Health of people experiencing homelessness

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Health of people experiencing homelessness, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Health of people experiencing homelessness. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-experiencing-homelessness

MLA

Health of people experiencing homelessness. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 27 June 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-experiencing-homelessness

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health of people experiencing homelessness [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-experiencing-homelessness

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2024, Health of people experiencing homelessness, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-experiencing-homelessness

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

People experiencing homelessness and those at risk of homelessness (see glossary) are among Australia’s most socially and economically disadvantaged. Experiencing or being at risk of homelessness is associated with a higher risk of adverse health, social, and economic outcomes (Fitzpatrick et al. 2013).

Health problems can arise as a consequence of experiencing homelessness, including malnutrition and dental problems (Goode et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2022). Homelessness can expose people to violence and victimisation, result in long-term unemployment and lead to the development of chronic ill health (Larney et al. 2009). People experiencing homelessness have significantly higher rates of death and chronic illness when compared with the general population (Morrison 2009).

People experiencing health issues while also experiencing homelessness may have difficulties managing their health conditions which can lead to the development and/or exacerbation of a chronic health issue. This in turn can reduce a person’s ability to sustain wellbeing, employment, housing, and personal networks, further impacting their ability to sustain stable housing.

People experiencing homelessness

On Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census night in 2021, more than 122,000 people were estimated to be experiencing homelessness in Australia, up from 116,000 (an increase of 5.2%) since 2016. Of the people experiencing homelessness in 2021, 56% were male, 58% were younger than 35 and 20% identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) origin (ABS 2023).

Of people experiencing homelessness in Australia in 2021:

- 47,900 (39%) were living in 'severely' crowded dwellings

- 24,300 (20%) were in supported accommodation for the homeless

- 7,600 (6.2%) were living in improvised dwellings, tents or sleeping out (also termed rough sleeping) (ABS 2023).

The General Social Survey provides some insights into the health status of people who have experienced homelessness in Australia. In 2019, an estimated 2.2 million Australians aged 15 and over had been without a permanent place to live at some time in their lives (ABS 2019). Around 75% stayed with friends or relatives and 34% experienced rough sleeping. The most common reason for the most recent experience of being without a permanent place to live was a relationship or family breakdown (48%).

Government-funded Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) across Australia provide services supporting people who are experiencing homelessness or who are at imminent risk of homelessness. In 2022–23, SHS services provided support to around 274,000 clients. Of those, 116,000 (or 47%) clients were experiencing homelessness when they first began support (AIHW 2023).

For further information about the profile of people experiencing homelessness and the support provided by specialist homelessness services, see Homelessness and homelessness services.

The impact of homelessness on health

There is a growing volume of research on the impact of insecure housing on the health of individuals and the associated costs to the health system (Davies and Wood 2018; Zaretzky and Flatau 2013).

Meeting basic physical needs such as food, water and a place to sleep can be the most important day-to-day priority for people experiencing homelessness, especially those rough sleeping. Subsequently health needs are often not considered until an emergency arises (Wise and Phillips 2013). While rough sleeping is the least common form of homelessness in Australia (ABS 2023), the longer-term impacts of rough sleeping on health are profound due to issues such as poor nutrition, living in harsh environments and high rates of injury (Fazel et al. 2014).

Severe overcrowding is the most common form of homelessness in Australia and is associated with different health impacts. For example, severe overcrowding places stress on the infrastructure of the dwelling, such as food preparation areas, bathrooms, laundry facilities and sewerage systems. It may lead to more rapid transmission of infectious disease (including COVID-19) and induce psychological stress (AIHW 2014; Buckle et al. 2020).

Life expectancy of people experiencing homelessness

Regardless of the form of homelessness, international research on the gap in life expectancy consistently reveals large differences among those who are experiencing homelessness compared with those who are not:

- more than 30 years in the United Kingdom and the United States (Maness and Khan 2014; Perry and Craig 2015)

- more than 10 years for people in marginal housing in Canada (Hwang et al. 2009).

Australian studies have suggested people who were homeless die an average of 22 to 33 years younger than those who are housed (Knaus 2024; Zordan et al. 2023).

Research has shown that much of the mortality gap is due to conditions which could be effectively treated with appropriate health care (Aldridge et al. 2019). A study from Scotland found that interactions with health services increased in the years prior to becoming homeless, with a peak in interactions around the time of the first assessment as homeless – particularly for services related to mental health or drug and alcohol misuse (Waugh et al. 2018). This study suggests that health services could play a role in preventing homelessness by identifying risk factors, and early intervention for specific groups.

Despite the worse health outcomes for people at risk of or experiencing homelessness, there is evidence that this effect can be reversed with appropriate housing. Internationally, some of the health benefits associated with secure housing following a period of insecure housing were:

- decreased rates of hospitalisation

- reduced transmission of infectious diseases

- improved mental health symptoms

- overall improved wellbeing (Carnemolla et al. 2020).

Self-assessed health

In 2014, around 1 in 4 (26%) people in Australia who had ever experienced homelessness assessed their health as fair or poor, compared with 14% of those who had not experienced homelessness (ABS 2015). Note that the data source is limited to people who had experienced homelessness but who were living in private dwellings at the time of the survey.

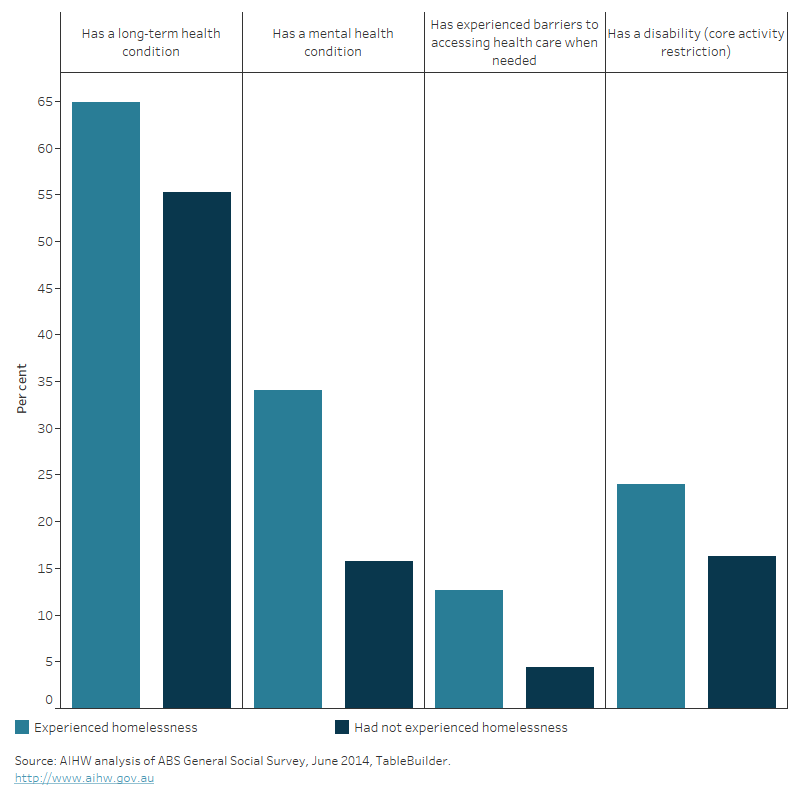

In general, a higher proportion of people who reported at least one experience of homelessness had a health condition or disability, compared with those who had never had an experience of homelessness (Figure 1). People who had experienced homelessness were more likely to report having a mental health condition or a long-term health condition, with depression, back pain or back problems, anxiety, and asthma the most commonly reported.

Figure 1: Self-assessed health status, by experience of homelessness, 2014

The bar chart shows there was a higher proportion of individuals self- reporting a long-term health condition, a mental health condition, disability or having experienced barriers when accessing health care when needed amongst those who had experienced homelessness compared with those who had not experienced homelessness.

Specialist Homelessness Services clients – health services needs

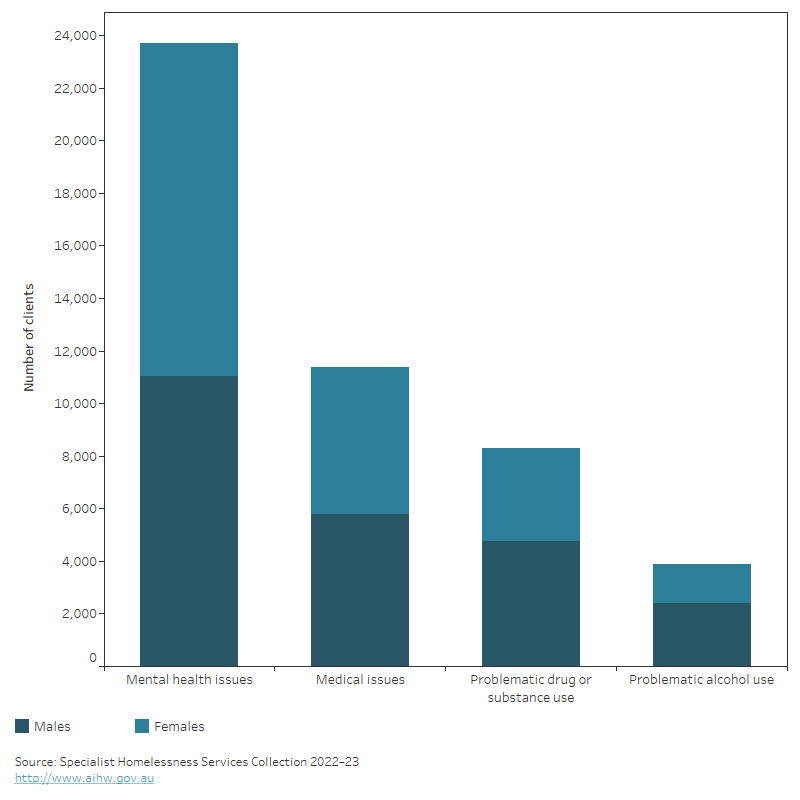

In 2022–23, around 1 in 4 (27% or 31,600) SHS clients who were homeless when they first presented to a SHS agency for assistance identified health-related reasons for seeking support (AIHW 2023). Clients may require assistance for more than one reason. Of the 31,600 people experiencing homelessness and reporting health‑related reasons (Figure 2):

- 23,700 clients identified mental health issues

- 11,400 clients identified medical issues

- 8,300 clients identified problematic drug or substance use

- 3,900 clients identified problematic alcohol use.

Figure 2: Number of SHS clients who were homeless at first presentation, by sex and health-related reasons for seeking assistance, 2022–23

The stacked vertical bar graph shows the number of male and female clients who were homeless at first presentation to a specialist homelessness service by health-related reasons for seeking assistance. For both males and females, the most common health-related reason for seeking assistance was mental health issues, followed by medical issues, problematic drug or substance use and problematic alcohol use. These reasons for seeking assistance were more commonly reported for males than females except for mental health issues.

SHS agencies provide various services to clients, from accommodation to more specialised services such as health or medical services. When a SHS agency is unable to provide specialised services, clients can be referred to another agency, with health-related services among the most commonly referred service types (AIHW 2023).

In 2022–23, SHS clients who were homeless at first presentation needed a range of health-related services:

- around 13,300 clients needed health/medical services

- over 5,000 needed drug/alcohol counselling (Table 1).

Individual clients may have more than one need and SHS data does not describe whether referred clients eventually received the health care needed.

Specialised health-related services | Number of clients | Provided as percentage of need identified | Referred only as percentage of need identified | Not provided or referred as percentage of need identified(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Health/medical services | 13,271 | 58.7 | 19.2 | 22.1 |

Mental health services | 12,074 | 46.6 | 18.7 | 34.7 |

Drug/alcohol counselling | 5,031 | 46.0 | 17.3 | 36.8 |

Specialist counselling services | 4,740 | 53.7 | 18.1 | 28.2 |

Psychological services | 4,391 | 35.4 | 23.2 | 41.4 |

Child specific counselling services | 2,995 | 54.3 | 19.1 | 26.7 |

Psychiatric services | 2,939 | 34.2 | 20.7 | 45.1 |

Family planning support | 1,456 | 57.5 | 11.3 | 31.2 |

Pregnancy assistance | 1,274 | 59.7 | 12.8 | 27.6 |

Physical disability services | 1,123 | 43.8 | 17.3 | 38.9 |

(a) Includes clients who refuse a service.

Source: Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2022–23, unpublished.

Barriers to accessing health care

Homelessness has a substantial impact on a person’s health and presents challenges for people to access appropriate and effective medical care, including ongoing care (Davies and Wood 2018).

In 2014, 13% of people who experienced homelessness at least once in the previous 10 years were more likely to report experiencing a barrier to accessing health care, compared with 4.4% who had not experienced homelessness (ABS 2015). Among people unable to obtain health care when needed, 2 in 5 (40%) identified the cost of service as the main barrier to access, followed by long waiting times or lack of appointment availability (ABS 2015).

Individual risk factors such as illness and poor health can be a barrier to receiving health care. For example, mental illness can influence both being able to attend appointments and the effectiveness of health care provided (Davies and Wood 2018). The stigma associated with receiving mental health care, feeling stereotyped or judged can also have an impact.

Physical barriers pose further challenges. For example, being able to afford public transport to attend appointments, having no mailing address or phone to receive appointment reminders, and being able to keep medications secure are difficulties faced by people in transient housing such as rough sleeping, couch surfing or short-term accommodation.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on the health of people experiencing homelessness, see:

- Specialist homelessness services annual report

- Housing data dashboard

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census of Population and Housing: estimating homelessness, 2021

- ABS Information Paper–a statistical definition of homelessness, 2012

For more information on this topic, see Homelessness services.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2015) General Social Survey: summary results, Australia, 2014. ABS website, accessed 13 October 2023.

ABS (2019) General Social Survey: summary results, Australia, 2019, ABS website, accessed 13 October 2023.

ABS (2023) Estimating Homelessness: Census, ABS website, accessed 19 January 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2014). Housing circumstances of Indigenous households: tenure and overcrowding. Cat. no. IHW 132. Canberra: AIHW.

AIHW (2023) Specialist Homelessness Services annual report. Cat. no. HOU 333. Canberra: AIHW.

Aldridge RW, Menezes D, Lewer D, Comes M, Evans H, Blackburn RM et al. (2019) ‘Causes of death among homeless people: a population-based cross-sectional study of linked hospitalisation and mortality data in England’ Wellcome Open Research 4:49, https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15151.1

Buckle C, Gurran N, Phibbs P, Harris P, Lea T and Shrivastava R (2020) Marginal housing during COVID-19, AHURI. Viewed 17 January 2024.

Carnemolla P and Skinner V (2021) ‘Outcomes Associated with Providing Secure, Stable, and Permanent Housing for People Who Have Been Homeless: An International Scoping Review’, Journal of Planning Literature, 36(4): 508-525, https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122211012911

Davies A and Wood L (2018) ‘Homeless health care: meeting the challenges of providing primary care’, The Medical Journal of Australia, 209(5):230–234, https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.01264

Fazel S, Geddes J and Kushel M (2014) ‘The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations’, The Lancet, 384 (9953):1529–1540, https://doi.org/10.1016S0140-6736(14)61132-6

Fitzpatrick S, Bramley G and Johnsen S (2013) ‘Pathways into Multiple Exclusion Homelessness in Seven UK Cities’, Urban Studies, 50(1), 148-168, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012452329

Goode J, Hoang H and Crocombe L (2018) ‘Homeless adults’ access to dental services and strategies to improve their oral health: a systematic literature review’, Australian Journal of Primary Health, 24:287-298, https://doi.org/10.1071/PY17178

Huang C, Foster H, Paudyal V, Ward M and Lowrie R (2022). ‘A systematic review of the nutritional status of adults experiencing homelessness’ Public Health, 208: 59-67, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.04.013

Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O'Campo PJ, Dunn JR (2009) ‘Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study’, BMJ, 339:b4036, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4036

Knaus C (5 Feb 2024) ‘Homeless Australians are dying at age 44 on average in hidden crisis’, The Guardian, accessed 5 February 2024.

Larney S, Conroy E, Mills KL, Burns L, Teesson M (2009) ‘Factors associated with violent victimisation among homeless adults in Sydney, Australia’, Aust N Z J Public Health, 33(4): 347-51, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00406.x

Maness DL and Khan M (2014) ‘Care of the homeless: an overview’, American Family Physician 89: 634–640.

Morrison D S (2009) ‘Homelessness as an independent risk factor for mortality: results from a retrospective cohort study’, International Journal of Epidemiology, 38(3): 877–883, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp160.

Perry J and Craig TKJ (2015) ‘Homelessness and mental health’, Trends in Urology and Men’s Health, 6(2):19–21, https://doi.org/10.1002/tre.445

Waugh A, Clarke A, Knowles J and Rowley D 2018. Health and homelessness in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

Wise C and Phillips K (2013) ‘Hearing the silent voices: narratives of health care and homelessness’, Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(5):359–67, https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.757402

Zaretzky K and Flatau P (2013) ‘The cost of homelessness and the net benefit of homeless programs: a national study’, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. Viewed January 2020.

Zordan R, Mackelprang JL, Hutton J, Moore G and Sundararajan V (2023) ‘Premature mortality 16 years after emergency department presentation among homeless and at risk of homelessness adults: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study’, International Journal of Epidemiology, 52(2): 501–511, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyad006