Clients who have experienced family and domestic violence

In Australia, 1 in 6 women (17% or 1.6 million) and 1 in 16 men (6% or 548,000) have experienced physical or sexual violence from a current or previous cohabiting partner since the age of 15 (ABS 2017). Approximately 2.5 million Australian adults (13%) experienced abuse during their childhood; the majority knew the perpetrator and experienced multiple incidents of abuse (ABS 2017). Family and domestic violence affects people of all ages and from all backgrounds, but it predominantly affects women and children (AIHW 2019).

Family and domestic violence is the main reason women and children leave their homes in Australia (FaHCSIA 2008). Specialist Homelessness Service (SHS) agencies provide the principal crisis response for these people (Flanagan et al. 2019), with clients who have experienced family and domestic violence making up 40% of SHS clients (see Clients, services and outcomes). Women and children affected by family and domestic violence are a national priority cohort in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, which came into effect on 1 July 2018 (CFFR 2019) (see Policy section for more information). Effective services are required that recognise the impact of trauma and violence and the need for support in a safe and respectful environment (Flinders 2008). To achieve long term housing stability, SHS responses often need to encompass a broad range of interventions and integrate services and supports (Flanagan et al. 2019).

Key findings

- In 2018–19, 116,400 SHS clients had experienced family and domestic violence, equating to 40% of all clients.

- Females made up the majority (90%) of adult (aged 18 years and over) SHS clients having experienced family and domestic violence.

- Half (50%) of all younger SHS clients (aged under 18) had experienced family and domestic violence.

- More SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence were at risk of homelessness (63%) upon presentation to an SHS agency, than were homeless (37%).

- On average, each client who experienced family and domestic violence received assistance twice from homelessness agencies over the 12 month period (2 support periods per client), and a median of 54 days of support.

- The largest change to housing situation at the end of service provision was for clients in public or community housing—increasing from 16% of clients at the start of support to 22% at the end of support.

Data quality statement note:

From 2017–18 to 2018–19, there was a three per cent decrease in the total number of Victorian homelessness clients and a 10 per cent decrease in family violence clients following years of steady increases in these numbers. The decrease was primarily due to a practice correction in how some family violence agencies were recording clients. In addition, during 2018–19, a phased process to shift family violence intake to non-SHS services began, which may result in an overall decrease in the number of SHS family violence clients over the coming years. Caution should be used when comparing Victorian client numbers over recent years. For more information, see 2018–19 SHS Data Quality Statement.

Reporting clients experiencing family and domestic violence in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

In the SHSC, a client is reported as experiencing family and domestic violence if in any support period during the reporting period the client sought assistance as a result of physical or emotional abuse inflicted on the client by a family member or if as part of any support period a person required family or domestic violence assistance.

The SHSC reports on clients experiencing family and domestic violence of any age. It also reports on both victims and perpetrators who may be assisted by SHS agencies. Currently, the SHSC cannot separately identify these groups, but changes to family and domestic violence service provision are in place for the 2019–20 reporting period. For more information, see Technical notes.

Client characteristics

In 2018–19 (Table FDV.1):

- SHS agencies assisted around 116,400 clients (of any age) who experienced family and domestic violence. This equates to 40% of the 290,300 SHS clients in 2018–19.

- There were around 4,700 fewer SHS clients seeking assistance for family and domestic violence compared with 2017–18. This is in contrast to steady increases in numbers over recent reporting periods (on average 6% each year since 2014–15). See data quality statement for further information.

- The rate of SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence was 46.6 per 10,000 population, decreasing from 49.2 in 2017–18.

| 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of clients | 92,349 | 105,619 | 114,757 | 121,116 | 116,419 |

| Proportion of all clients | 36 | 38 | 40 | 42 | 40 |

| Rate (per 10,000 population) | 39.3 | 44.3 | 47.4 | 49.2 | 46.6 |

Housing situation at the beginning of the first support period (proportion (per cent) of all clients) | |||||

Homeless | 37 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 37 |

At risk of homelessness | 63 | 62 | 61 | 61 | 63 |

| Length of support (median number of days) | 40 | 38 | 39 | 43 | 54 |

| Average number of support periods per client | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Proportion receiving accommodation | 41 | 39 | 37 | 35 | 36 |

| Median number of nights accommodated | 32 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 |

| Proportion of a client group with a case management plan | 64 | 64 | 64 | 65 | 69 |

| Achievement of all case management goals (per cent) | 22 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 19 |

Notes

- Rates are crude rates based on the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) at 30 June of the reference year. Minor adjustments in rates may occur between publications reflecting revision of the estimated resident population by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- The denominator for the proportion receiving accommodation is all SHS clients who have experienced family and domestic violence. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

- The denominator for the proportion achieving all case management goals is the number of client groups with a case management plan. Denominator values for proportions are provided in the relevant supplementary table.

- Data for 2014–15 to 2016–17 have been adjusted for non-response. Due to improvements in the rates of agency participation and SLK validity, data from 2017–18 are not weighted. The removal of weighting does not constitute a break in time series and weighted data from 2014–15 to 2016–17 are comparable with unweighted data for 2017–18 onwards. For further information, please refer to the Technical Notes.

- From 2017–18 to 2018–19, there was a three per cent decrease in the total number of Victorian homelessness clients and a 10 percent decrease in family violence clients following years of steady increases in these numbers. The decrease was primarily due to a practice correction in how some family violence agencies were recording clients. In addition, during 2018–19, a phased process to shift family violence intake to non-SHS services began, which may result in an overall decrease in the number of SHS family violence clients over the coming years. Caution should be used when comparing Victorian client numbers over recent years.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2014–15 to 2018–19.

Age and sex

In 2018–19, of all clients who experienced family and domestic violence:

- Clients had a younger age profile than all SHS clients, with over 1 in 3 (37%) aged less than 18 years; 1 in 3 (32%) aged 18 to 34, and a further 1 in 3 (31%) aged 35 and over (Supplementary table FDV.1).

- Half (50%) of all SHS clients aged less than 18 had experienced family and domestic violence (Supplementary tables FDV.1 and CLIENTS.1).

- 9 in 10 (90%) adult SHS clients (aged 18 years and over) who experienced family and domestic violence were female.

- There was very little difference in the number and proportion of males (18,000 or 50%) and females (18,300 or 50%) aged under 15 experiencing family and domestic violence, but from age 15, the majority of clients experiencing family and domestic violence were female (89%, 11% male).

Children experiencing family and domestic violence may seek SHS support with their family, or independently if fleeing the home. For children in particular, SHS support is critical to reduce the likelihood of a long term experience/risk of homelessness (Kaleveld et al 2018).

Indigenous clients

In 2018–19, of all clients who experienced family and domestic violence, around 68,900 clients) (Supplementary table FDV.8):

- 2 in 5 (40% or more than 27,200 clients) had experienced family and domestic violence.

- 3 in 10 (29%) Indigenous clients experiencing family and domestic violence were less than 10 years of age.

State and territory and remoteness

- Victoria recorded the highest number of SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence (50,800), representing almost half (44%) of this client group in Australia (Supplementary table FDV.2).

- New South Wales had the second highest number of clients who experienced family and domestic violence at 27,900 (24% of clients or 35 per 10,000 population). NSW was 1 of 3 states reporting an increase in numbers of clients experiencing family and domestic violence; an increase of 1,200 clients since 2017–18.

- While recording one of the lowest counts (4,700 clients or 4%) of family and domestic violence clients in Australia, the Northern Territory had the highest rate of clients, at 188 clients per 10,000 population.

- Almost 2 in 3 (63%, or 73,400 clients) SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence accessed services in Major cities, with a further 22% in Inner regional and 10% in Outer regional areas (Supplementary table FDV.10).

Living arrangements

In 2018–19, of the 103,300 children and adult clients who experienced family and domestic violence and stated their living arrangement at the beginning of SHS support (Supplementary table FDV.9)

- nearly half (49% or 50,700 clients) were living as single parents with one or more children

- 1 in 5 (19% or 19,500 clients) were living alone

- almost 12,600 people (12%) were living with other family, which can mean a person with or without children living (as a couch surfing arrangement) with others.

This was similar to 2017–18, albeit with fewer clients not stating their living arrangement at the beginning of support (down from 22,900 to 13,100 clients in 2018–19).

New or returning clients

Clients who have been victims of family and domestic violence may cycle in and out of homelessness due to lack of financial security and stable housing options and may return to the perpetrator on numerous occasions (DFHCSIA 2008). In 2018–19 (Supplementary table FDV.7):

- Of the 116,400 SHS clients (of all ages) who experienced family and domestic violence, 45% were new to the SHS and 55% were returning clients, that is, had previously been assisted by a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in 2011–12.

- Of the new clients, 45% (23,400 clients) were aged under 18, 50% were aged 18–55, and 5% were aged 55 and over.

- By contrast, of the returning clients, fewer (19,300 clients or 30%) were under 18.

Selected vulnerabilities

People who experience family and domestic violence may experience other vulnerabilities such as a current mental health issue and/or problematic drug and/or alcohol use. In 2018–19, of the 89,100 clients aged 10 and over who experienced family and domestic violence (Table FDV.2):

- almost 6 in 10 (58% or 52,000 clients) did not report experiencing an additional vulnerability

- 3 in 10 clients (30% or 26,300 clients) also reported a current mental health issue

- around 1 in 10 clients (9% or 8,400 clients) reported 3 key vulnerabilities (family and domestic violence, current mental health issues and problematic drug and/or alcohol use).

Four in 10 clients (42% or 37,100 clients) who experienced family and domestic violence reported experiencing at least 1 additional vulnerability (either a current mental health issue and/or problematic drug and/or alcohol use).

- The experience of family and domestic violence was more likely to be reported with a current mental health issue (34,600 clients) than problematic drug and/or alcohol use (10,800 clients).

Family and domestic violence | Mental health issue | Problematic drug and/ | Clients | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Yes | Yes | Yes | 8,351 | 9.4 |

Yes | Yes | No | 26,279 | 29.5 |

Yes | No | Yes | 2,455 | 2.8 |

Yes | No | No | 52,041 | 58.4 |

|

|

| 89,126 | 100.0 |

Notes

- Clients are assigned to one category only based on their vulnerability profile.

- Clients are aged 10 an over

- Totals may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2018–19.

Service use patterns

In 2018–19 (Table FDV.1):

- Clients who experienced family and domestic violence had a median of 54 days and 30 nights of support and an average of 2.0 support periods per client.

- Many (69%) SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence had a case management plan, up from 65% in 2017–18. Around 1 in 5 (19%) of those with a plan achieved all the set goals.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2018–19, of those SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence:

- 7 in 10 clients (69%) identified family and domestic violence as the main reason for accessing SHS services, while a further 9% identified housing crisis (Supplementary table FDV.5).

- For those clients presenting at risk of homelessness, the most common main reasons for seeking assistance were (Supplementary table FDV.6):

- family and domestic violence (75%)

- housing crisis (6%)

- financial difficulties (4%).

- For those clients presenting as homeless, the most common main reasons for seeking assistance were:

- family and domestic violence (53%)

- housing crisis (16%)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (9%).

Services needed and provided

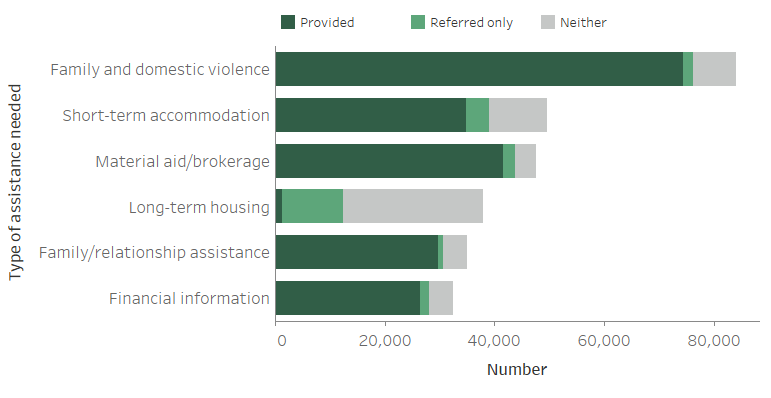

In 2018–19, 84,000 (72%) SHS clients who experienced family and domestic violence needed specific assistance for this reason, including therapeutic discussion or group sessions, counselling and specialised support services. Of those identified as needing assistance for family and domestic violence, 89% were provided assistance (Figure FDV.1).

The next most common services requested by this client group were:

- short-term or emergency accommodation (43% or over 49,700), with 70% of those needing this service, receiving this service

- material aid/brokerage (41% or over 47,500), with 88% of those needing this service receiving this service

- long-term housing (33% or over 37,800), with 3% of those needing this service receiving this service and a further 30% referred.

Figure FDV.1: Clients who have experienced family and domestic violence, by need for services and assistance and service provision status (top 6), 2018–19

Notes

- Excludes ‘Other basic assistance’, ‘Advice/information’ and ‘Advocacy/liaison on behalf of client’.

- 'Short-term accommodation' includes temporary and emergency accommodation.

- 'Neither' indicates a service was neither provided nor referred.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2018–19, Supplementary table FDV.3.

Outcomes at the end of support

Outcomes presented here describe the change in clients’ housing situation between the start and end of support. Data is limited to clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year—meaning that their support periods had closed and they did not have ongoing support at the end of the year.

Many clients had long periods of support or even multiple support periods during 2018–19. They may have had a number of changes in their housing situation over the course of their support. These changes within the year are not reflected in the data presented here, rather the client situation at the start of their first support period in 2018–19 is compared with the end of their last support period in 2018–19. A proportion of these clients may have sought assistance prior to 2018–19, and may again in the future.

At the end of the reporting period in 2018–19 (Table FDV.3):

- Just over 6 in 10 clients experiencing family and domestic violence presented to agencies known to be housed (61% or 40,100 clients), and by the end of support this had risen to over 7 in 10 (72% or 46,900). Much of the increase can be attributed to more clients living in public or community housing, up from 16% to 22% by the end of support.

- The most common housing situation for clients experiencing family and domestic violence at both the start and end of SHS support was private or other housing; 28,800 clients (44%) at the start, and 31,700 (48%) at the end of SHS support.

- At the end of support, almost 3 in 10 clients experiencing family and domestic violence were known to be experiencing homelessness (28% or 18,600 clients). Compared with the start of support, there were 7,500 fewer clients experiencing homelessness; down from 26,100 clients (39%).

- Clients experiencing family and domestic violence known to be homeless were more likely to present to agencies while living in short term temporary accommodation (20% or 13,200 clients). This was the most common housing situation for those experiencing homelessness, and remained so at the end of support (16% or 10,200 clients living in short term temporary accommodation).

These findings demonstrate that by the end of support, there was a reduction in homeless housing circumstances and an increase in other, potentially more positive, housing solutions. That is, more clients ended support in public or community housing (renter or rent-free) or private or other housing (renter or rent-free) compared with the start of support.

Housing situation | Beginning of support | End of | Beginning of support | End of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

No shelter or improvised/inadequate dwelling | 3,569 | 1,984 | 5.4 | 3.0 |

| Short term temporary accommodation | 13,217 | 10,154 | 20.0 | 15.5 |

House, townhouse or flat - couch surfer or with no tenure | 9,276 | 6,447 | 14.0 | 9.8 |

| Total homeless | 26,062 | 18,585 | 39.4 | 28.4 |

Public or community housing - renter or rent free | 10,356 | 14,501 | 15.6 | 22.1 |

Private or other housing - renter, rent free or owner | 28,765 | 31,720 | 43.5 | 48.4 |

Institutional settings | 998 | 682 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

Total at risk | 40,119 | 46,903 | 60.6 | 71.6 |

| Total clients with known housing situation | 66,181 | 65,488 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Not stated/other | 21,402 | 22,095 | ||

Total clients | 87,583 | 87,583 |

|

|

Notes

- Percentages have been calculated using total number of clients as the denominator (less not stated/other).

- It is important to note that individual clients beginning support in one housing type need not necessarily be the same individuals ending support in that housing type.

- Not stated/other includes those clients whose housing situation at either the beginning or end of support was unknown.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection. Supplementary table FDV.4.

Housing outcomes for homeless versus at risk clients

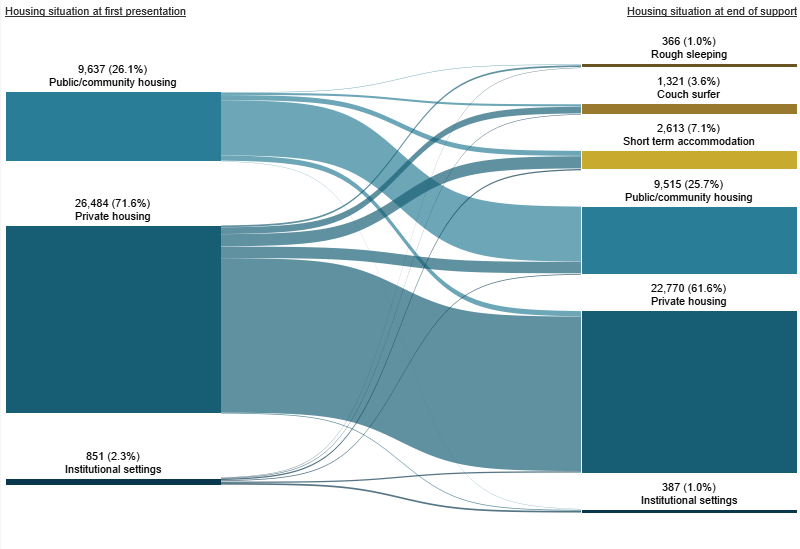

For clients with a known housing status who were at risk of homelessness at the start of support (almost 37,000 clients), by the end of support (Figure FDV.2):

- Most (22,800 clients or 62%) were in private housing.

- Around 9,500 clients (26%) were in public housing.

A smaller number were experiencing homelessness at the end of support (around 4,300 clients or 12% of those who started support at risk).

Figure FDV.2: Housing situation for clients with closed support who began support at risk of homelessness, 2018–19

Notes

- Excludes clients with unknown housing situation

- Includes only those clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year (meaning that their support period(s) had closed and they were not in ongoing support at the end of the year).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, 2018–19

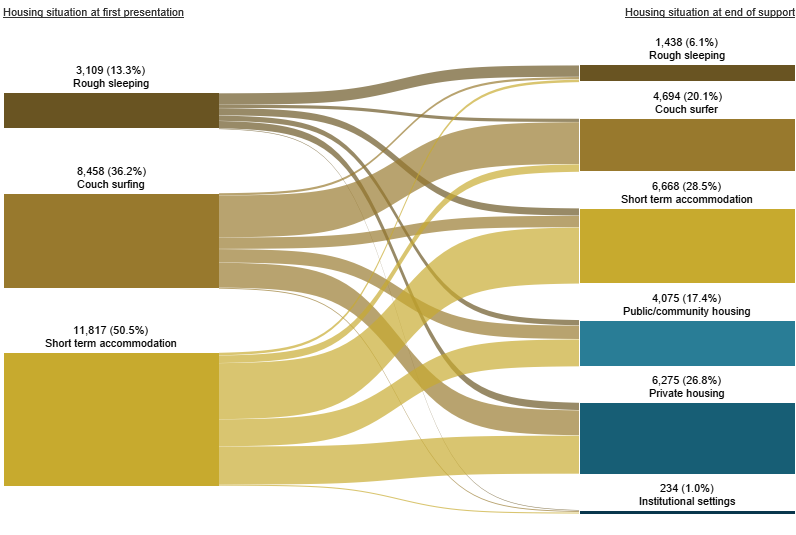

For clients who were known to be homeless at the start of support (just over 23,400 clients), agencies were able to assist (Figure FDV.3):

- 6,700 clients (29%) into short term accommodation

- 6,300 (27%) into private housing.

A further 4,700 clients (20%) were couch surfing at the end of support.

Figure FDV.3: Housing situation for clients with closed support who were experiencing homelessness at the start of support, 2018–19

Notes

- Excludes clients with unknown housing situation

- Includes only those clients who ceased receiving support during the financial year (meaning that their support period(s) had closed and they were not in ongoing support at the end of the year).

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection, 2018–19

Clients accessing SHS agencies who have experienced family and domestic violence have some notable differences from other client groups. Compared with other client groups, more clients who experienced family and domestic violence were in private housing at the start and end of SHS support. Perhaps driven by their greater likelihood of presenting while housed, their service use patterns were considerably less than other client groups and they were less likely to need accommodation overall. Short-term accommodation was their greatest housing need which is in contrast to other groups which often needed long-term housing the most. This client group were more likely to be new, rather than returning clients, and more likely to experience only one selected vulnerability (family and domestic violence).

It is important to note that this analysis is based on the 116,400 clients of SHS agencies in 2018–19. While there are various support services available, many people do not seek advice or support after incidents of family or domestic violence. Other research suggests that for those who experienced physical and/or sexual violence from a current cohabiting partner, 1 in 2 women never sought advice or support (AIHW 2019).

People fleeing violence often require safe, affordable, independent housing in which to live in the long term and yet, some are unable to secure it (Flanagan 2019). In the absence of an appropriate housing solution, some people may consider returning to a violent relationship (Flanagan 2019). While the availability of long-term housing is a key challenge for SHS clients overall, it is particularly so for this large client group.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2017. Personal Safety, Australia, 2016. ABS cat. no. 4906.0 Canberra: ABS.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019. Cat. no: FDV 2 Canberra: AIHW.

CFFR (Council on Federal Financial Relations) National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. 2018. Viewed 18 September 2019.

FaHCSIA (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs) 2008. The Road Home A national approach to Reducing homelessness Canberra: FaHCSIA.

Flanagan K, Blunden H, Valentine K & Henriette J 2019. Housing outcomes after domestic and family violence, AHURI Final Report 311, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne, doi: 10.18408/ahuri-4116101.

Flinders (Flinders University) Prepared for the Office for Women Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Tually S, Faulkner D, Cutler C and Slatter M 2008. Women, Domestic and Family Violence and Homelessness A Synthesis Report Viewed 19 September 2019 https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/women/publications-articles/reducing-violence/women-domestic-and-family-violence-and-homelessness-a-synthesis-report?HTML

Kaleveld L, Seivwright A, Box E, Callis Z & Flatau P 2018. Homelessness in Western Australia: A review of the research and statistical evidence. Perth: Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities. Viewed 27/06/2019.

Robinson C 2003. Understanding iterative homelessness: the case of people with mental disorders, AHURI.

Spinney A, 2012. Home and safe? Policy and practice innovations to prevent women and children who have experienced family and domestic violence from becoming homeless. Final report no. 196. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.