Types of permanency outcome

Before a child enters care (preservation)

Preservation describes the aim of preventing unnecessary entry into out-of-home care for children who have an interaction with the child protection system. Through early intervention and effective family support, children are enabled to remain within their family where it is safe to do so.

Indicator 1.2 is a proxy measure for preservation. It reports on children aged 0–16 who were the subject of a substantiation and were not admitted to out-of-home care within 12 months of the substantiation. It is assumed that supports have been provided to the family to enable the child to remain safely at home. Data is reported for the previous financial year (2019–20) since the indicator covers the 12 months following the initial substantiation.

In 2019–20:

- Nearly 48,900 children were the subject of a substantiation and were not living in out-of-home care. Of these children, approximately 39,600 (81%) were not admitted to out-of-home care within 12 months of the substantiation (See Table S1.2).

- The proportion of children not admitted to out-of-home care within 12 months of a substantiation ranged from 61% in South Australia to 93% in New South Wales.

- Nearly 14,300 Indigenous children were the subject of a substantiation. Of these children, 10,900 (76%) were not admitted to out-of-home care within 12 months of the substantiation.

After a child enters out-of-home care

When preservation of families is not possible, permanency planning is initiated and the most suitable permanency outcome for the child is considered.

In Australia, most states and territories prioritise specific permanency-related actions and timeframes in children’s case planning. By incorporating permanency goals into a child’s case planning, jurisdictions can actively seek the most suitable immediate placement, while preparing for long‑term care arrangements and better developmental outcomes. The timeframe for reunification varies across jurisdictions, but for most jurisdictions, if a child is not reunified within 2 years, then a long-term, stable placement will be pursued. For more information see Appendix G of Child protection Australia 2018–19 (AIHW 2020).

Box 2: Permanency outcome exclusions

Children on long-term guardianship or custody orders are excluded from POPF indicators on reunification (Indicators 1.3 and 1.6a) as these placements are not generally the focus of reunification efforts.

Long-term guardianship or custody orders are used in recognition that for some children, especially those with complex needs or requiring ongoing case management, the best permanency outcome is a long-term placement in out-of-home care.

Reunification

Safe reunification of a child with their family is a policy priority for all states and territories (Fernandez 2014). The aim of reunification is to return a child home quickly and safely after time spent in care, and to enable that child to stay at home. This occurs when it is in the child’s best interest and where it will safeguard the child’s long-term stability and permanency (AIHW 2016).

Reunification is also a key part of state and territory governments implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (AIHW 2022).

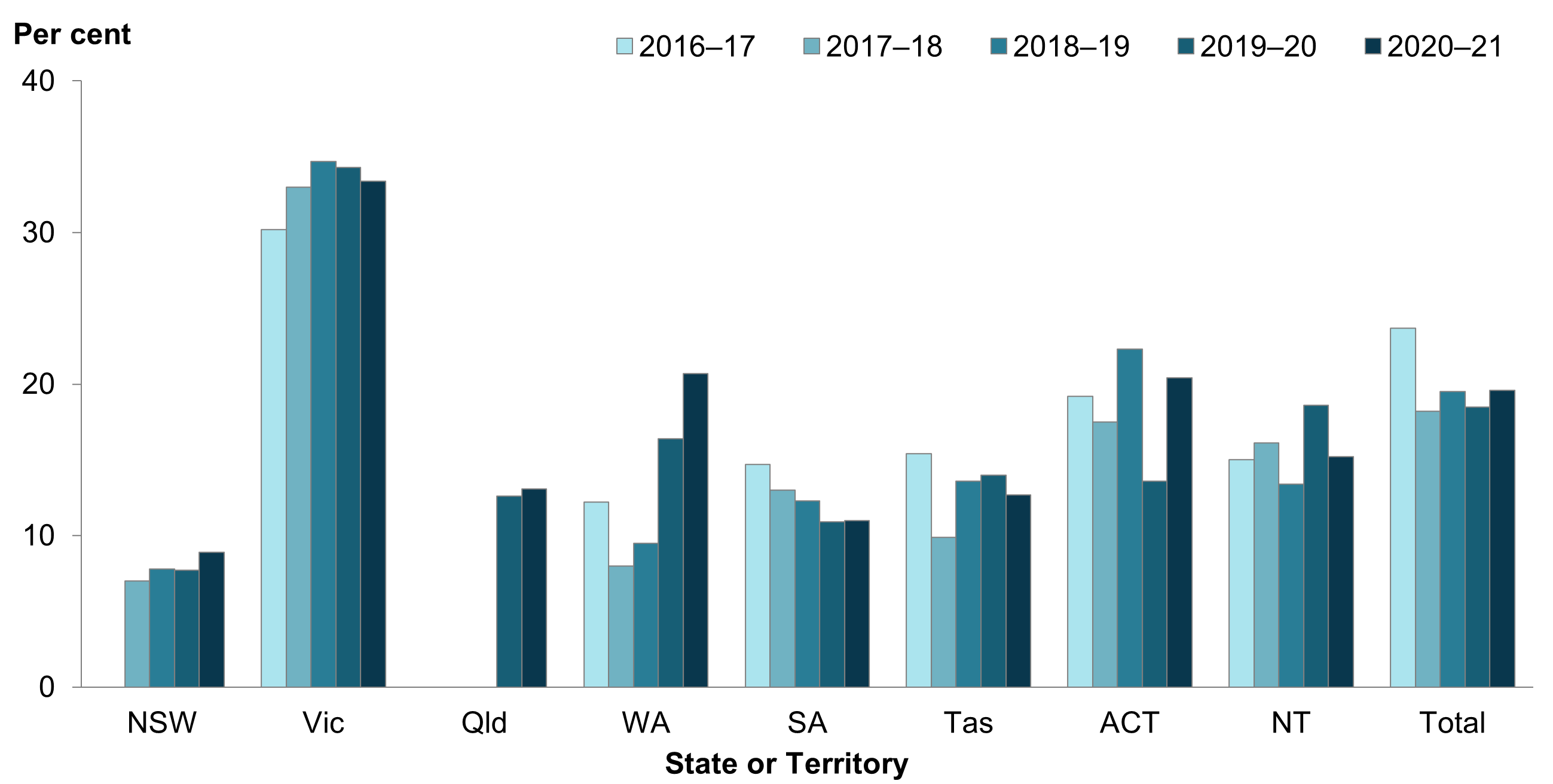

Indicator 1.3 measures the proportion of children aged 0–17 in out-of-home care (excluding children on long-term guardianship orders) who were reunified in the reporting period. This indicator is the same as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle Indicator 2.3 (AIHW 2022).

Note that data tables and the associated figure for this indicator include 5 years of data because the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle indicators report data since 2016–17.

In 2020–21:

- There were over 27,300 children in out-of-home care for whom reunification was a possibility. This excludes children in out-of-home care on long-term guardianship or custody orders (see Box 2). Of these children, 20% were reunified in the reporting period (Figure 1).

- Reunification rates ranged from 9% in New South Wales to 33% in Victoria.

- There were almost 10,300 Indigenous children in out-of-home care for whom reunification was a possibility. Reunification rates for Indigenous children have remained at or below 16%, after dropping from 18% in 2016–17.

Indicator 1.3 does not measure reunification success or the ongoing safety of the child. Children on long-term guardianship orders were excluded from this indicator as these children are not generally a focus for reunification efforts.

Figure 1: Children aged 0–17 in out-of-home care (excluding children on long-term guardianship orders) who were reunified, by state and territory, 2018–19 to 2020–21 (per cent) (Indicator 1.3)

Notes

- For New South Wales, reunification data were not available for 2016–17.

- For Queensland, reunification data were not available for 2016–17, 2017–18 and 2018–19.

- In Western Australia, reunification refers to a child being reunified with one or both parents. The term parent refers to a person, other than the Chief Executive Officer of the Department of Communities, who, by law, has responsibility for the day-to-day and long-term care, welfare and development of the child.

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW Child Protection Collection 2021 Table S1.3.

Third-party parental responsibility orders

After reunification, the next most utilised permanency outcome are third-party parental responsibility orders. These are a longer-term care arrangement where guardianship is granted to a third party who is not the minister/executive. For many children, they are pursued only when safe reunification is not possible, or when alternate care has been deemed the most suitable way to achieve stability for the child (Osmond and Tilbury 2012).

Indicator 1.4 measures the proportion of children aged 0–17 in out-of-home care who received a third-party parental responsibility order in the reporting period.

In 2020–21:

- Approximately 2% of the 55,000 children in out-of-home care received a third-party parental responsibility order. This proportion was similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children (Table S1.4).

- Rates of exit from out-of-home care to a third-party parental responsibility order ranged from 0% in the Northern Territory to 4% in Victoria.

Adoption

Children in out of home care with no plan to be reunited with their birth family can be adopted. Whether or not adoption is pursued as a permanency outcome is dependent on state and territory policy and practice (Butlinski et al. 2018).

For adoption to be pursued it generally must be assessed as the best option for the child. Consideration is given to the ability of prospective adoptee families to provide independently for the child for the rest of their life, as well as the rights of everyone involved being upheld (Ward et al. 2022).

Indicator 1.5 measures the proportion of children aged 0–17 in out-of-home care who were adopted by known carers, that is, the foster parents or other non-relatives who had been caring for the child in out-of-home care. In 2020–21 there were 94 known-carer adoptions from out-of-home care, equating to 0.2% of children in out-of-home care (Table S1.5).

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2016) Permanency planning in child protection, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 9 August 2022.

AIHW (2020) Child protection Australia 2018–19, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 15 June 2022.

AIHW (2022) The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle indicators, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 26 August 2022.

Butlinski A, Rowe H, Goddard C and Freezer N (2019) ‘The adoption of children from out-of-home care: how decision-makers explain the low rates of adoption in Victoria, Australia’, Journal of Public Child Welfare, 13(2):170–195, doi:10.1080/15548732.2018.1498428.

Fernandez E (2014) ‘Child protection and vulnerable families: trends and issues in the Australian context‘, Social Sciences, 3(4):785–808, doi:10.3390/socsci3040785.

Osmond J and Tilbury C (2012) ‘Permanency planning concepts’, Children Australia, 37(3):100–107, doi:10.1017/cha.2012.28.

Ward H, Moggach L, Tregeagle and Trivedi H (2022) Outcomes of open adoption from out-of-home care in Australia. Executive summary, Barnardos Australia, accessed 19 September 2022.