Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024) Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 October 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoporosis

MLA

Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 17 June 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoporosis

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024 [cited 2024 Oct. 22]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoporosis

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2024, Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures, viewed 22 October 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoporosis

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

This article is part of Chronic musculoskeletal conditions

Page highlights

- Osteoporosis is a chronic condition defined by low bone mineral density, which increases the risk of fractures.

- Osteopenia refers to bone-mineral density that is lower than normal but not low enough to be classified as osteoporosis.

Around 853,600 (3.4%) people in Australia were estimated to be living with osteoporosis or osteopenia in 2022. The true prevalence, including undiagnosed cases, is likely to be higher than this.

- 29% of fall burden was attributed to low bone mineral density, equivalent to 0.4% of total disease burden in 2018.

- In 2018–19, an estimated $1.2 billion or 29% of expenditure for falls was attributed to low bone mineral density, representing 1.9% of total health system expenditure.

- Osteoporosis contributed to 2,659 deaths or 10.2 deaths per 100,000 population in 2022, representing 1.4% of all deaths.

Treatment and management of osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures

- In 2021–22, there were 9,500 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoporosis (89 hospitalisations per 100,000 population) for people aged 45 and over.

- There were 105,000 hospitalisations for minimal trauma fractures in people aged 45 and over in 2021–22, 28% of these were hip fractures.

- The rate of minimal trauma hip fractures decreased consistently from 2017–18, possibly reflecting measures to reduce risk factors and prevent falls.

In 2022, 79% of people estimated to be living with osteoporosis were also living with one or more other chronic conditions – the top 3 comorbidities were arthritis (44%), back problems (35%) and mental and behavioural conditions (34%).

What is osteoporosis?

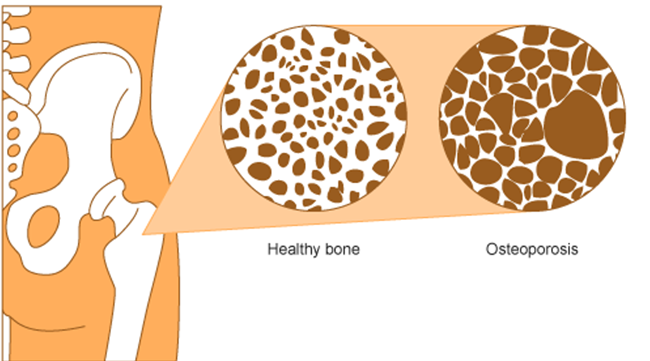

Osteoporosis (meaning 'porous bones') is a condition that arises when bones become less dense, lose minerals such as calcium and are more fragile (Figure 1) (Health Direct 2023; Healthy Bones Australia 2023).

Minimal trauma fractures (broken bones) are a major feature of osteoporosis and are fractures that that occur following little or no trauma. Fractures due to osteoporosis can result in chronic pain, disability, loss of independence and premature death (Bliuc et al. 2013).

Figure 1: Visual representation of a healthy bone and bone with osteoporosis

Osteopenia is a condition where bone density is lower than normal but not low enough to be classified as osteoporosis. It can progress to osteoporosis.

Diagnosis of osteoporosis requires an assessment of bone mineral density (BMD). The most commonly used technique used for this is a specialised X-ray known as a 'Dual energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) scan' (IOF 2017). Scan results are expressed as T‑scores which are compared to an average score of young healthy adults for diagnosis (Table 1) (WHO 1994).

| Normal | Osteopenia | Osteoporosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-Score | 1 to -1 | 1 to -2.5 | -2.5 or lower |

Source: WHO Study Group 1994.

Because osteoporosis has no overt symptoms, it is often not diagnosed until a fracture occurs. It is therefore difficult to determine the true prevalence of the condition and reported prevalence is likely to be an underestimation.

What causes osteoporosis and osteopenia?

Osteoporosis is largely a preventable disease. Risk factors associated with the development of osteoporosis include increasing age, being female, family history of the condition, low vitamin D levels, low intake of calcium, low body weight, smoking, excess alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, long-term corticosteroid use and reduced oestrogen level (Ebeling et al. 2013).

Primary prevention of osteoporosis involves taking calcium and vitamin D supplements, behaviour modification such as regular weight-bearing and resistance exercise, keeping alcohol intake low and not smoking, and fall reduction strategies, such as addressing vision impairment or making home modifications (RACGP 2018).

The goal of the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis is to maintain bone density and reduce a person’s overall fracture risk (RACGP 2018).

How common is osteoporosis?

Around 853,600 (3.4%) people in Australia were estimated to be living with osteoporosis or osteopenia, according to self-reported data in the 2022 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS) (ABS 2023).

Note: Unless otherwise stated, crude rates are presented for prevalence in this report and as such, these rates have not been adjusted to account for differences in the age structures of different populations. Care should therefore be taken before making comparisons between populations using these data.

In 2022, the prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia collectively:

- increased substantially with increasing age, from 0.7% of people aged 35–44, to 17% of people aged 75 and over

- was higher among women compared with men (5.5% and 1.1%, respectively)

- was highest for women aged 75 and over (26%)

- changed little by remoteness or level of disadvantage (also known as socioeconomic area) (Figure 2) (ABS 2023).

After adjusting for different population age structures over time, the prevalence of osteoporosis increased from 1.6% in 2001 to 2.7% in 2022 (ABS 2023).

Figure 2: Prevalence of osteoporosis, by age and sex, over time (2001 to 2022), by population group, 2022

This figure shows that the prevalence of osteoporosis or osteopenia was almost 5 times as high for females compared with males for those aged 55 to 74.

Prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) uses ‘First Nations people’ to refer to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people in this report.

Around 18,900 (2.3%) First Nations people were estimated to be living with osteoporosis in 2018–19, based on the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health survey (NATSIHS), up from 1.5% in 2012–13 (ABS 2019b).

Impact of osteoporosis

Quality of life can be severely compromised for people with osteoporosis, particularly if they fall and sustain a fracture. Fractures can make it hard for people to write, type, prepare meals, walk or perform personal care tasks and manage household chores.

Measures of impact presented in this section include burden of disease, health expenditure and mortality data.

Burden of disease

In 2018, falls represented 1.5% of total disease burden (also known as disability adjusted life years or DALY) in Australia. Almost a third (29%) of fall burden was attributed to low bone mineral density or 0.4% of total disease burden in Australia.

Note that this does not represent the complete burden of low bone mineral density, just the proportion associated with falls. This estimate reflects the amount of burden for falls that could have been avoided if no one in Australia had low bone mineral density.

Variation by age and sex

Burden attributed to low bone mineral density was estimated for people aged 35 and over. The rate of burden:

- increased substantially with increasing age, from 9.3 DALY per 100,000 population for people aged 35–44, to 1,500 DALY per 100,000 population for people aged 85 and over

- was 1.5 times higher among females compared with males.

Trends over time

After adjusting for different population age structures over time, the rate of fall burden attributed to low bone mineral density increased by 16% (from 0.59 to 0.69 DALY per 1,000 population), which is equivalent to a 1.0% per year increase on average between 2003 and 2018.

For more information, see the Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden (AIHW 2021).

Health system expenditure

In 2018–19, an estimated 29% of expenditure for falls was attributed to low bone mineral density, equating to $1.2 billion, or 1.9%, of total health system expenditure.

For more information, see Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors (AIHW 2022).

How many deaths were associated with osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis was recorded as an underlying and/or associated cause for 2,659 deaths or 10 deaths per 100,000 population in Australia in 2022. This represented 1.4% of all deaths and 25% of all musculoskeletal deaths in 2022. Note that this does not include osteopenia.

Osteoporosis was the underlying cause for 202 deaths (7.6% of all osteoporosis deaths) and an associated cause only, for 2,457 deaths (around 92% of all osteoporosis deaths).

Variation by age and sex

In 2022, osteoporosis mortality (as the underlying and/or associated cause), in comparison to all deaths, was more common amongst:

- older people (91% of osteoporosis deaths were among people aged 75 and over, compared with 68% of total deaths)

- females (80% of osteoporosis deaths were among females, compared with 48% of total deaths) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Age distribution for osteoporosis mortality, by sex, 2012 to 2022

This figure shows that death rates due to osteoporosis increased after the age group 65–69 and were highest for people aged 85 and over in 2022.

Trends over time

After adjusting for different population age structures over time, mortality rates (number of deaths per 100,000 population) for osteoporosis (as the underlying and/or associated cause) between 2012 and 2022:

- remained fairly stable for males and females (males: 3.2 and 3.4 and females 9.5 and 9.6 in 2012 and 2022, respectively)

- were between 2.6 and 3.2 times higher for females compared with males for all years (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Trends over time for osteoporosis mortality, 2012 to 2022

This figure shows that between 2012 and 2022, death rates due to osteoporosis were highest in 2022 and lowest in 2013.

Variation between population groups

In 2022, after adjusting for age differences, osteoporosis mortality rates (underlying and/or associated cause) changed little by remoteness area or level of disadvantage (also known as socioeconomic area):

- 7.2 deaths per 100,000 population for people living in Major cities compared with 6.4 deaths per 100,000 for people living in Outer regional areas

- 7.5 deaths per 100,000 population for people living in areas of most disadvantage (lowest socioeconomic areas) and 6.6 deaths per 100,000 population for people living in the least disadvantaged areas (highest socioeconomic areas).

Treatment and management of osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures

Treatment recommendations for osteoporosis are often based on an estimate of a person’s risk of breaking a bone in the next 10 years using information such as a bone density test. If the risk is not high, treatment might not include medication and might focus instead on modifying risk factors for bone loss and falls.

What medicines are used to treat osteoporosis?

Once a patient has experienced a fracture, bone protection medicine is indicated for individuals with a significantly increased risk of further fractures (Ebeling et al. 2023).

There is a diverse range of medications available to manage osteoporosis. Treatment selection is guided by factors such as sex, menopausal status, medical history, whether it is for primary or secondary fracture prevention, patient preference and eligibility for government subsidy (Bell et al. 2012).

For more information on medications recommended for osteoporosis, see Chapter 14 of Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (RACGP 2018) and the Osteoporosis treatment and bone health fact sheet (Healthy Bones Australia 2021).

What role do hospitals play in treating osteoporosis?

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that in 2021–22, there were 10,100 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoporosis, and 32,500 hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of osteoporosis, representing 0.3% of all hospitalisations. Note that this does not include osteopenia.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoporosis for people aged 45 and over, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of osteoporosis, and all ages.

For people aged 45 and over, in 2021–22:

- there were 9,500 osteoporosis hospitalisations, representing 0.1% of all age-specific hospitalisations in Australia, and 89 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- osteoporosis accounted for 71,600 bed days, representing 0.3% of all age-specific bed days

- 65% of osteoporosis hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 11 days (Figure 5).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, osteoporosis hospitalisations rates:

- increased substantially with age (10 hospitalisations per 100,000 population aged 45–49, compared with 480 hospitalisations per 100,000 population aged 85 and over)

- were 2.8 times more common among females compared with males (130 and 46 hospitalisations per 100,000 population aged 45 and over, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Age distribution for osteoporosis hospitalisations, by sex, 2021–22

This figure shows that there were 2,600 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoporosis for people aged 85 and over in 2021-22.

Trends over time

From 2011–12 to 2021–22, for osteoporosis hospitalisations among people aged 45 and over:

- the rate varied between a minimum of 65 hospitalisations per 100,000 population in 2014–15 and a maximum of 89 hospitalisations per 100,000 population in 2021–22

- the proportion of overnight stays increased from 50% to 65%

- the average length of overnight stays remained relatively stable, ranging between 10.3 and 11.6 days (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Trends over time for osteoporosis hospitalisations, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between 2011–12 to 2021–22, the number of hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoporosis increased from 6,400 to 10,100.

Hospitalisations for minimal trauma fractures

People with osteoporosis can be hospitalised for a range of reasons, including minimal trauma fractures. Minimal trauma fractures generate substantial costs to the community, including direct costs in terms of hospital treatment.

Osteoporosis is rarely observed before the age of 45, therefore data below are presented for people over this age. The data presented below also exclude hospitalisations where the patient was transferred from another hospital, to more accurately represent the number of these injuries that resulted in hospital admission. For people aged 45 and over, in 2021–22:

- there were 105,000 minimal trauma fracture events resulting in hospitalisation with fracture as the principal diagnosis, representing 980 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- hip was the most common fracture site, accounting for 28% of minimal trauma fracture hospitalisations.

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, for people aged 45 and over, minimal trauma fracture hospitalisations:

- increased substantially with increasing age (165 hospitalisations per 100,000 population aged 45–49 compared with 6,000 hospitalisations per 100,000 population for people aged 85 and over)

- were 2.1 times more common among females compared with males (1,300 and 620 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Trends over time for minimal trauma fracture hospitalisations, by fracture site, age and sex, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows minimal trauma fracture hospitalisations for persons aged 45 and over were higher for females for all fracture sites compared with males.

Hospitalisations for minimal trauma hip fractures

Minimal trauma hip fracture is one of the most serious and debilitating outcomes of osteoporosis (Ip et al. 2010). Hip fractures are serious medical emergencies that require time-critical care, often require hospitalisation and surgery, and may be a source of ongoing pain and disability. These fractures have a considerable impact on individuals, the community and the Australian health system (Watts et al. 2013).

Note that the data below exclude hospitalisations where the patient was transferred from another hospital, to more accurately represent the number of these injuries that resulted in hospital admission.

For people aged 45 and over, in 2021–22, there were 29,000 minimal trauma hip fracture events resulting in hospitalisation with hip fracture as the principal diagnosis (270 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, for people aged 45 and over, minimal trauma hip fracture hospitalisations:

- increased substantially with increasing age (10 hospitalisations per 100,000 population aged 45–49, compared with 2,200 hospitalisations per 100,000 population aged 85 and over)

- were 1.8 times more common among females compared with males (350 and 190 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Age distribution for minimal trauma fracture hospitalisations, by sex, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows minimal trauma fracture hospitalisations for people aged 85 and over were higher for hip fractures compared with other fracture sites.

Trends over time

Between 2015–16 and 2021–22, the minimal trauma hip fracture hospitalisation rate for people aged 45 and over increased to a high of 300 hospitalisations per 100,000 population in 2017–18 and decreased consistently thereafter. This pattern may reflect measures implemented over time to reduce risk factors and prevent falls among the at-risk population (RACGP 2018).

Using linked data to monitor hip fracture care pathways

Linked data can provide a more complete picture of patient outcomes following a hip fracture and allows for counts of people to be presented rather than separations. It also avoids double counting due to hospital transfers or changes in care type. Findings from a recent linked data report on hip fractures are provided in Box 1.

Box 1: Monitoring hip fracture care pathways using linked data

Analysis of linked hospitals, death and residential aged care data found that among people aged 45 and over:

- there were around 16,300 to 17,100 first hip fracture patients each year, with a total of 67,200 first hip fracture patients between July 2013 and June 2017

- less than half of first hip fracture patients (43%) who were alive one year after their hip fracture had at least one prescription dispensed for an osteoporosis-related medication in the year after their hip fracture

- the median length of stay in the acute phase of care continuous from the time of hip fracture was 8 days, compared with 20 days when all care following the hip fracture was included (including acute, rehabilitation and any other care in the same hospital stay)

- over the year following first hip fracture, 3.0% of surgical patients were hospitalised with a second hip fracture

- 26% of first hip fracture patients died within one year of admission to hospital.

For more information, see Hip fracture care pathways in Australia (AIHW 2023).

Comorbidities of osteoporosis

People living with osteoporosis often also live with other chronic conditions, known as ‘comorbidity’. According to the NHS, in 2022, an estimated 674,000 (79%) people who were living with osteoporosis also had one or more other chronic conditions – the top 3 comorbidities were arthritis (44%), back problems (35%) and mental and behavioural conditions (34%) (Figure 9) (ABS 2023).

Figure 9: Number of selected chronic conditions and types of comorbidity in people with osteoporosis, 2022

This figure shows that 20% of people estimated to be living with osteoporosis reported not having any of the other selected chronic conditions.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18, ABS website, accessed 28 April 2023.

ABS (2019a) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, AIHW analysis of detailed microdata, accessed 28 April 2023.

ABS (2019b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: 2018–19, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 28 April 2023.

ABS (2023) National Health Survey 2022, ABS website, accessed 1 February 2024

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 6 September 2023.

AIHW (2022) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 6 September 2023.

AIHW (2023) Hip fracture care pathways in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 24 November 2023.

Bell JS, Blacker N, Edwards S, Frank O, Alderman CP, Karan L, Husband A and Rowett D (2012) ‘Osteoporosis: Pharmacological prevention and management in older people’, Australian Family Physician, 41(3):110-118, doi: 10.3316/informit.002859086807515.

Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA and Center JR (2013) ‘Compound risk of mortality following osteoporotic fracture and refracture in elderly women and men’, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 28(11):2317–2324, doi:10.1002/jbmr.1968.

Ebeling PR, Daly RM, Kerr DA and Kimlin M (2013) ‘Building healthy bones throughout life: an evidence-informed strategy to prevent osteoporosis in Australia’, Medical Journal of Australia, 199(S7):1–46, doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2013.tb04225.x.

Health Direct (2023) Osteoporosis, Health Direct website, accessed 7 June 2023.

Healthy Bones Australia (2023) About Bones, Healthy Bones Australia website, accessed 30 May 2023.

Healthy Bones Australia (2021) Osteoporosis & bone health fact sheet, Healthy Bones Australia website, accessed 13 September 2023.

IOF (International Osteoporosis Foundation) (2017) Diagnosing Osteoporosis, International Osteoporosis Foundation website, accessed 30 January 2020.

Ip TP, Leung J and Kung AWC (2010) ‘Management of osteoporosis in patients hospitalized for hip fractures’, Osteoporosis International, 21(4):S605–S614, doi:10.1007/s00198-010-1398-8.

RACGP (2018) Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (9th edition), RACGP website, accessed 30 May 2023.

Watts JJ, Abimanyi-Ochon J and Sanders KM (2013) Osteoporosis costing all Australians: A new burden of disease analysis–2012 to 2022, Osteoporosis Australia website, accessed 17 March 2020.

WHO (World Health Organization) (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group [meeting held in Rome from 22 to 25 June 1992], WHO Technical Report Series 843, WHO, Switzerland.