Employment of First Nations people

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Employment of First Nations people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Employment of First Nations people. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-employment

MLA

Employment of First Nations people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-employment

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Employment of First Nations people [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-employment

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Employment of First Nations people, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/indigenous-employment

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Employment lies at the heart of socioeconomic opportunity. It provides direct economic benefit to individuals and families, including financial security, increased social mobility and access to higher standards of living. Beyond this, it is well established that working is associated with benefits to physical and mental health, social inclusion and improved developmental outcomes for the children of employed persons (Biddle 2013; Gray et al. 2014; WHO 2016).

This page provides an overview of employment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people over time.

See Income and finance of First Nations people for more information on the household and personal income of First Nations people (including wages and salaries from employment).

Closing the Gap targets

In 2020, all Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations worked in partnership to develop the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement), built around 4 Priority Reforms. The National Agreement also identifies 19 targets across 17 socioeconomic outcome areas. Two of these targets directly relate to employment.

National Agreement on Closing the Gap: employment-related targets

Outcome area 7: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth are engaged in employment or education

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth (15–24 years) who are in employment, education or training to 67 per cent.

- Status: The 2016 baseline of Indigenous youth who are in employment, education or training was 57.2%. The most recent level, using data from 2021, is 58.0%. This is below the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 60.5%.

Outcome area 8: Strong economic participation and development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities

- Target: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 25–64 who are employed to 62 per cent.

- Status: The 2016 baseline for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people was 51.0%. The most recent level, using data from 2021, is 55.7%, higher than the target trajectory proportion for 2021 of 54.7%.

Note that data for these targets were derived from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census of Population and Housing (Census) (ABS 2021; PC 2021).

Prior to establishment of the National Agreement, there were 7 Closing the Gap targets set by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, one of which was to halve the gap in employment rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians between 2008 and 2018. The Closing the Gap Report 2020 found that this target expired unmet.

Overview of First Nations people’s employment status

The 2021 Census, conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), provides the most recent data on employment of First Nations people. For those aged 25–64 (the age group specified in Target 8 of the National Agreement), the employment rate (the proportion of people who are employed) was 56% in 2021 (ABS 2021).

For the rest of this page, employment data are presented for First Nations people aged 15–64, as this is generally considered to represent ‘working age’. Between July 2017 and July 2023, the age a person becomes able to receive Age Pension was gradually increased from 65 to 67 years (see Income support for older Australians). This may lead to increased employment among people of this age. On this page, however, data are shown for people aged 15–64 for consistency with previous reporting and for comparability over the reporting period (2006 to 2021). In 2021, 26% of First Nations people aged 65–67 were employed, compared with 21% in 2016.

Labour force definitions

This page presents information on the number of First Nations people who are employed, unemployed or not in the labour force, as a proportion of the First Nations population aged 15–64. While the age when a person is eligible for the Age Pension has increased to 67, this report still uses ages 15–64 for consistency with previous reporting and comparisons across the reporting period. The following definitions are used:

Employed: Person aged 15–64 who has a job (for at least 1 hour during the reference period). This could be full time, part time, or away from work during the reference period.

Unemployed: Person aged 15–64 who does not have a job and is actively looking for one. This could be looking for a full or part time job.

The sum of employed and unemployed is the number of people in the labour force.

Not in the labour force: Person aged 15–64 who is not employed and not actively looking for work during the reference week of the Census. This definition applies to the Census and may differ somewhat from the definitions in other collections.

Note that ‘proportion unemployed’ as reported on this page is not the same as the ‘unemployment rate’ presented elsewhere. The unemployment rate is calculated as the number of people who are unemployed divided by the number of people in the labour force – that is, the denominator excludes people who are not in the labour force. The unemployment rate for First Nations people in 2021 was 12% (ABS 2021).

In 2021:

- a similar proportion of First Nations males and females aged 15–64 were employed (53% and 51%)

- a higher proportion of males than females were unemployed (8.3% compared with 6.5%)

- a lower proportion of males than females were not in the labour force (38% compared with 42%).

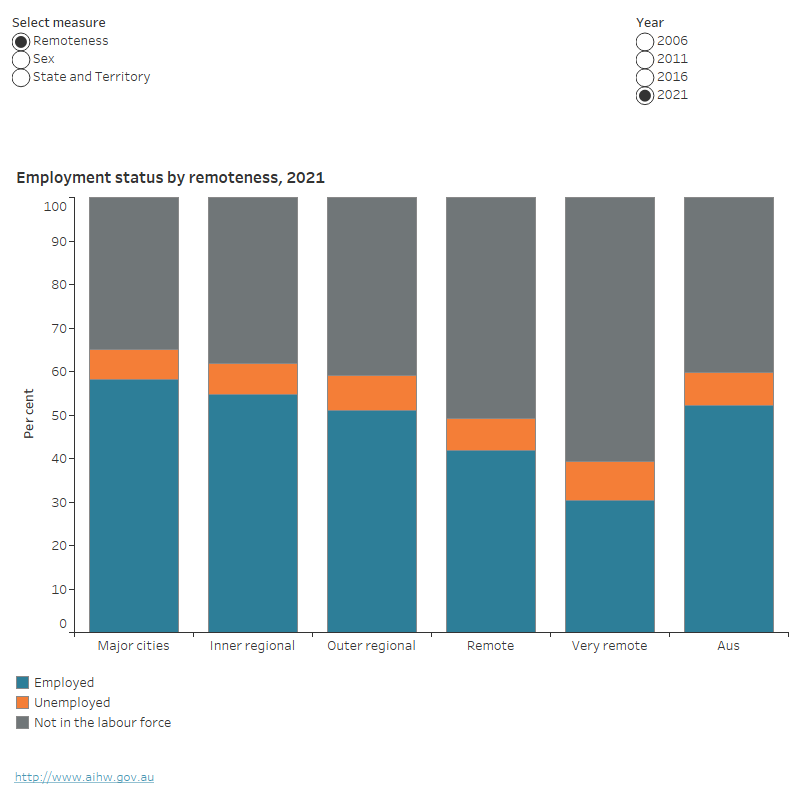

Figure 1: First Nations people aged 15–64 by employment status 2006 to 2021

This visualisation shows the proportion of First Nations people aged 15–64 years who are employed, unemployed, or not in the labour force by remoteness for the 2021 Census. A higher proportion of First Nations people are employed in Major cities (58%) and lowest in Very remote areas (30%). A similar proportion of First Nations males and females aged 15–64 were employed (53% and 51%). Employment was highest in the Australian Capital Territory (69%), followed by Tasmania (59%), and lowest in the Northern Territory (31%). Similar patterns for remoteness and state or territory are found in every Census back to 2006. The difference between male and female employment has narrowed over time.

Note: People whose employment status was not stated and those whose remoteness or state/territory is outside of the categories listed are excluded from the proportions.

Sources: AIHW analysis of ABS 2006, 2011, 2016, 2021.

Interpreting changes over time

The Commonwealth Development Employment Projects (CDEP) was an employment assistance program established in 1977 to create employment opportunities in remote communities by pooling unemployment benefits. Assessing First Nations employment trends is complicated by the many changes in the coverage – and subsequent re-branding and closure in 2013 – of the CDEP, as well as changes in whether participants were considered to be ‘employed’ for the purposes of labour force data collection. For more information, see section 4.7 of Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2020.

Employment

Employment by location

In 2021, the proportion of First Nations people who were employed decreased consistently with increasing remoteness, from 58% in Major cities to 30% in Very remote areas. This pattern is consistent with that of data for 2011 and 2016; however, in 2006, Outer regional areas had the lowest proportion employed (Figure 1). In contrast, the proportion of non-Indigenous Australians who are employed does not decrease with remoteness (PMC 2020).

The proportion of First Nations people employed in 2021 also varied markedly by state and territory. It was highest in the Australian Capital Territory (69%), followed by Tasmania (59%), and lowest in the Northern Territory (31%). This pattern has remained roughly the same since 2006.

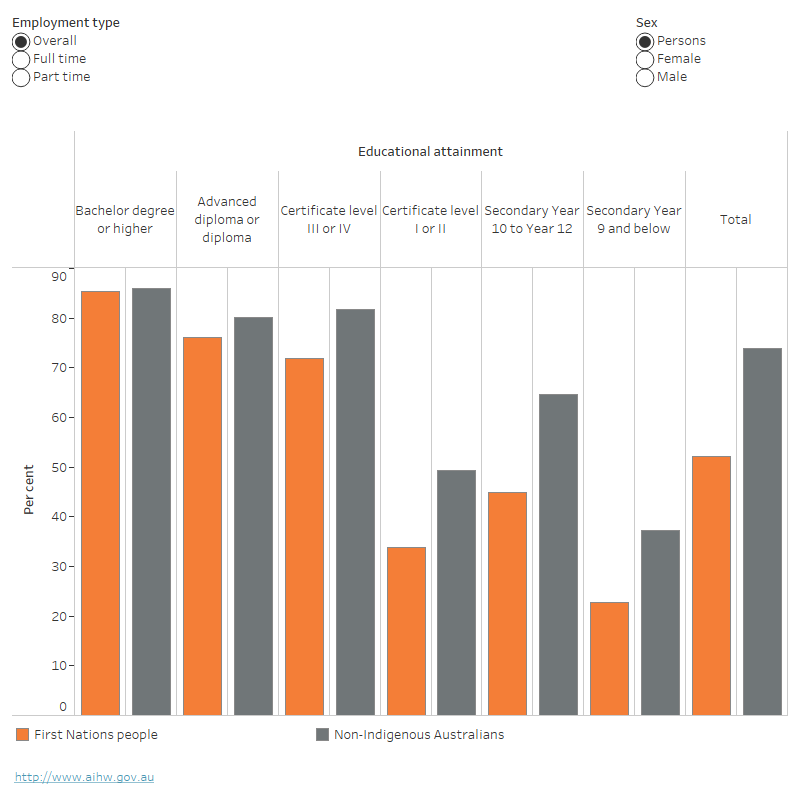

Employment by education level and sex

The employment rate of First Nations people has consistently shown an increase with higher levels of education. In 2021, the observed employment rate pattern relative to the highest level of education completed was:

- 85% for those with a Bachelor degree or higher

- 72% for those with a Certificate III or IV

- 45% for those with secondary year 10 to year 12

- 23% for those with secondary year 9 and below (Figure 2).

This pattern is reasonably consistent across age groups.

The full-time employment rate (the proportion of people of workforce age who are employed full time) for First Nations people was 29% in 2021, and the pattern of full-time employment by education level was similar to that for the overall employment rate: those with a Bachelor degree or higher had the highest full-time employment rate (58%) and those with secondary year 9 and below had the lowest (9%) (Figure 2).

The overall part-time employment rate was 17% in 2021 for First Nations people; however, a slightly different pattern emerged when viewed by education level. The part-time rate was highest for those with an Advanced diploma or Diploma (22%), and again lowest for those with secondary year 9 and below (10%) (Figure 2).

In 2021, the gap in the employment rate between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians narrowed with higher levels of education. Overall, non-Indigenous Australians had a higher rate of employment for all education levels, although for a Bachelor degree or higher this narrowed to a difference of 0.6 percentage points.

The exception was for females with a Bachelor degree or higher. In this group:

- First Nations females had a higher overall employment rate by 1.8 percentage points

- First Nations females had a higher full-time employment rate than non-Indigenous females, with a gap of 5.4 percentage points

- Non-Indigenous females had a higher part-time employment rate than First Nations females, with a gap of 4.6 percentage points.

Employment rates for First Nations people in 2021 differed by sex. Males had a higher overall employment rate (53%) than females (51%), and this difference was consistent across all levels of educational attainment except for the Bachelor degree or higher, with females having a higher employment rate (Figure 2). The biggest gap in employment rate between males and females was at the Certificate I/II level at 12 percentage points, with males higher than females (41% and 28%). The smallest gap was at the Bachelor degree level at 1 percentage point higher for females than males (86% and 85%).

Across all educational attainment levels, part-time employment rates for First Nations people were higher among females than males, and full-time employment rates were higher among males than females (Figure 2).

For more information on this topic see Education of First Nations people.

Figure 2: Proportion of employed people aged 15–64, by employment type, sex, Indigenous status and highest level of education, 2021

This visualisation shows the proportion of persons aged 15–64 years who are employed by Indigenous status and their highest level of educational attainment for the 2021 Census. Employment rates for First Nations people were highest for those with a Bachelor degree or higher (85%), and lowest for those with secondary Year 9 and below (23%). This pattern was consistent with overall employment and full time employment regardless of sex. The highest employment for part time employment was among those with an advanced diploma or diploma for males and a Certificate level III or IV for females. The gap between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians was largest for those with secondary Year 10 to Year 12 education (20 percentage points).

Note: ‘Employed but away from work’ is included in the ‘Overall’ employment type, but is excluded from the ‘Full-time’ and ‘Part-time’ employment types due to unknown data.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2021.

Employment by sector

In 2021, just over 10% of First Nations people aged 15–64 were employed in the public sector, that is, by federal, state, territory or local governments. Just over 41% of First Nations people were employed in the private sector. The gap in the public sector employment rate was less than 2 percentage points (10.4% for First Nations people compared with 12.0% for non-Indigenous Australians), while the gap in private sector employment was much greater at 21 percentage points (41.2% compared with 62.4%) (ABS 2021).

Main occupations and industries of employment

This section provides 2 types of information about employed First Nations people:

- their occupation (in high-level groupings); the type of job they do

- their industry of employment; the main type of activity their employer undertakes.

For example, a person who works as an accounts clerk for a major clothing store would have ‘clerical and administrative workers‘ as their occupation group and ‘retail trade’ as their industry of employment.

Main occupation groups

The 5 most common occupation groups of working age First Nations people in 2021 were:

- community and personal service workers (17%)

- labourers (14%)

- professionals (14%)

- technicians and trades workers (14%)

- clerical and administrative workers (12%) (Figure 3; ABS 2021).

In 2021, First Nations people were over-represented in labouring and community and personal service occupations. First Nations people were under-represented as professionals and managers, relative to the working age non-Indigenous population – 14% of working age non-Indigenous Australians were managers compared with 8% of First Nations people (ABS 2021).

First Nations people who worked part time were most likely to be employed as community and personal service workers (24%), labourers (19%) or sales workers (16%), whereas those who worked full time were most likely to be employed as technicians and trades workers (18%), professionals (16%) or clerical and administrative workers (13%) (ABS 2021).

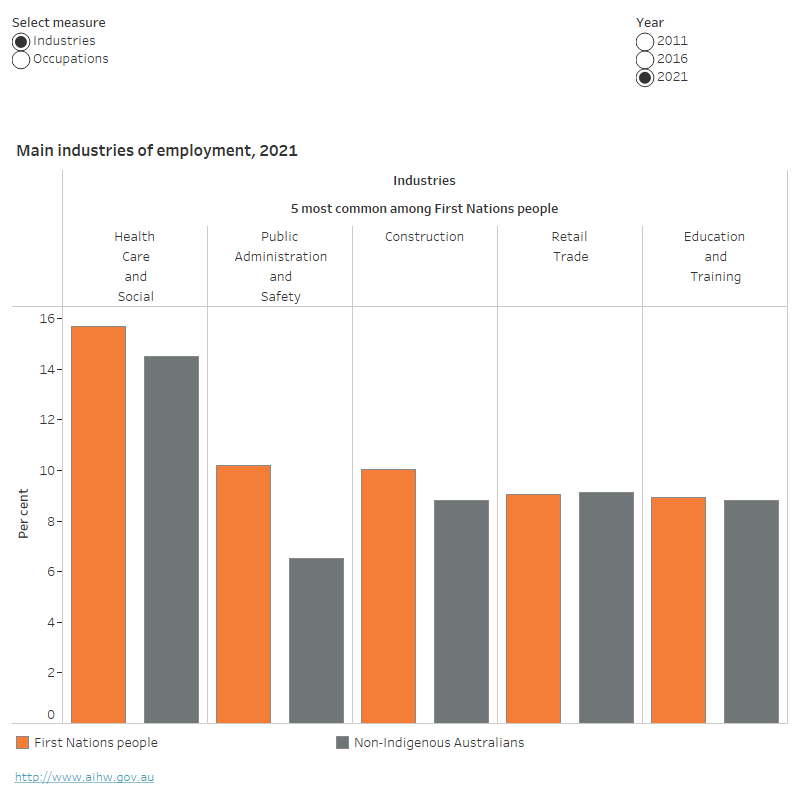

Main industries of employment

The 5 most common industries of employment for working age First Nations people in 2021 were:

- health care and social assistance (16%)

- public administration and safety (10%)

- construction (10%)

- retail trade (9.1%)

- education and training (8.9%) (Figure 3; ABS 2021).

Between 2016 and 2021, the proportion of First Nations people employed in health care and social assistance increased while the proportion employed in public administration and safety decreased (Figure 3).

In 2021, First Nations people were over-represented in the public administration and safety sector, and were under-represented in the professional, scientific and technical services sector. Only 3.2% of First Nations people were employed in the professional, scientific and technical services sector compared with 8.0% of non-Indigenous Australians (ABS 2021).

Among First Nations people employed part time, the retail trade and accommodation & food services industries were among the top 5 industries of employment, accounting for 16% and 14% of workers, respectively; this was also the case for non-Indigenous Australians (14% and 12% of workers). Health care and social assistance was the most common industry of employment for part-time workers in both groups (19% of First Nations people and 20% of non-Indigenous Australians) (ABS 2021).

Figure 3: Occupations and industries of employment, First Nations people aged 15–64, 2011, 2016 and 2021

This visualisation shows the 5 most common employment sectors of employed persons aged 15–64 years for First Nations people for the 2011 to 2021 Census. The most common employment sectors for First Nations people in 2021 were Health Care and Social Assistance (16%), Public Administration and Safety (10%), Construction (10%), Retail trade (9%) and Education and Training (9%). The most common occupations were Community and Personal Service (17%), Labourers (14%), Professionals (14%), Technicians and Trades Workers (14%) and Clerical and Administrative Workers (12%). Alternate views are presented from the previous Census in 2011 and 2016.

Sources: AIHW analysis of ABS 2021; PC 2020.

Unemployment

In 2021, 7.4% of First Nations people aged 15–64 were unemployed. This has decreased from a high of 10.5% in 2016. Unemployment varies between males and females. In 2021, more males were unemployed than females (8.3% and 6.5% respectively).

Western Australia and South Australia had the highest proportion of First Nations people unemployed, both with 8.8%. The Australian Capital Territory had the lowest unemployment rate with 5.4%.

In 2021, Very remote areas had a higher unemployment proportion with 8.9% compared with 6.9% in Major cities (Figure 1).

Not in the labour force

There are many reasons why a First Nations person may not be in the labour force. These include:

- lack of available and appropriate employment options

- cost associated with job searching

- need for further education or training for employment

- health concerns

- disability

- family responsibilities, including caregiving duties

- community responsibilities (Dinku and Hunt 2019; Hunter and Gray 2001; Kalb et al. 2014; Savvas et al. 2011).

In 2021, 40% of First Nations people of working age (15–64 years) were not in the labour force. This was slightly higher for females than males (42% and 38%, respectively).

The percentage of First Nations people not in the labour force ranged from 26% in the Australian Capital Territory to 61% in the Northern Territory. It also increased with increasing remoteness with 61% in Very remote areas compared with 35% in Major cities (Figure 1).

Impact of COVID-19

Although the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment in Australia has been substantial, there are few studies on the effect on the employment of First Nations people. However, some impacts may be inferred from differences between populations and characteristics of the First Nations workforce.

JobKeeper was a federal initiative that helped employees remain in jobs during the pandemic. To be eligible, a person needed to be employed in an ongoing position or have been in a job for more than 12 months (The Treasury 2020). First Nations workers are more likely to be in industries with more casual employees (Dinku et al. 2020). In addition, economic recessions often disrupt smaller sized businesses as they do not have the resources to withstand the pressures. First Nations-owned businesses are more likely to be small-medium sized business and employ more First Nations staff (Dinku et al. 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused many businesses to move to remote working, requiring a reliable home internet. In 2016, 75% of First Nations-only households had internet access, compared with 86% of non-Indigenous-only households (Hunter and Radoll 2020). If this ‘digital divide’ were to continue, exclusion from working remotely could be a risk to employment opportunities for First Nations people.

First Nations people have a relatively high proportion of people aged 15–24 among those of working age – in 2021, 30% of First Nations people of working age were 15–24, compared with 18% of non-Indigenous Australians (ABS 2021). Youth Allowance is a federal program that provides financial help for those aged 21 and under (or 24 and under if studying or undertaking an apprenticeship) while looking for a job or finishing study (Services Australia 2022). First Nations youth were more likely than non-Indigenous youth to be participating in youth allowance payments before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In December 2021, the rate of participation in youth allowance payments had decreased to pre-pandemic levels for non-Indigenous Australian youth but remained above pre-pandemic levels for First Nations youth (Dinku and Yap 2022).

Work hours and happiness with career prospects decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic for all youth, but more so for First Nations youth. The rate of transition from unemployment to employment between 2019 and 2020 was lower for First Nations youth than non-Indigenous Australian youth (Dinku and Yap 2022).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on employment among First Nations people, see:

- NIAA Closing the Gap Report 2020

- Productivity Commission Performance Reporting Dashboard on the National Indigenous Reform Agreement

- ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19

- National Agreement on Closing the Gap

- Productivity Commission Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2020.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2006) 2006 Census – Labour Force [TableBuilder], accessed 13 January 2023.

ABS (2011) 2011 Census – Employment, Income and Unpaid Work [TableBuilder], accessed 12 January 2023.

ABS (2016) 2016 Census – Employment, Income and Education [TableBuilder], accessed 12 January 2023.

ABS (2021) 2021 Census – Employment, Income and Education [TableBuilder], accessed 27 April 2023.

Biddle N (2013) ‘Socioeconomic Outcomes’, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, accessed 5 August 2021.

Dinku Y and Hunt J (2019) Factors Associated with the Labour Force Participation of Prime-age Indigenous Australians, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, accessed 6 June 2023.

Dinku Y, Hunter B and Markham F (2020) ‘Implications of COVID-19 for the Indigenous labour market', Supply Nation, accessed 18 January 2023.

Dinku Y and Yap M (2022) ‘Young Australians’ labour market engagement and job aspiration in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 00:1-19, doi:10.1002/ajs4.234.

Gray M, Hunter B and Biddle N (2014) The economic and social benefits of increasing Indigenous employment, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University, accessed 5 August 2021.

Hunter B and Gray M (2001) ‘Indigenous labour force status re-visited: Factors associated with the discouraged worker phenomenon’, Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 4(2):111-133.

Hunter BH and Radoll PJ (2020) ‘Dynamics of digital diffusion and disadoption: A longitudinal analysis of Indigenous and other Australians’, Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 24, doi:10.3127/ajis.v24i0.1805.

Kalb G, Le T, Hunter B and Leung F (2014) ‘Identifying important factors for closing the gap in labour force status between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians’, Economic Record, 90(291):536-550, doi:10.1111/1475-4932.12142.

PMC (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) (2020) Closing the Gap report 2020, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government, accessed 11 May 2023.

PC (Productivity Commission) (2020) Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2020, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 3 May 2023.

PC (2021) Dashboard | Closing the Gap Information Repository - Productivity Commission (pc.gov.au)Closing the Gap information repository: dashboard, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 12 January 2023.

Savvas A, Boulton C and Jepsen E (2011) Influences on Indigenous labour market outcomes, Staff working paper, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 3 May 2023

Services Australia (2022) Youth Allowance, Services Australia, Australian Government, accessed 6 June 2023.

The Treasury (2020) Fact sheet: JobKeeper Payment: Supporting businesses to retain jobs (treasury.gov.au)Fact sheet: Economic Response to the Coronavirus - JobKeeper Payment, The Treasury, Australian Government, accessed 6 June 2023.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2016) Health in the post-2015 development agenda: need for a social determinants of health approach, WHO, accessed 5 August 2021.

Amendments

5 February 2024 – The following errors in text were corrected:

- Under the heading ‘Overview of First Nations people’s employment status’, text was changed from:

‘a higher proportion of males than females were unemployed (8.3% compared with 6.6%)’

To:

‘a higher proportion of males than females were unemployed (8.3% compared with 6.5%)’. - Under the heading ‘Employment’, under the subheading ‘Employment by education level and sex’, text was changed from:

‘The full-time employment rate (the proportion of people of workforce age who are employed full time) for First Nations people was 30% in 2021.’

To:

‘The full-time employment rate (the proportion of people of workforce age who are employed full time) for First Nations people was 29% in 2021.’ - Under the heading ‘Employment’, under the subheading ‘Employment by education level and sex’, text was changed from:

‘The overall part-time employment rate was 18% in 2021 for First Nations people; however, a slightly different pattern emerged when viewed by education level.’

To:

‘The overall part-time employment rate was 17% in 2021 for First Nations people; however, a slightly different pattern emerged when viewed by education level.’ - Under the heading ‘Unemployment’, text was changed from:

In 2021, 7.4% of First Nations people aged 15–64 were unemployed. This has decreased from a high of 9.8% in 2016. Unemployment varies between males and females. In 2021, more males were unemployed than females (8.3% and 6.6% respectively).

To:

In 2021, 7.4% of First Nations people aged 15–64 were unemployed. This has decreased from a high of 10.5% in 2016. Unemployment varies between males and females. In 2021, more males were unemployed than females (8.3% and 6.5% respectively).