Short-term or emergency accommodation

For the purposes of the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC), short-term or emergency accommodation includes refuges, crisis shelters, couch surfing (in this case examined separately), living temporarily with friends or relatives, insecure accommodation on a short-term basis, emergency accommodation arranged by a specialist homelessness agency (for example, in hotels and motels, bed and breakfast), boarding or rooming house, or transitional housing [1].

Who is in short-term or emergency accommodation?

Between 2011–12 and 2014–15, a total of 47,501 clients, (11% of all Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) clients aged 15 years and over) were in short-term or emergency accommodation upon first presentation to SHS. Per year, this ranged from 19,487 in 2011–12 to 16,978 in 2014–15.

Typically those in short-term or emergency accommodation are…

female, aged less than 35 years, unemployed and located in Major cities.

Overview of cohort characteristics

| Characteristic | Short-term or emergency accommodation | SHSC population |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 53% | 61% |

| Aged 15–35 years | 56% | 54% |

| Indigenous | 18% | 16% |

| employed | 8% | 13% |

| Lived in a Major city | 69% | 64% |

| Presented alone | 48% | 36% |

| Reported having experienced domestic and family violence | 32% | 35% |

| Reported a mental health issue | 38% | 28% |

| Diagnosed with a mental health issue | 49% | 22% |

| Had an issue with drugs or substance abuse | 19% | 12% |

Additionally:

- Just over half (53%) of those in short-term or emergency accommodation were female. While the proportions have remained consistent across financial years, the total number of clients have decreased.

- More than half (56%) were aged 15 to 35 years; almost 1 in 4 (23%) were aged 35–44 years, and 1 in 5 (22%) were aged 45 years and over. This is in line with the general SHS population with just over half (54%) aged 15 to 35 years.

- Indigenous Australians were over-represented in both the short-term or emergency accommodation cohort (18%) and general SHS population (16%) compared with the general Australian population (3%).

- Less than 1 in 10 (8%) were employed.

- Almost 7 in 10 (69%) of those in short-term or emergency accommodation were located in a Major City, which is higher than the comparable SHS client population (64%). A further 28% were located in Inner- or Outer Regional areas.

- Almost half (48%) presented to SHS agencies alone, while 3 in 10 (30%) presented with at least one child. Almost twice as many males presented alone (around 62% compared with around 35%); more than three times as many females presented with one or more children (around 44% compared with around 13%).

- Almost 1 in 3 (32%) reported experiencing domestic and family violence. Just over half (51%) of females reported experiencing domestic and family violence compared with around 11% of males.

- Almost 2 in 5 (38%) reported a current mental health issue; while almost half (49%) reported a diagnosed mental health issue (both slightly higher for males than for females).

- Almost 1 in 5 (19%) reported ever having an issue with drugs or substance abuse: higher for males than for females (26% compared with 14%).

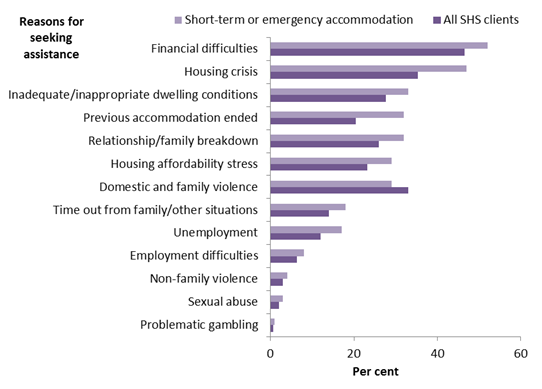

Reasons for seeking assistance

The most common reasons people in short-term or emergency accommodation sought assistance from SHS were (Figure ST.1):

- accommodation issues: including housing crisis (47%), inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (33%), or prior accommodation ending (32%)

- financial reasons: including financial difficulties (52%), housing affordability stress (29%), unemployment (17%), employment difficulties (8%) or problematic gambling (1%)

- interpersonal relationships: including relationship/family breakdown (32%), domestic and family violence (29%), time out from family/other situation (18%), non-family violence (4%), and sexual abuse (3%, the highest of all three cohorts).

Figure ST.1: Reasons for seeking assistance, short-term or emergency accommodation residents and all SHS clients, 2011–2015 (per cent)

Source: Supplementary data source table.

Clients in short-term or emergency accommodation were more likely to seek assistance from SHS for accommodation or financial issues than health related issues, but they were still more likely than the SHS client population to seek assistance for health related issues (33% compared with 25%). This was most pronounced for:

- mental health issues (21% compared with 15% of SHS clients), and

- problematic drug or substance use (11% compared with 7% of SHS clients).

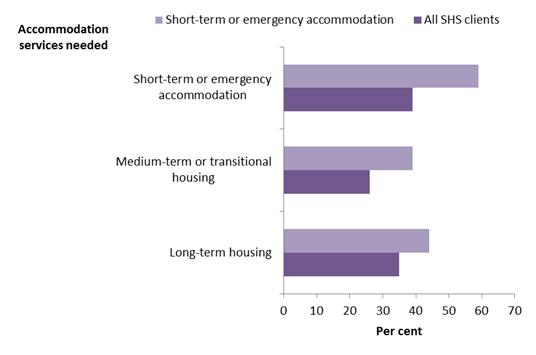

What services do those in short-term or emergency accommodation need and what services are provided?

Clients in short-term or emergency accommodation are more likely to need accommodation services

At the time of presentation to SHS, more than three-quarters (78%) of clients in short-term or emergency accommodation needed assistance with accommodation, compared with just over half (55%) of all SHS clients (Supplementary data tables ST.12; SHS.1). This need was highest for short-term or emergency accommodation and lowest for medium-term or transitional housing (Figure ST.2).

Figure ST.2: Accommodation services needed, short-term or emergency accommodation residents and all SHS clients, 2011–2015 (per cent)

Source: Supplementary data source table.

In general, short-term or emergency accommodation residents were more likely to receive assistance with accommodation when compared with all SHS clients (72% compared with 57%, respectively).

Those in short-term or emergency accommodation were more likely than SHS clients to receive all forms of accommodation:

- short-term or emergency accommodation (75% compared with 65%)

- medium-term/transitional housing (42% compared with 30%), or

- long-term housing (11% compared with 8%).

Those in short-term or emergency accommodation are also more likely than SHS clients to need assistance with general services such as:

- material aid/brokerage (51% compared with 39% of SHS clients)

- transport (39% compared with 23% of SHS clients)

- meals (38% compared with 23% of SHS clients)

- laundry/shower facilities (34% compared with 19% of SHS clients)

Clients in short-term or emergency accommodation are less likely to need assistance with domestic and family violence

Clients in short-term or emergency accommodation were less likely to request assistance for domestic and family violence (22%) compared with all SHS clients (27%), but a similar proportion required assistance with interpersonal relationships (52% and 53%, respectively).

Housing pathways for clients in short-term or emergency accommodation

Just over 1 in 10 (12%) of those in short-term or emergency accommodation experienced repeat homelessness between 2011–12 and 2014–15. This means that a client had transitioned between being homeless, housed and then homeless again at least once during this time.

Females in short-term or emergency accommodation were marginally more likely then males to transition between being homeless and being housed between 2011 and 2015. Over the same period, the number of males who present to homelessness services for assistance while in short-term or emergency accommodation who have experienced more than one episode of homelessness increased, but the number of females decreased.

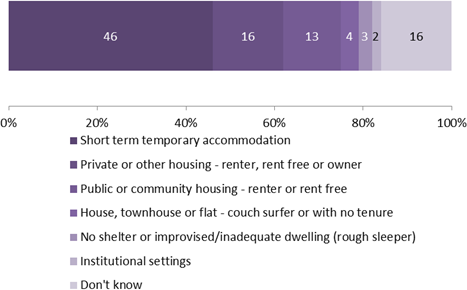

What are the housing outcomes for those in short-term or emergency accommodation?

Almost half (46% or 21,980) of clients who first presented to homelessness services already in short-term or emergency accommodation remained in short-term or emergency accommodation at the end of support. Almost 1 in 3 (29%) clients presenting to SHS in short-term or emergency accommodation ended their support 'housed' (16% ended their support in private rental housing and 13% in public or community housing).

Other housing outcomes for those in short-term or emergency accommodation who sought assistance from SHS agencies included: couch surfing (4%), rough sleeping (3%), and ending support in an institutional setting (2%). Despite support periods being closed, the housing outcome for almost 1 in 5 (16%) clients in short-term or emergency accommodation was unknown at the end of their support (Figure ST.3).

Figure ST.3: Housing outcomes, short-term or emergency accommodation residents, 2011–2015 (per cent)

Source: Supplementary data source tables.

Compared with the total short-term or emergency accommodation population, those that ended their support 'housed' were more likely to: be female, have experienced domestic or family violence, have reported experiencing and been diagnosed with a mental health issue and presented to services accompanied by children (Table ST.2).

| Characteristic | 'Housed' short-term or emergency accommodation residents | Total short-term or emergency accommodation population |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 64% | 53% |

| Reported having experienced domestic or family violence | 42% | 32% |

| Reported a mental health issue diagnosed with a mental health issue |

43% 49% |

38% 37% |

| Presented with one or more children | 41% | 30% |

| Have a drug or alcohol issue | 18% | 25% |

| Experience repeated episodes of homelessness | 14% | 20% |

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2013. Specialist Homelessness Services Collection manual. Cat. No. HOU 268. Canberra: AIHW.