Community safety for First Nations people

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Community safety for First Nations people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Community safety for First Nations people. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-community-safety

MLA

Community safety for First Nations people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-community-safety

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Community safety for First Nations people [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-community-safety

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Community safety for First Nations people, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-community-safety

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Safe communities, where people feel protected from harm within their home, workplace and community, are important for physical and mental wellbeing. The feeling of being safe enables a better quality of life and the capacity to be involved in the community in a positive way, both of which are protective factors for social and emotional wellbeing (AIHW and NIAA 2022a; Commonwealth of Australia 2017). While the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people feel safe in their communities and do not experience negative outcomes, they tend to experience greater rates of hospitalisation and death as a result of violence than the wider community (AIHW and NIAA 2022a).

Many factors influence community safety for First Nations people. Stronger connections to culture and Country, amongst other positive cultural determinants, improve outcomes for community safety (Commonwealth of Australia 2017). Factors that lead to unsafe situations include long-term social disadvantage and the ongoing impact of past dispossession and forced child-removal policies, which result in intergenerational trauma and breakdowns of traditional culture and kinship practices (Commonwealth of Australia 2018; Healing Foundation 2023).

This page focuses on First Nations people and their experiences of safety and violence in the community, contact with child protection services, and contact with criminal justice systems.

Closing the Gap targets

In 2020, all Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations worked in partnership to develop the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement), built around 4 Priority Reforms. The National Agreement also identifies 19 targets across 17 socioeconomic outcome areas. Four of these targets directly relate to community safety, monitored annually by the Productivity Commission and reported in their Closing the Gap Information Repository Dashboard.

National Agreement on Closing the Gap: community safety-related targets

Outcome area 10: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults are not overrepresented in the criminal justice system

- Target: By 2031, reduce the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults held in incarceration by at least 15 per cent (from an age-standardised rate of 2,142.9 per 100,000 in 2019 to 1,821.5 per 100,000 by 2031).

- Status: In 2021, the age-standardised imprisonment rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults was 2,222.7 per 100,000, which was higher than the target trajectory rate for 2021 of 2,089.3 per 100,000 population (Productivity Commission 2022a).

Outcome area 11: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are not overrepresented in the criminal justice system

- Target: By 2031, reduce the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people (10–17 years) in detention by at least 30 per cent (from 31.9 per 10,000 in 2018–19 to 22.3 per 10,000 by 2031).

- Status: In 2020–21, the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people (10–17 years) in detention was 23.2 per 10,000, which was lower than the target trajectory rate of 30.3 per 10,000 population in 2020–21 (Productivity Commission 2022b).

Outcome area 12: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are not overrepresented in the child protection system

- Target: By 2031, reduce the rate of over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care by 45 per cent (from 54.2 per 1,000 in 2019 to 29.8 per 1,000 by 2031).

- Status: In 2021, the rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home care was 57.6 per 1,000, which is higher than the target trajectory rate of 50.1 per 1,000 population (Productivity Commission 2022c).

Outcome area 13: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and households are safe

- Target: By 2031, the rate of all forms of family violence and abuse against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children is reduced by at least 50%, as progress towards zero (from 8.4% in 2018–19 to 4.2% by 2031).

- Status: The target trajectory of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females aged 15 years and older experiencing domestic physical or threatened physical harm was a reduction from 8.4% in 2018–19 to 7.4% in 2021–22. However, at the time of writing, progress towards this target could not be assessed because there were no new data on self-reported experiences of violence since the baseline year of 2018–19 (Productivity Commission 2022d).

Community experiences of safety and violence

This section covers information on feelings of safety and experiences of violence using a range of data sources, including the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15 (NATSISS), the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 (NATSIHS), the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Causes of Death Collection, the AIHW National Mortality Database (NMD) and the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) National Homicide Monitoring Program.

Feeling of safety

Feeling safe is an indicator of how an individual perceives their community; those who feel safe are able to live a better quality and healthier life and are more likely to engage in the community, and the community as a whole faces a lower incidence of, and costs from, injuries and violence (AIHW and NIAA 2022a). The most recent data on feeling of safety comes from the NATSISS.

In 2014–15, among First Nations people aged 15 and over who reported they walked alone in their local area after dark:

- 68% said they felt safe or very safe

- 12% felt neither safe nor unsafe

- 20% felt unsafe or very unsafe.

For those who spent time home alone after dark:

- 87% felt safe or very safe

- 5% felt neither safe nor unsafe

- 8% felt unsafe or very unsafe.

Experiences of physical or threatened violence

In an Indigenous community context, where family and kinship networks can be broad and complex, the term ‘family violence’ can be considered as covering relevant issues and behaviours within a broader set of relationships. Interventions to address family violence have therefore moved away from the approach of treating incidents as one-off events, and instead follow holistic, culturally appropriate approaches that are integrated into communities. For more information on these programs, see Family violence prevention programs in Indigenous communities. Also see Family, domestic and sexual violence.

Results from the latest NATSIHS indicate that in 2018–19, 16% (an estimated 76,900) of First Nations people aged 15 and over had experienced physical and/or threatened physical harm in the preceding 12 months, while 6.3% (an estimated 30,900) experienced physical harm. Of those experiencing physical harm, 74% believed that the offender was under the influence of alcohol or other substances during the most recent incident.

Assault hospitalisations

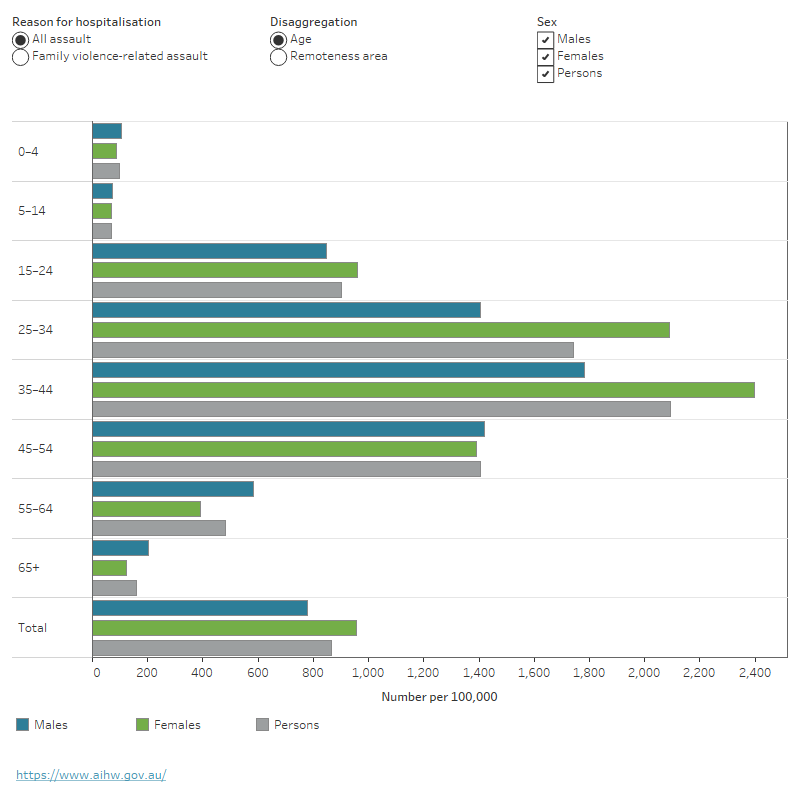

In the two-year period from 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2021, there were 14,954 assault hospitalisations for First Nations people, accounting for 32% of all assault hospitalisations (a rate of 867 per 100,000 hospitalisations). The rates were highest for First Nations females living in Remote and Very remote areas (Figure 1).

First Nations people were 15 times as likely to be hospitalised for assault as non-Indigenous Australians (age-standardised rates of 975 compared with 67 per 100,000, respectively). The ratio was higher for females, with First Nations females being 27 times as likely as non-Indigenous females to be hospitalised for assault.

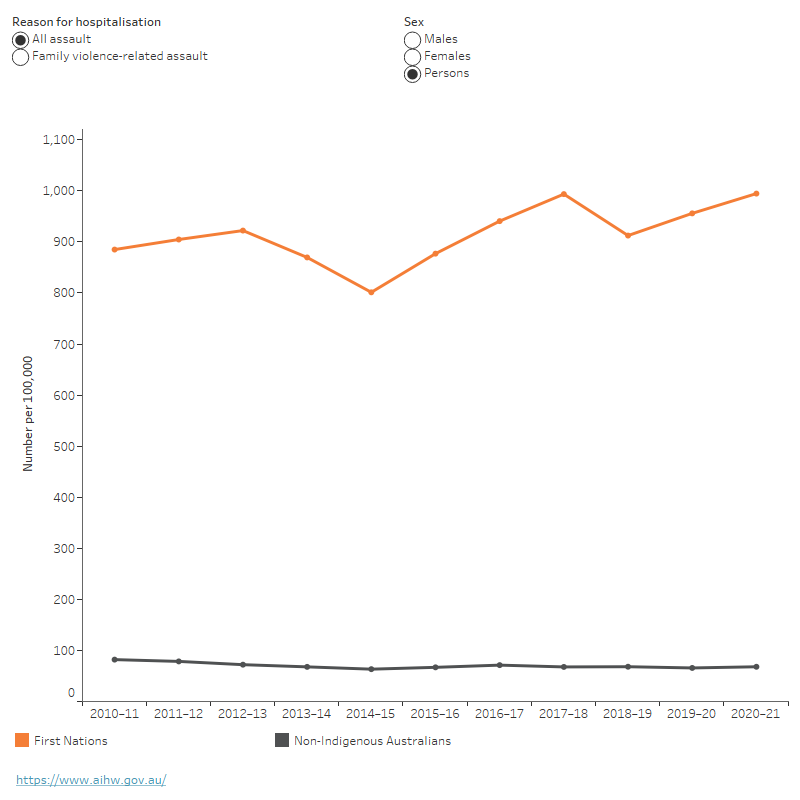

Between 2010–11 and 2020–21 there was a 12% increase in the age-standardised rate of assault hospitalisations for all First Nations people (from 885 to 995 per 100,000 population) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Hospitalisations for assault, First Nations people, by sex, age and remoteness, Australia, 2019–20 to 2020–21

This bar chart shows that by age, hospitalisation rates for assault were highest for First Nations people aged 35–44, 2,095 per 100,000. By area of remoteness, rates were highest in Very remote areas, 2,560 per 100,000. By age, hospitalisation rates for family violence-related assault were also highest for First Nations people aged 35–44, 1,093 per 100,000. By area of remoteness, rates were highest in Very remote areas, 1,512 per 100,000. Across disaggregations, rates for both assault outcomes were generally higher for First Nations females than for First Nations males.

Notes

- Categories are based on the ICD-10-AM 10th edition. Causes of injury are based on the first reported external cause as ‘Assault’ ICD-10–AM codes X85–Y09, where the principal diagnosis was ‘Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes’ (S00–T98).

- Family violence-related assault refers to non-fatal hospitalisations (mode of separation was not equal to 'died') where the perpetrator of assault was coded as 'spouse/domestic partner', 'parent' or 'other family member'.

- Remoteness area is determined by usual residence of the patient hospitalised, based on the ABS Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) 2016. Remote Victoria has been included in Outer regional.

- The rates presented for hospitalisation are crude rates.

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

In the 2-year period 2019–20 to 2020–21, of the total assault hospitalisations for First Nations people, half (7,527 assaults) were family violence-related. However, the AIHW has previously found that the number of hospitalisations due to family violence is likely to be an undercount because the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator may be unknown or unreported (AIHW 2021c).

The remaining 7,419 assault hospitalisations were due to assault perpetrated by a carer, acquaintance or friend; official authorities; person unknown to the victim; multiple people unknown to the victim; other specified person or an unspecified person.

Among First Nations people, the rate of family violence-related assault was:

- higher for females compared with males

- highest for those aged 35–44 compared with other age groups

- highest in Remote and Very remote areas of Australia compared with non-remote areas (Figure 1).

Based on age-standardised rates, the rate of family-violence related assault hospitalisations for First Nations people was 29 times the non-Indigenous rate. Over the period 2010–11 to 2020–21, there was a 37% increase in the rate of family violence-related assaults for First Nations people (based on age-standardised rates), or an increase from 364 to 503 hospitalisations per 100,000 population (Figure 2). Note: data presented on this page may differ from that in the Injury in Australia and Family, domestic and sexual violence data in Australia reports due to differences in methodology. For more information, see Family, domestic and sexual violence.

Figure 2: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for assault, by Indigenous status and sex, Australia, 2010–11 to 2020–21

This time trend chart shows that the rate of family violence-related assault hospitalisations for First Nations people has increased slightly over the period, from 364 to 503 per 100,000, and was higher than non-Indigenous Australians in all years. The rate for First Nations females was higher than for males for the entire period, peaking at 496 per 100,000 in 2017–18. For all assault, the First Nations rate has increased slightly over the same period, from 885 to 995 per 100,000.

Notes

- Categories are based on the ICD-10-AM 11th edition (Australian Consortium for Classification Development 2019): Causes of injury are based on the first reported external cause as ‘Assault’ ICD-10–AM codes X85–Y09, where the principal diagnosis was ‘Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes’ (S00–T98). Codes from previous editions (7th to 10th) of ICD-10-AM have been mapped to 11th edition.

- Family violence-related assault refers to non-fatal hospitalisations (mode of separation was not equal to 'died') where the perpetrator of assault was coded as 'spouse/domestic partner', 'parent' or 'other family member'.

- Hospitalisation rates directly age-standardised using the Australian 2001 standard population.

- Time series analyses may be affected by changes in the quality of First Nations identification over time. Time series presentations in this report include data from both public and private hospitals across several jurisdictions, so the overall effect of changes in Indigenous identification over time is unclear. This should be taken into account when interpreting time series data.

Source: AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

COVID-19 and intimate partner violence

In response to outbreaks occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic, several states and territories imposed lockdowns to prevent the disease from spreading. As a result, women who were vulnerable to domestic violence may have been required to socially isolate with their offending partners. For some people, the pandemic also increased other stressors, such as financial hardship and social isolation, which are risk factors for domestic violence (Morgan and Boxall 2020).

Boxall and Morgan (2021) surveyed women about their experiences of intimate partner violence since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that of the women who were experiencing physical violence from their partners for the first time during the pandemic, almost 1 in 3 (29%) had been in the relationship for 11 or more years. Among women experiencing first-time violence or an escalation of violence, pandemic-related factors were the most commonly reported relationship-level factors contributing to a change in violence (Boxall and Morgan 2021). The authors noted that First Nations women were more likely to experience both physical and non-physical abuse, but the effect of the pandemic on this was unclear.

The ABS also reported on co-habiting partner violence in 2021–22 in the Personal Safety Survey. The ABS found a decrease in the prevalence of women experiencing partner violence compared to previous collection years (ABS 2023a). However, this survey did not examine factors contributing to violence and did not specifically collect data on the effect of the pandemic. No data about First Nations people has been published from this survey.

Deaths due to homicide

Information on deaths due to homicide is available from death registrations data. The AIHW reports deaths data about First Nations people for the 5 jurisdictions in which the AIHW considers the quality of First Nations identification to be adequate – New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

In these 5 jurisdictions combined, over the period 2006 to 2019, the rate of deaths due to homicide for First Nations people trended downwards, decreasing by 37% overall, from 6.9 per 100,000 to 3.8 per 100,000 (from 39 deaths in 2006 to 28 deaths in 2019).

Over the five-year period 2015 to 2019, among First Nations people:

- There were 174 deaths due to homicide.

- The rate of deaths due to homicide was 1.7 times higher for males compared with females (6.1 and 3.6 per 100,000, respectively).

- Rates were highest for those aged 35–44, at 14 per 100,000 (AIHW and NIAA 2022a).

The AIC also reports on homicides in Australia. According to AIC data, between July 2020 and June 2021, there were 22 homicide victims who were First Nations people. The offender was an intimate partner, child, parent, sibling or other relative for half (11) of these victims, including all 5 female victims. The remaining victims of homicide were male, and the offender was an acquaintance (5), a stranger (2), relationship not stated/unknown (2) or offender not identified (2) (AIC 2023).

Statistics about homicide presented on this page come from different sources and may differ due to differences in reporting periods and methodology.

Contact with child protection services

The safety of children in their homes and communities is a key part of community safety. Police, teachers, doctors, and others notify child protection services when there is a risk or perceived risk of harm to a child. Historical child welfare policies targeting First Nations people led to the Stolen Generations, and the trauma experienced by survivors and their descendants is ongoing (AIHW 2018, 2021a). The consequences of these removal policies have long-term effects, including social, physical and psychological impacts for those directly involved, as well as for their families and communities (Atkinson 2013). Child protection issues continue to be very significant for the First Nations population, reflecting this history of trauma and stressors that have impacted on parents and communities. In addition, children who are abused or neglected are at greater risk of future contact with the criminal justice system (AIHW 2022d).

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle (ATSICPP) sets out a placement hierarchy for First Nations children being placed in out-of-home care. The intention of the ATSICPP is to ensure culture, human rights and self-determination are embedded in child welfare decisions (SNAICC 2017). Placements must be made in consultation with the child’s family and community representatives, and must be geographically close to the child’s family, unless the child is placed with extended First Nations family (SNAICC 2017).

In order, priority is given to placement with:

- First Nations or non-Indigenous kin

- other First Nations members of the community

- First Nations family-based carers

- a non-Indigenous carer or in a residential setting.

As at 30 June 2021, 63% of First Nations children in out-of-home care were placed with Indigenous or non-Indigenous kin or with another First Nations carer, in accordance with the ATSICPP. This proportion has been relatively stable since 30 June 2017 (AIHW 2022a). For more information about the ATSICPP, including indicator development, see The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle indicators report.

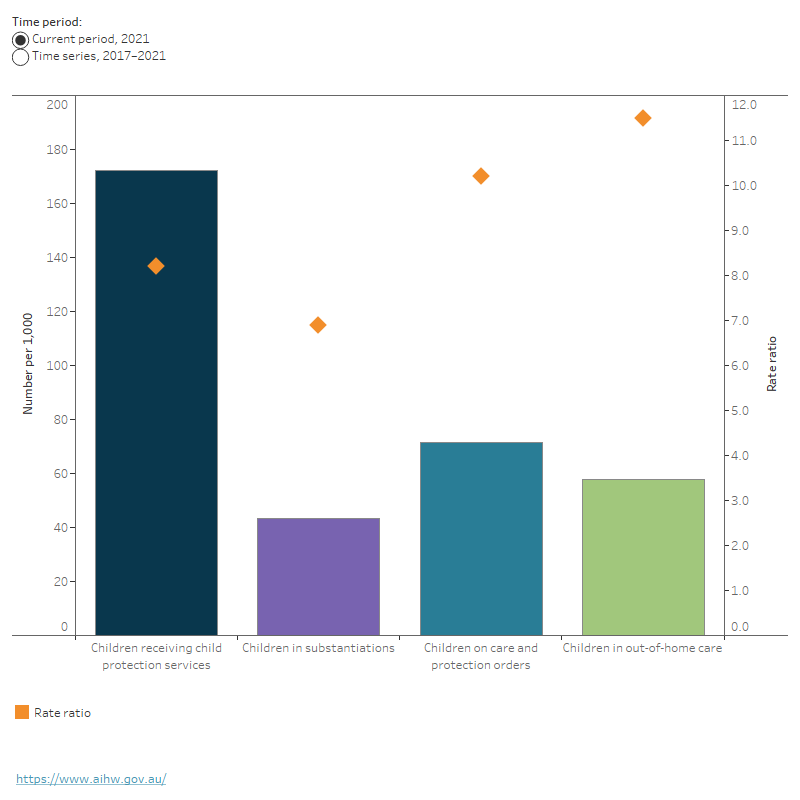

From July 2020 to June 2021:

- 14,596 First Nations children were the subject of substantiated notifications, a rate of 43 per 1,000 First Nations children (Figure 3).

- 58,034 First Nations children were receiving services, accounting for 32% of all children in Australia receiving services. This was a rate of 172 per 1,000 (AIHW 2022b).

As of 30 June 2021:

- 24,174 (71 per 1,000) First Nations children were on care and protection orders.

- Between 30 June 2017 and 30 June 2021, there was a 19% increase, from 60 per 1,000 to 71 per 1,000 (Figure 3).

- 19,480 (58 per 1,000) First Nations children were in out-of-home care.

- Between 30 June 2017 and 30 June 2021 there was a 13% increase, from 51 per 1,000 to 58 per 1,000 (AIHW 2022b) (Figure 3).

When interpreting the time series data presented in Figure 3, please note, there was a break in the time trend for substantiation data, due to a change in processes in New South Wales in 2017–2018.

Figure 3: First Nations children in the child protection system, 2017 to 2021

This bar chart shows that in 2021, there were 43 per 1,000 Indigenous children in substantiations, 72 per 1,000 First Nations children on care and protection orders, 58 per 1,000 First Nations children in out-of-home care and 172 per 1,000 First Nations children receiving child and protection services. The rate ratio with non-Indigenous children was highest for children in out-of-home care (11.5) and lowest for children in substantiations (6.9).

Notes

- Children on care and protection orders and in out-of-home care were measured as at 30 June each year. Children in substantiations are measured in financial years (in other words, 2021 indicates substantiations from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021).

- In 2017–18, New South Wales was unable to provide data on substantiations due to the implementation of a new client management system. Therefore, time trend substantiation data is not published.

- In 2018–19, all states and territories adopted a national definition of out-of-home care. The out-of-home care data have been back cast to 30 June 2017 with the national definition and may differ from those published elsewhere.

- Rate ratio is the rate for First Nations people divided by the rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: AIHW Child protection Australia 2020–21.

Impact of COVID-19 on child protection notifications

Suspicions about child abuse or neglect are often reported by schools, child care centres, and other people or services children regularly come into contact with. The COVID-19 pandemic affected daily life through restrictions on people’s movements and interactions – potentially limiting opportunities for child abuse and neglect to be detected and reported. In April 2020, the number of school notifications decreased normally as school holidays started, but upon returning to school the increase was larger than was seen in 2019. However, numbers for substantiations and out-of-home care orders remained relatively stable across the period (AIHW 2021b). The long-term impact of COVID-19 on child protection processes is still unknown; however, there have been no specific impacts on the annual data. For a more information, please see Child protection system in Australia.

Contact with criminal justice systems

Criminal justice systems are used to protect individuals and communities. This includes incarcerating people who commit serious crimes. However, imprisonment can compound existing social and economic disadvantage and affects family, children, and the broader community with intergenerational effects (AIHW and NIAA 2022b).

People in contact with the criminal justice system are at risk of poorer health and wellbeing outcomes for themselves, their family and their broader community. First Nations people experience contact with criminal justice systems, as both offenders and victims, at much higher rates than non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW and NIAA 2022b).

Youth justice

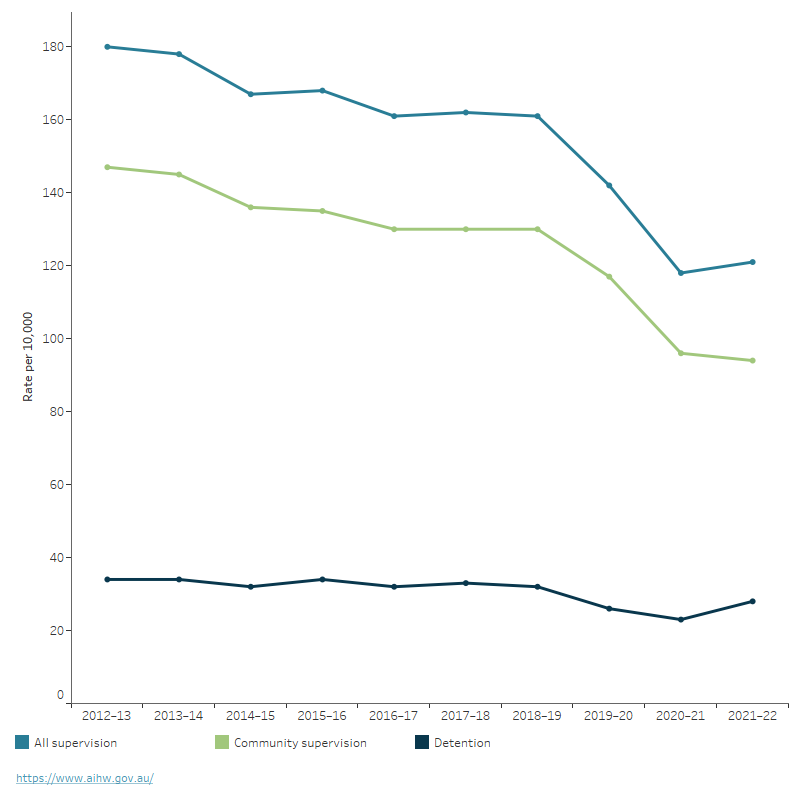

Australians under the age of 18 who have been sentenced, or are awaiting sentencing, may be placed under supervision within the community or detention facilities. Rates of supervision for First Nations people aged 10–17 have trended downwards for both community supervision and detention since 2011–12 (AIHW 2022c). Rates of community supervision have always been higher than rates of detention (Figure 4).

The rate of First Nations people aged 10–17 under supervision on an average day declined from 180 per 10,000 in 2012–13 to 121 per 10,000 in 2021–22 (Figure 4). The largest declines occurred in 2019–20 and 2020–21 (AIHW 2022c). This may be partly related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a substantial impact on the operation of courts. However, more data is required to determine the impact of the pandemic on youth justice data.

Though the rate of First Nations people aged 10–17 in supervision has decreased, in 2021–22 First Nations people were 19 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians aged 10–17 to be under supervision on an average day (121 per 10,000, compared with 6.5 per 10,000, respectively) (AIHW 2022c). (See Youth justice).

There are no national data available on the principal (most serious) offences among First Nations people under supervision.

Figure 4: Youth justice rates, First Nations people aged 10–17 under sentenced supervision on an average day, by supervision type, 2012–13 to 2021–22

This time trend chart shows that the rates of First Nations people aged 10–17 under youth justice supervision on an average day has decreased over the period, 2012–13 to 2021–22, from 180 to 121 per 10,000. The rate of First Nations people aged 10–17 on community-based supervision has also declined, from 147 to 94 per 10,000. The rate of those under detention remained relatively stable during the same period but did show a decline in 2019–20 and 2020–21.

Notes

- Trend data may differ from those previously published due to data revisions.

- Rates are number of people (aged 10–17) per 10,000 relevant population.

- Rates are not published where there were fewer than five people aged 10–17.

- Age on an average day is calculated based on the age a person is each day that they are under supervision. If a person changes age during a period of supervision, then the average daily number under supervision will reflect this. Average daily data broken down by age will not be comparable to Youth justice in Australia releases prior to 2019–20.

- Closing the Gap Target 11 focusses on rates of youth in detention only.

Source: AIHW Youth justice in Australia 2021–22.

Impact of COVID-19 on youth justice

While youth justice centres and other places of custody, courts or tribunals were considered essential services (Prime Minister of Australia 2020), COVID-19 still has had a substantial impact on the operations of these services and restrictions may have continued beyond the easing of restrictions in the general community. The impact may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In New South Wales, for example, Children’s Court hearings were vacated from 24 March to 1 May 2020 with few exceptions. This led to a decrease in the number of court finalisations between March and June 2020, which resulted in a reduction of young people in sentenced detention.

During this period, there was also a decline in unsentenced detention as more young people were discharged to bail and fewer young people had their bail revoked when breaching bail conditions (Chan 2021). More research is required to better understand the impact of COVID-19 and related social restrictions on youth justice supervision across Australia. For more information, see Youth justice.

Adult prisoners

As at 30 June 2022:

- there were 12,902 First Nations prisoners in custody, representing 32% of the prison population, up from 24% in 2006

- the majority (91% or 11,744 people) of First Nations prisoners were male

- almost 4 in 5 (78% or 10,025 people) First Nations prisoners had previously experienced adult imprisonment (ABS 2023b).

Between 30 June 2006 and 30 June 2022, the age-standardised rate of adult First Nations imprisonment increased by 61%, from 1,333 to 2,151 per 100,000 (Figure 5) (ABS 2021, 2023b).

In 2022, the age-standardised rate of imprisonment for First Nations adults was 14 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (2,151 compared with 151 per 100,000 population) (Figure 5). Among adult First Nations prisoners, the most commonly recorded most serious offences/charges were acts to cause injury (38% of prisoners), unlawful entry with intent (11%), sexual assault (10%), robbery/extortion (9%) and offences against justice (9%) (ABS 2023b).

Figure 5: Age-standardised adult imprisonment rates, by Indigenous status and sex, 2006 to 2022

This time trend chart shows that the rate of First Nations adults under imprisonment has increased over the period, from 1,333 to 2,151 per 100,000, and was higher than the rate for non-Indigenous adults. The rate for First Nations men has been higher than that for First Nations women over the period, the male rate was highest at 4,042 per 100,000 at 30 June 2021, while the female rate peaked at 30 June 2018, at 437 per 100,000.

Notes

- Data includes all persons in the legal custody of adult corrective services in all states and territories as at midnight 30 June of the reference year.

- From 2019, in all states and territories persons remanded or sentenced to adult custody are aged 18 years and over.

- In Queensland, prior to 2018, 'adult' referred to persons aged 17 years and over.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rates were revised using updated numbers based on the 2016 Census.

Source: ABS Prisoners in Australia.

Impact of COVID-19 on adult prisons

From March 2020, a range of measures were introduced in adult prisons to reduce the impact of COVID-19, including vaccinations, social distancing, virtual visits and the use of personal protective equipment such as face masks.

Due to the living conditions within prison, prisoners are vulnerable to infectious diseases (Ndeffo-Mbah et al. 2018) and as such, COVID-19 poses a serious risk to the physical health of this population. Measures introduced to reduce the spread of COVID-19 are also likely to have had an impact on the mental, emotional and social wellbeing of a person in prison (Department of Health 2020). However, there is currently limited data available to understand the extent to which COVID-19 has impacted the health and wellbeing of people in Australia’s prisons. The 2022 National Prisoner Health Data Collection included items on COVID-19. Data are scheduled for release by the AIHW in late 2023. For more information, see Adult prisoners.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on First Nations community safety, see: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework – Measure 2.10: Community safety.

For more information on contact with the justice system, see: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework – Measure 2.11: Contact with the criminal justice system.

For more information on child protection, see: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework – Measure 2.12: Child protection and Safe and Supported: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Action Plan 2023-2026.

For more information on the health impacts of family, domestic and sexual violence, see: The National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2021) Prisoners in Australia, ABS website, accessed 1 June 2023.

–– (2023a) Personal safety, Australia, ABS website, accessed 5 June 2023.

–– (2023b) Prisoners in Australia, ABS website, accessed 17 March 2023.

AIC (Australian Institute of Criminology) (2022) National Homicide Monitoring Program 2019–20, AIC website, accessed 14 December 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2018) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations and descendants: numbers, demographic characteristics and selected outcomes, AIHW website, accessed 1 June 2023.

–– (2021a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations aged 50 and over: updated analyses for 2018–19, AIHW website, accessed 1 June 2023.

–– (2021b) Child protection in the time of COVID-19, AIHW website, accessed 16 January 2023.

–– (2021c) Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence, AIHW website, accessed 1 June 2023.

–– (2022a) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle indicators [data set], AIHW website, accessed 15 December 2022.

–– (2022b) Child protection Australia 2020–21, AIHW website, accessed 5 June 2023.

–– (2022c) Data tables: Youth justice in Australia 2020–21 supplementary tables - Characteristics of young people under supervision: S1 to S33 [Data set], AIHW website, accessed 21 December 2022.

–– (2022d) Young people under youth justice supervision and their interaction with the child protection system 2020–21, AIHW website, accessed 25 January 2023.

AIHW and NIAA (2022a) 2.10 Community safety, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework website, accessed 16 January 2023.

AIHW and NIAA (2022b) 2.11 Contact with the criminal justice system, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework website, accessed 16 January 2023.

Atkinson J (2013) Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children, Resource sheet no. 21, produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse, AIHW and AIFS, accessed 25 January 2023.

Boxall H and Morgan A (2021) Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of women in Australia, AIC, accessed 25 January 2023.

Chan N (2021) ‘The impact of COVID-19 on young people in the criminal justice system’, Bureau brief number BB151, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, accessed 2 March 2022.

Commonwealth of Australia (2017) National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government, accessed 16 January 2023.

Commonwealth of Australia (2018) ‘Chapter 7: Safe and strong communities’, Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2018, PM&C, accessed 16 January 2023.

Healing Foundation (2023) Intergenerational trauma, Healing Foundation website, accessed 16 January 2023.

Morgan A and Boxall H (2020) ‘Social isolation, time spent at home, financial stress and domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic’, Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice, 609, AIC, doi:10.52922/ti04855.

Ndeffo-Mbah M, Vigliotti V, Skrip L, Dolan K and Galvani A (2018) ‘Dynamic Models of Infectious Disease Transmission in Prisons and the General Population’, Epidemiologic Reviews, 40:40–57, doi:10.1093/epirev/mxx014.

Prime Minister of Australia (2020) Update on coronavirus measures on 18 March 2020, Australian Government Department of Health, accessed 9 May 2023.

Productivity Commission (2022a) Socioeconomic outcome area 10: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults are not overrepresented in the criminal justice system, Closing the Gap Information Repository website, accessed 2 February 2023.

Productivity Commission (2022b) Socioeconomic outcome area 11: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are not overrepresented in the criminal justice system, Closing the Gap Information Repository website, accessed 2 February 2023.

Productivity Commission (2022c) Socioeconomic outcome area 12: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are not overrepresented in the child protection system, Closing the Gap Information Repository website, accessed 2 February 2023.

Productivity Commission (2022d) Socioeconomic outcome area 13: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and households are safe, Closing the Gap Information Repository website, accessed 2 February 2023.

SNAICC (Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care) (2017) Understanding and applying the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle, SNAICC website, accessed 16 January 2023.