Juvenile arthritis

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Juvenile arthritis , AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Juvenile arthritis . Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/juvenile-arthritis

MLA

Juvenile arthritis . Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 14 December 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/juvenile-arthritis

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Juvenile arthritis [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/juvenile-arthritis

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Juvenile arthritis , viewed 27 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/juvenile-arthritis

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Page highlights

Juvenile arthritis is an umbrella term used to describe inflammatory arthritis in children that begins before their 16th birthday and lasts at least 6 weeks.

How many people aged 0–24 in Australia are living with arthritis?

Based on the 2021 Census and 2017–18 National Health Survey, an estimated 18,500–30,100 Australians aged 0–24 are living with arthritis.

What is the impact of juvenile arthritis?

People living with juvenile arthritis are often restricted in performing daily activities, which can put them at risk of developing further mental and physical health conditions, social isolation and educational disengagement.

- In 2020–21, there were 2,600 juvenile arthritis hospitalisations (any diagnosis) for people aged 0–24.

- People were hospitalised multiple times; in 2018–19, 890 individuals aged 0–24 had 2,400 juvenile arthritis hospitalisations.

- In 2020–21, there were 5,100 procedures performed for people aged 0–24 hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis. This equates to around 2.0 procedures per hospitalisation.

Paediatric rheumatology workforce

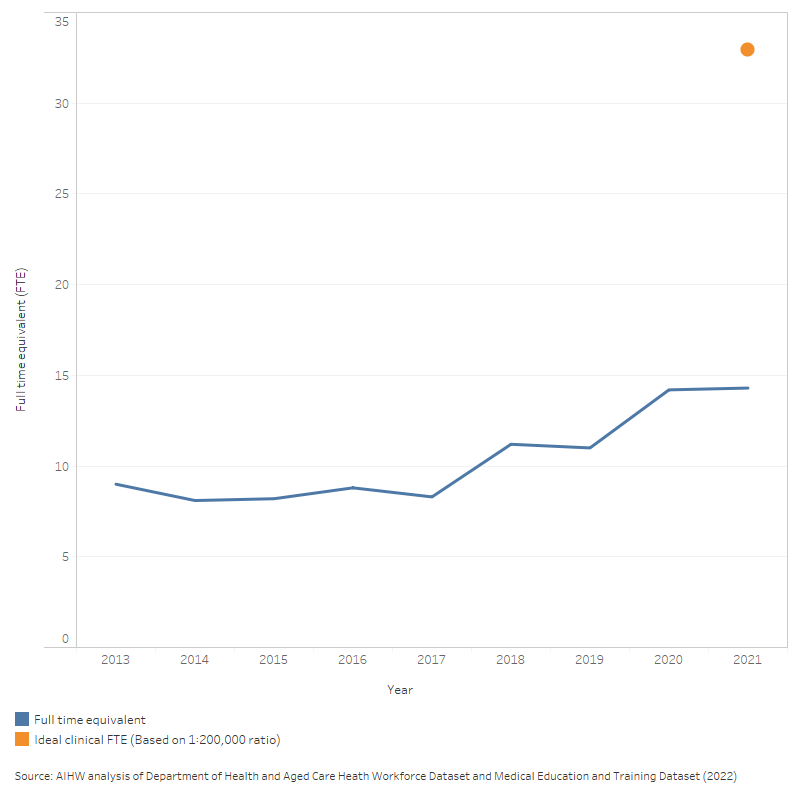

There were 17 paediatric rheumatologists (14 full-time equivalent (FTE)) in 2021, an increase over time from around 9 FTE in 2013.

Economic impact and attributable burden

- In 2023, there were an estimated 34,200 disability adjusted life years (DALYs) for people aged 0–24 with a musculoskeletal condition.

- In 2020–21, an estimated $696.5 million of expenditure in the Australian health system was attributed to musculoskeletal conditions for people aged 0–24.

What is juvenile arthritis?

Juvenile arthritis is an umbrella term used to describe inflammatory arthritis in children that begins before their 16th birthday and lasts at least 6 weeks. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common form of arthritis in children, and the terms 'juvenile idiopathic arthritis' and 'juvenile arthritis' are used interchangeably in this report. The signs and symptoms of juvenile arthritis typically vary from child to child. Juvenile arthritis is an autoimmune disease, meaning it is caused by a confused immune system attacking the joints, eyes, skin, organs and other parts of the body. Children living with arthritis may experience recurrent joint and muscle pain, skin diseases, high fevers and vision problems, including blindness. Although arthritis is often the main or first symptom, it is a multisystem disorder that can affect many parts of the body (Zaripova et al. 2021).

While the cause of the condition is often unknown (‘idiopathic’ means the cause is not known), studies have noted genetic and environmental factors such as infectious exposures may trigger disease onset (Horton and Shenoi 2019).

Although juvenile arthritis is typically defined as arthritis in those aged 0–15, many children and adolescents will continue to have active disease into adulthood. These patients may have their diagnosis re-classified into other forms of adult arthritis (Oliveira-Ramos et al. 2016), but are assumed to continue to broadly reflect a juvenile arthritis cohort. As a result, national prevalence and hospital statistics presented throughout the report will include data for people aged 0–24.

What are the sub-types of juvenile arthritis?

There are several sub-types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, which are categorised by distinct clinical features, disease diagnosis and treatment techniques.

The sub-types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis include:

- oligoarthritis (4 or less joints involved)

- polyarthritis (5 or more joints involved)

- seronegative polyarthritis

- seropositive polyarthritis

- enthesitis-related arthritis

- systemic-onset arthritis

- psoriatic arthritis

- undifferentiated arthritis (see Box 1; Barut et al. 2017).

Box 1: International League of Associations for Rheumatology classifications for juvenile idiopathic arthritis

First proposed in 1995, and later revised in 1997 and 2001, the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) is a globally recognised classification system commonly used by rheumatologists and medical practitioners to diagnose arthritis in children. The classification system uses a combination of diagnostic criteria and observed clinical features to assign 1 of 7 juvenile arthritis sub-types below.

- Oligoarthritis (or oligoarticular arthritis) typically occurs in children aged 0–4 and more commonly affects females. Oligoarthritis frequently affects the large joints (for example, knees, ankles and wrists) for many children, and is characterised by the presence of anti-nuclear antibodies. Oligoarthritis is divided into either persistent or extended, based on the number of joints affected:

- Persistent oligoarthritis affects 1–4 joints.

- Extended oligoarthritis is diagnosed if the total number of affected joints is ≥5 after the first 6-months.

- Seronegative polyarthritis (or seronegative polyarticular arthritis) is diagnosed if 5 or more joints are affected within the first 6 months of disease, and rheumatoid factor (RF) is not present in pathology. Children with polyarthritis are much more likely to be RF-negative than adults with polyarthritis.

- Seropositive polyarthritis (or seropositive polyarticular arthritis) is diagnosed if 5 or more joints are affected within the first 6 months of disease and 2 or more rheumatoid factor pathology tests (taken at least 3 months apart) are positive. This subtype is rare in children but is analogous to rheumatoid arthritis which occurs in adults.

- Enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) predominantly affects the joints in the spine and lower legs of children. According to the ILAR, children with 2 or more of the following symptoms would meet the clinical criteria:

- presence or history of sacroiliac joint tenderness (the joint between the spine and pelvis) with or without inflammatory pain in the lower back and spine (lumbosacral region)

- presence of HLA B27 antigen

- onset of arthritis in a male over 6 years of age

- acute (symptomatic) anterior uveitis

- history of ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis-related arthritis, sacroiliitis with inflammatory bowel disease, reactive arthritis, or acute anterior uveitis in a first-degree relative.

- Systemic-onset arthritis is diagnosed if there is arthritis in 1 or more joints with, or preceded by, fever of at least 2 weeks duration. Signs or symptoms must have been documented daily for at least 3 days and accompanied by 1 or more of the following:

- recurrent rash

- swelling of lymph nodes

- swelling in the liver and spleen

- inflammation of other tissues and organs in the body.

- Psoriatic arthritis is diagnosed if there is arthritis and psoriasis, or arthritis and at least 2 of the following:

- dactylitis (inflammation of fingers, toes and/or joints)

- nail pitting (dents in fingernail or toenails)

- onycholysis (separation of nail from nail bed)

- family history of psoriasis (in a first-degree relative).

- Undifferentiated arthritis is diagnosed if there is arthritis that does not fulfil criteria in any of the above categories or that fulfils criteria for 2 or more of the above categories (Petty et al. 2004; Li et al. 2022).

How is juvenile arthritis diagnosed?

The diagnosis of juvenile arthritis is predominantly based on medical history, symptoms and physical examination. Juvenile arthritis is extremely diverse in its clinical characteristics and can mimic other inflammatory conditions including leukaemia and other cancers, infections, as well as congenital and structural abnormalities (Furness et al. 2022; Demir et al. 2019). Consequently, the time from disease onset to diagnosis may be delayed.

There are no specific tests that conclusively diagnose juvenile arthritis. Blood tests including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibody (ANA), C-reactive protein (CRP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) are useful for making the diagnosis but do not always reflect active disease and may be negative, even in a child with significant arthritis. A combination of blood tests and imaging services (X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound) are recommended to exclude other forms of arthritis and predict patients at risk of developing severe disease (Boros and Whitehead 2010).

How many people aged 0–24 in Australia are living with arthritis?

Based on the 2021 Census and 2017–18 National Health Survey, between 18,500 to 30,100 Australians aged 0–24 are living with arthritis.

In Australia, there are no national data sources that specifically ask respondents if they have juvenile arthritis. As a result, in this report, information about people living with arthritis is assumed to represent juvenile arthritis among children and young adults aged 0–24.

This section examines the estimated number of Australians aged 0–24 with arthritis using data from both the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021 Census and 2017–18 National Health Survey (NHS). Both of these data sources collect information about whether people had arthritis, and include children and young adults (aged 0–24, see Box 2 for more information about these data sources).

Box 2: How does the 2021 Census differ to the 2017–18 National Health Survey?

Two sources of arthritis prevalence data are used in this report, each providing a different estimate of the number of cases of arthritis among people aged 0–24 in Australia.

- Australian Census: The Census is collected from the entire population in Australia. The 2021 Census included a single, long-term health conditions question which asked people of all ages if they have been told by a doctor or nurse that they have any of ten selected health conditions, including arthritis (ABS 2021, 2022a, 2022c).

- National Health Survey: The NHS is a large, nationally representative sample survey administered by trained interviewers and asks detailed questions to help clarify whether a condition is current or long-term. The prevalence of arthritis is reported based on whether the condition was both current and had lasted, or was expected to last, for 6 months or more. The NHS relies on participants self-reporting arthritis, or in some cases another member of the household (including a parent/guardian) reporting arthritis on behalf of an individual (ABS 2019). Data from the 2020–21 NHS data is considered a break in time series from previous NHS collections and cannot be used for comparisons over time (ABS 2022b). For this reason the 2017–18 NHS was selected for the current analysis and the results represent a baseline that can be further explored in future reporting.

Self-reporting can lead to under-reporting, however, this impacts the data to a lesser extent in the NHS compared with the Census, given the conditions questions asked are more detailed and they are interviewer administered (ABS 2022a). While NHS is the recommended data source for chronic condition prevalence data for conditions such as arthritis, the NHS estimates of the number of people aged 0–24 with juvenile arthritis have a high relative standard of error and should be interpreted with caution.

Given the caution required when interpreting the prevalence of juvenile arthritis estimated using the NHS, estimates from both the NHS and Australian Census are reported. Together, these results describe an estimated range of juvenile arthritis prevalence in Australia and may differ from estimates from other sources which use different methodology.

According to the 2021 Census:

- around 18,500 people aged 0–24 had been told by a doctor or nurse that they have arthritis. Of which, around 4,000 people (22%, 86 per 100,000 population) were aged 0–14, with the remaining 14,500 (78%, 480 per 100,000 population) aged between 15–24

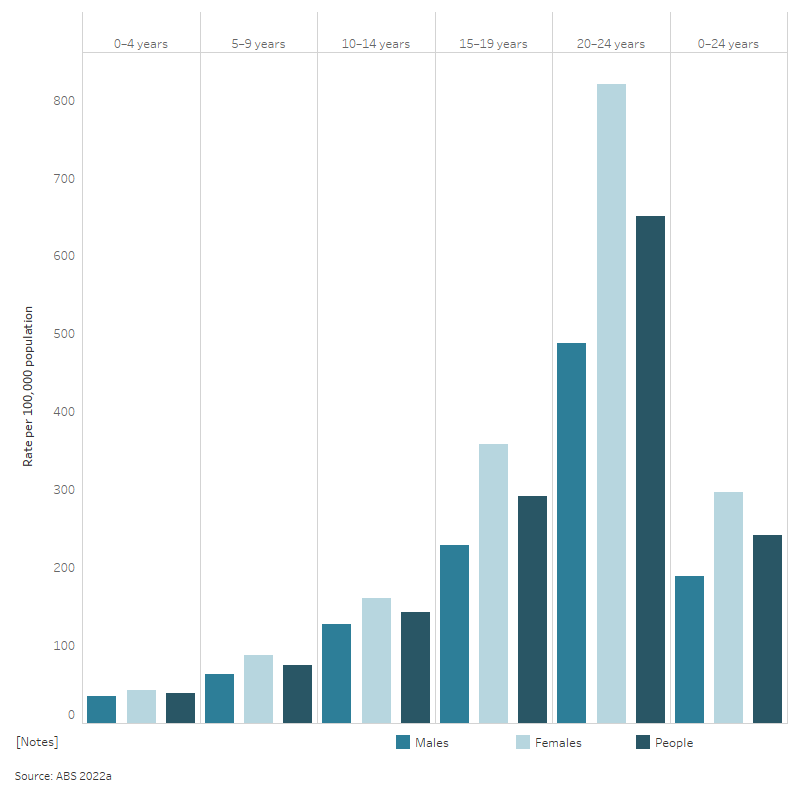

- prevalence rates increased with increasing age, from 38 per 100,000 population in the 0–4 age group to 651 per 100,000 population in the 20–24 age group. Prevalence was higher among females (57%) at all age groups than males (43%) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of arthritis based on the 2021 Census, people aged 0–24, 2021

This vertical bar chart shows the crude rate (per 100,000 population) of people aged 0–24 with arthritis based on data from the 2021 Australian Census. The prevalence of arthritis was highest amongst people aged 20–24 for both males and females (488 and 820 per 100,000 population, respectively).

An estimated 30,100 people aged 0–24 had arthritis (current and long-term) in 2017–18, using data from the 2017–18 NHS (AIHW analysis of ABS 2018a). The estimated rate of juvenile arthritis was between 241 and 383 per 100,000 population aged 0–24 using data from the 2021 Census and 2017–18 NHS, respectively. This suggests juvenile arthritis is about as common as diabetes in Australia, which was estimated to affect 25,100 children and young adults (aged 0–24) at a rate of 320 per 100,000 population in 2021, based on data from National Diabetes Services Scheme and Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group state-based registers (AIHW 2023a).

Arthritis is one of several chronic musculoskeletal conditions captured in the NHS. Overall, 379,500 people aged 0–24 had any disease of the musculoskeletal system in 2017–18 (including arthritis, back problems, osteoporosis, as well as other musculoskeletal conditions) (ABS 2018b).

Prevalence of arthritis in people aged 0–24 over time

Based on self-report data from the NHS, the estimated prevalence of people living with arthritis aged 0–24 fluctuated between 2011–12 and 2017–18. The estimated prevalence increased from 36,100 (492 per 100,000 population) in 2011–12 to 49,400 (649 per 100,000 population) in 2014–15, before decreasing to 30,100 (383 per 100,000 population) in 2017–18. However, caution is required when interpreting these data; estimates of arthritis in people aged 0–24 from the NHS have a high relative standard error, which might contribute to the fluctuation of these estimates over time. See Box 3 for more information.

Box 3: Caveats when considering juvenile arthritis prevalence and hospitalisation data

Juvenile arthritis prevalence

Estimates of the number of people with juvenile arthritis, and how well NHS data reflects the true prevalence of arthritis in people aged 0–24, may be influenced by multiple factors, including:

- the definition of juvenile arthritis used

- the method of data collection (for example self-report survey compared with registry or other data). Given the estimates are obtained from a sample survey rather than the entire population they are subject to sampling variability. Relative standard error (RSE) is a measure of sampling error and provides an immediate indication of the percentage errors likely to have occurred due to sampling. Estimates with an RSE of less than 25%, are sufficiently reliable. Relative standard errors between 25% and 50% should be used with caution. Estimates with a RSE greater than 50% are subject to high sampling error and considered too unreliable for general use

- the level of awareness of juvenile arthritis and the shortage of paediatric rheumatologists in Australia, which may delay diagnosis (see Paediatric rheumatology workforce).

Juvenile arthritis hospitalisations and health service use

For a person living with a chronic condition such as juvenile arthritis or diabetes, being admitted to hospital may be due to a range of things, including initial diagnosis, treatment for the management of the condition or complications, or an issue unrelated to the condition. Some conditions are also more likely to be recorded in a hospital record than others. Juvenile arthritis is only recorded when there is significant treatment required, investigations needed, and resources used in the hospitalisation, while conditions such as diabetes mellitus should always be coded when documented in a hospitalisation (AIHW 2023a). As such, the number of patients with juvenile arthritis may be underestimated in hospital data.

Also, hospitalisations are only one aspect of health service use. Data about other health services used, such as general practitioners (GPs) and specialists, would give a more complete picture of how many people with juvenile arthritis are using health services in Australia. However, there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection monitoring provision of care by GPs. See Treatment and management.

International prevalence

International prevalence estimates of juvenile arthritis vary in the scope, age threshold and collection methodology used. While this report primarily presents data for young people aged 0–24, this section of the report also provides estimates of the prevalence of arthritis among younger children using currently available data in Australia to better compare to international prevalence estimates.

Estimates of arthritis in children aged 0–14 using the 2017–18 NHS must be interpreted with caution and are estimated at around 100 per 100,000 population (ABS 2018b). In the 2021 Census, the rate of arthritis among children aged 0–14 is estimated at 86 per 100,000. These results are generally consistent with other Australian studies which have estimated that juvenile arthritis affects 100–400 per 100,000 children aged 0–15 (Manners and Bower 2002). Estimates presented here may differ from those reported elsewhere due to differences in the data source, including differences in the method of data collection, age threshold and definition of juvenile arthritis.

Broadly consistent with rates in Australia, juvenile arthritis prevalence rates are estimated to range between 85–102 per 100,000 population among children aged 0–15 in the United Kingdom (2000–18) and Canada (2016–17), to 150 per 100,000 population in Germany (ages 2–15) (Miranda et al. 2019; Horneff et al. 2022; Costello et al. 2022; Public Health Agency of Canada 2020). There are an estimated 3 million children living with juvenile arthritis globally, with prevalence rates highest amongst girls (Al-Mayouf et al. 2021). Juvenile arthritis varies by ethnicity, gender, socio-economic background and climate. Socio-economic disparities, access to health services, workforce variation and awareness of rheumatic diseases may impact the data on the number of diagnosed juvenile arthritis cases reported in different countries (Al-Mayouf et al. 2021).

What is the impact of juvenile arthritis?

Juvenile arthritis often has significant variation in its presentation, prognosis and complications. Typically, juvenile arthritis has an unpredictable pattern of disease where periods without symptoms are followed by a sudden reappearance of signs and symptoms known as ‘flares’. Health and wellbeing outcomes vary from child to child, and remission has been estimated to range from 7% at 18 months to around 40% after at least 10 years (Boros and Whitehead 2010; Shoop-Worrall et al. 2017). An estimated 30–56% of children with juvenile arthritis will experience severe functional limitation (Packham and Hall 2002).

People living with juvenile arthritis are often restricted in performing daily activities, which can put them at risk of developing further mental and physical health conditions, social isolation and educational disengagement. If not properly treated, people may experience growth and developmental delays, educational disruption, life-long joint damage, reduced bone density, postural abnormalities, muscle atrophy, higher psychological distress and even permanent disability (Barut et al. 2017; Ben–Ezra et al. 2007; Maresova 2011).

Managing chronic conditions can often be complex, expensive and take a psychological, social and economic toll on the children affected by juvenile arthritis and their families (Jeon et al. 2009). Emotional and mental health disorders, including mood-affective disorders, anxiety and phobias, can co-exist in these children (Fair et al. 2019; Bouaddi et al. 2017; Laila et al. 2016). Needle and procedural phobia is also common and can be debilitating (Mulligan et al. 2013). The impact on family members is also profound, including high rates of anxiety and depression symptoms and missed work time (Fair et al. 2019; Rasu 2015).

An inquiry into childhood rheumatic diseases and juvenile arthritis was announced by the former House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport in December 2021 (the Committee). The Committee identified 4 key areas in need of immediate attention in their interim report:

- the shortage of staff across the rheumatology workforce

- the need for better education and awareness of childhood rheumatic diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- improved access to medication and treatments

- the need for a well-established transition service or process for paediatric patients moving into adult care (Parliament of Australia 2022).

A full list of the 15 recommendations can be found at the Inquiry into childhood rheumatic diseases: Interim report.

Australian stories about living with juvenile arthritis

Patient stories about living with juvenile arthritis are published by the Juvenile Arthritis Foundation Australia, see Our kids. Personal accounts are not necessarily representative of the circumstances of other people with juvenile arthritis or the challenges they may face, but may give readers a greater awareness and understanding of the diversity of people’s experiences with juvenile arthritis.

Treatment and management

This section:

- provides an overview on the treatment and management of juvenile arthritis in Australia

- reports on the volume of hospital activity attributed to juvenile arthritis, including the number of hospitalisations (principal and/or additional diagnosis), procedures administered, length of stay and comorbid conditions for children and young adults aged 0–24.

Primary care

Primary health care covers health care that is not related to a hospital visit, including health promotion, prevention, early intervention, treatment of acute conditions and management of chronic conditions, and is provided by general practitioners, allied health professionals or specialists (Department of Health and Aged Care 2015).

The treatment of juvenile arthritis is often complex and requires ongoing care from a multidisciplinary team including:

- paediatric rheumatologists

- paediatric clinical nurse specialists

- ophthalmologists

- general practitioners (GPs)

- paediatric physiotherapists

- psychologists

- occupational therapists

- podiatrists (Davies et al. 2010).

There is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection monitoring provision of primary care . For more information on staff across the rheumatology workforce, see Paediatric rheumatology workforce.

Medications

Pharmaceutical treatment for juvenile arthritis aims to control pain and the inflammatory process and prevent long-term joint damage without potential medication side effects. The broad classes of medications available for treating juvenile arthritis include:

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

- biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs)

- corticosteroids (see Box 4).

Studies have found that a higher number of medications tends to be associated with a greater disease activity and level of pain (Montag et al. 2022). Levels of medication usage have also been associated with different clinical factors, such as type of juvenile arthritis, and demographic factors, such as sex. Over a one-year period, 94% of patients newly diagnosed with juvenile arthritis between 2010 and 2014 at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne received NSAIDs, 62% intra-articular steroids, 62% methotrexate (a type of DMARD), 53% oral corticosteroids, and 15% a biologic DMARD. At 12 months 65% had no active joint disease, though more than half remained on medication (Tiller et al. 2018).

A commonly used DMARD in the treatment of juvenile arthritis, methotrexate, can cause significant gastrointestinal side effects including nausea and vomiting. Methotrexate-induced nausea may lead patients to stop taking the drug or switching to another drug. Methotrexate-induced nausea can be managed in multiple ways, including with anti-emetic (anti-nausea) medications (Falvey et al. 2017).

Box 4: Medications available for treating arthritis

NSAIDs are commonly administered anti-inflammatory agents which relieve the symptoms of inflammation and/or pain by reducing the production of prostaglandins, chemicals released by damaged cells that cause inflammation and sensitise nerve endings. Typically, NSAIDs are used to manage short-term pain, stiffness and swelling in the joints, and may be bought over the counter or with a prescription (ARA 2017).

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are specialised immunosuppressant medications that alter disease progression (Arthritis Foundation 2023). DMARDs act by decreasing the activity of the immune system (ARA 2019). Over-activity in the immune system in patients with arthritis drives inflammation in the joints and associated pain, swelling and long-term damage.

bDMARDs are a specific type of DMARD manufactured from living organisms. They work by targeted blocking of immune pathways and cytokines, which are signalling molecules that regulate inflammatory responses. bDMARDs are used to slow down rheumatic disease progression by reducing inflammation and damage to the joints (ARA 2019).

Corticosteroids, often known as steroids, are anti-inflammatory drugs commonly used to treat a variety of conditions, including rheumatic diseases. Corticosteroids are fast-acting injections or medications, which work by targeting an individual’s immune system and reducing inflammation. They are effective but can have significant short- and long-term side effects (Buchman 2001).

Based on previous analysis of de-identified unit record PBS data, it is estimated that 5,400 children (aged 0–16) were dispensed NSAIDs or DMARDs in 2016–17. For an in-depth discussion of the medications available for treating arthritis and dispensing patterns of these drugs in children, refer to Medication use for ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and juvenile arthritis 2016–17 (AIHW 2019a).

Hospital care

This section explores hospital activity attributed to juvenile arthritis in Australia using data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). The NHMD is a collection of electronic confidentialised summary records for hospitalisations (also known as separations or episodes of care) in public and private hospitals in Australia. A record is included for each hospitalisation, not for each patient, so patients who separated more than once have more than 1 record in the NHMD.

Records in the NHMD are assigned a principal diagnosis and can also be assigned one or more additional diagnoses (see Box 5).

Box 5: Key terms from the National Hospital Morbidity Database

- Additional diagnosis

- A condition or complaint either coexisting with the principal diagnosis or arising during the episode of admitted patient care, which is significant in terms of treatment required, investigations needed, and resources used in each episode of care. Multiple diagnoses may be recorded.

- Principal diagnosis

- The diagnosis established after study to be chiefly responsible for occasioning an episode of admitted patient care.

- Supplementary code

- A supplementary code is assigned for selected clinically significant chronic conditions that are part of the current health status on admission but do not meet criteria for inclusion as a principal or additional diagnosis on the patient’s hospital record.

For further information on how juvenile arthritis is defined in the NHMD refer to the Data tables.

Diagnosis data are reported to the NHMD using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM), which do not correspond to ILAR classifications. As a result, juvenile arthritis sub-typing is not included within this report.

This report uses both the principal and additional diagnosis of hospital records to explore relevant hospital activity (Box 6).

Box 6: Key terms used in this report for hospital care related to juvenile arthritis

The following terms will be used throughout this section of the report to differentiate types of hospitalisations:

- Juvenile arthritis hospitalisations are hospital records with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis. This captures all hospital activity related to juvenile arthritis.

- Hospitalisations due to juvenile arthritis represent hospital records with a principal diagnosis of juvenile arthritis. This captures hospital activity where juvenile arthritis was the main reason for the hospitalisation.

Additional diagnoses will be reported on in 2 different ways throughout the report:

- Hospitalisations with juvenile arthritis refers to records that have an additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis. This captures the hospitalisations where juvenile arthritis co-occurs with another condition or impacts care during the hospitalisation.

- Additional diagnoses associated with juvenile arthritis refers to the additional diagnoses in patients hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis. This captures conditions that co-occur and/or impact care among patients hospitalised for juvenile arthritis.

What is the total number of juvenile arthritis hospitalisations (principal and/or additional diagnosis)?

In 2020–21, there were 2,600 hospitalisations for people aged 0–24 years where juvenile arthritis was recorded as the principal and/or additional diagnosis.

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, hospitalisation rates for people aged 0–24 with a principal and/or additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis:

- were 2.1 times as high among females compared with males (45 and 21 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- were highest among people aged 10–14 years for both females and males (54 and 28 per 100,000 population, respectively).

The total number of juvenile arthritis hospitalisations are increasing over time

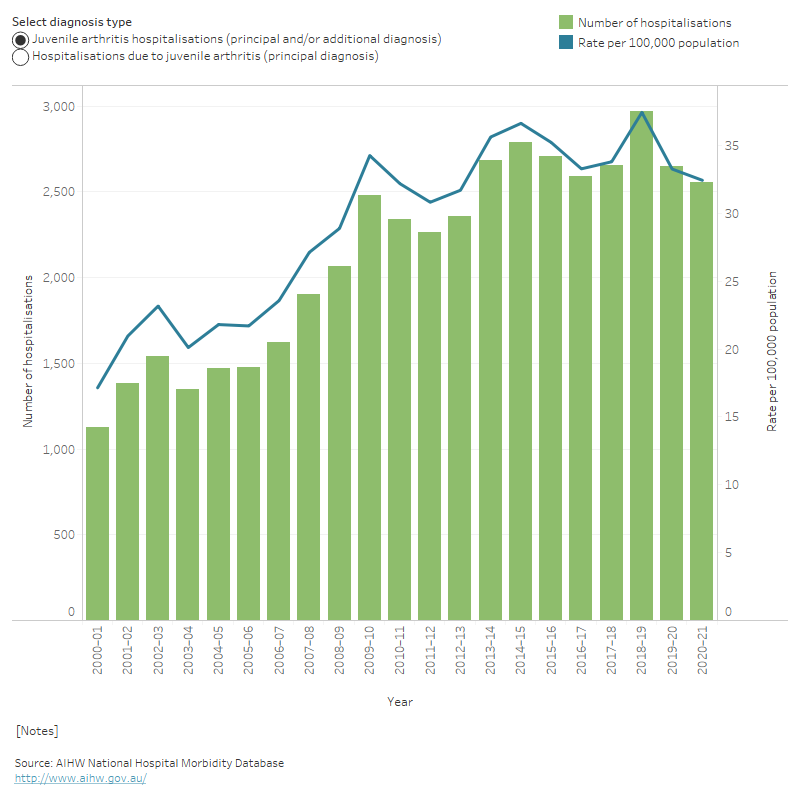

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, there were 45,000 juvenile arthritis hospitalisations (representing 0.2% of all hospitalisations for people aged 0–24 years). Of these:

- 8 in 10 (82%, or 36,800 hospitalisations) had juvenile arthritis recorded as the principal diagnosis

- two-thirds (63%, or 28,100 hospitalisations) were for females (see Figure 2).

Overall, juvenile arthritis hospitalisations have increased in the last 20 years, from 17 per 100,000 population in 2000–01 to 32 per 100,000 population in 2020–21. However, the rate of juvenile arthritis hospitalisations was 11% lower in 2019–20 and 13% lower in 2020–21, compared with the peak in 2018–19 (37 per 100,000 population). This may be associated with aspects of the early COVID-19 period and Australia’s response to it, which had an impact on the provision of healthcare services and hospital activity generally (see Box 7; AIHW 2022b). Continued monitoring as new data becomes available is required to assess the evolving impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on juvenile arthritis hospitalisations in Australia.

Box 7: Impact of COVID-19 on hospital care

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on hospital activity generally. Since February 2020, a range of social, economic, business and travel restrictions have been in place to prevent and reduce the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) and maintain adequate capacity of the healthcare system to deal with the pandemic. These initiatives have varied in terms of their geographic reach (that is, whether they applied nationally, by state/territory or on a more local level) and have varied over time.

Over this period, a number of initiatives impacted on the provision of healthcare services and reduced the flow of patients seeking in-hospital care, including:

- patients being re-directed to other healthcare services if they had symptoms consistent with COVID-19 or had been a close contact of someone who had been infected

- establishment of new modes of delivering healthcare services (for example, telehealth services and 'virtual' care models) that could re-direct patients seeking non-urgent care

- changes in patient behaviours, including changes in healthcare seeking behaviours

- restricted activities that might reduce risks for some kinds of healthcare issues, such as injuries that could result in an emergency admission to hospital.

Figure 2: Total number and rate of juvenile arthritis hospitalisations (principal and/or additional diagnosis) between 2000–01 and 2020–21, among people aged 0–24

The dual axis chart shows the number and rate per 100,000 population of hospitalisations for juvenile arthritis, by diagnosis type, from 2000–01 to 2020–21. The vertical bar chart shows the number of hospitalisations for juvenile arthritis, and the line chart shows the crude rate of hospitalisation. Over the period, hospitalisations with any diagnosis (principal and/or additional diagnosis) of juvenile arthritis increased from 1,124 hospitalisations in 2000–01 to 2,555 hospitalisations in 2020–21 (17 and 32 per 100,000 population, respectively).

For more information on how rates are calculated see Technical notes.

How many hospitalisations are due to juvenile arthritis (principal diagnosis)?

In 2020–21 there were 39,700 hospitalisations for people aged 0–24 due to musculoskeletal conditions.

Juvenile arthritis accounted for 5.6% of these, with a total of 2,200 hospitalisations.

In 2020–21, hospitalisation rates due to juvenile arthritis for people aged 0–24 were:

- 2.2 times as high among females compared to males (39 and 18 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- highest among females aged 10–14 years (49 per 100,000 population) and males aged 5–9 years (25 per 100,000 population).

Trends over time

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21, for people aged 0–24 years:

- the rate of hospitalisations due to juvenile arthritis (principal diagnosis) was 2.5 times as high in 2020–21 compared with 2000–01 (28 and 11 per 100,000 population, respectively); increasing from around 740 hospitalisations in 2000–01 to around 2,200 in 2020–21

- the rate of hospitalisation generally increased with increasing year, peaking in 2018–19 at 33 per 100,000 population (see Figure 2)

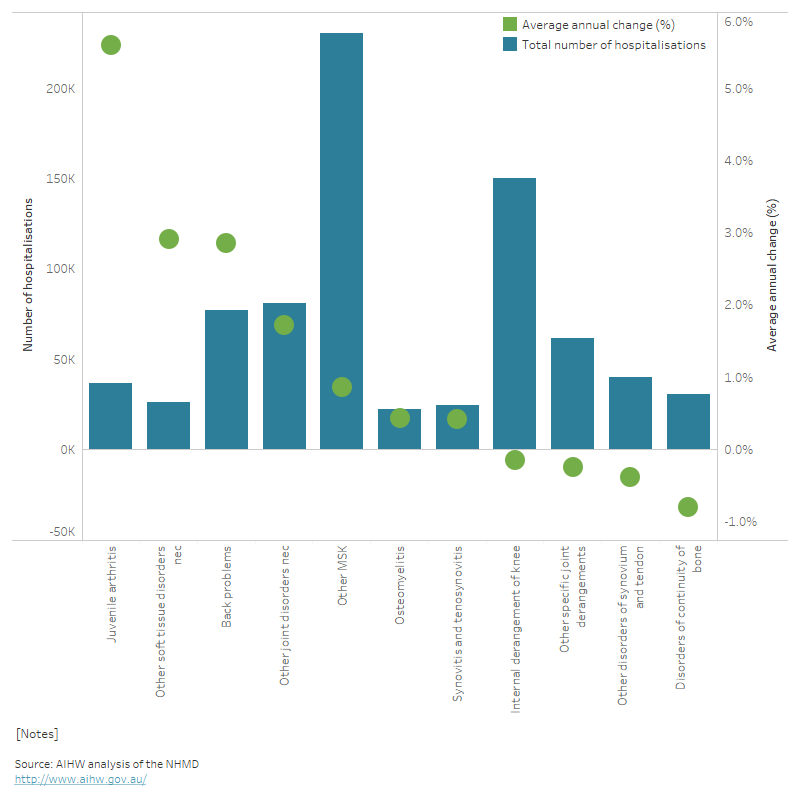

- the number of hospitalisations due to juvenile arthritis increased by 5.6% per year on average, which is almost double the average increase for other musculoskeletal and connective tissue hospitalisations (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number and average annual change (%) of hospitalisations due to musculoskeletal conditions (principal diagnosis) between 2000–01 and 2020–21, among people aged 0–24

The dual axis chart shows the total number of musculoskeletal hospitalisations and average annual percentage change (%), by condition, between 2000–01 and 2020–21. Hospitalisations due to ‘other musculoskeletal conditions’ were the most common over the period, contributing 29% (230,600) of all musculoskeletal hospitalisations, while juvenile arthritis hospitalisations had the highest annual growth (5.6%).

What additional diagnoses are associated with hospitalisations due to juvenile arthritis?

Additional diagnoses include comorbidities (co-existing conditions) and/or complications which may contribute to longer lengths of stay, more intensive treatment, or the use of greater resources.

In 2020–21, there were 1,460 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of juvenile arthritis that also had at least 1 additional diagnosis recorded, among people aged 0–24. Of these:

- almost 1 in 2 (45% or 660 hospitalisations) had an additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis

- 48 hospitalisations (3.3%) had an additional diagnosis of iridocyclitis (includes uveitis) (see Box 8).

Hospitalisations will commonly include juvenile arthritis diagnoses as both the principal and additional diagnosis. Children living with juvenile arthritis often experience pain or inflammation in more than 1 joint, and multiple diagnoses codes for juvenile arthritis may represent multiple forms of arthritis and/or the condition affecting multiple joints (see also How many hospitalisations were for patients with juvenile arthritis (additional diagnosis)?).

Box 8: Uveitis and inflammatory eye disease

Uveitis and other inflammatory eye disorders commonly occur throughout the course of juvenile arthritis, and affect around 30% of children with the disease (Clarke et al. 2016). Several studies have found that uveitis is the most common eye condition for people with juvenile arthritis, occurring in around 16 to 19% of children. Uveitis might not require active management in the hospital setting and therefore might not meet the coding standards for a recorded diagnosis. As such, an additional diagnosis of iridocyclitis among hospitalisations due to juvenile arthritis may underestimate the true prevalence of this comorbidity among people with juvenile arthritis, but reflects instances where this condition impacted care in hospital.

Uveitis can be sight threatening and cause blindness, both through the disease itself and complications from its treatment. Uveitis is typically asymptomatic, and only rarely presents symptoms. Hence annual screening, usually by an ophthalmologist, is required for all children with juvenile arthritis to reduce the risk of long-term vision impairment (Min et al. 2020; Simon et al. 2020). There is considerable overlap in the treatments for juvenile arthritis and juvenile arthritis-related uveitis (Semeraro et al. 2014).

How long are people spending in hospital due to juvenile arthritis?

Hospitalisations can vary in length, from being admitted and separated on the same day, or continuing for much longer. This section explores the number of bed days among hospital episodes where juvenile arthritis was the principal diagnosis. Bed days refer to the total number of days spent in hospital by patients, or days of patient care (AIHW 2019b).

In 2020–21:

- 1,900 (88%) hospitalisations due to juvenile arthritis were same-day separations

- patients hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis spent on average 1.3 days in hospital, accounting for 2,900 bed days

- the average length of stay was highest among males aged 20–24 years and females aged 0–4 years (1.6 and 1.5 days, respectively).

Trends over time

The average length of time that people spend in hospital due to juvenile arthritis has decreased over the past 2 decades.

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21:

- the average length of stay decreased from 2.6 days in 2000–01 to 1.3 days in 2020–21

- the average length of overnight stays decreased by 17%, from approximately 4.3 days in 2000–01 to 3.6 days in 2020–21

- the proportion of overnight hospitalisations decreased, from 48% in 2000–01 to 12% in 2020–21.

How do juvenile arthritis hospitalisations compare with diabetes hospitalisations?

While evidence suggests that the prevalence of diabetes and juvenile arthritis is comparable, health service use, such as hospitalisations, differs between the conditions. In 2020–21, there were 6,300 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of diabetes, compared with 2,200 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of juvenile arthritis, based on data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). Overall, there were 20,700 diabetes hospitalisations (principal and/or additional diagnosis) in 2020–21 and 2,600 juvenile arthritis hospitalisations (principal and/or additional diagnosis).

For a person living with juvenile arthritis or diabetes, being admitted to hospital may be due to a range of things, including initial diagnosis, treatment for the management of the condition or complications, or an issue unrelated to the condition. Additionally, diabetes mellitus should always be coded when documented in a hospitalisation, while juvenile arthritis is only recorded when there is significant treatment required, investigations needed, and resources used in the hospitalisation (AIHW 2023a).

How many procedures were performed for people hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis?

This section explores procedures performed in hospital. Information on procedures in the NHMD is reported using the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI) which classifies surgical operations, procedures and other types of interventions performed for the purpose of investigating and/or remedying health state.

In 2020–21, there were approximately 5,100 procedures performed for people aged 0–24 years hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis. This equates to around 2.0 procedures per hospitalisation.

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, rates of hospital procedures were:

- 2.2 times as high in females compared to males (90 and 42 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- highest among people aged 10–14 years (96 per 100,000 population).

What procedures are commonly performed for people hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis?

Whilst there are no procedures specific to juvenile arthritis, Cleary et al. (2013) noted that joint injections, including intra-articular corticosteroid injections, are commonly administered in hospitals, private radiology services or primary care settings. These procedures can occur during same-day hospitalisations and patients receive a combination of analgesics and anaesthesia to relieve pre- and/or post-operative pain (Oren-Ziv et al. 2015).

A large proportion of juvenile arthritis hospitalisations are associated with procedures to relieve pain and improve function. In 2020–21, the most commonly performed procedures for people hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis were classified as:

- administration of agent into other musculoskeletal sites (ACHI Block 1552, 1,800 procedures)

- cerebral anaesthesia (ACHI Block 1910, 1,000 procedures)

- administration of pharmacotherapy (ACHI Block 1920, 900 procedures) (Table 1).

| ACHI procedure block | Block description | Number of procedures performed |

|---|---|---|

1552 | Administration of agent into other musculoskeletal sites | 1772 |

1910 | Cerebral anaesthesia | 1034 |

1920 | Administration of pharmacotherapy | 903 |

1905 | Therapeutic interventions on musculoskeletal system | 406 |

1916 | Generalised allied health interventions | 308 |

Notes:

- Juvenile arthritis was classified according to ICD-10-AM, 11th edition codes 'M05', 'M06','M073', 'M08', 'M09','M13', 'M45'.

- Hospitalisations for which the care type was reported as Newborn (without qualified days), and records for Hospital boarders and Posthumous organ procurement have been excluded.

- Each procedure is counted, and individuals can have multiple procedures in a single hospitalisation and/or multiple procedures in the same ACHI procedure block.

Source: AIHW National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Trends over time

Between 2000–01 and 2020–21:

- there were 81,200 procedures performed for people aged 0–24 with a principal diagnosis of juvenile arthritis

- rates of procedure were 2.6 times as high in 2020–21 (65 per 100,000 population), when compared to 2000–01 (25 per 100,000 population).

How many hospitalisations were for people with juvenile arthritis (additional diagnosis)?

In 2020–21, there were 750 hospitalisations for people aged 0–24 where an additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis was recorded.

What is the main reason for hospitalisation among hospitalisations with juvenile arthritis?

In 2020–21, among the 750 hospitalisations with juvenile arthritis (additional diagnosis), most had juvenile arthritis as the principal diagnosis (53%). Of those hospitalisations that did not have juvenile arthritis as the principal diagnosis, the most common principal diagnoses were:

- psoriasis (8.9% or 31 hospitalisations)

- iridocyclitis (including uveitis) (8.9% or 31 hospitalisations)

- ulcerative colitis (4.3% or 15 hospitalisations).

Other studies have noted that respiratory conditions, mood and depressive disorders, diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, immune disease and type 1 diabetes are common comorbid conditions in people living with juvenile arthritis (Min et al. 2020; Fair et al. 2019).

Trends over time

In July 2015, a new coding standard (ASC 003 ‘Supplementary codes for chronic conditions’) was introduced to capture clinically significant chronic conditions (including arthritis) across the hospitalised population. Given the magnitude of their capture and the impact on the allocation of additional diagnoses codes, they constitute a break in time series for statistical interpretation. For this reason, additional diagnosis trends are only reported for the period of 2015–16 to 2020–2021. See Box 9 for further information on how supplementary chronic condition U codes could be used in juvenile arthritis monitoring.

Between 2015–16 and 2020–21:

- the number of hospitalisations with an additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis decreased 14%, from 870 hospitalisations in 2015–16 to 750 hospitalisations in 2020–21

- the hospitalisation rate for people aged 0–24 years with an additional diagnosis of juvenile arthritis has stayed between 10–12 per 100,000 population.

Box 9: About supplementary chronic condition U codes

In July 2015, a list of 29 supplementary codes for chronic conditions (U78–U88) were incorporated in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) 9th edition.

These codes represent a distinct list of clinically significant chronic conditions, which are part of the patient’s current health status on admission but do not meet the criteria for inclusion as a principal and/or additional diagnosis in that episode of care.

Using supplementary chronic condition codes to identify additional comorbid conditions

Conditions co-occurring with juvenile arthritis may be assigned as a supplementary U code, rather than an additional diagnosis. As a result, supplementary U codes may provide further insight into the co-occurring conditions experienced by children and young adults hospitalised with a diagnosis of juvenile arthritis.

Between 2015–16 and 2020–21, there were 810 hospitalisations with any supplementary U code assigned for people aged 0–24 hospitalised due to juvenile arthritis. The most commonly reported chronic conditions were asthma (49%), followed by depression (15%) and disorders of intellectual development (9%).

Using supplementary chronic condition codes to identify possible juvenile arthritis patients

Between 2015–16 and 2020–21, for people aged 0–24:

- there were 7,500 hospitalisations with at least 1 supplementary arthritis code recorded (U86.1, U86.2)

- the number of hospitalisations with a supplementary arthritis code recorded increased 27%, from 1,100 in 2015–16 to 1,400 in 2020–21.

While these supplementary codes are not currently included in the definition of juvenile arthritis, they may increase the capture of arthritis in the hospitalised population. Future work will assess the interpretation and use of these codes in chronic condition reporting.

Using linked data to explore how many people are hospitalised for juvenile arthritis

890 individuals aged 0–24 had 2,400 juvenile arthritis hospitalisations in linked hospital data in 2018–19

People with juvenile arthritis may have complicated care in hospital. A single individual might be hospitalised several times over the course of their disease, resulting in several episodes of care in the NHMD. While NHMD data provides a comprehensive picture of hospital use for juvenile arthritis, national linked data provides insight into the number of people hospitalised for juvenile arthritis.

There were 890 people aged 0–24 who had at least 1 juvenile arthritis hospitalisation (principal and/or additional diagnosis) in 2018–19, using national linked data (Box 10). This corresponded to around 2,400 juvenile arthritis hospitalisations (covering 79% of those captured in NHMD data). As such, people with juvenile arthritis may be admitted to hospital multiple times in a year. Of people aged 0–24 hospitalised for juvenile arthritis in 2018–19:

- 68% had one hospitalisation in that year

- 15% had 2 hospitalisations

- 17% had 3 or more hospitalisations.

Box 10: About the national linked data

The section uses data from the National Integrated Health Services Information Analysis Asset (NIHSI AA). NIHSI AA contains linked unit record level admitted patient episode data, which is drawn from the NHMD. Records are provided from all public hospitals in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, and Australian Capital Territory from July 2010 to June 2019. In addition, private hospitals data (where available) for Victoria from July 2010 to June 2017, and for Queensland and Australian Capital Territory from July 2010 to June 2019 are included.

Future work using linked data

Without linked hospital data, it is not possible to count the number of people hospitalised each year as reported in this section. This is because hospital episodes belonging to the same patient cannot be identified in the NHMD. This report begins to explore how linked hospitals data can be used to enhance reporting on the management of juvenile arthritis. Additional care may also be recorded across different databases, including Medicare Benefits Scheme and Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule data. Future work will explore the feasibility of using linked data sources to explore patient pathways and health care outcomes for people with juvenile arthritis.

Outpatient services

Outpatient services is care provided by a clinician at a hospital where the patient is not admitted into hospital. Data on outpatient services in public hospitals and Local Hospital Networks is collected with information on clinic speciality in the non-admitted patient database, unit record database (NAPUR; see Box 11). Children with juvenile arthritis may be seen by specialists in outpatient clinics, including rheumatology services. Paediatric rheumatologists specialise in the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, connective tissue diseases and inflammatory conditions for children and young people. At present, there are no paediatric specific rheumatology clinics in the Australian Capital Territory, Northern Territory and Tasmania, and children with juvenile arthritis may see adult rheumatologists.

This section reports on outpatient services at rheumatology clinics. Outpatient data do not include diagnosis information, so services cannot be specifically associated with patients diagnosed with juvenile arthritis. As such, attendance to an outpatient rheumatology service is likely to be attributed to diseases beyond juvenile arthritis, but broadly reflect services for musculoskeletal and inflammatory conditions among children and young adults. Further, no distinction can be made between paediatric and adult rheumatology services from the current data.

Box 11: Data limitations of the Non-Admitted Patient database, unit record (NAPUR) database

The non-admitted patient, unit record database, holds episode-level data on service events for non-admitted patients in public hospital outpatient clinics. As a result, private hospital outpatient data is not included in the analysis presented below. When interpreting the data presented below, the following limitations should be considered:

- There is significant variation amongst Australian states and territories and between reporting years in the way in which non-admitted patient occasions of service data are collected for the NAPUR. States and territories may differ in the extent to which outpatient services are provided in non-hospital settings (such as community health services).

- Data presented below are counts of occasions of service, not people. A person may have multiple occasions of service, at a variety of outpatient clinics or departments reported in a reference year.

- In 2020–21, 75% of data provided to the non-admitted patient care data collections was episode-level data (NAPUR).

Variation by age and sex

In 2020–21, for people aged 0–24:

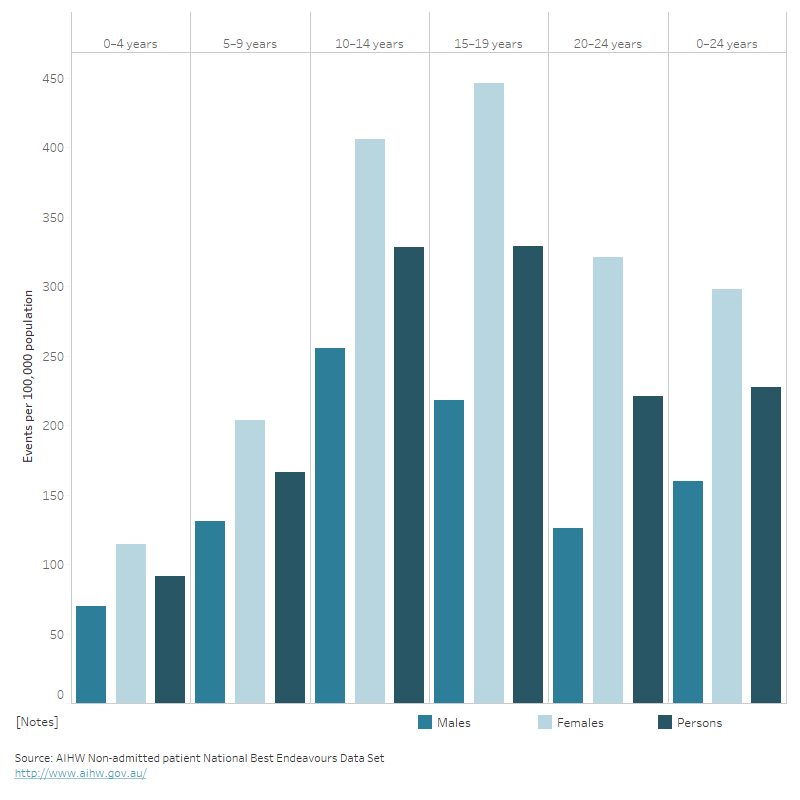

- there were 17,900 service events at public outpatient rheumatology clinics across Australia

- rate of service events at outpatient rheumatology clinics were highest amongst males aged 10–14 (256 per 100,000 population) and females aged 15–19 (446 per 100,000 population) (see Figure 4)

- rates of service events at outpatient rheumatology clinics was highest in Major cities (245 per 100,000 population) and lowest in Very remote areas (105 per 100,000 population).

Figure 4: Service events at outpatient rheumatology clinics, people aged 0–24, 2020–21

The vertical bar chart shows the rate per 100,000 population of non-admitted patient care events at outpatient rheumatology clinics, by sex, for people aged 0–24, in 2020–21. Rates of service events were highest amongst males aged 10–14 (256 per 100,000 population) and females aged 15–19 (446 per 100,000 population).

Paediatric rheumatology workforce

Paediatric rheumatologists are specialist paediatricians with expertise in the diagnosis and management of children and adolescents with diseases that affect the joints, bones and muscles (Tiller and Allen 2017). Early referral to a rheumatologist is recommended for children with diagnosed or suspected juvenile arthritis (RACGP 2009). Commonly treated conditions include juvenile arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, vasculitis and scleroderma (Agency for Clinical Innovation New South Wales 2013).

There is a critical shortage of paediatric rheumatologists across Australia, particularly in rural and remote regions, leaving children without access to local paediatric rheumatology care.

The number of clinical FTE paediatric rheumatologists required to meet ideal capacity and rheumatology care models (1 paediatric rheumatologist per 200,000 children) is 32 FTE. However, the Australian Government’s National Health Workforce Data Set (NHWDS) estimates that there were 17 paediatric rheumatologists (14 full-time equivalent (FTE)) in 2021, an increase over time from around 9 FTE in 2013 (Figure 5). Similarly, the 2021 ARA Survey estimated 20 practising paediatric rheumatologists (13 FTE) in 2021. Based on current work patterns (such as part-time work), this corresponds to a current shortfall of 41 paediatric rheumatologists (Australian Rheumatology Association 2023).

The 2021 ARA Survey found that most paediatric rheumatology services were conducted in the public setting (54%), and no paediatric rheumatologists reported practising in public and/or private rural hospitals (Australian Rheumatology Association 2023).

Figure 5: Number full-time equivalent (FTE) paediatric rheumatologists in national workforce, 2013–2021

The line chart shows the number of full-time equivalent registered paediatric rheumatologist in Australia’s workforce between 2013–2021. Over the period, the number of full-time equivalent paediatric rheumatologists increased from 9 to 14 FTE.

Economic impact and burden of disease

Juvenile arthritis is one of several inflammatory rheumatic diseases that cause musculoskeletal pain and disability. The Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS) provides burden estimates for over 200 diseases and injuries in Australia for 2023, 2018, 2015, 2011 and 2003. Burden of disease analysis is a way of measuring the impact of diseases and injuries on a population (in this report, children and young adults aged 0–24). Disease expenditure data analyses Australia’s national health spending and is presented using ABDS conditions.

Juvenile arthritis is not currently individually specified in ABDS conditions. Arthritis is captured across 3 separate conditions:

- rheumatoid arthritis

- osteoarthritis

- other musculoskeletal conditions (includes other or unknown arthritis types, as well as other diseases of the musculoskeletal system).

Other forms of arthritis, which may include juvenile arthritis, are not separated from other musculoskeletal conditions.

Overall, there were 379,500 peopled aged 0–24 who had any disease of the musculoskeletal system in the 2017–18 NHS, of which 30,100 (7.9%) reported arthritis. Further, juvenile arthritis accounted for 5.6% of the 39,700 hospitalisations for people aged 0–24 due to musculoskeletal conditions. As such, this section of the report describes the economic impact and attributable burden of all childhood musculoskeletal conditions, some of which is expected to be due to juvenile arthritis.

Burden of disease

Box 12: What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

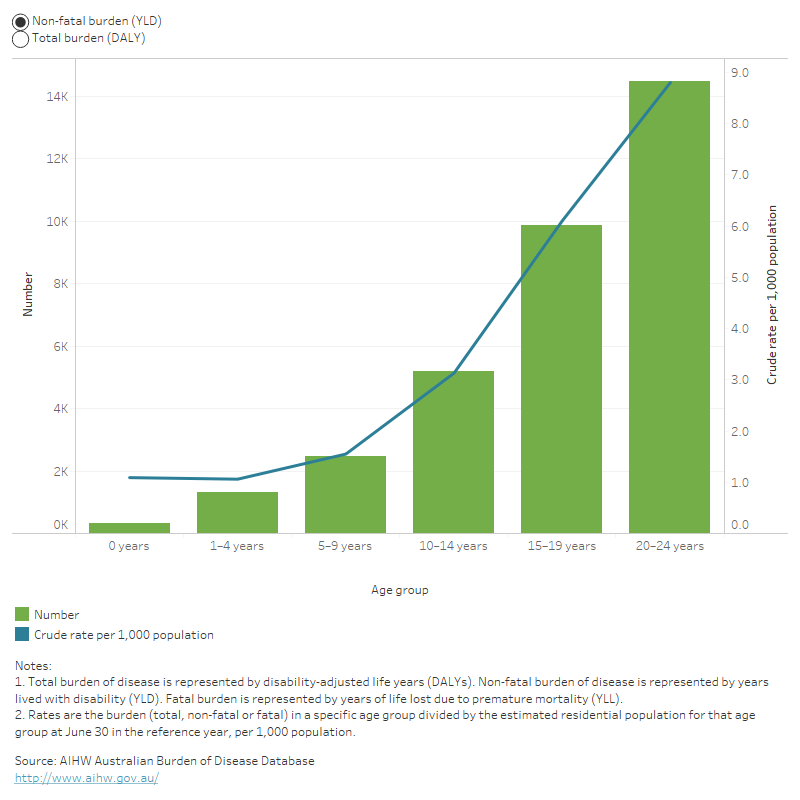

In 2023, musculoskeletal conditions accounted for 34,200 disability adjusted life years (DALY) for people aged 0–24 (AIHW 2023b). This represented 5.4% of DALY for people aged 0–24 years, and a rate of 4.2 per 1,000 population.

For people aged 0–24 years, most of the burden from musculoskeletal conditions came from years lived with disability (YLD) (98%) with the remaining (2%) attributed to years of life lost to premature death (YLL).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023:

- the rate of total burden attributed to musculoskeletal conditions was slightly higher in females aged 0–24 compared with males aged 0–24 (4.4 and 4.1 DALY per 1,000 population)

- the rate of burden of musculoskeletal conditions increased with age, accounting for 2.0 DALY per 1,000 population among people aged 0–14 and 7.5 per 1,000 population among people aged 15–24 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Total burden and non-fatal burden attributed to musculoskeletal conditions among people aged 0–24, 2023

This figure shows the burden of disease for people with musculoskeletal conditions increased from 1.2 to 8.9 DALY per 1,000 population from age 0 years to 20-24 years.

Trends over time

Between 2003 and 2023:

- the non-fatal burden attributed to musculoskeletal conditions for people aged 0–14 years was 2.3 times as high in 2023 compared to 2003 (9,300 and 4,000 YLD, respectively)

- the rate of non-fatal burden attributed to musculoskeletal conditions increased for people aged between 0–14 years (from 1.0 to 2.0 per 1,000 population) and decreased for those aged 15–24 years (from 8.3 to 7.5 per 1,000 population) (AIHW 2023b).

Disease expenditure

In 2020–21, an estimated $696.5 million of expenditure in the Australian health system was attributed to musculoskeletal conditions for people aged 0–24. This represented 3.9% of total health expenditure for the 0–24 age group (AIHW 2023c).

Who is the money spent on?

In 2020–21, musculoskeletal expenditure for people aged 0–24 was slightly higher for males ($356.5 million) compared with females ($340 million).

While conditions such as juvenile arthritis are more common in females than males, there may be other musculoskeletal conditions involving high expenditure for males that contribute to this pattern.

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–21, 74% ($515.0 million) of health system expenditure for musculoskeletal conditions in people aged 0–24 was attributed to hospital services. Of which:

- $208.0 million (40% of hospital related spending) was attributed to public admitted patient hospital services

- $167.5 million (33%) was attributed to private hospital services

- $85.9 million (17%) was attributed to public hospital outpatient services

- $53.6 million (10%) was attributed to public hospital emergency departments.

The remaining 26% ($181.5 million) of expenditure was related to non-hospital medical services, comprising general practitioner (GP) services ($50.6 million), Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme ($40.2 million), medical imaging ($43.7 million), specialist services ($17.4 million), allied health and other services ($17.1 million) and pathology ($12.6 million).

Data sources

Australian Burden of Disease Study

The Australian Burden of Disease Study undertaken by the AIHW provides information on the burden of disease for the Australian population. Burden of disease analysis measures the impact of fatal burden (or years of life lost, YLL) and non-fatal burden (years lived with disability, YLD), with the sum of non-fatal and fatal burden equating the total burden (disability-adjusted life year, DALY).

The 2023 study builds on the AIHW’s previous burden of disease studies and disease monitoring work. It provides Australian-specific estimates for over 200 diseases and injuries, grouped into 17 disease groups, for 2003, 2011, 2015 and 2018.

Detailed findings were released on 14 December 2023, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023.

Australian Census 2021

The Census of Population and Housing (the Census) is collected every 5 years and counts every person and household in Australia. The most recent Census was conducted on 10 August 2021.

For the first time, the 2021 Census asked Australians about 10 common long-term health conditions. These include arthritis, asthma, cancer (including remission), dementia (including Alzheimer’s), diabetes (excluding gestational diabetes), heart disease (including heart attack or angina), kidney disease, lung condition (including COPD or emphysema), mental health condition (including depression or anxiety), stroke and any other long-term health condition(s). See Census for more information.

Australian Disease Expenditure Database

The AIHW Disease Expenditure Database provides a broad picture of the use of health system resources classified by disease groups and conditions.

It contains estimates of expenditure by the Australian Burden of Disease Study diseases and injuries, age group, and sex for admitted patient, emergency department and outpatient hospital services, out-of-hospital medical services, and prescription pharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutical benefit scheme expenditure includes over and under co-payment prescriptions.

It does not allocate all expenditure on health goods and services by disease – for example, neither administration expenditure nor capital expenditure can be meaningfully attributed to any particular condition due to their nature.

For more information, see Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21.

Australian National Hospital Morbidity Database

The National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) is compiled from data supplied by the state and territory health authorities. It is a collection of electronic confidentialised summary records for hospitalisations (also known as separations or episodes of care) in public and private hospitals in Australia.

The NHMD is based on the Admitted Patient Care National Minimum Data Set (APC NMDS). It records information on admitted patient care in hospitals in Australia, and includes demographic, administrative and length-of-stay data, as well as data on the diagnoses of patients, the procedures they underwent in hospital and external causes of injury and poisoning.

The hospital separations data do not include episodes of non-admitted patient care given in outpatient clinics or emergency departments. Patients in these settings may be admitted later, with the care provided to them as admitted patients being included in the NHMD.

The following care types were excluded when undertaking the analysis: 7.3 (newborn – unqualified days only), 9 (organ procurement – posthumous) and 10 (hospital boarder).

For more information on the NHMD, see National Hospitals Data Collection.

National Non-admitted Patient Database

The Non-admitted patient database holds data on non-admitted patients service events in public hospital outpatient clinics. This includes selected patient characteristics; the type of outpatient clinic; whether the episode was an individual or a group service event; the source of the request for service; the service delivery setting; the service delivery mode and the principal source of funding.

For more information on the National Non-admitted Patient Database, see National Hospitals Data Collection.

National Health Survey

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2017–18 National Health Survey (NHS) was conducted by the ABS to obtain national information on the health status of Australians, their use of health services and facilities, and health-related aspects of their lifestyle. The NHS collected self-reported data on whether a respondent had 1 or more long-term health conditions; that is, conditions that lasted, or were expected to last, 6 months or more. These data are used in this report to estimate the prevalence of arthritis. When interpreting data from the 2017–18 NHS, some limitations need to be considered:

- Much of the data is self-reported and therefore relies heavily on respondents knowing and providing accurate information.

- The survey is community-based and does not include information from people living in nursing homes or otherwise institutionalised.

- Residents of very remote areas and discrete Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities were excluded from the survey. This is unlikely to affect national estimates but will impact prevalence estimates by remoteness.

Further information can be found in National Health Survey: First results, 2017–18 (ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001).

National Integrated Health Services Information Analysis Asset

The National Integrated Health Services Information Analysis Asset (NIHSI AA) (version 1.0) is an enduring linked data asset. Data from NIHSI AA were used to explore linked hospitalisation data for juvenile arthritis in Australia. Data is held at unit record level and includes health services data from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2019. The admitted patient care dataset within NIHSI AA was included in this report. The admitted patient care dataset includes unit record level admitted patient episode data, which is drawn from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). Records are provided from all public hospitals in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, and Australian Capital Territory from July 2010 to June 2019. In addition, private hospitals data are included (where available) for Victoria from July 2010 to June 2017, and for Queensland and Australian Capital Territory from July 2010 to June 2019. Analysis by hospital sector is not included in this report.

In this report, age is taken from the patient’s age at their separation from hospital.

The admitted patient care dataset was used for diagnosis data (Box 13).

Box 13: ICD-10-AM

Diagnosis, intervention and external cause data are reported to the NHMD by all states and territories using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) and the Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI). The Australian Coding Standards (ACS) are designed to be used in conjunction with the ICD-10-AM and ACHI to support sound coding convention.

The hospital episodes reported were coded according to the applicable ICD-10-AM edition for the following years:

- 2010–11 to 2012–13: ICD-10-AM 7th edition

- 2013–14 to 2014–15: ICD-10-AM 8th edition

- 2015–16 to 2016–17: ICD-10-AM 9th edition

- 2017–18 to 2018–19: ICD-10-AM 10th edition.

Methods (rates and average annual change)

A rate is defined as the number of events over a specified period (for example, a year) divided by the total population at risk of the event. Crude hospitalisation rates were used in this report, and the denominator (or total population at risk) was estimated using the resident population (ERP) values as of 31 December for the given year (for example, crude rates for 2000–01 used the December 2000 population). The estimated count of people in Australia from the 2021 Census was used as the denominator for the rate of arthritis calculated using Census 2021 data.

Average annual changes in this report have been calculated using the first and last time points in a series, assuming nothing about the variation in between. For example, the average annual change (AAC) change in juvenile arthritis hospitalisations between 2000–01 and 2020–21 was calculated as AAC = 100 × ((EV/SV) ^ (1/T) − 1), where:

- AAC = Average annual change between 2000–01 and 2020–21

- Ending Value (EV) = Hospitalisations in 2020–21

- Starting Value (SV) = Hospitalisations in 2000–01

- Time (T) = The number of time steps between the start and end value (that is, 21 years).

Acknowledgements

The Juvenile arthritis report was produced by staff from the Chronic Conditions Unit at the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

Valuable input was received from AIHW's Musculoskeletal Expert Advisory Group, whose members at the time of producing this report were: Lyn March (Chair), Mellick Chehade, Flavia Cicuttini, Peter Ebeling, Mark Friswell, Tiffany Gill, Paul Hodges, Rebecca James, Chris Maher, Pam Webster, and from Ruth Colagiuri and Stephen Colagiuri from the Juvenile Arthritis Foundation Australia (JAFA).

The Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care funded this report and the valuable comments received by individuals from the Department are also acknowledged.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2012) Microdata: Australian Health Survey, National Health Survey, 2011–12, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 1 June 2023.

ABS (2015) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2014–15, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 1 June 2023.

ABS (2018a) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 24 January 2023.

ABS (2018b) National Health Survey: first results, 2017–18, ABS website, accessed 7 February 2022.

ABS (2019) National Health Survey: users’ guide, 2017–18, ABS website, accessed 18 February 2022.

ABS (2021) Type of long-term health condition (LTHP), ABS website, accessed 27 January 2023.

ABS (2022a) Comparing ABS long-term health conditions data sources, ABS website, accessed 8 December 2022.

ABS (2022b) National Health Survey: First results methodology, ABS website, accessed 9 May 2023.

ABS (2022c) Health Census, ABS website, accessed 8 December 2022.

Agency for Clinical Innovation New South Wales (2013) Model of Care for the NSW Paediatric Rheumatology Network, Agency for Clinical Innovation New South Wales website, accessed 24 November 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2019a) Medication use for ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and juvenile arthritis 2016–17, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 8 March 2023.

AIHW (2019b) Admitted patient care 2017–18, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 16 May 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 December 2022.

AIHW (2022b) Australia's hospitals at a glance, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 3 March 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Diabetes: Australian facts, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 May 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2022.

AIHW (2023c) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2022.

Al-Mayouf S, Mutairi M, Bouayed K, Habjoka S, Hadef D, Lofty H, Scott C, Sharif E and Tahoun N (2021) Epidemiology and demographics of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Africa and Middle East, Paediatric Rheumatology, 19(1):166. doi.org/10.1186/s12969-021-00650-x.

Australian Rheumatology Association (ARA) (2017) NSAIDs, ARA, accessed 6 December 2022.

ARA (2019) Tocilizumab, ARA, accessed 6 December 2022.

ARA (2023) ARA Rheumatology Workforce Report, ARA, accessed 7 March 2023.

Arthritis Foundation (2023) DMARDS, Arthritis Foundation, accessed 8 December 2022.

Barut K, Adrovic A, Şahin S, Kasapçopur Ö (2017) Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, Balkan Medical Journal, 5;34(2):90–101, doi:10.4274/balkanmedj.2017.0111.

Ben–Ezra D, Cohen E and Behar-Cohen F (2007) Uveitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A cohort study, Clinical Ophthalmology, 1(4):513–518.

Boros C and Whitehead B (2010) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Australian Family Physician, 39(9):630-6, accessed 26 January 2023.

Bouaddi I, Rostom S, El Badri D, Hassani A, Chkirate B, Amine B and Najia H (2013) Impact of juvenile idiopathic arthritis on schooling, BMC Pediatrics, 13(2), doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-2.

Bray K (2022) Rheumatologist shortage likely to get worse, Rheumatology Republic, accessed 17 October 2022.

Buchman A (2001) Side effects of corticosteroid therapy, Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 33(4):289–294, doi.org/10.1097/00004836-200110000-00006.

Clarke S, Sen E and Ramanan A (2016) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis, Paediatric Rheumatology, 14(1):27, doi.org/10.1186/s12969-016-0088-2.

Cleary A, Murphy H and Davidson J (2003) Intra-articular corticosteroid injections in juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(3):192, doi.org/10.1136/adc.88.3.192.

Costello R, McDonagh J, Hyrich K and Humphreys J (2022) Incidence and prevalence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the United Kingdom, 2000-2018: results from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, Rheumatology, 61(6):2548–2554, doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab714.

Davies K, Cleary G, Foster H, Hutchinson E and Baildam E (2010) BSPAR Standards of Care for children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, British Society for Rheumatology, 49 (7):1406–1408, doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep460.

Demir F, Eroglu N, Bahadir A and Kalyoncu M (2019) A case of acute lymphoblastic leukemia mimicking juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Northern Clinics of Istanbul, 6(2):184–188, doi.org/10.14744/nci.2018.48658.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2015) Primary care, Department of Health and Aged Care website, accessed 29 November 2022.

Fair D, Rodriguez M, Knight A and Rubinstein T (2019) Depression and anxiety in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: current insights and impact on quality of life, a systematic review, Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews, 11:237–252, doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S174408.

Falvey S, Shipman L, Ilowite N and Beukelman T (2017) Methotrexate-induced nausea in the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal, 15(1):52, doi.org/10.1186/s12969-017-0180-2.

Furness L, Riley P, Wright N, Banka S, Eyre S, Jackson A and Briggs T (2022) Monogenic disorders as mimics of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Paediatric Rheumatology Online Journal, 20(1):44, doi.org/10.1186/s12969-022-00700-y.

Horneff G, Borchert J, Heinrich R, Kock S, Klaus, P, Dally H, Hagemann C, Diesing J and Schonfelder T (2022) Incidence, prevalence, and comorbidities of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Germany: a retrospective observational cohort health claims database study, Paediatric Rheumatology, 20(1):100, doi.org/10.1186/s12969-022-00755-x.

Horton D and Shenoi S (2019) Review of environmental factors and juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews, 11(1):253–267, doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S165916.

Jeon Y, Essue B, Jan S, Wells R and Whitworth J (2009) Economic hardship associated with managing chronic illness: a qualitative inquiry, BMC Health Services Research, 9, 182, doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-182.

Li J, Zhu Y and Guo G (2022), Enthesitis-related arthritis: the clinical characteristics and factors related to MRI remission of sacroiliitis, BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 23(1):1054, doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-06028-8.

Laila K, Haque M, Islam M, M Taludker, Rahman S (2016) Impact of juvenile idiopathic arthritis on school attendance and performance, American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 4(6):185–190, 10.11648/j.ajcem.20160406.15.

Manners P and Bower C (2002) Worldwide prevalence of juvenile arthritis why does it vary so much?, The Journal of Rheumatology, 29(7):1520–1530.

Maresova K (2011) Secondary osteoporosis in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Journal of osteoporosis, Journal of Osteoporosis, doi.org/10.4061/2011/569417.

Min M, Edwards S, Gibson S, Crotti T and Boros C (2020) Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis in South Australia, Research Square, doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-88109/v1.