Summary

Family, domestic and sexual violence is a major health and welfare issue. It occurs across all ages, and all socioeconomic and demographic groups, but predominantly affects women and children.

This report explores the latest data available to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare on family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia. It brings together information from multiple sources on victims and perpetrators and on the causes, impacts and outcomes of violence. Gathering this information highlights notable data gaps which, if filled, could strengthen the evidence base and support the prevention and reduction of family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia.

As many data collections focus only on violence perpetrated by an intimate partner, particularly male violence against women, much of this report focuses on domestic violence.

Family violence refers to violence between family members, typically where the perpetrator exercises power and control over another person. The most common and pervasive instances occur in intimate (current or former) partner relationships and are usually referred to as domestic violence. Sexual violence refers to behaviours of a sexual nature carried out against a person’s will. It can be perpetrated by a current or former partner, other people known to the victim, or strangers.

Women are at greater risk of family, domestic and sexual violence

Women are at greater risk of family, domestic and sexual violence

Men are more likely to experience violence from strangers and in a public place; women are most likely to know the perpetrator (often their current or a previous partner) and the violence usually takes place in their home.

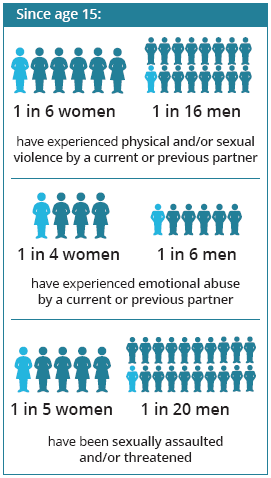

One in 6 Australian women and 1 in 16 men have been subjected, since the age of 15, to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or previous cohabiting partner (ABS 2017b). Family, domestic and sexual violence happens repeatedly—more than half (54%) of the women who had experienced current partner violence, experienced more than one violent incident (ABS 2017b). However, between 2005 and 2016, rates of partner violence against women have remained relatively stable (ABS 2006, 2017b).

In 2014–15, on average, almost 8 women and 2 men were hospitalised each day after being assaulted by their spouse or partner (AIHW 2017b). From 2012–13 to 2013–14, about 1 woman a week and 1 man a month were killed as a result of violence from a current or previous partner (Bryant & Bricknell 2017).

Almost 1 in 4 (23%) women and 1 in 6 (16%) men have experienced emotional abuse from a current or previous partner since the age of 15 (ABS 2017b).

Almost 1 in 5 women (18%) and 1 in 20 men (4.7%) have experienced sexual violence (sexual assault and/or threats) since the age of 15. Women were most likely to experience sexual violence from a previous cohabiting partner (4.5% of women) or a boyfriend/girlfriend or date (4.3% of women) (2017b). In 2016, on average, police recorded 52 sexual assaults each day against women and about 11 against men (ABS 2017d).

Some groups are more vulnerable

Some groups of people are at greater risk of family, domestic and sexual violence, particularly Indigenous women, young women, pregnant women, women separating from their partners, women with disability and women experiencing financial hardship.

Women and men who experienced abuse or witnessed domestic violence as children (before the age of 15) are also at increased risk.

Nearly 2.1 million women and men witnessed violence towards their mother by a partner, and nearly 820,000 witnessed violence towards their father, before the age of 15. People who, as children, witnessed partner violence against their parents were 2–4 times as likely to experience partner violence themselves (as adults) as people who had not (ABS 2017b). ).

Most at risk:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women

- Young women

- Pregnant women

- Women with disabilities

- Women experiencing financial hardships

- Women and men who experienced abuse or witnessed domestic violence as children.

Children are often exposed to the violence

Children are often exposed to the violence

There are limited data on the nature, extent and impacts of family violence on children. Despite this, qualitative research has shown that children exposed to family, domestic and sexual violence can experience long-term effects on their development and have increased risk of mental health issues, and behavioural and learning difficulties (Campo 2015).

Children can experience family violence as a witness and/or a victim. More than two-thirds (68%) of mothers who had children in their care when they experienced violence from their previous partner said their children had seen or heard the violence (ABS 2017b). As well, 1 in 6 (16%, or 1.5 million) women reported having experienced physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15 (as girls), and 1 in 9 (11%, or 992,000) men reported having experienced this abuse when they were boys (ABS 2017b).

Most behaviours identified as child abuse fall under the broad definition of family violence. In 2015–16, about 45,700 children were the subject of a child protection substantiation (investigated notification where there is sufficient evidence of abuse or neglect). A large and growing number of children are placed in out-of-home care as a consequence of this abuse (55,600 children in 2015–16) (AIHW 2017a).

The toll of family, domestic and sexual violence is substantial

The toll of family, domestic and sexual violence is substantial

Family and domestic violence can have far-reaching consequences. It is a leading cause of homelessness for women with children. In 2016–17, about 72,000 women, 34,000 children and 9,000 men seeking homelessness services reported that family and domestic violence caused or contributed to their homelessness (AIHW 2017d).

Intimate partner violence also has serious impacts on women’s health. In 2011, it contributed to more burden of disease (the impact of illness, disability and premature death) than any other risk factor for women aged 25–44. Mental health conditions were the largest contributor to the burden due to physical/sexual intimate partner violence, with anxiety disorders making up the greatest proportion (35%), followed by depressive disorders (32%) (Ayre et al. 2016). In 2015–16, the financial cost of violence against women and their children in Australia was estimated at $22 billion (KPMG 2016).

It is likely that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, pregnant women, women with disability, and women experiencing homelessness were underrepresented in this calculation. Accounting for these women may add another $4 billion (KPMG 2016).).

Family violence is worse for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Family violence occurs at higher rates for Indigenous Australians than for non-Indigenous Australians. Family violence within Indigenous communities needs to be understood as both a cause and effect of social disadvantage and intergenerational trauma (ABS 2016).

- In 2014–15, 1 in 7 (14%) Indigenous women experienced physical violence in the previous year. Of these, about 1 in 4 (28%) reported that their most recent incident was perpetrated by a cohabiting partner (ABS 2016).

- From 2012–13 to 2013–14, 2 in 5 Indigenous homicide victims (41%) were killed by a current or previous partner, twice the rate of non-Indigenous victims (22%) (Bryant & Bricknell 2017).

- In 2014–15, Indigenous women were 32 times as likely to be hospitalised due to family violence as non-Indigenous women, while Indigenous men were 23 times as likely to be hospitalised as non-Indigenous men (SCRGSP 2016).

- In 2015–16, Indigenous children were 7 times as likely to be the subject of substantiated child abuse or neglect as non-Indigenous children (AIHW 2017a).

There are data gaps in key areas, including for victims, perpetrators and at-risk groups

Although much is known about many aspects of family, domestic and sexual violence, there are several data gaps that need to be filled to present a comprehensive picture of its extent and impact in Australia. Specifically, there is no, or limited, data on:

- children’s experiences, including attitudes, prevalence, severity, frequency, impacts and outcomes of these forms of violence

- specific at-risk population groups, including Indigenous Australians, people with disability, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people, including those in same-sex relationships

- the effect of known risk factors, such as socioeconomic status, employment, income and geographical location

- services and responses that victims and perpetrators receive, including specialist services, mainstream services and police and justice responses

- pathways, impacts and outcomes for victims and perpetrators

- the evaluation of programs and interventions.

What needs to be done to fill the gaps?

A number of actions can be taken to improve current data collection, quality and comparability, and to fill data gaps. These include:

- analysing and using existing data—for example, further analysis at local geographical levels

- sharing existing, yet unpublished, data across government agencies, while protecting individual privacy

- developing a common and consistent definition, or set of definitions, to improve identification and measurement across data sets

- enhancing data collection to better understand people at risk and the services they need and use

- increasing the use of data linkage and longitudinal surveys to better understand pathways and outcomes for victims and perpetrators.

Priority data gaps will be further refined in consultation with stakeholders.

- Better data sharing

- Standard definitions

- Linking data

- Enhanced data collection

Summary

Introduction

- What is family, domestic and sexual violence?

- How is family, domestic and sexual violence measured? What are the data sources used in this report?

- How is this report structured?

Context for family, domestic and sexual violence

- What data are available to measure contextual factors? What do the data tell us?

- What is missing?

- How are we trying to change attitudes to violence?

Who is at risk of family, domestic and sexual violence?

- What data are available to report on risks?

- What do the data tell us?

- What is missing?

How is family, domestic and sexual violence experienced?

- What data are available to report on experiences?

- What do the data tell us?

- What is missing?

What are the responses to family, domestic and sexual violence?

- What data are available to report on responses?

- What do the data tell us?

- What is missing?

What are the impacts and outcomes of family, domestic and sexual violence?

- What data are available to report on impact and outcomes?

- What do the data tell us?

- What is missing?

What is known about family violence among Indigenous Australians?

- What data are available to report on family violence among Indigenous Australians?

- What are the attitudes of Indigenous Australians towards violence?

- What are the experiences of family violence?

- What are the risk factors for family violence?

- What are the responses to family violence?

- What are the impacts and outcomes of family violence?

- What is missing?

What are the key data gaps?

- Existing data sources for reporting on family, domestic and sexual violence

- What can be done to improve the evidence?

- New developments and emerging issues

End matter: Acknowledgments; Abbreviations; Glossary; References; List of tables; List of figures; List of boxes; List of In Focus; Appendix A: Data sources