Gambling in Australia

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Gambling in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 20 September 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Gambling in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/gambling

MLA

Gambling in Australia. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/gambling

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Gambling in Australia [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Sep. 20]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/gambling

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Gambling in Australia, viewed 20 September 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/gambling

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

This page was written by the Australian Gambling Research Centre (AGRC) at the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) for the AIHW.

Gambling is a major public policy issue in Australia, affecting the health and wellbeing of individuals and families in a range of ways. Estimates suggest that Australians lose approximately $25 billion on legal forms of gambling each year, representing the largest per capita losses in the world (Letts 2018; QGSO 2022).

The social costs of gambling – including adverse financial impacts, emotional and psychological costs, relationship and family impacts, and productivity loss and work impacts – have been estimated at around $7 billion in Victoria alone (Browne et al. 2017). Gambling-related harms affect not only the people directly involved, but also their families, peers and the wider community (Goodwin et al. 2017).

This page aims to:

- improve understanding of gambling participation and expenditure in Australia

- describe gambling-related impacts on health and wellbeing

- highlight emerging gambling trends and opportunities for improved monitoring.

Data on gambling trends should be interpreted in the context of recent global events and changes to some state and territory data collections. This includes:

- changes in the availability of gambling in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic and related government restrictions, with land-based gambling venues temporarily closed and major national and international sporting codes suspended. Individual state and territory governments implemented and eased restrictions at different times during 2020 and 2021 (for more detail see ACMA 2022, Biddle 2020, Jenkinson et al. 2020).

- changes to gambling policy and legislation in Australia by state and territories (see Section 3 of latest Australian Gambling Statistics report by the Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (QGSO))

- changes to the way wagering (see glossary) is taxed by Australian state and territories (see Table 1 of the latest Australian Gambling Statistics report by the QGSO).

Support services are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week:

Gambling participation

Gambling in the Australian adult population

In 2022 the Australian Gambling Research Centre conducted an online general community panel survey to explore gambling participation and related harm among Australian adults (AGRC 2023).

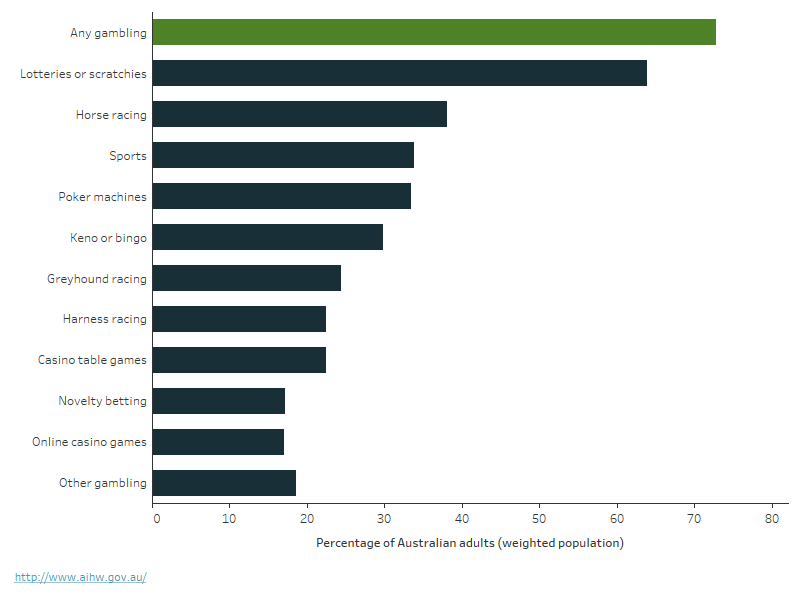

Three in 4 (73%) Australians aged 18 and over reported spending money on one or more gambling products in the past 12 months (Figure 1). Lotteries/scratchies were the product with the highest participation (64%), followed by race betting (horse, greyhound and/or harness racing, 39%), sports betting (34%) and poker machines/‘pokies’ (33%) (see glossary).

Among those who reported gambling in the past 12 months, the average number of products gambled on was 2, but around one-quarter (23%) of respondents reported gambling on 6 or more different products.

Figure 1: Gambling among Australian adults in the past 12 months, 2022

This interactive data visualisation shows the proportion of Australian adults who spent money gambling in the past 12 months (72.8%). Lotteries/scratchies were the product with the highest participation (63.8%), followed by horse racing (38.1%), sports (33.8%), poker machines (33.4%), keno/bingo (29.4%), greyhound racing (24.4%), harness racing (22.5%), casino table games (22.4%), novelty betting (17.2%) and online casino games (17.2%). Around 1 in 5 (18.5%) spent money gambling on other activities.

Notes

- Data was collected as part of an online general community panel survey conducted in July 2022. Sample consisted of 1,765 Australian residents aged 18 years and over, aligned with ABS population parameters of age, gender and location of residence (metro and non-metro).

- Recent (past 12 months) gambling participation was derived from responses regarding frequency of involvement in 13 types of gambling activities, including: Sports betting; Horse race betting; Greyhound race betting; Harness race/trots betting; Lotteries or scratchies; Keno or bingo; Poker machines (pokies); Casino table games (e.g. blackjack, poker); Online casino games; eSports; Fantasy sports; Novelty betting; and Virtual sports (see definitions of gambling activities in the glossary).

- The research was conducted by the Australian Gambling Research Centre in partnership with ORIMA Research and the Online Research Unit (ORU).

Source: Community Attitudes Survey (Australian Gambling Research Centre 2023).

Around 2 in 5 (38%) adult Australians gambled at least weekly, though this differed by gender (48% for men and 28% for women). Regular gambling was higher in adults aged 18–54 than adults aged 55 and over for all gambling activities, apart from lotteries/scratchies which was highest among those aged 55 years and over.

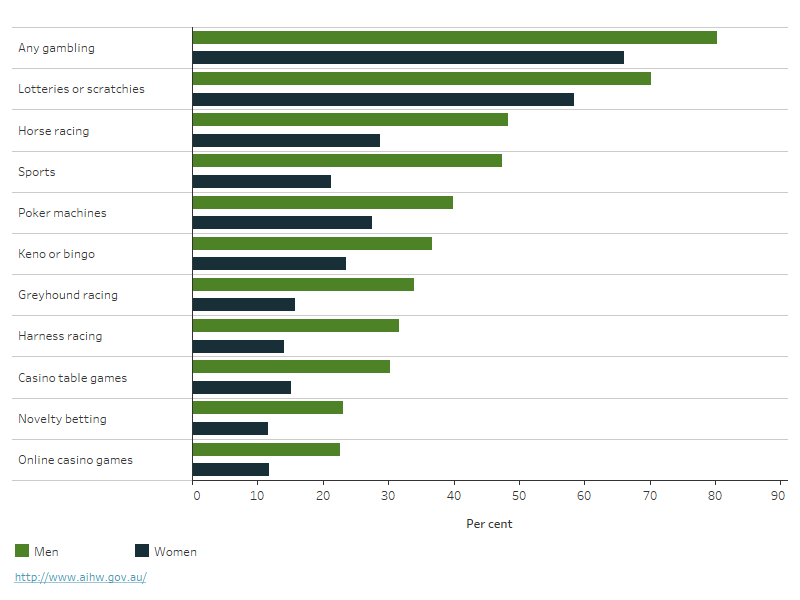

More men than women gambled on every product included in the survey (for example, sports, racing, pokies; Figure 2). Men also gambled more frequently, spent more money and were more likely to be at risk of harm during the past 12 months.

Figure 2: Gambling among Australian adults in the past 12 months, by gender, 2022

This interactive data visualisation shows males were more likely than females to spend any money gambling in the past 12 months (male 80.3% and female: 66.2%), and to gamble on each product included in the survey. For example, 47.5% of men reported spending money on sports betting, compared to 21.3 % of women.

Notes

- Data was collected as part of an online general community panel survey conducted in July 2022. Sample consisted of Australian residents aged 18 years and over, aligned with ABS population parameters of age, gender and location of residence (metro and non-metro). Male n=865; Female n=887 (total N = 1,752, excluding other genders due to small sample size).

- The research was conducted by the Australian Gambling Research Centre in partnership with ORIMA Research and the Online Research Unit (ORU).

Source: Community Attitudes Survey (Australian Gambling Research Centre 2023).

Gambling among Australian men

In 2020–21 the Ten to Men: The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health examined the prevalence, frequency and characteristics of gambling participation among Australian men (aged 18–63), and the prevalence and predictors of ‘at-risk or problem gambling’. The survey asked about gambling on 8 different products: poker machines (pokies); horse racing; sports events; greyhound racing; casino table games (for example, blackjack, roulette, but not poker); poker; esports (for money); and fantasy sports (for money).

More than 2 in 5 men (44% or an estimated 2.8 million Australian men aged 18 and over) reported having gambled in the past 12 months. Most men who gambled spent money on multiple activities, including:

- horse racing (56%)

- poker machines (54%)

- sports betting (46%) (Tajin et al. 2022).

Men who gambled on esports and fantasy sports tended to be younger (average age 32 and 33 years, respectively) than men who spent money gambling on horse racing (average age 41 years), sports betting and poker machines (average age 39 years, each) (Tajin et al. 2022).

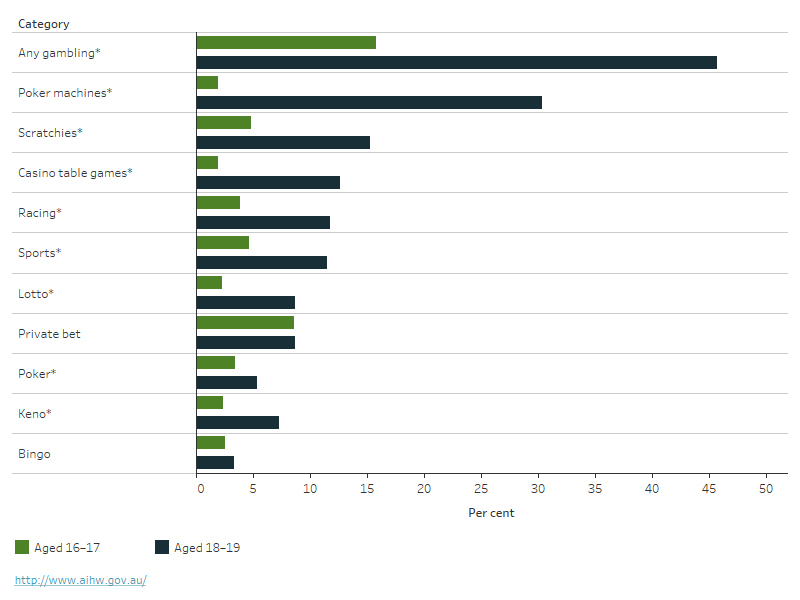

Gambling among young people in Australia

Growing Up in Australia: The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) follows the development of 10,000 children and families from across Australia. Analysis from Wave 7 (in 2016; K cohort) revealed that approximately 1 in 6 (16%) Australians aged 16–17 participated in underage gambling in the 12 months prior to survey (most commonly private betting; Figure 3). Two years later (when aged 18–19), almost half (46%) of the same cohort reported having spent money gambling. The most common activities were:

- poker machines (30%)

- instant scratch tickets (‘scratchies’ 15%)

- casino table games (13%)

- betting on horse or dog races (12%)

- betting on sports (12%) (Sakata and Jenkinson 2022).

Figure 3: Changes in gambling participation from age 16–17 years (2016) to age 18–19 years (2018) in Australia

This interactive data visualisation shows changes in gambling participation among young people aged 16-17 years and then two years later at 18-19 years (for the same sample). Any gambling in the past 12 months increased significantly from age 16-17 (15.8%) to age 18-19 (45.7%). At age 18-19 (18 is the legal age to gamble in Australia), 30.4% spent money gambling on poker machines, 15.3% scratchies, 12.7% casino table games, 11.8% racing, and 11.5% sports.

Note: LSAC K cohort, Waves 7 and 8, weighted. The asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference in results between the ages 16–17 and 18–19 (p < 0.05). The sample size varied from n = 2,937 to n = 2,466.

Source: LSAC Wave 7 (2016) and Wave 8 (2018).

Different modes of gambling

In 2011 and 2019, national telephone surveys were conducted to estimate the prevalence of online and land-based modes of gambling in Australia (Hing et al. 2014, 2021). The research found overall gambling participation (online and land-based modes combined) decreased from 64.3% in 2010–11 to 56.9% in 2019; this was mostly attributable to a decline in land-based gambling during that time, while online gambling increased by 9.4%. In 2019 the most common online products that money was spent on were lotteries, race betting and sports betting.

More recent research has examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions on gambling participation in Australia. A 2020 survey of more than 2,000 adults who gamble found that almost 1 in 3 participants signed-up for a new online betting account during COVID-19, and 1 in 20 started gambling online (Jenkinson et al. 2020). The survey also examined roughly what proportion of participants’ gambling was conducted via different modes (for example online, at land-based venues). On average, before COVID-19, around 62% of participants' gambling was conducted online; during COVID-19, this increased to 78%. Consumer surveys, key expert reports and industry data suggest that the increased spending on online gambling during the pandemic has been sustained (see Gambling Trends Study).

Gambling expenditure

Gambling expenditure data

Gambling expenditure data are compiled annually for the Australian Gambling Statistics report (QGSO 2022). This report defines expenditure as net amount lost (amount wagered minus amount won) by people who gambled in Australia up to 2019–20 (the most recent data available).

See Australian gambling statistics, 37th edition for background information and more detail on the definition of gambling products, sources of gambling data, relevant legislation and notes attached to specific tables and data items.

This page presents a summary of expenditure/losses data on legal, regulated forms of gambling in Australia, including:

- electronic gaming/poker machines operating in clubs, pubs, and hotels

- wagering on races, sports, and other approved events (for example, elections)

- gambling at casinos, including on table games, gaming machines and keno systems

- lotteries, including lotteries, lotto, pools and instant scratchies

- Keno, excluding at casinos

- other gaming, including minor gaming.

All expenditure/losses data reported on this page represents ‘real expenditure’, that is, adjusted for inflation to 2019–20 dollars to enable comparisons to previous years.

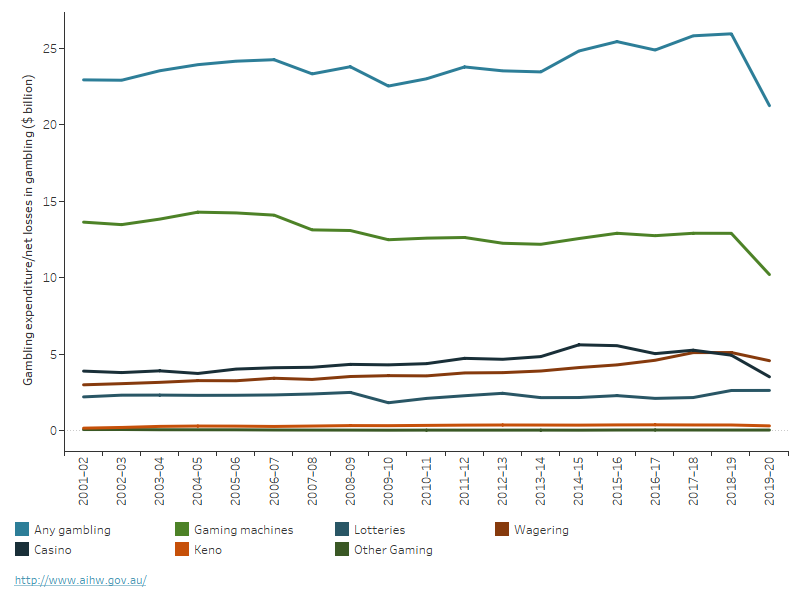

Total gambling expenditure (net losses) in Australia was $21.2 billion in 2019–20, a decrease from $25.9 billion in 2018–19 and $22.9 billion in 2001–02 (Figure 4). It is important to note that the decline in total gambling expenditure in 2019–20 mostly reflects decreases in land-based gambling expenditure such as casino gambling (down 29%) and poker machines in pubs/clubs (down 21%), which were directly impacted by temporary venue closures during the COVID-19 restrictions (see Notes in Figure 4).

During the 2001–02 to 2019–20 reporting period, poker machines in pubs/clubs accounted for 48–60% of the total gambling expenditure in Australia, followed by casino gambling (15–23%), wagering (13–22%), lotteries (8–12%), Keno (<2%) and other gaming (<1%).

Figure 4: Total real gambling expenditure/net losses ($ billion) in Australia, by product, 2001–02 to 2019–20

This interactive data visualisation shows real gambling expenditure/net losses in $billions (Australian dollars) annually from 2001-02 to 2019-20, overall and by gambling product. Total gambling expenditure/losses increased over time up until 2019-20 when the COVID-19 restrictions in Australia (March-May 2020) resulted in the shutdown of land-based gambling. Prior to the COVID-19 restrictions gambling expenditure/net losses had been decreasing for gaming/poker machines and casinos, and increasing for wagering (racing, sports, and other events).

Notes

- Expenditure data (that is, the net amount lost or the amount wagered less the amount won by people who gamble) should be read in conjunction with the explanatory notes in the Australian Gambling Statistics (AGS) report.

- All jurisdictions, except Western Australia, have a state-wide gaming (poker) machine network operating in clubs and/or hotels. ‘Gaming machines’ does not include gaming/poker machine data from casinos.

- ‘Wagering’ includes all legal forms of gambling on racing, sporting events and other approved events (e.g., elections). As a result of the introduction of point of consumption tax and subsequent changes to the way wagering data are collected, detailed breakdowns for ‘Wagering’ are no longer reported in AGS as of 2019–20 and represent a break in series for all states and territories. Wagering expenditure data in 2019–20 for the Northern Territory was estimated for residents only and is not comparable to previous years.

- ‘Casino’ represents wagers at casinos and includes wagers on table games, gaming machines and keno systems.

- ‘Lotteries’ includes lotteries, lotto, pools and instant scratchies. In June 2018, pools was withdrawn from the Australian lottery market.

- ‘Keno’ is a game where a player wagers that their chosen numbers match any of the 20 numbers randomly selected from a group of 80 numbers via a computer system or a ball-draw device.

- ‘Other Gaming’ includes Minor Gaming (Western Australia only - raffles, bingo, lucky envelopes and the like) and Interactive Gaming (Northen Territory only - gambling on activities conducted via the internet, excluding wagering in the form of racing and sports betting, keno and lotteries via the internet).

- The 2019–20 financial year was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions and these data should be read in conjunction with the explanatory notes in the Australian Gambling Statistics report.

Source: QGSO 2022.

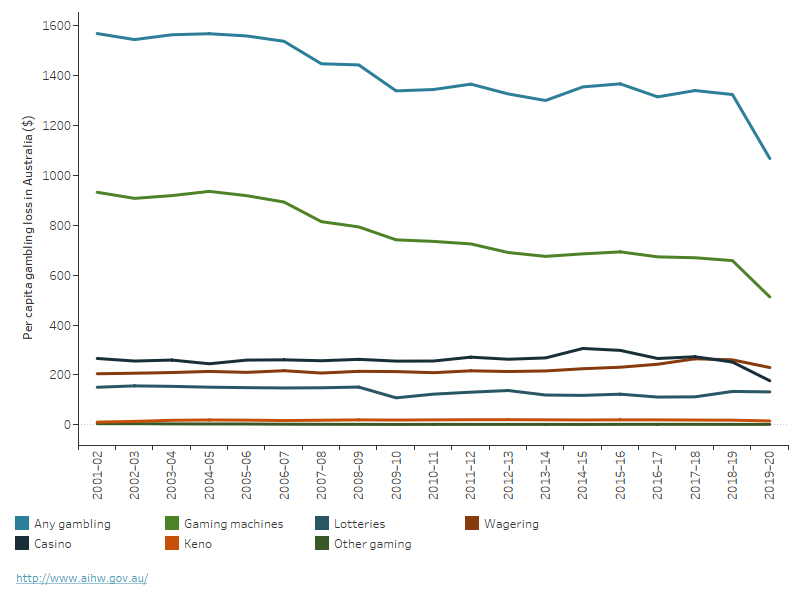

In 2019–20, per capita gambling expenditure/losses in Australia were estimated at around $1,068, down from $1,324 in 2018–19 (Figure 5). Over time, per capita expenditure on poker machines has been declining (although it still accounts for the most losses), while per capita expenditure on wagering (races, sports, other events) has been increasing.

Figure 5: Per capita real gambling expenditure/net losses in Australia, by product, 2001–02 to 2019–20

This interactive data visualisation shows per capita expenditure for any gambling has decreased over time, mainly due to a decrease in per capita expenditure on poker machines. Per capita expenditure on other gambling activities has generally remained stable or been increasing (e.g. wagering) over time (with the exception of 2019-20 which was impacted by the COVID-19 restrictions).

Notes

- Per capita calculations are undertaken by dividing the relevant data for a given financial year by the mean resident population aged 18 and over in the region during the relevant financial year.

- Wagering expenditure data in 2019–20 for the Northern Territory was estimated for residents only and is not comparable to previous years.

- The 2019–20 financial year was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions and these data should be read in conjunction with the explanatory notes in the Australian Gambling Statistics report.

Source: QGSO 2022.

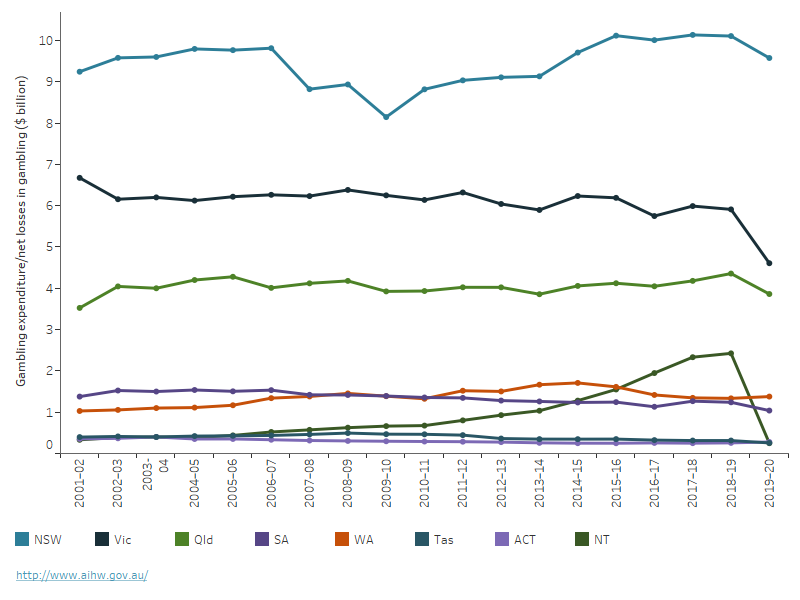

Total gambling expenditure/losses remain highest in the most populated states and territories in Australia (Figure 6). For example, estimates suggest that New South Wales recorded the highest expenditure ($9.6 billion or $1,508 per capita), followed by Victoria ($4.6 billion or $882 per capita), and Queensland ($3.9 billion or $977 per capita).

Availability of gambling, when measured in total number of poker machines, for example, is also highest in these states:

- New South Wales (91,675 machines; equivalent to around 48% of Australia’s machines)

- Queensland (44,918; 24%)

- Victoria (29,404; 15%).

Figure 6: Total real gambling expenditure/net losses ($ billion), by state and territory, 2001–02 to 2019–20

This interactive data visualisation shows real gambling expenditure/net losses in $billions (Australian dollars) annually from 2001–02 to 2019–20, by Australian state/territory. The 3 most populated states in Australia, which also have the highest number of poker machines, have the highest gambling expenditure/losses (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland). The increasing trend in gambling expenditure in the Northern Territory up until 2018-19 was largely due to the increase in wagering providers being licensed in that territory (2019-20 cannot be compared to previous years for the NT as it was estimated for residents only).

Notes

- Caution should be used when comparing data between states and territories as each jurisdiction has its own data collection systems, processes and reporting methods. Gambling regulation also differs across jurisdictions; for example, most wagering providers in Australia are registered in the Northern Territory and this accounts for the growing proportion of national expenditure in that jurisdiction up until 2018–19. The wagering expenditure data in 2019–20 for the Northern Territory was estimated for residents only and is not comparable to previous years.

- There have been changes in point of consumption (POC) tax for wagering by state/territory. The Northern Territory is the only jurisdiction not to include POC tax and the 2019–20 data is not able to be compared to previous years’ data.

- Figures may be incomplete for any period or jurisdiction due to unavailable expenditure data.

- The data for each individual state/territory include expenditure generated by residents of that state/territory as well as by interstate and overseas visitors.

- The 2019–20 financial year was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions and these data should be read in conjunction with the explanatory notes in the Australian Gambling Statistics report.

Source: QGSO 2022.

Gambling-related harm

Measuring gambling-related harm among people who gamble

Gambling-related harm is commonly assessed via the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI). The PGSI provides a measure of at-risk gambling behaviour during the previous 12-month period.

It consists of 9 items (questions), such as ‘have you bet more than you could really afford to lose?’, with response options being never (0), sometimes (1), most of the time (2) and almost always (3).

Scores are summed for a total between 0 and 27.

Respondents are grouped into 4 categories based on their scores:

- non-‘problem’/non-risk gambling (0)

- low-risk gambling (1–2)

- moderate-risk gambling (3–7)

- ‘problem’/high-risk gambling (8–27).

Respondents scoring 1+ may be classified as being at some risk of, or already experiencing, gambling-related harm (Ferris and Wynne 2001).

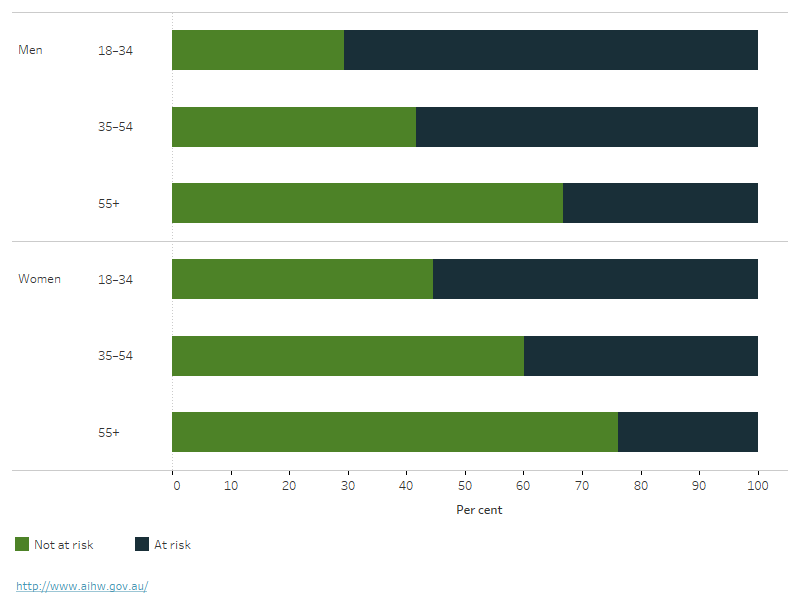

Research conducted in 2022 found that almost half (46%) of Australians aged 18 and over who gambled would be classified as being at-risk of, or already experiencing, gambling harm (low, moderate, or high-risk PGSI categories combined).

Differences were observed by gender and age group, with a greater proportion of men who gambled being classified as at-risk of harm (53% for men and 38% for women). At-risk gambling was highest in 18–34-year-olds among both men (71%) and women (56%) (AGRC 2023; Figure 7).

Figure 7: Levels of at-risk gambling among Australian adults who gamble, by age and gender, 2022

This interactive data visualisation shows the proportion of Australian adults who gamble who would be classified as being at-risk of gambling harm (as measured the Problem Gambling Severity Index; PGSI score 0 = not at-risk gambling; 1+ = at-risk gambling). A greater proportion of men than women across all age groups (18-34, 35-54, 55+ years) were classified as being at-risk of gambling harm. At-risk gambling was highest among the youngest age group (18-34 years) for both men and women.

Note: Sample analysed consisted of n=1,282 Australian residents aged 18 years and over who had gambled in the past 12 months.

Source: Community Attitudes Survey (Australian Gambling Research Centre 2023).

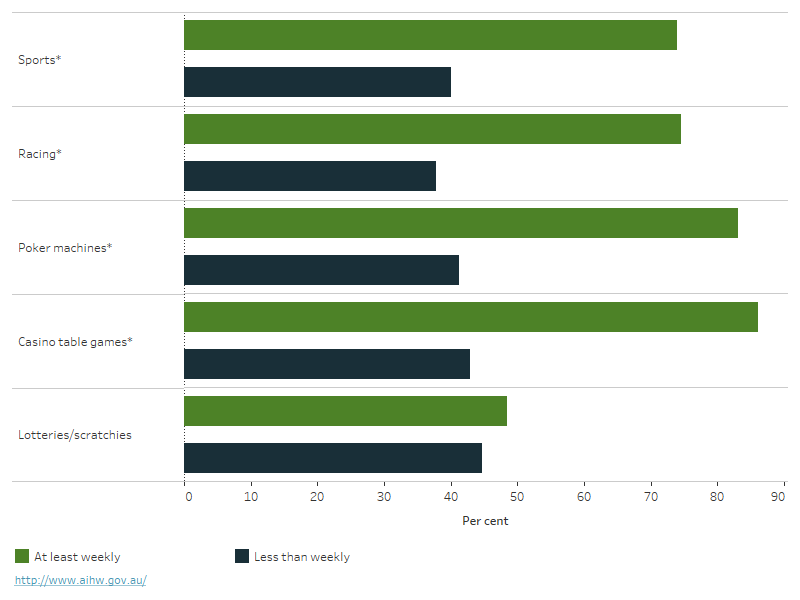

Adults (aged 18 and over) who engaged in regular (at least weekly) gambling on sports, racing, poker machines and casino tables games were significantly more likely to be classified as being at-risk of harm than those gambling less than weekly (Figure 8).

Figure 8: At-risk gambling among Australian adults who gamble, by product and frequency (less than weekly, at least weekly), 2022

This interactive data visualisation shows differences in at-risk gambling among Australian adults who gamble, by product and frequency (less than weekly, at least weekly). At-risk gambling was significantly higher for those gambling more frequently on sports, racing, poker machines, and casino table games – but not lotteries/scratchies.

Notes

- Sample analysed consisted of n=1,287 Australian residents aged 18 years and over who had gambled in the past 12 months.

- *Statistical difference between groups is significant at the p<.05 level.

Source: Community Attitudes Survey (Australian Gambling Research Centre 2023).

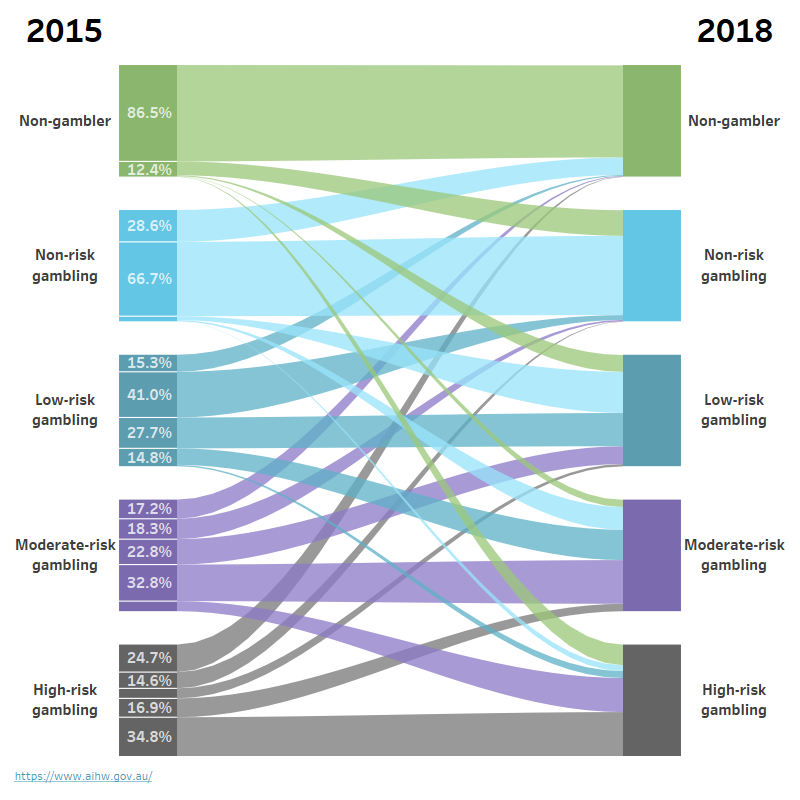

Longitudinal data from the nationally representative Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey highlights how an individual’s at-risk gambling behaviour and experience of harm can change over time. For example, analysis of PGSI data from Wave 15 (in 2015) and Wave 18 (in 2018) found that:

- around 1 in 3 participants (35%) who were classified in the high-risk category in 2015 remained at this level 3 years later

- one-quarter (25%) who were classified in the high-risk category had ceased gambling and around 40% decreased their level of at-risk gambling

- around 16% who were categorised as low-risk gambling in 2015 gambled at more harmful levels 3 years later (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Changes in at-risk gambling among Australian adults who gamble, 2015 and 2018

This figure shows changes in at-risk gambling between 2015 and 2018 among a cohort of Australian adults who gambled. Levels of at-risk gambling were assessed using the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI score 0 = non-risk gambling; 1-2 = low-risk gambling; 3-7 = moderate-risk gambling; 8+ = high-risk gambling). Green cells show a decrease in at-risk gambling, yellow cells show stable at-risk gambling levels, and orange cells show an increase in at-risk gambling level.

Notes

- Only the respondents who answered all 9 PGSI items in Wave 15 and 18 (n = 12,156) are included in the estimation. Sample sizes by PGSI group: non-gambler (n = 7,234); non-risk gambling (n = 4,153); low-risk gambling (n = 412); moderate-risk gambling (n = 268); high-risk gambling (n = 89).

- Estimations use the SCQ weighting values provided in the HILDA survey dataset.

- Guide to highlighted cells in table: green = from 2015 to 2018 at-risk level decreased; yellow = from 2015 to 2018 at-risk level stayed the same; orange = from 2015 to 2018 at-risk level increased.

Sources: HILDA Wave 15 2015, HILDA Wave 18 2018. AIFS’ calculation.

Types of gambling-related harm

Gambling-related problems and harm can be experienced on a spectrum, ranging from lower-level negative experiences or general harms (such as reduced performance due to tiredness or distraction, relationship conflict, impacts on health and wellbeing and erosion of savings) to crisis harms (where immediate support is needed) and legacy harms (occurring sometime after gambling has ceased) (see glossary).

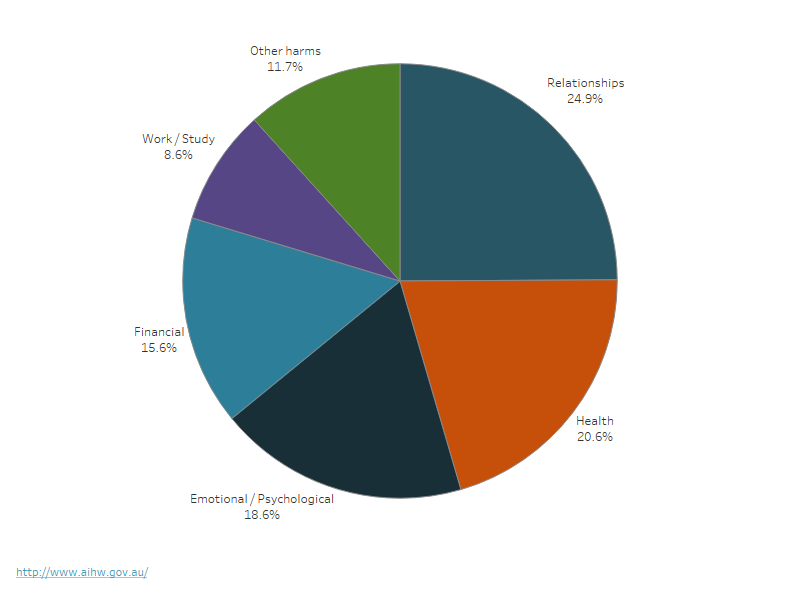

Browne and colleagues (2016) developed a conceptual framework for gambling-related harm that comprises 7 main domains: financial, relationships, emotional/psychological, decrements to health, reduced performance at work/study, and cultural harm and criminal activities (combined below as ‘other harms’).

Estimates of the distribution of harm across these domains are presented in Figure 10. Harms to relationships (25%), health (21%), and emotional/psychological wellbeing (19%) accounted for the greatest share of gambling-related harm.

Figure 10: Distribution of gambling-related harm by domain

This pie chart shows estimates of the distribution of gambling-related harm by domain, including harms to relationships (24.9%), health (20.6%), and emotional/psychological wellbeing (18.7%), financial (15.6%), other harms (11.7%), and work/study (8.6%).

Gambling and its impact on others

In recent years, it has been increasingly recognised that gambling-related harms affect not only people who gamble, but also their families, friends, and the wider community (see, for example, Browne et al. 2016, Dowling 2014, Goodwin et al. 2017, Hing et al. 2020, Langham et al. 2016, and Wardle et al. 2018).

Research conducted by Goodwin and colleagues (2017) examined how many people (on average) could be negatively affected by someone else’s at-risk gambling. The research found that a person experiencing problem gambling can affect up to 6 other people around them, moderate-risk gambling up to 3 others, and low-risk gambling up to one other. Close family members, including spouses and children, were most often identified as the people impacted by others’ gambling problems (Goodwin et al. 2017).

The National Telephone Survey of the 2019 Interactive Gambling Study asked a representative sample of Australian adults whether they had been personally and negatively affected by another person’s gambling in the past 12 months (Hing et al. 2021). Overall, 6.0% reported being harmed by someone else’s gambling. Those most commonly affected were family members (including spouses/partners, other relatives, siblings, former spouse/partners), friends, and work colleagues. The most common harms experienced due to another person’s gambling were feeling angry, distressed or hopeless about their gambling, and experiencing greater tension and conflict in their relationships. Reduction of available spending money or savings, loss of sleep and less enjoyment from time spent with people they care about were also commonly reported.

Gambling-related help seeking

State and territory prevalence studies suggest that a very small proportion of people seek help for gambling-related harms. For example, the most recent New South Wales gambling survey found that just under one per cent (0.9%) of people who gamble had sought help for harms related to their gambling in the past 12 months.

Estimates of help seeking in other states and territories were similar: 1.0% in Tasmania; 1.5% in the Northern Territory and 2% in the Australian Capital Territory (Browne et al. 2019; Menzies School of Health Research 2019; O’Neil et al. 2021; Paterson et al. 2019). Among those who did seek help, the strategies used included talking with friends or family and accessing services such as Gambling Helplines.

Support services are available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week:

Emerging gambling trends

The National Gambling Trends Study was developed to improve understanding of current and emerging trends in gambling and related harm in Australia, and areas for future policy and practice focus. The study includes surveys of people who gamble regularly (at least fortnightly) on land-based pokies and/or online on sports or wagering, and interviews with key experts in gambling policy, regulation, treatment, and consumer advocacy.

In 2022 participants described a range of emerging trends in gambling that they had observed, including (AGRC 2023):

- an increase in exposure to gambling marketing, including advertising (for example, television, social media), promotions and incentives (for example, multi-bets, bonus bets, cash back offers, bet with mates), and sponsorships (for example, promotion of sports, by celebrities or athletes)

- an increase in online gambling and concern about the potential harms due to factors such as the widespread availability and ease of access, new onshore and offshore gambling operators and products (for wagering and online pokies/casino products), and limited consumer protections or monitoring of people who might be at risk of harm

- increased spending on poker machines post-COVID-19 restrictions and concern about the widespread availability of pokies in the community and the increased ‘addictiveness’ of the machines with offers such as linked jackpots and increases in minimum machine denominations

- convergence of video gaming and gambling through products that are appealing to young people, including simulated gambling games, loot boxes, and in-game purchases

- an overall increase in gambling-related harm in Australia and concerns about the normalisation of gambling for youth, increases in youth gambling and risk of harm.

Data gaps and opportunities for improved gambling monitoring

Globally, gambling has expanded at a rapid pace in recent decades with new technologies and emerging products, and related harms are an increasing concern. This page draws on available data to describe trends in gambling participation, expenditure and related harms in Australia; however, there are limitations to these data sources (including a lack of consistency in study design, sample selection and measurement of gambling consumption and harm). A continuing, cost-effective system for monitoring gambling consumption and related harms is needed.

The Australian Gambling Research Centre is conducting the National Gambling Trends Study to better inform and support evidence-based policy and practical responses. The national system will enable the collection of regular, comprehensive and standardised data – within and across Australian jurisdictions – on trends in gambling consumption among people who gamble, experience of related harms and help-seeking behaviours, and emerging issues warranting further in-depth investigation. See the Gambling Trends Study for further details.

Further investment in a national gambling prevalence study and longitudinal research programs would provide representative population-level data on the prevalence and patterns of different gambling behaviours in Australia, allowing changes in the extent and nature of gambling and related harms to be assessed over time and policy and practical initiatives to be evaluated.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on gambling, please see:

- Australian Gambling Research Centre Gambling participation, experience of harm and community views

- Australian Institute of Family Studies Gambling in Australia during COVID-19

- Australian Institute of Family Studies The link between video games and gambling

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts Harms associated with loot boxes, simulated gambling and other in-game purchases in video games

- National Gambling Trends Study (Gambling Trends Study).

Acknowledgements

The Australian Gambling Research Centre was established under the Gambling Measures Act 2012 (Cwth). The Centre’s gambling research program reflects the Act, embodies a national perspective and has a strong family focus. It is part of the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) and the authors wish to greatly acknowledge the AIFS for supporting this work. Special thanks go to the AIHW for guidance and assistance in producing this page, and to the Department of Social Services and Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation for providing expert review. We are very grateful to the data custodians and research participants for their valuable contributions to this work.

Contact the Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies, [email protected].

ACMA (Australian Communications and Media Authority) (2022) Online gambling in Australia: Findings from the 2021 ACMA annual consumer survey, ACMA, Australian Government, accessed 23 May 2023.

AGRC (Australian Gambling Research Centre) (2023) Gambling participation, experience of harm and community views: An overview, AGRC, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, accessed 23 May 2023.

Biddle N (2020) Gambling during the COVID-19 pandemic, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, accessed 23 May 2023.

Browne M, Goodwin BC and Rockloff MJ (2018) ‘Validation of the Short Gambling Harm Screen (SGHS): A Tool for Assessment of Harms from Gambling’, Journal of Gambling Studies, 34:499–512, doi:10.1007/s10899-017-9698-y.

Browne M, Greer N, Armstrong T, Doran C, Kinchin I, Langham E and Rockloff M (2017) The social cost of gambling to Victoria, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, accessed 23 May 2023.

Browne M, Langham E, Rawat V, Greer N, Li E, Rose J, Rockloff M, Donaldson P, Thorne H, Goodwin B, Bryden G and Best T (2016) Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: a public health perspective, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, accessed 23 May 2023.

Browne M, Rockloff M, Hing N, Russell AM, Boyle CM, Rawat V, Tran K, Brook K and Sproston K (2019) NSW Gambling Survey 2019, NSW Responsible Gambling Fund, accessed 23 May 2023.

Dowling N (2014) The impact of gambling problems on families, Australian Gambling Research Centre discussion paper, Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies, accessed 23 May 2023.

Ferris J and Wynne H (2001) The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: final report. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, Canadian consortium for gambling research, accessed 23 May 2023.

Greer N, Murray Boyle C and Jenkinson R (2022) Harms associated with loot boxes, simulated gambling and other in-game purchases in video games: a review of the evidence, Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, accessed 23 May 2023.

Goodwin BC, Browne M, Rockloff M and Rose J (2017) ‘A typical problem gambler affects six others’, Journal of Gambling Studies 17(2):276–89.

Hing N, Gainsbury S, Blaszczynski A, Wood R, Lubman D, and Russell A (2014) Interactive Gambling, Gambling Research Australia, doi:10.13140/2.1.1381.6648.

Hing N, O’Mullan C, Nuske E, Breen H, Mainey L, Taylor A, Frost A, Greer N, Jenkinson R, Jatkar U, Deblaquiere J, Rintoul A, Thomas A, Langham E, Jackson A, Lee J and Rawat V (2020) The relationship between gambling and intimate partner violence against women, Research report, 21/2020, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety Limited, accessed 23 May 2023.

Hing N, Russell AMT, Browne M, Rockloff M, Greer N, Rawat V, Stevens M, Dowling N, Merkouris S, King D, Breen H, Salonen A and Woo L (2021) The second national study of interactive gambling in Australia (2019–20), Gambling Research Australia.

Jenkinson R, Sakata K, Khokhar T, Tajin R and Jatkar U (2020) Gambling in Australia during COVID‑19, Australian Gambling Research Centre, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, accessed 23 May 2023.

Langham E, Thorne H, Browne M, Donaldson P, Rose J and Rockloff M (2016) Understanding gambling related harm: a proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms, BMC Public Health 16:1–23.

Letts S (2018) Chart of the day: Are Australians the world’s biggest gambling losers? You can bet on it, ABC News, 20 November, accessed 23 May 2023.

Menzies School of Health Research (2019) Northern Territory 2018 Gambling Prevalence and Wellbeing Survey Report, Northern Territory Government website, accessed 23 May 2023.

O’Neil M, Whetton S, Kosturjak A, Hancock J, Dey T, Delfabbro P, Sproston K, Wittwer G and Eslake S (2021) Fifth Social and Economic Impact Study of Gambling in Tasmania 2021. Volume 2: 2020 Prevalence Survey Report,South Australian Centre for Economic Studies, accessed 23 June 2023.

Paterson M, Leslie P and Taylor M (2019) 2019 ACT Gambling Survey, Australian National University Centre for Gambling Research, accessed 23 May 2023.

QGSO (Queensland Government Statistician’s Office), Queensland Treasury (2022) Australian gambling statistics, 37th edition Australian gambling statistics, 37th edition 1994–95 to 2019–20, Queensland Treasury, accessed 23 May 2023.

Tajin R, Quinn B, Wong C, O’Donnell K, Rowland B, Prattley J and Jenkinson R (2022) Gambling participation and harm among Australian men. In B. Quinn, B. Rowland, & S. Martin (Eds.), Insights #2 report: Findings from Ten to Men – The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health 2013–21, Australian Institute of Family Studies website, accessed 23 May 2023.

Sakata K and Jenkinson R (2022) What is the link between video gaming and gambling? (Growing Up in Australia Snapshot Series, Issue 7), Australian Institute of Family Studies website, accessed 23 May 2023.

Wardle H, Reith G, Best D and McDaid D (2018) Measuring gambling-related harms. A framework for action, Gambling Commission, accessed 23 May 2023.