Mental health of prison entrants

Almost half of prison entrants (49%) reported having been told by a health professional that they have a mental health disorder, and more than 1 in 4 (27%) reported currently being on medication for a mental health disorder.

Reporting a history of mental health problems was more common among female (62%) than male entrants (47%). Consistent with this, a higher proportion of females than males were currently on medication for a mental health disorder (37% and 25%, respectively).

Eighteen percent of the youngest prison entrants (aged under 25) reported currently taking mental health related medication compared with at least 28% of older entrants (those aged 25 or over).

Non-Indigenous prison entrants were more likely than Indigenous prison entrants to have ever been told that they have a mental health disorder (51% and 44%, respectively), but the proportions taking mental health related medication was the same.

Psychological distress

Although almost half (49%) of all prison entrants experienced low levels of psychological distress during the four weeks immediately preceding entry to prison, almost 1 in 3 (31%) had high or very high levels of distress:

- The issues causing 'a lot' of distress for entrants were family or relationships in the community (34%), their current imprisonment (19%), and alcohol, tobacco and other drug issues (18%).

- Over 2 in 5 (45%) female entrants compared with 29% of male entrants experienced high or very high levels of distress.

- Over half (51%) of male entrants experienced low levels of distress in the 4 weeks preceding prison entry, compared with 33% of female entrants.

Levels of psychological distress were generally lower among those who were about to leave prison (dischargees), with 19% experiencing high or very high levels:

- The issues causing 'a lot' of distress for dischargees were their upcoming release from prison (13%) and family and relationships in the community (13%).

- Female dischargees were almost three times more likely than male dischargees to report very high levels of distress (19% compared with 6%).

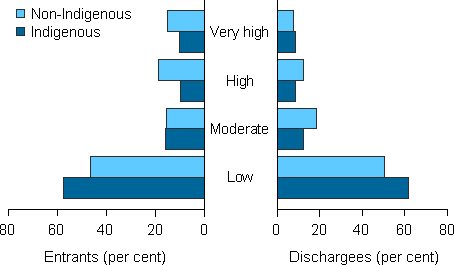

- reported psychological distress was lower for Indigenous than non-Indigenous prison entrants and dischargees (Figure 1). In the 4 weeks prior to incarceration, 1 in 5 (20%) Indigenous entrants experienced high or very high levels of distress, compared with 34% of non-Indigenous entrants.

Younger prison entrants experienced less distress than older entrants. About 1-in-5 (20%) of the youngest entrants (aged under 25) reported high or very high levels of distress, compared with 37% of those aged at least 35 years.

Figure 1: Prison entrants and dischargees, level of psychological distress, by Indigenous status, 2015

Note:

-

Excludes New South Wales as data were not provided for this indicator.

-

Levels of distress as indicated by scores on the K10: low (10–15), moderate (16–21), high (22–29) and very high (30–50).

Source: Entrant form and dischargee form, NPHDC 2015.

Changes to mental health while in prison

- Almost 1 in 5 (19%) prison dischargees, or 64% of those ever diagnosed with mental health condition, were offered treatment for a mental health condition while in prison.

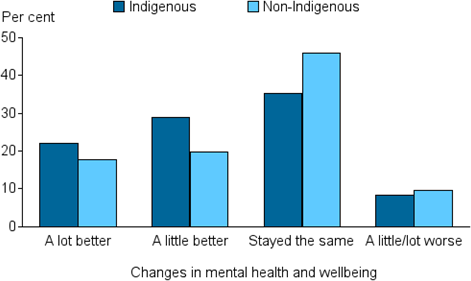

- More than 2 in 5 (41%) dischargees said their mental health had improved since being in prison, with 19% reporting that it had become a lot better, and a further 22% said it got a little better. Less than 1 in 10 (9%) dischargees reported that their mental health got a little or a lot worse.

- Male dischargees were less positive than women, with 10% of men reporting that their mental health had become a little or a lot worse since being in prison, compared with 4% of women.

- Indigenous dischargees were more positive than non-Indigenous dischargees—just over half (51%) of Indigenous dischargees reported that their mental health as either a lot better (22%) or a little better (29%) compared with 38% of non-Indigenous dischargees (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Prison dischargees' changes in mental health and wellbeing, by Indigenous status, 2015

Note: Excludes New South Wales as data were not provided for discharges.

Source: Dischargee form, NPHDC 2015.

Self assessed mental health

Over three quarters (78%) of dischargees, and two-thirds (67%) of entrants rated their mental health as being generally good or better:

- Men were more likely than women to assess their own mental health as being very good or excellent. Just over one-third (35%) of male entrants compared with 17% of female entrants gave this rating, as did 44% of male and 25% of female dischargees.

- Similarly, younger entrants and dischargees were more positive in their assessments of their own mental health than older prisoners. One-third (32–36%) of dischargees aged aged at least 35 gave a rating of very good or excellent, compared with 59% of the youngest dischargees aged 18–24 years.

Further information

See Chapter 4 of The health of Australia's prisoners 2015.