Adults in prison

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Adults in prison, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Adults in prison. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/adults-in-prison

MLA

Adults in prison. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 15 November 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/adults-in-prison

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Adults in prison [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/adults-in-prison

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Adults in prison, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/adults-in-prison

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

People in prison are some of the most vulnerable people in society and often come from disadvantaged backgrounds. People who spend time in prison experience higher rates of homelessness, unemployment, mental health disorders, chronic physical disease, communicable disease, tobacco smoking, high-risk alcohol consumption, and illicit use of drugs than the general population (AIHW 2019).

Adults in Australia who commit or allegedly commit crimes are managed by the criminal justice system. There are 116 custodial correctional facilities across Australia (SCGRSP, 2023). On 30 June 2022, there were around 40,600 adults in custody (ABS 2023b). Australia has 9 legal systems, 1 for each state and territory and 1 for the Commonwealth. While the criminal justice systems in each jurisdiction are similar, they remain separate. Therefore, laws, penalties and arrangements for administering justice differ across state and territory boundaries (ABS 1997).

Australia's prison population over time

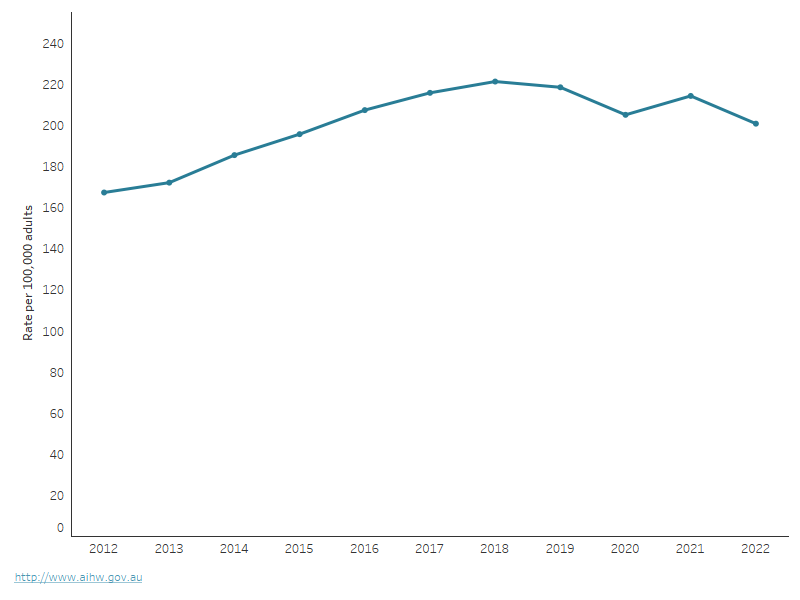

Over the decade to 2022, Australia's prison population increased in number and as a proportion of the population. Despite a slight drop recently, the average daily prison population grew from almost 29,400 at 30 June 2012 to around 40,600 at 30 June 2022. During the same period, the imprisonment rate increased from 167 to 201 per 100,000 adults (Figure 1). The most common offences for people in Australian prisons as at 30 June 2022 were acts intended to cause injury (26%), sexual assault and related offences (16%) and illicit drug offences (14%) (ABS 2023b).

Figure 1: Adult imprisonment rate, 2012 to 2022

This figure shows the adult imprisonment rate over time, from 2012 to 2022. It shows a steady rise from 167 in 2012 to 201 per 100,000 adults in 2022.

Source: ABS 2023b.

Overrepresentation of population groups in prison

When comparing the 2022 prison population to the general adult population, people in prison were:

- more likely to be male – more than 9 in 10 (93%) of the adult prison population were male, compared with 5 in 10 (50%) of the general adult population (ABS 2023a, 2023b)

- more likely to identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people – nearly 1 in 3 (32%) of the adult prison population were First Nations people, compared with 3.8% of the general adult population (ABS 2022, 2023b) (see Community safety for First Nations people)

- more likely to be younger – almost 2 in 3 (63%) of the adult prison population were aged 18–39, compared with about 1 in 3 (30%) in the general adult population (ABS 2023a, 2023b).

July 2020 saw the release of The National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Target 10 of the agreement aims to reduce the overrepresentation of First Nations adults in the criminal justice system. The target is to reduce the rate of First Nations adults in incarceration by at least 15% by 2031 (Joint Council on Closing the Gap 2020).

Health of people in prison

People in prison have higher levels of mental health problems, risky alcohol consumption, tobacco smoking, illicit drug use, chronic disease and communicable diseases than the general population (AIHW 2023). This means they have substantial and complex health and welfare needs, often long term or chronic. The health of people in prison is sufficiently poorer than that of the general community that people in prison are often considered to be 'old' at age 50–55 (Williams et al. 2014).

The National Prisoner Health Data Collection

Since 2009, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) has run the National Prisoner Health Data Collection (NPHDC), over a 2-week period, every 3 years. The 2022 NPHDC has the most recent available data, which is presented on this page.

According to the 2022 NPHDC:

- Just over half (52%) of prison entrants reported a history of one or more selected chronic conditions (asthma, arthritis, back problem/s, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, pulmonary disease and osteoporosis) (AIHW 2023).

- One in 2 (51%) prison entrants reported a previous diagnosis of a mental health disorder, including drug and alcohol abuse.

- Female prison entrants (63%) were more likely than male prison entrants (49%) to report a history of a mental health condition.

- Non-Indigenous prison entrants (60%) were more likely to report a history of a mental health condition than First Nations prison entrants (43%) (AIHW 2023).

Entering and leaving prison can be highly stressful for those in the prison system. The experience of being in prison, the prison environment, relationships with other people in prison, family, housing and employment, as well as alcohol and other drug use may all be potential causes of concern and distress for people in prison.

Around 2 in 3 (68%) prison entrants had been in prison before and 2 in 5 (41%) prison entrants had been in prison within the previous 12 months (AIHW 2023).

Prison entrants were asked about their recent psychological distress levels, and about their perceived reasons for any distress. In 2022, just over 2 in 5 (43%) prison entrants scored high or very high levels of psychological distress, with female prison entrants more likely to score high or very high levels (63%) when compared with male prison entrants (40%) (AIHW 2023).

Employment status of people in prison

The ability to gain and maintain employment is key to successful reintegration of people formerly in prison into the community, post release. Many people in prison, particularly First Nations people, have complex and sometimes traumatic histories and experiences which remain following release from prison and can make employment difficult (COAG 2016).

Less than half (46%) of prison entrants reported they were unemployed during the 30 days before prison (AIHW 2023).

People in prison come from a group who already face difficulties in gaining employment. They generally have low levels of education, low socioeconomic position, high levels of drug and alcohol misuse, high levels of mental health issues and poor work histories. Imprisonment adds to this mix, making it even more difficult for people leaving prison to find a job, particularly for those who have been in prison for longer than 6 months (Ramakers et al. 2014).

Almost 2 in 5 (38%) prison dischargees reported they had paid employment organised to start within 2 weeks of release from prison (AIHW 2023).

Education prior to entering prison

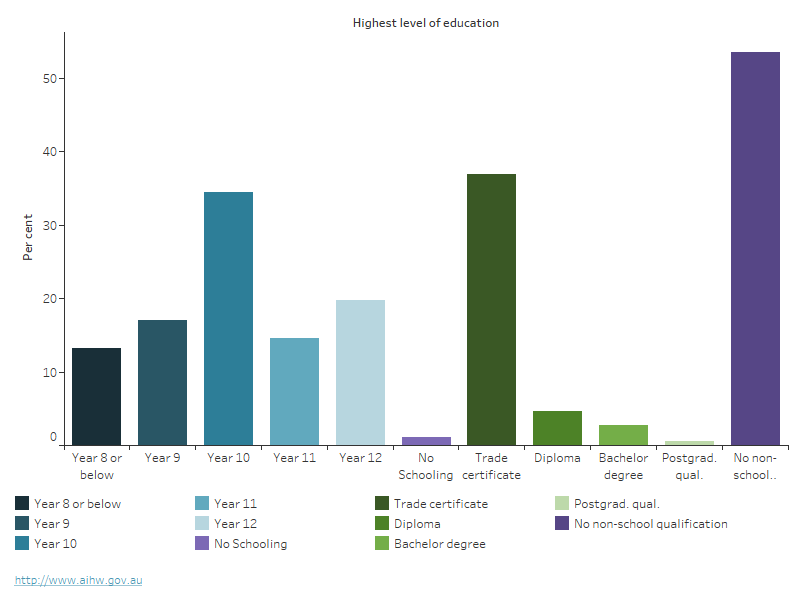

Education is a recognised social determinant of health, with lower levels of education associated with poorer health (Mitrou et al. 2014). People in prison have lower levels of educational attainment and higher levels of learning difficulties and learning disabilities than people in the general community (AIHW 2015; Kendall and Hopkins 2019). Lower levels of educational attainment are associated with poorer employment opportunities and outcomes, and unemployment is a risk factor for incarceration and for reoffending after release (Baldry et al. 2018).

In the NPHDC, prison entrants were asked about the highest level of schooling they had completed and qualifications they attained other than school.

In 2022, prison entrants were more likely than the general population (aged 15–74) to have had an education level of year 10 or below (66% compared with 16%) (ABS 2022; AIHW 2023). Of prison entrants, 13% had completed year 8 or below as their highest level of education. A total of 1.1% had no formal schooling.

Education at the tertiary level was not common – the highest level of completed education for entrants was a diploma (4.6%), followed by a bachelor degree (2.7%), and a postgraduate qualification (0.5%) (Figure 2).

Prison entrants were less likely than the general population (20% compared with 77%) to report they had completed the equivalent of year 12 (ABS 2022; AIHW 2023).

Figure 2: Highest level of education achieved by prison entrants, 2022

This figure shows the highest level of educational attainment reported by prison entrants in 2018. It shows that 15% had Year 8 or below, 17% had Year 9, 29% had Year 10, 16% had Year 11, 19% had Year 12 and 2% had either no schooling or their education level was unknown.

Source: AIHW 2023.

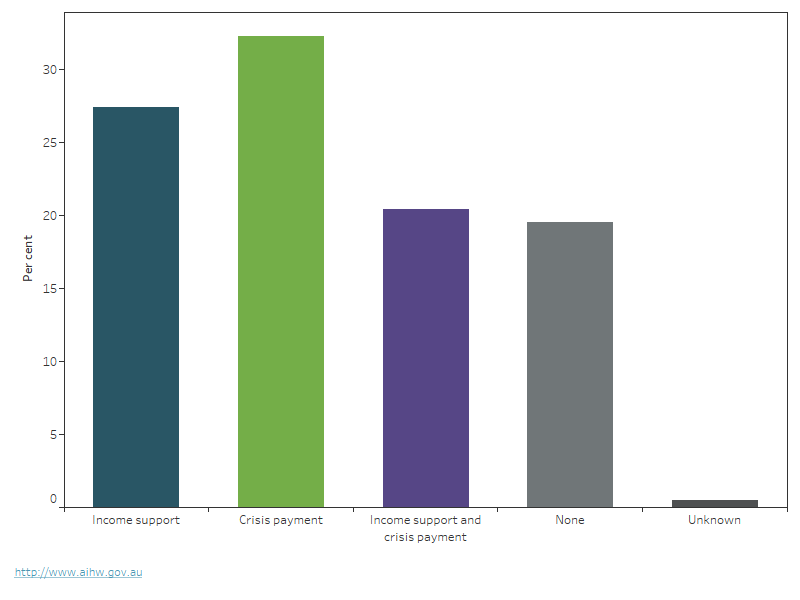

Income support following release from prison

On average people who are unemployed have poorer outcomes than people who are employed. This includes mental health issues, alcohol and other drug use disorders, and criminal offending (Fergusson et al. 2014; Winter et al. 2019).

Most (80%) prison dischargees in 2022 were expecting to receive some form of financial assistance from Centrelink after release (Figure 3). Just over 1 in 4 (27%) expected to receive income support (including Disability Support Pension) and a further 32% a crisis payment. Another 20% of prison discharges expected to receive both payments.

Figure 3: Expected income source of prison dischargees, 2022

This figure shows the source of income prison dischargees expect to receive following release from prison. It shows that 23% expected to receive an income support payment including the disability support pension, 28% expected to receive a crisis payment and 26% expected to receive both a crisis and income support payment. For 12% of discharges their income source was unknown and 10% had no source of income post release.

Note: Proportions are rounded to whole numbers, so components may not sum to total expecting to receive some form of financial assistance from Centrelink after release.

Source: AIHW 2023.

Impact of COVID-19 in the prison setting

From March 2020, a range of measures were introduced in adult prisons to reduce the impact of COVID-19, including vaccinations, social distancing, virtual visits and the use of personal protective equipment such as face masks.

People in prison are known to have a high vulnerability to infectious diseases due to the living conditions within prison (Ndeffo-Mbah et al. 2018) and as such, COVID-19 poses a serious risk to the physical health of this population. Measures introduced to reduce the spread of COVID-19 are also likely to have had an impact on the mental, emotional and social wellbeing of a person in prison (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). However, there is currently limited data available to understand the extent to which COVID-19 has impacted the health and wellbeing of people in Australia’s prisons.

In 2022, almost 4 in 5 (79%) prison entrants reported they had received a COVID-19 vaccine. Of these prison entrants:

- 6.5% had received 1 dose

- 36% had received 2 doses

- 47% had received 3 doses

- 8.8% had received 4 or more doses.

In prison, 84% of dishargees reported being quarantined or isolated due to COVID-19.

For more information on current COVID-19 measures and reported COVID-19 cases within prisons in each state and territory, see:

- New South Wales Corrective Services

- Corrections Victoria

- Queensland Corrective Services

- Western Australia Corrective Services

- South Australia Department for Correctional Services

- Tasmania Prison Service

- Australian Capital Territory Corrective Services

- Northern Territory Correctional Services.

Where do I go for more information?

For more on this topic, see People in prison.

For more information on people in Australian prisons see:

- AIHW reports:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics:

- Crime and Justice

- Prisoners in Australia – key statistics.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (1997) Australian Social Trends, 1997, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 8 May 2023.

ABS (2022) Education and Work, Australia, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 6 September 2023.

ABS (2022a) Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2021, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

ABS (2023a) National, state and territory population, June 2022, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

ABS (2023b) Prisoners in Australia, 2022, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2015) The health of Australia's prisoners 2015, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

AIHW (2019) The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

AIHW (2023) The health of people in Australia's prisons 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 15 November 2023.

Baldry E, Bright D, Cale J, Day A, Dowse L, Giles M, Hardcastle L, Graffam J, McGillivray J, Newton D, Rowe SD and Wodak J (2018) A future beyond the wall: improving post-release employment outcomes for people leaving prison: final report, UNSW Sydney, doi:10.26190/5b4fd2de5cfb4.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) (2016) Prison to work report, 2016, COAG Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2020) CDNA National Guidelines for COVID-19 Outbreaks in Correctional and Detention Facilities, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2023.

Fergusson DM, McLeod GF and Horwood LJ (2014) ‘Unemployment and psychosocial outcomes to age 30: A fixed-effects regression analysis’, Aust N Z J Psychiatry 48:735–42, doi:10.1177/0004867414525840.

Joint Council on Closing the Gap (2020) National Agreement on Closing the Gap, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government, accessed 28 February 2023.

Kendall A and Hopkins T (2019) ‘Inside out literacies: literacy learning with a peer-led prison reading scheme', International Journal of Bias, Identity and Diversities in Education, 4(1):18, doi:10.4018/IJBIDE.2019010106.

Mitrou F, Cooke M, Lawrence D, Povah D, Mobilia E, Guimond E, and Zubrick S (2014) ‘Gaps in Indigenous disadvantage not closing: a census cohort study of social determinants of health in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand from 1981–2006’, BMC Public Health 14:201, doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-201.

Ndeffo-Mbah M, Vigliotti V, Skrip L, Dolan K and Galvani A (2018) ‘Dynamic Models of Infectious Disease Transmission in Prisons and the General Population’, Epidemiologic Reviews 40: 40–57, doi:10.1093/epirev/mxx014.

Ramakers A, Apel R, Nieuwbeerta P, Dirkzwager AJE and Van Wilsem J (2014) ‘Imprisonment length and post-prison employment prospects’, Criminology 52:399–427, doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12042.

SCGRSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Services) (2023) Report on Government Services 2023, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 8 May 2023.

Williams BA, Ahalt C and Greifinger RB (2014) The older prisoner and complex chronic medical care. In: Prisons and health, World Health Organisation, 165–70.

Winter RJ, Stoové M, Agius PA, Hellard ME and Kinner SA (2019) ‘Injecting drug use is an independent risk factor for reincarceration after release from prison: a prospective cohort study’, Drug and Alcohol Review, 38(3):254-63, doi:10.1111/dar.12881.