Health of children

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Health of children, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Health of children. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/health-of-children

MLA

Health of children. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 16 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/health-of-children

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health of children [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/health-of-children

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2024, Health of children, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/health-of-children

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Good health influences how children feel and go about their daily lives, as it can affect participation in family life, schooling, social and sporting activities. The foundations for good health start during the antenatal period and early years and can have long-term impacts on a child’s later life – see Health of mothers and babies. Targeting risk factors in children can reduce preventable chronic disease in adulthood and equip children with the best life chances (AIHW 2022a; Department of Health 2019). This page focuses on key health issues that children face. Precise age ranges used for reporting the health of children varies between data sources according to different frameworks, policies and legislation, but generally includes early childhood and early adolescence. For information about young people, see Health of young people.

Profile of children

At 30 June 2023, an estimated 4.8 million children aged 0–14 lived in Australia. Boys made up a slightly higher proportion of the population than girls (51% compared with 49%) (ABS 2023f).

The number of children in Australia is projected to reach 7.2 million by 2071 (ABS 2023h). However, due to sustained low fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, the number of children as a proportion of the entire population has steadily fallen, from 29% in 1968 to 18% in 2023 (ABS 2023f). The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions to Australian population trends and these changes may affect subsequent projections.

Australia’s children

In 2022, among all children aged 0–14:

- Almost 3 in 4 (72%) lived in Major cities (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023g).

- Nearly 1 in 5 (19%) lived in the lowest socioeconomic areas (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023g).

- Almost 1 in 10 (8%) were born overseas (ABS 2023b).

As of 30 June 2021, final Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) estimates indicate that 6.9% of children were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ABS 2023a).

Health status of children

Burden of disease

Burden of disease refers to the quantified impact of a disease or injury on a population, which captures overall health loss, that is, years of healthy life lost through premature death or living with ill health (see Burden of disease).

In 2023, for infants and young children aged under 5, the leading causes of total burden of disease were mainly infant and congenital conditions, and heart conditions, with similar leading causes for both boys and girls (Figure 1). Asthma was the leading cause of total burden among children aged 5–14 followed by 4 mental health conditions: autism spectrum disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders and conduct disorders (AIHW 2023b).

The leading causes of total burden among boys and girls aged 5–14 differed slightly, with autism spectrum disorders contributing the most burden to boys (16%) and asthma contributing the most to girls (11%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Leading causes of total burden among children aged 0–14, by age group and sex, 2023

The leading causes of burden for boys aged under 5 ranked from first to fifth were: pre-term birth and low birthweight complications, birth trauma and asphyxia, cardiovascular defects, sudden infant death syndrome and asthma. For boys aged 5–14, the leading causes from first to fifth were: autism spectrum disorders, asthma, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder and depressive disorders.

The leading causes of burden for girls aged under 5 ranked from first to fifth were: pre-term birth and low birthweight complications, birth trauma and asphyxia, cardiovascular defects, sudden infant death syndrome and asthma. For girls aged 5–14, the leading causes from first to fifth were: asthma, anxiety disorders , depressive disorders, autism spectrum disorder and conduct disorder.

Mental health

The most recent national data on child and adolescent mental health is from the 2013–14 Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (also known as the Young Minds Matter survey). Modelling was used to update these estimates. To explore this in more detail, see Regional estimates of children and adolescent mental disorders.

In 2013–14, 1 in 7 (14%) children aged 4–11 experienced a mental disorder in the 12 months prior to the survey. Boys were more commonly affected than girls (17% compared with 11%), particularly in relation to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (11% compared with 5.4%) (Table 1) (Lawrence et al. 2015).

| Disorder | Boys (%) | Girls (%) | All children (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

ADHD | 10.9 | 5.4 | 8.2 |

Anxiety disorders | 7.6 | 6.1 | 6.9 |

Conduct disorder | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 |

Major depressive disorder | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

Any mental disorder(a) | 16.5 | 10.6 | 13.6 |

(a) Totals are lower than the sum of disorders as children may have had more than 1 class of mental disorder in the previous 12 months.

Source: Lawrence et al. 2015.

Among children aged 4–11 with some form of mental disorder:

- Almost 3 in 4 (72%) had mild disorders, 1 in 5 (20%) had moderate disorders and around 1 in 12 (8.2%) had severe disorders.

- Severe disorders were more common among boys (9.9%) than girls (5.6%) (Lawrence et al. 2015).

For more information, see Mental health.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health

Various research projects confirm the COVID-19 pandemic impacted on the mental health of Australia’s children in many ways.

- In October 2021, a review of research undertaken since the COVID-19 pandemic began found substantial deterioration of children’s mental health, particularly during periods of lockdown and for children with pre-existing conditions and families in financial distress (Renshaw and Seriamlu 2021).

- In August 2021, as part of the Australian National University Centre for Social Research and Methods’ COVID-19 Impact Monitoring Survey Program, nearly 2 in 3 (61%) parents/carers of children aged 2 and over reported experiencing a negative impact on their child’s mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Biddle et al. 2021). The proportion of children aged 3–17 who experienced any negative effect had increased as the pandemic continued (Biddle et al. 2021).

- In a survey in September 2020, parents/carers reported that more than 1 in 3 children aged 5–18 (35%) experienced a negative impact on their mental health (RCHpoll 2021). Around 3 in 10 (29%) of children in New South Wales, 1 in 5 (21%) in Victoria and other states and territories (21%) reported a positive impact (RCHpoll 2021).

Disability

Data sources on disability

The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) collects a broad range of information about people with disability including levels of severity, and is the most detailed and comprehensive source of Australian disability data (ABS 2022b).

The 2018 SDAC provides the latest available data on the prevalence and experiences of disability among Australian children. Data from the 2022 SDAC is expected to be available from June 2024.

The 2021 Census of Population and Housing collected information on whether a person has a profound or severe core activity limitation, and requires assistance in their day to day lives in one or more of the 3 core activity areas of self-care, mobility and communication due to a long term health condition, a disability or old age (ABS 2022a).

The prevalence of disability has remained relatively stable over time for children. Since 2003, there has been little change in the prevalence for children aged 0–4 (4.3% in 2003 compared with 3.7% in 2018) or children aged 5–14 (10% in 2003 compared with 9.6% in 2018) (ABS 2019a).

According to the 2018 SDAC:

- Around 1 in 13 (7.6% or an estimated 356,000) Australian children aged 0–14 have disability (ABS 2019b).

- More boys (9.6%) than girls (5.7%) have disability and 7.8% (an estimated 241,000) of children aged 5–14 had a schooling restriction.

- Schooling restrictions are determined based on whether a person needs help, has difficulty participating, or uses aids or equipment in their education because of their disability.

- Boys aged 5–14 were more likely than girls to have a schooling restriction (9.9% compared with 5.6%).

Based on self-reported data from the 2021 Census, around 1 in 25 (3.5%, or an estimated 160,000) children aged 0–14 had a profound or severe core activity limitation (ABS 2022a).

Chronic conditions

Chronic conditions, also known as long-term conditions or non-communicable diseases, refer to a wide range of conditions, illnesses and diseases that tend to be long-lasting with persistent effects. Chronic disease can interrupt a child’s normal development and can increase the risk of being developmentally vulnerable at school entry (AIHW 2022a; Bell et al. 2016).

According to self-reported data from the ABS 2022 National Health Survey (NHS), an estimated 2 in 5 (45%) children aged 0–14 had one or more chronic condition (ABS 2023c).

According to the 2022 NHS, the most common chronic conditions among children aged 0–14 did not change markedly from the 2021 NHS, and were:

- hay fever and allergic rhinitis (13%) and asthma (8.2%), both diseases of the respiratory system

- allergies (including food, drug and undefined) (10%)

- anxiety related disorders (8.6%) and problems of psychological development (7.0%); both mental and behavioural conditions (ABS 2023c).

For more information, see chronic conditions and multimorbidity

Injuries

In 2021–22, there were around 62,500 injury hospitalisations among children aged 0–14, a rate of around 1,300 per 100,000 children (AIHW 2023c). Hospitalised injury cases exclude presentations to emergency departments that are not admitted to hospitals. For more information on non-admitted patient services, see Hospitals.

Overall, boys were 1.5 times as likely as girls to sustain an injury that resulted in hospitalisation (around 1,500 and 1,100 per 100,000, respectively) (AIHW 2023c). These differences varied by age, from 1.4 times as likely for children aged 0–4 to 1.8 times for 10–14-year-olds.

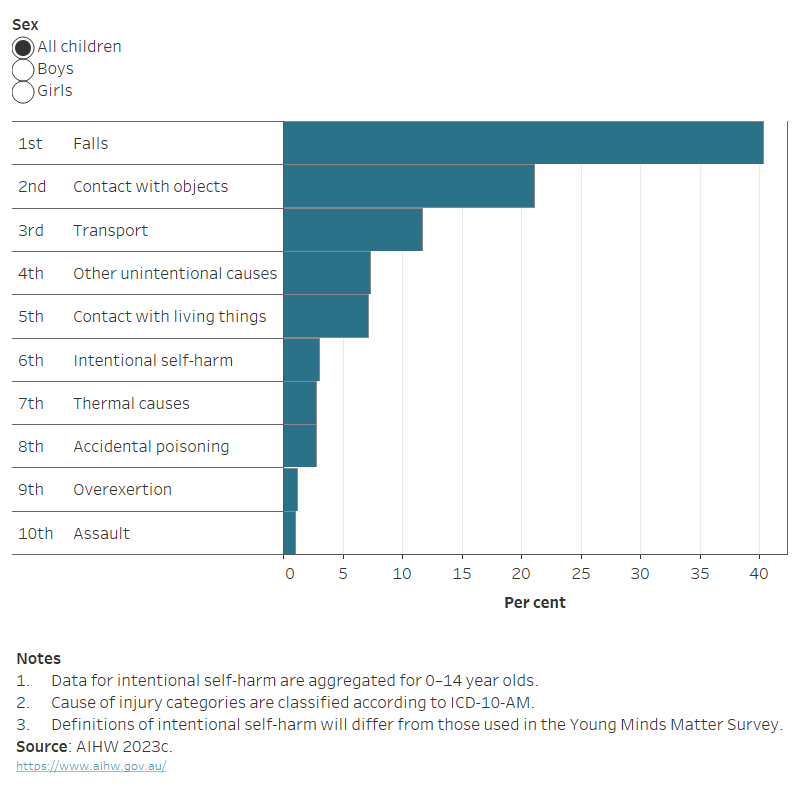

In 2021–22, the leading causes of injury hospitalisations among children were falls, contact with objects (such as being struck or cut by something other than another human or animal) and transport accidents (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Injury hospitalisations for children aged 0–14, by leading causes of injury, 2021–22

The horizontal bar chart shows that falls followed by contact with objects and transport accidents were the leading causes of injury hospitalisations across all children.

During 2019–2021, injuries contributed to 527 deaths of children aged 0–14, a rate of 3.7 per 100,000 children (AIHW 2023e).

For more information, see Injury

Deaths

In 2022, there were 958 deaths of infants under the age of one, a rate of 3.2 per 1,000 live births (ABS 2023i). Infant deaths accounted for 2 in 3 (67%) deaths among all children aged 0–14. The leading causes of infant deaths in 2022 were similar to those reported in 2021: perinatal conditions (53%), congenital conditions (26%) and symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions, including Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (11%) (ABS 2023i). The infant death rate fell from 5.0 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1998 to 3.2 per 1,000 in 2020 (AIHW 2022a).

In 2022, there were 472 deaths of children aged 1–14, a rate of 10.6 per 100,000 children. The leading causes of child deaths were: land transport accidents (10%), certain conditions originating in the perinatal conditions (7.6%) and malignant brain tumours (6.8%) (ABS 2023i). The death rate for children aged 1–14 fell from 19.7 deaths per 100,000 in 1998 to 8.6 per 100,000 in 2020 (AIHW 2022a).

For more information, see Life expectancy and causes of death.

Health risk factors of children

Nutrition

As children are constantly growing, good nutrition is key to support their growth and development, and it gives them the energy they need to concentrate, learn and play (NHMRC 2013). A healthy diet also:

- supports children’s physical and cognitive development

- helps to prevent overweight and obesity

- helps to maintain a healthy weight

- increases quality of life

- protects against infection

- protects against the development of chronic conditions in adulthood (AIHW 2022a; WHO 2018).

The ABS 2022 National Health Survey (NHS) reported on children’s fruit and vegetable consumption among 2–14 year olds (ABS 2023e).

According to self-reported data from the 2022 NHS:

- Around 7 in 10 (69%) children aged 2–14 met the serve recommendation for fruit

- 1 in 20 (4.8%) children aged 2–14 met the serve recommendation for vegetables (ABS 2023e).

It was also estimated that 17% of children aged 2–14 consumed sugar-sweetened drinks and 8% of children consumed diet drinks at least once a week.

For more information, see Diet.

Physical activity

In addition to good nutrition, participating in physical activity and limiting sedentary behaviour is critical to a child’s health, development and psychosocial wellbeing. The most recent data available on physical activity and sedentary screen time for children are self-reported from the ABS 2011–12 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS). The NNPAS is scheduled to be conducted again in 2023 as part of the Intergenerational Health and Mental Health Study.

In 2011–12, among children aged 2–4:

- Most (72%) met the recommended 180 minutes of physical activity each day.

- Just over one-quarter (26%) met the screen-based activity guideline of no more than 60 minutes per day (ABS 2013).

In 2011–12, among children aged 5–14:

- Less than one-quarter (23%) undertook the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity every day.

- Less than one-third (32%) met the screen-based activity guidelines.

- One in 10 (10%) met both sets of guidelines each day (ABS 2013).

On average, children aged 5–14 spent around 2 hours (123 minutes) each day sitting or lying down for screen-based activities, with 3.5 minutes of this being for homework. Children aged 10–14 spent more time in front of screens (145 minutes) on average in a day than children aged 5–9 (102 minutes) (ABS 2013).

For more information, see Physical activity.

Overweight and obesity

Overweight and obesity (the abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat in the body), increases a child’s risk of poor physical health and is a risk factor for illness and mortality in adulthood. Overweight and obesity generally results from a sustained energy imbalance, where the amount of energy a child consumes through eating and drinking outweighs the energy they expend through physical activity and bodily functions (AIHW 2022a).

Based on measured height and weight data from the 2022 NHS, among children aged 2–14, around:

- 2 in 3 (66% or an estimated 2 million) were normal weight

- 1 in 4 (26% or an estimated 1 million) were overweight or obese

- 1 in 13 (7.7%) were obese (ABS 2023d).

The prevalence of overweight and obesity was similar for boys and girls across age groups, and remained relatively stable between 2011–12 and 2022 (ABS 2023d).

For further detail of how overweight and obesity is defined and measured, see Overweight and obesity.

Health care of children

Immunisation

Measuring childhood immunisation coverage helps track how protected the community is against vaccine-preventable diseases, and reflects the capacity of the health care system to effectively target and provide vaccinations to children. Fully immunised status is measured at ages 1, 2 and 5 and means that a child has received all the scheduled vaccinations appropriate for their age (AIHW 2022b).

In 2022, more than 9 in 10 (92%) children aged 2 were fully immunised. Coverage rates for 2-year-olds are slightly lower than for 1-year-olds (94%) and 5-year-olds (94%) due to changes to the National Immunisation Program Schedule in December 2014 and March 2017 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023).

The proportion of children fully immunised at 2 years old was relatively stable at around 91–93% between 2009 and 2022, dropping slightly to 89% in 2015 and 90% in 2017 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023).

For more information, see Immunisation and vaccination.

Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services

In 2021–22, children aged 0–11 made up 5.2% (145,000) of all people receiving Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services (note that an individual may receive a service from more than one type of provider and can be counted more than once). Adults aged 25–34 made up the greatest proportion of patients (21%) (590,000) (AIHW 2023e). The most common provider type for children aged 0–11 was general practitioners (78%) (AIHW 2023e).

COVID-19 impact on mental health services

In August 2021, a survey of parents and carers of children aged 0–18 found that around 1 in 5 (21%) needed mental health support for their children and 73% of those sought help (Biddle et al. 2021). Of those who sought help, 2 in 5 (40%) reported it was difficult or very difficult to access mental health support services for their child.

Kids Helpline reported that nationally the number of duty of care interventions to protect children and young people between December 2020 and 31 May 2021 was nearly twice as high as the same period a year ago (yourtown 2021). This increase in contact to police, child safety or ambulance services was largely due to interventions for suicide attempts (38%) and child abuse (35%).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on the health of children, see:

- Australia’s children

- National Action Plan for the Health of Children and Young People: 2020–2030

- National framework for protecting Australia’s children indicators

- Children’s Headline Indicators

- Glossary

For more on this topic, visit Children & youth.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2013) Microdata: Australian Health Survey: nutrition and physical activity, 2011–12, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 23 July 2020.

ABS (2019a) Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, ABS website, accessed 11 February 2022.

ABS (2019b) Microdata: Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 15 September 2021.

ABS (2022a) Disability and carers: Census [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 17 March 2023.

ABS (2022b) Understanding disability statistics in the Census and the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers, ABS website, accessed 27 March 2023.

ABS (2023a) Estimates of resident Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, non-indigenous and total populations, States and territories – 30 June 2021 [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 23 February 2024.

ABS (2023b) Estimated resident population, country of birth, age and sex – as at 30 June 1996 to 2022, ABS.Stat Data explorer website, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2023c) National Health Survey 2022- Table 3: Long term health conditions, by age and sex [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 12 February 2024.

ABS (2023d) National Health Survey 2022- Table 17: Childrens Body Mass Index, waist circumference, height and weight, by age and sex [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 12 February 2024.

ABS (2023e) National Health Survey 2022 – Table 18: Childrens consumption of fruit and vegetables, by age and sex [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 12 February 2024.

ABS (2023f) National, state and territory population – June 2023, ABS website, accessed 22 December 2023.

ABS (2023g) Population estimates by age and sex, by SA2, 2022 [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2023h) Projected population, Australia, 2022-2071 ABS.Stat Data explorer website, accessed 12 March 2024.

ABS (2023i) Underlying causes of death (Australia) [data set], abs.gov.au, accessed 12 February 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022a) Australia’s children, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 25 February 2022.

AIHW (2022b) Immunisation and vaccination, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 1 March 2024.

AIHW (2023b) Data tables: Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023 National estimates for Australia [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 12 February 2024.

AIHW (2023c) Data tables A: Injury hospitalisations, Australia 2021–22 [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 13 February 2023.

AIHW (2023d) Data tables: Medicare-subsidised mental health-specific services 2021–22 [data set], aihw.gov.au, accessed 27 April 2023.

AIHW (2023e) National Mortality Database (NMD), AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 2 June 2023.

Bell MF, Bayliss DM, Glauert R, Harrison A and Ohan JL (2016) ‘Chronic illness and developmental vulnerability at school entry’, Pediatrics, 137(5):e20152475, doi:10.1542/peds.2015-2475.

Biddle N, Edwards B, Gray M and Sollis K (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on child mental health and service barriers: The perspective of parents – August 2021, Australian National University Centre for Social Research and Methods, accessed 23 February 2022.

Department of Health (2019) National action plan for the health of children and young people: 2020–2030, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 13 April 2022.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Historical coverage data tables for all children, health.gov.au, accessed 24 April 2023.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven De Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J and Zubrock SR (2015) The mental health of children and adolescents - Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 11 February 2022.

NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) (2013) Australian Dietary Guidelines, NHMRC website, accessed 14 February 2022.

RCHpoll (The Royal Children’s Hospital National Child Health Poll) (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on the lives of Australian children and families, The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, accessed 23 February 2022.

RCHpoll (2021) Remote learning: Experiences of Australian families, Poll 19 Supplementary report, The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, accessed 24 February 2022.

Renshaw L and Seriamlu S (2021) Australian Children and Young People’s Knowledge Acceleration Hub – Sector adaptation and innovation shaped by COVID-19 and the latest evidence on COVID-19 and its impacts on children and young people Sep/Oct 2021 Digest, ARACY and UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) Australia, accessed 23 February 2022.

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2020) Healthy diet (who.int), WHO, Geneva, accessed 29 June 2023.

yourtown (2021) New Kids Helpline data reveals spike in duty of care interventions – Media release 9 Jun 2021, yourtown, accessed 24 February 2022.

This page was last updated 16 April 2024. All information on this page is the most recent available, as at that date.