Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease are preventable

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) are both preventable diseases. They are common in low- and middle-income countries, and among population groups living in poor socioeconomic conditions in high-income countries (Wyber & Carapetis 2015; Webb et al. 2015). ARF and RHD are caused by aspects of socioeconomic disadvantage, such as household crowding, socioeconomic deprivation, low levels of functioning ‘health hardware’ (for example, toilets, showers, taps) and lack of access to health care services (Webb et al. 2015; Sims et al. 2016). Improved living conditions and access to functional health hardware can reduce high rates of Strep A infections (Katzenellenbogen et al. 2017).

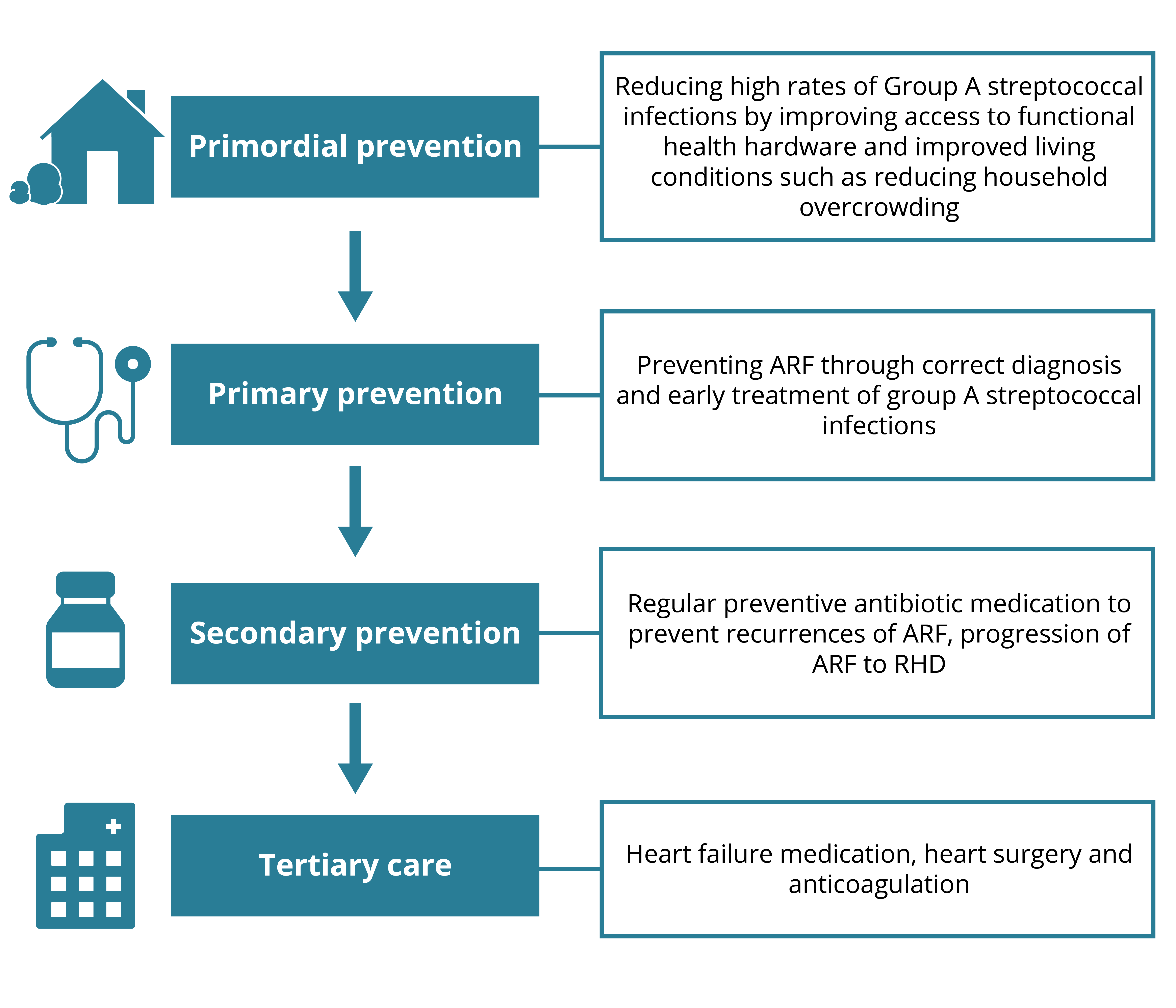

Several opportunities exist to interrupt the disease pathway from Strep A infection to ARF and then RHD (Figure 1.2). Prevention measures that improve living conditions and environmental health and address eradication of group A streptococcal infections are primordial prevention measures.

ARF is also preventable through early treatment of Strep A infections with penicillin. This is called primary prevention and relies on correct diagnosis and treatment of skin and throat infections with antibiotics as soon as possible after onset of symptoms. Timeliness of diagnosis and subsequent treatment can be negatively affected by health service access issues and delayed presentation to health services. The effectiveness of primary prevention is also compromised when the prescribed treatment does not comply with clinical guidelines (RHDAustralia 2020). Secondary prevention of the progression from ARF to RHD relies on accurate diagnosis of ARF, to enable commencement of regular antibiotic preventive medication. Correct diagnosis is challenging as there is no specific single laboratory test for ARF, and it can be misdiagnosed. Diagnosis is based on clinical criteria outlined in the Australian modification of the Jones criteria, which take into account Australia's high-risk groups (Technical notes – Table T1; RHDAustralia 2020 Chapter 6).

For people with suspected or clinically confirmed ARF episodes, intramuscular injection of benzathine benzylpenicillin G (BPG) is recommended every 21 to 28 days in order to prevent further Strep A infections and thereby reduce the risk of developing recurrent ARF. Although the injection causes significant patient discomfort and inconvenience, BPG prophylaxis is by far the only clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for RHD control at both individual and community levels (Webb et al. 2015; Wyber & Carapetis 2015; RHDAustralia 2020). Tertiary care aims to slow disease progression and prevent complications associated with RHD and can include surgery to repair or replace damaged heart valves once RHD is established (Noonan 2020).

The RHD Endgame Strategy: the blueprint to eliminate rheumatic heart disease in Australia by 2031 (Wyber et al. 2020) estimated that implementing a range of strategies aimed at reducing household crowding, improving hygiene infrastructure, strengthening primary health care, and enhancing the delivery of secondary prophylaxis, would reduce ARF and RHD cases by 69% and 71%, respectively.

Figure 1.2: ARF and RHD prevention measures

Chart: AIHW. Source: AIHW

This brave heart… This deadly heart… By Hayley S Kirk

I am inviting you into a story. And while it is our story, it is mostly Skout’s story and how his brave heart led us on a journey to learn of a deadly heart story that just might be one of our Country’s biggest, most shameful health issues.

Skout Wylie Kirk…

Skout is the youngest of my 5 children.

The day before Skout was to turn 10 years old – 7th May 2022 - he limped from school. His ankle and foot ballooning out over the top of his sock and – the ankle close to double the size of what it should normally be. When we got home, I administered ice, elevation and compression and gave him some Nurofen for the aching pain and an antihistamine just in case. By bedtime Skout’s other ankle began to swell and too his wrists and hands. Within 24 hours every possible joint on his body was swollen, aching and multiple pox-wart-like bumps had appeared on his elbows. It became so overwhelming for his inflamed body that he had lost his appetite, declining even birthday cake.

Living in Sydney it can be easily taken for granted how close and accessible a world leading children’s hospital is to our home. On presentation at the emergency department Skout was wheeled straight through for examination and so it began the repetition of every little detail of the, what, why, how, where, when of Skout’s days was scrutinised. Calming and consoling my frightened little boy while holding my breath waiting to hear negative results to the scary stuff like lymphoma and leukemia…exhale.

“Has Skout always had a murmur in his heart?” He hadn’t had a murmur…Ever. Besides recurring ear infections and tonsilitis which saw them be removed at age four and grommets in at two, my bunanay budyarra [little boy] was a healthy happy and very active child. It was a young resident doctor doing his rotation with the rheumatology team that put the pieces together. Swollen joints, rheumatic pox rash, changed heart rhythm and Strep A markers in the blood that had climbed from a usual 100 to close to 2000! After Chest x-rays, a long and detailed ultrasound on the heart, Skout was given pain relief and high dosage of anti-inflammatory medication and was admitted to hospital with suspected ARF [Acute Rheumatic Fever] – not seen at Sydney Children’s Hospital for nearly 40 years!

ARF primarily affects the heart, joints, and central nervous system. Of these symptoms, the autoimmune cardiac sequelae are the most dreaded for it causes fibrosis of heart valves, leading to crippling valvular heart disease, heart failure, strokes, endocarditis, and death. To hear and comprehend this was happening to my child was highly distressing and baffling. I’m not going to lie, I had never heard of ARF and innocently asked was it an old-fashioned illness like Scarlet Fever and quote, ‘like from Little House on the Prairie’?

Skout has recovered well thanks to the very fortunate access we have to preventative penicillin injections that he now has in hospital every 28 days for the next ten years. Skout has a team of doctors guiding us in his health and healing and the best news of all is that 12 months on from diagnosis and a year of monthly injections, Skout’s heart has returned to being a strong and very brave heart.

Thanks to Skout and his mother Hayley for sharing their story, and to Vicki Wade for arranging its inclusion in this report.

Noonan S (2020) 'Prevention of ARF and RHD - in detail', RHD Australia website, viewed 27 February 2024.

RHDAustralia (ARF/RHD writing group) (2020) 'The 2020 Australian guideline for the prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease', 3.2 edn (2022), RHDAustralia, Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin.

Sims SA, Colquhoun S, Wyber R & Carapetis JR (2016) 'Global disease burden of group A streptococcus', in: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA (eds) Streptococcus pyogenes: basic biology to clinical manifestations, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Centre, Oklahoma City USA.

Webb RH, Grant C & Harnden A (2015) 'Acute rheumatic fever', British Medical Journal, 351(8017), doi:10.1136/bmj.h3443.

Wyber R & Carapetis J (2015) 'Evolution, evidence and effect of secondary prophylaxis against rheumatic fever', Journal of Practice of Cardiovascular Sciences, 1(1) 9–14, doi:10.4103/2395-5414.157554.

Wyber R, Noonan K, Halkon C, Enkel S, Ralph A, Bowen A, Cannon J, Haynes E, Mitchell A, Bessarab D, Katzenellenbogen J, Seth R, Bond-Smith D, Currie B, McAullay D, D'Antoine H, Steer A, de Klerk N, Krause V, Snelling T, Trust S, Slade R, Colquhoun S, Reid C, Brown A, Carapetis J (2020), 'The RHD Endgame Strategy: The blueprint to eliminate rheumatic heart disease in Australia by 2031', The END RHD Centre of Research Excellence, Telethon Kids Institute, accessed 21 February 2024.