Suitability of dwelling size

On this page

Quick facts

- At 30 June 2020:

- the majority (79%) of social housing households were considered to be residing in dwellings that met the standard (adequate) to their household composition.

- 4% of public housing, 25% of state owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH) and 4% of community housing households were considered to be in overcrowded dwellings.

- 17% of public housing and 27% of SOMIH housing households were considered to be in underutilised dwellings.

- Of public housing households, the highest number of overcrowded dwellings were in Major Cities (8,200 households).

- The number of overcrowded public housing dwellings dropped from 13,700 households in 2015 to 11,000 in 2020.

Ensuring the best fit between a social housing dwelling and household requirements is not a straightforward process. It is influenced by the availability of dwellings and dwelling configuration, as well as the age, condition and location of the property. This is in addition to the availability of options and specific household requirements (such as disability modifications), and the cost to relocate existing tenants, as well as their willingness to relocate.

The Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS) is a generally accepted standard by which the dwelling size requirements of a given household are measured in Australia. CNOS, however, is not necessarily used by all states/territories in the operation of social housing programs.

Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS)

A measure of the appropriateness of housing that is sensitive to both household size and composition, the CNOS specifies that:

- no more than 2 people shall share a bedroom

- parents or couples may share a bedroom

- children under 5 years, either of the same sex or opposite sex, may share a bedroom

- children under 18 years of the same sex may share a bedroom

- a child aged 5–17 should not share a bedroom with a child under 5 of the opposite sex

- single adults 18 years and over, and any unpaired children require a separate bedroom.

Source: Statistics Canada 2019

For more information on the CNOS, see AIHW Metadata Online Registry (METeOR).

Whilst the CNOS is a useful guide to estimate the proportion of dwellings that may be underutilised or overcrowded, there are some cases where a dwelling may not match a household size for good reason. For example, where custody of children is shared; where tenants may have live-in care arrangements; or to take into consideration future needs of children who may need separate bedrooms in years to come.

CNOS also does not take into consideration cultural norms, with some studies suggesting that, the approach is particularly problematic for Aboriginal and Torres Strait households (Memmott et al 2003; Memmott et al 2011; Pholeros 2010). Regardless of the appropriateness of the measure, overcrowding based on CNOS has been found to adversely affect the physical and mental health of residents (AIHW 2014; Booth & Carroll 2005; SCRGSP 2016).

Housing suitability

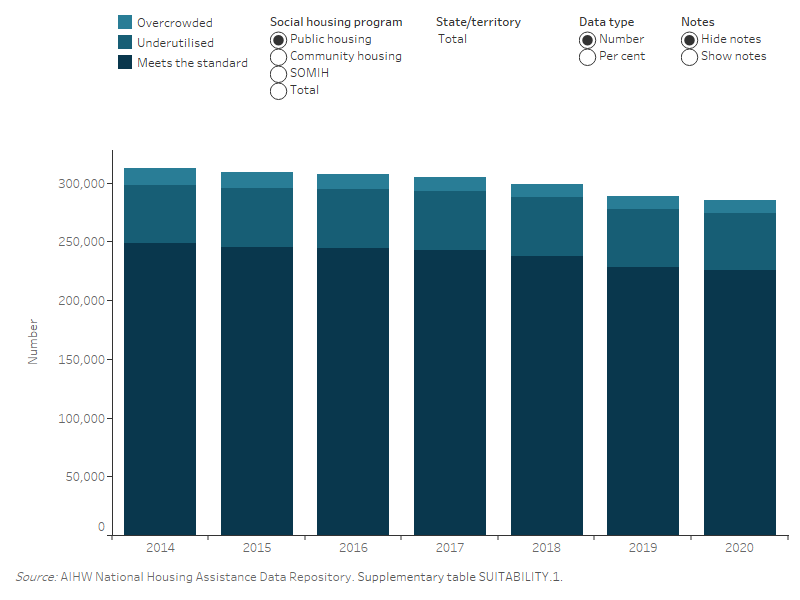

At 30 June 2020, the vast majority of social housing households were living in dwellings that met the required occupancy standard. There were more social housing households living in underutilised dwellings (61,000 or 15%) than in overcrowded dwellings (18,500 or 5%) (Figure SUITABILITY.1) (Supplementary table SUITABILTY.1).

SUITABILITY.1: Households, by suitability of dwelling size and social housing program, at 30 June 2014 to 2020

Figure SUITABILITY.1: Households, by suitability of dwelling size and social housing program, at 30 June 2019. This horizontal stacked bar graph shows the vast majority of social housing households were living in dwellings that were adequate (80%); there were more social housing households living in underutilised dwellings (16%) than in overcrowded dwellings (5%), in 2019. The majority of households in the public housing (79%) and community housing (85%) were considered to be residing in dwellings adequate to their household composition; compared with SOMIH where 49% of households were considered to be in residing in dwellings that were adequate. SOMIH had the highest proportion of underutilised dwellings (26%) and overcrowded dwellings (25%).

Key characteristics of households

Key characteristics on the suitability of social housing dwellings for households at 30 June 2020 were (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.4):

- in overcrowded households living in public housing, those aged 35–44 (31%) were the largest 10 year age group.

- most households in overcrowded SOMIH households comprised of group and mixed composition (79%).

- in underutilised SOMIH households, those aged 55–64 (30%) were the largest 10 year age group.

- most households in underutilised households in public housing comprised of Single adults (59%).

Overcrowding data for Indigenous community housing and community housing were not available.

Overcrowding

In simple terms, overcrowding occurs when the dwelling is too small for the size and composition of the household living in it. In Australia, a dwelling requiring at least 1 additional bedroom is designated as overcrowded, as defined by the CNOS standard described above.

At 30 June 2020, 11,000 (4%) public housing and 4,100 (4%) community housing households were in overcrowded dwellings. One in 4 (25% or 3,400 households) SOMIH households were in overcrowded dwellings (Figure SUITABILITY.1) (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.1).

Overcrowding data for Indigenous community housing are not available.

The proportion of overcrowded households in public housing has remained stable at around 4–5% between 2014 and 2020. Overcrowding in community housing has remained at around 4% over the same time period, during a period of considerable growth in overall stock levels (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.1). See Social housing dwellings section for further information.

Nationally, the proportion of overcrowded households in SOMIH decreased from 10% in 2014 to 9% in 2016. The addition of over 5,000 remote public housing dwellings in the Northern Territory to the SOMIH data collection from 2017 increased the overcrowding counts and proportions. This is reflected in the most recent data, which show that overcrowding levels for SOMIH in Australia have been stable for the last four reporting periods, at around one-quarter (24–25%) of SOMIH households (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.1).

Location

The proportion of households in overcrowded dwellings varied across social housing programs, states and territories and remoteness areas. At 30 June 2020 (Figure SUITABILITY.1) (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.1 and 2):

- the Northern Territory had the highest proportion of public housing (8%) and SOMIH (54%) households in overcrowded dwellings.

- Tasmania had the highest proportion of households in overcrowded community housing dwellings (7%).

- of the public housing households, most households living in overcrowded dwellings were in Major Cities (8,200 households).

- for SOMIH, the greatest number of households living in overcrowded dwellings were in Very remote areas (2,100).

Overcrowding data for remoteness were not available for community housing and Indigenous community housing.

Overcrowding in Indigenous households

At 30 June 2020, there were 2,800 overcrowded Indigenous households living in public housing, representing almost 1 in 12 (8%) total Indigenous public housing households (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.2).

Underutilisation

A dwelling is said to be underutilised when it consists of 2 or more bedrooms surplus to the household requirements as determined by the CNOS measure.

Underutilisation can arise as a household ages and children leave the family home. Interpretation of underutilisation data needs to consider the circumstances of tenants. For example, tenants may have been living in a home for a number of years and their economic, social and community life is centred around that location. There may be no suitable location based alternatives when household composition changes. Underutilisation may also occur due to the housing stock being dominated by family-sized homes with 3 or more bedrooms (see Social housing dwellings) which may not be consistent with the overall social housing household composition profile (such as single adult households, see Occupants and households).

At 30 June 2020, 17% of public housing and 11% of community housing households were in underutilised dwellings. Social housing targeted towards Indigenous households had the highest proportion of underutilisation with 27% of SOMIH households living in underutilised dwellings. However, underutilisation data were not available for the Northern Territory for SOMIH or community housing (Figure SUITABILITY.1) (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.1).

Changes over time

Public housing underutilisation has remained steady between 2014 and 2020, at around 16–17%, while there has been some variation for community housing and SOMIH households. Underutilisation for households in SOMIH dwellings increased in recent years from around 23% in 2014 to 27% in 2020 (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.3). For community housing, rates of underutilisation have been variable over these years fluctuating between 9–12% (Figure SUITABILITY.1) (Supplementary table SUITABILITY.1).

Location

The proportion of households in underutilised dwellings varied by state and territory and remoteness area among the social housing programs. Key results at 30 June 2020 include (Figures SUITABILITY.1) (Supplementary tables SUITABILITY.1 and 3):

- For public housing, South Australia (26%) had the highest proportion of households in underutilised dwellings compared with the Northern Territory (8%) which had the lowest, consistent with previous years.

- Of the available SOMIH household data, around 1 in 3 households in South Australia (32%) and New South Wales (31%) were living in underutilised dwellings.

- For community housing, 21% of households in South Australia were reported as living in underutilised dwellings, which has been relatively consistent since 2016 (22%).

- Of the public housing households, those in Outer regional areas (21%) were most likely to be living in underutilised dwellings, with households in Remote areas (15%) being least likely. This is consistent with data from recent years.

- For SOMIH, the proportion of underutilised households ranged from 20% in Very remote areas to 30% in Major cities.

Glossary

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2014. Housing circumstances of Indigenous households: tenure and overcrowding. Cat no. IHW 132. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2019. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a focus report on housing and homelessness. Cat. no. HOU 301. Canberra: AIHW.

- Booth A & Carroll N 2005. Overcrowding and Indigenous Health in Australia. Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper no. 498. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University.

- Memmott P, Birdsall-Jones C, Go-Sam C, Greenop K & Corunna V 2011. Modelling crowding in Aboriginal Australia. AHURI Positioning Paper No.141. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Memmott P, Long S & Chambers C 2003. Categories of Indigenous ‘homeless’ people and good practice responses to their needs. AHURI Positioning Paper No. 53. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Pholeros P 2010. Will the Crowding Be Over or Will There Still Be Overcrowding in Indigenous Housing?: Lessons from the Housing for Health Projects 1985-2010 . Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, No. 27, Summer 2010: 8–18. Viewed 10 February 2021.

- SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2016. Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2016. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Statistics Canada 2019. Housing suitability of private household. Viewed 16 February 2021.