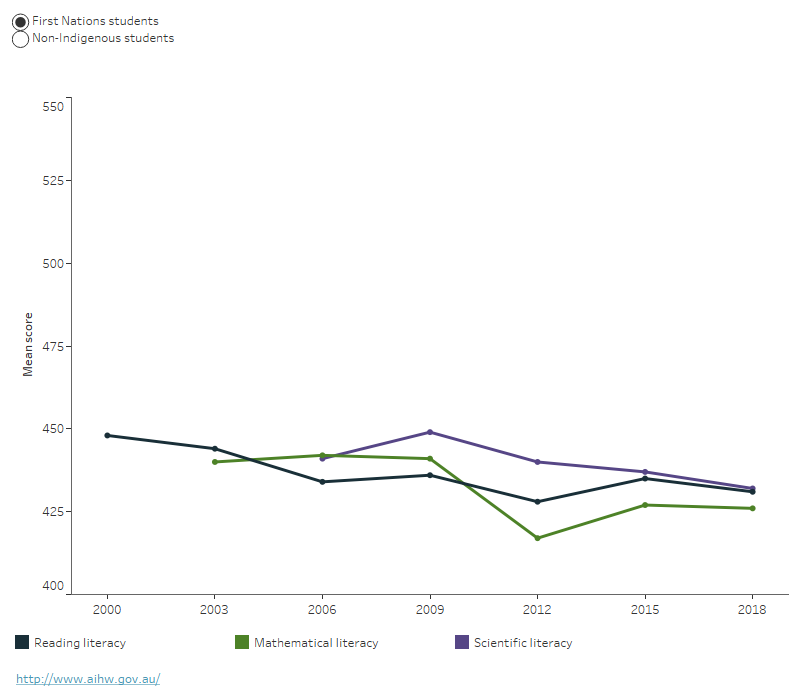

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a standardised test of knowledge and skills administered to a representative sample of 15-year-old students by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in over 70 countries. For more information on Australia’s results, see Primary and secondary schooling.

Due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 PISA test was deferred until 2022, and first results are expected to be published in late 2023 (OECD 2023).

Australia’s 2018 PISA results showed that:

- The proportion of First Nations students who met the National Proficient Standard (achieved a score above 480) was 32% for reading literacy, 27% for mathematical literacy, and 31% for scientific literacy.

- There was a decline in reading literacy for First Nations students from 2000 to 2018 (from a mean score of 448 to 431). There was no significant change over time for mathematical and scientific literacy. For non-Indigenous students, there was a decline over time in all domains (Figure 6).

- The mean score for First Nations students was 431 in reading literacy, 426 in mathematical literacy and 432 in scientific literacy. The mean scores for non-Indigenous students were 507, 495 and 507, respectively.

- The gap in the mean scores for scientific literacy between First Nations and non-Indigenous students narrowed from 2006 to 2018 (from 88 to 75). This can largely be attributed to a decline in the performance of non-Indigenous students.

Figure 6: PISA mean performance scores in reading, mathematical and scientific literacy, by domain and Indigenous status, 2000 to 2018

This chart shows that the mean performance score for reading literacy for First Nations students declined from 448 in 2000 to 431 in 2018, while the scores for mathematical literacy and scientific literacy stayed broadly stable. The reading literacy score for non-Indigenous students declined from 531 to 507 over the same period.

Note: The starting year for each domain is determined by the first cycle that a domain had a full assessment (the first cycle it was the major domain). This occurs every third cycle from the starting year. Reading literacy was the major domain in 2018.

Source: Thomson et al. 2019.

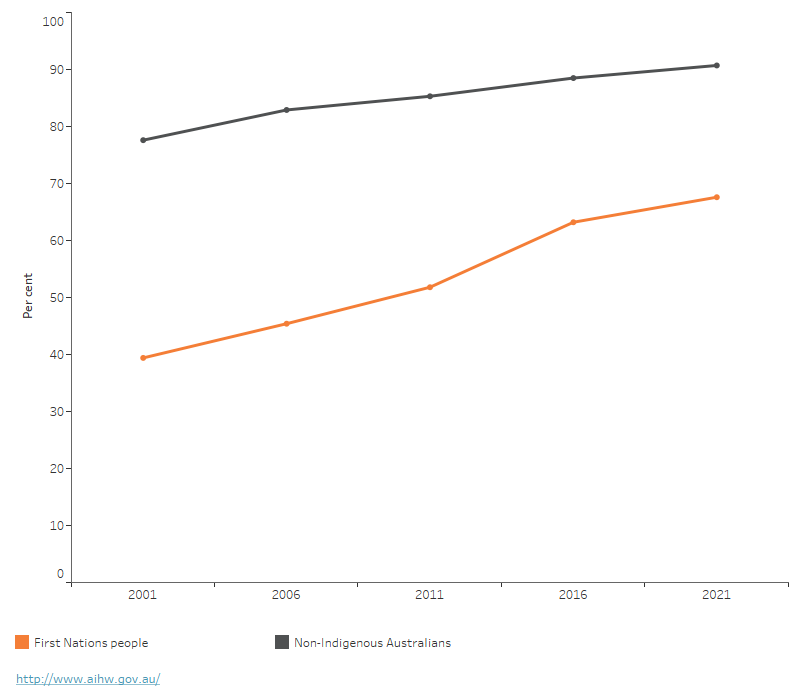

Attainment of Year 12 or equivalent

In the 2021 Census, the proportion of First Nations Australians aged 20–24 who had attained a Year 12 or equivalent qualification (Certificate III or above) was 68%, an increase of 16 percentage points from 2011. The rate for non-Indigenous Australians increased by 6 percentage points over the same period (from 85% in 2011 to 91% in 2021) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Proportion of people aged 20–24 who had attained a Year 12 or equivalent (Certificate III or above) qualification, by Indigenous status, 2001 to 2021

This chart shows that the proportion of First Nations Australians aged 20–24 who had attained a Year 12 or equivalent (Certificate III or above) was 39% in 2001 and increased to 68% in 2021. The rate for non-Indigenous Australians was 78% in 2001 and 91% in 2021. The gap between the two populations narrowed over the period.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2001–2021 (ABS 2021a).

The gap in Year 12 or equivalent (Certificate III or above) attainment rates for First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians aged 20–24 narrowed by around 10 percentage points over the decade to 2021 – from a gap of 36 percentage points in 2011 to around 23 percentage points in 2021.

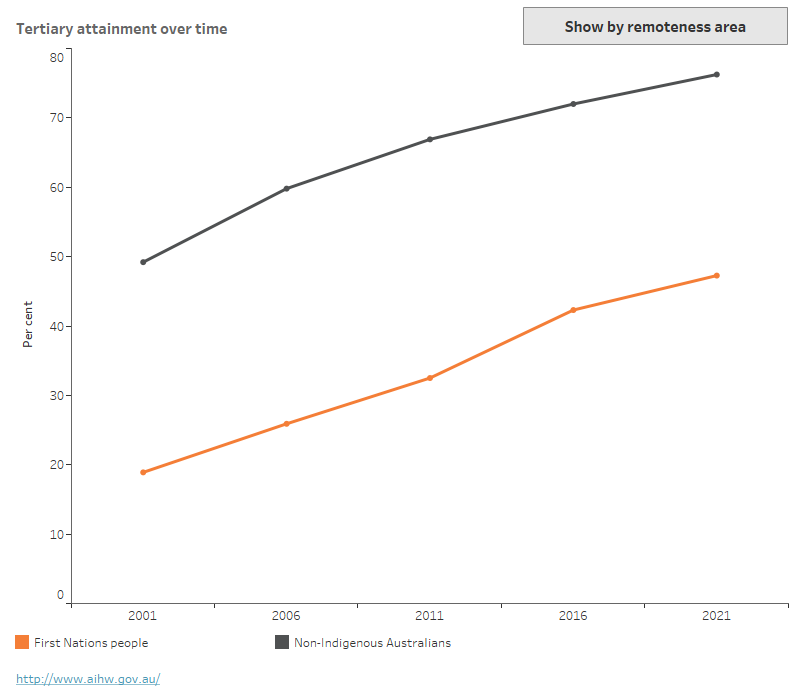

Tertiary qualifications

Based on data from the 2021 Census, 47% of First Nations Australians aged 25–34 had completed a tertiary qualification as their highest educational attainment (Certificate III and above). This was 76% for non-Indigenous Australians aged 25–34 (Figure 8). Completion rate for First Nations people ranged from 57% in Major cities to 18% in Very remote areas.

Figure 8: Proportion of people aged 25–34 who had attained Certificate III or above, by Indigenous status, 2001 to 2021

This chart shows that the proportion of First Nations Australians aged 25–34 who had attained a tertiary qualification (Certificate III or above) increased from 19% in 2001 to 47% in 2021. For non-Indigenous Australians the proportion increased from 49% in 2001 to 76% in 2021.

The second chart shows that in 2022, the proportion of First Nations Australians aged 25–34 who had attained a tertiary qualification (Certificate III or above) ranged from 57% in major cities to 18% in very remote areas. For non-Indigenous Australians, the rate ranged from 78% in major cities to 71% in remote areas.

NAPLAN 2023 Commentary Source: AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2001–2021 (ABS 2021a).

For First Nations students aged 34 and under in Certificate III or above government-funded Vocational education and training (VET) courses, enrolments increased by 11% from 33,400 in 2020 to 36,950 in 2021. This remains below the peak of 43,800 in 2019, before the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (NCVER 2022).

Improvements have been made in university enrolments and course completions for First Nations Australians in recent years. Between 2011 and 2021:

- the number of First Nations students enrolled in university doubled, from 11,800 to 24,000

- there was a 97% increase in the number of higher education course completions by First Nations students (from 1,800 to 3,500) (Department of Education 2023).

Despite this progress, First Nations Australians continue to be under‑represented in universities, comprising 2.4% of the domestic higher education student population, compared with 3.8% of the total Australian population (ABS 2022; Department of Education 2023). For more information on factors affecting university participation, see ‘Chapter 7 Relative influence of different markers of socioeconomic status on university participation’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights.

Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted all levels of the education system in Australia throughout lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, and the flow-on effects of these into 2022 and 2023. However, there is a shortage of research specifically on how First Nations students have been affected, and it will take some time before the full impact of these disruptions becomes clear (AITSL 2021).

The majority of Australian students experienced a rapid transition to home-based online learning due to school and university closures. Although children of essential workers and vulnerable students were still able to attend school, the vast majority of students used home-based learning. The response to COVID-19 emphasised persistent inequities experienced by vulnerable population groups (Drane et al. 2020). First Nations students across Australia were less likely to have access to reliable internet or digital technologies necessary for remote learning (Bennett et al. 2020; Walker et al. 2021).

The short-term COVID-19 response also included social distancing measures, travel restrictions, the closure of non-essential services, stimulus packages and free childcare for working parents (Storen et al. 2020). Many regular student assessments were cancelled or deferred during the lockdown period due to the disruption in student learning, including NAPLAN 2020 and PISA 2021. Other data sources, such as the National Early Childhood Education and Care Collection, limited the scope of their reporting and have significant sections of missing data for the years 2020 and 2021 (ABS 2021b).

These and many other complex factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic may shift trends in education data. Further assessments on the impact of COVID-19 on education for First Nations Australians will be made in the future as data allow.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on education and skills of First Nations people and on progress on the education-related Closing the Gap targets, see:

- Closing the Gap website

- Closing the Gap data dashboard

- Closing the Gap Report 2022.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2020:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2011) The Health and Welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, October 2010: links between education and health, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

ABS (2021a) Education and Training: Census, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

ABS (2021b) Preschool education, Australia, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

ABS (2022) National, state and territory population, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) (2022) National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy National Report for 2022, ACARA, accessed 25 May 2023.

ACARA (2023a) National Report on Schooling in Australia Data Portal: Student attendance, Sydney, ACARA, accessed 25 May 2023.

ACARA (2023b) 2023 NAPLAN Commentary, Sydney, ACARA, accessed 24 August 2023.

AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership) (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on teaching in Australia: A literature synthesis, AITSL, accessed 25 May 2023.

Bennett R, Uink B and Cross S (2020) ‘Beyond the social: Cumulative implications of COVID-19 for first nations university students in Australia’, Social Sciences & Humanities Open,2(1), doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100083.

Biddle N and Cameron T (2012) Potential factors influencing Indigenous education participation and achievement. Research report for the National Vocational Education and Training Research Program, National Centre for Vocational Education Research, accessed 25 May 2023.

Department of Education (2023) Selected higher education statistics – 2021 student data, Department of Education, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

DESE (Department of Education, Skills and Employment) (2022) Australian Early Development Census National Report 2021, DESE, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

Drane C, Vernon L and O’Shea S (2020) The impact of ‘learning at home’ on the educational outcomes of vulnerable children in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic, Literature Review prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University, Australia, accessed 25 May 2023.

Hart M, Moore M and Laverty M (2017) ‘Improving Indigenous Health through education’, The Medical Journal of Australia 207(1):11–12, doi:10.5694/mja17.00319.

NCVER (National Centre for Vocational Education Research) (2022) Australian vocational education and training statistics (VOCSTATS): Government funded students and courses 2021, NCVER, accessed 25 May 2023.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) (2023) Programme for International Student Assessment, PISA, OECD, Paris, accessed 25 May 2023.

Productivity Commission (2023) Closing the Gap information repository, Data dashboard: Socioeconomic outcome area 6, Productivity Commission website, accessed 3 August 2023

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) (2020) Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2020, Productivity Commission, Canberra, accessed 25 May 2023.

Storen R and Corrigan N (2020) COVID-19: a chronology of state and territory government announcements (up until 30 June 2020). Research paper series, 2020–21. Department of Parliamentary Services, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

Thomson S, De Bortoli L, Underwood C and Schmid M (2019) PISA 2018: Reporting Australia’s Results. Volume I Student Performance, Australian Council for Education Research, accessed 25 May 2023.

Walker R, Usher K, Jackson D, Reid C, Hopkins K, Shepherd C, Smallwood R and Marriott R (2021) ‘Connection to… Addressing digital inequities in supporting the well-being of young Indigenous Australians in the wake of COVID-19’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 2141, doi:10.3390/ijerph18042141.