Osteoarthritis

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Osteoarthritis, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 25 April 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Osteoarthritis. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoarthritis

MLA

Osteoarthritis. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 14 December 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoarthritis

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Osteoarthritis [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Apr. 25]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoarthritis

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Osteoarthritis, viewed 25 April 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoarthritis

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Page highlights

Osteoarthritis is characterised by the breakdown of the cartilage that overlies the ends of bones in joints. It mostly affects the knees, hands, and hips.

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in Australia – an estimated 2.2 million (9.3%) people reported having osteoarthritis in 2017–18.

- People with osteoarthritis had around double the rates of ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health (32%), ‘moderate’ to ‘very high’ psychological distress (46%) and ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain (58%) compared with those without the condition.

- Osteoarthritis accounted for 2.5% of total disease burden and 20% of the total burden of disease due to musculoskeletal conditions in 2023.

- In 2020–21, an estimated $4.3 billion was spent on the treatment and management of osteoarthritis, representing 2.9% of total health system expenditure and 29% of expenditure for all musculoskeletal conditions.

- Osteoarthritis contributed to 2,198 deaths or 6.0 deaths per 100,000 population in 2021, representing 1.3% of all deaths.

Treatment and management of osteoarthritis

- In 2021–22, there were 242,000 hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoarthritis (940 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).

- In 2021–22, 53,500 knee replacements (210 per 100,000 population) and 35,500 hip replacements (140 per 100,000 population) were performed to treat osteoarthritis.

Comorbidities of osteoarthritis

Eight of 9 comorbidities analysed were significantly more common among people with osteoarthritis compared to those without – the top 3 comorbidities were back problems (38%), mental and behavioural conditions (31%), and osteoporosis or osteopenia (22%).

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a chronic condition characterised by the breakdown of the cartilage that overlies the ends of bones in joints, and usually gets worse over time. It mostly affects the knees, hands, and hips, but can also affect other joints such as the spine and ankles.

As osteoarthritis progresses, it can become difficult to perform everyday tasks. At first, pain is felt during and after activity, but as the condition worsens, pain may be felt during minor movements or even at rest. Affected joints may also become swollen and tender which can affect fine motor skills.

Several factors can contribute to the onset and progression of osteoarthritis (Chapman and Valdes 2012), including:

- being female

- genetic factors

- excess weight

- joint misalignment

- joint injury or trauma (such as dislocation or fracture)

- repetitive joint-loading tasks (for example, kneeling, squatting and heavy lifting).

How common is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis in Australia. An estimated 2.2 million (9.3%) people in Australia reported having this condition, according to the 2017–18 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS) (ABS 2019). This represented 62% of people with any form of arthritis, excluding gout.

For more information about other forms of arthritis, see All arthritis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Gout, and Juvenile arthritis.

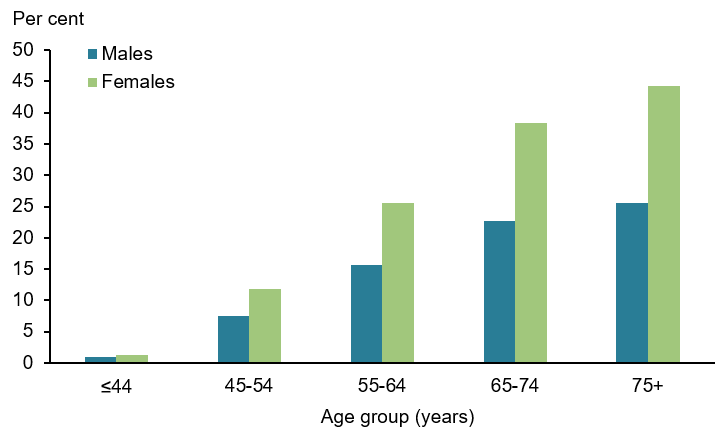

Prevalence by age and sex

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, osteoarthritis:

- affects people of all ages, but 93% of cases occurred among people aged 45 and over, with the prevalence being 22% for this age group

- prevalence increased substantially with age, from 9.7% among people aged 45–54, to 36% of those aged 75 and over

- was more common among females compared with males (12% and 6.8%, respectively, or 10% and 6.1%, respectively, after adjusting for age) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence of self-reported osteoarthritis, by age and sex, 2017–18

Note: Refers to people who self-reported that being told that they had osteoarthritis (current and long term) by a doctor or nurse and people who self-reported having osteoarthritis.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) analysis of ABS 2019 (Osteoarthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 1.1).

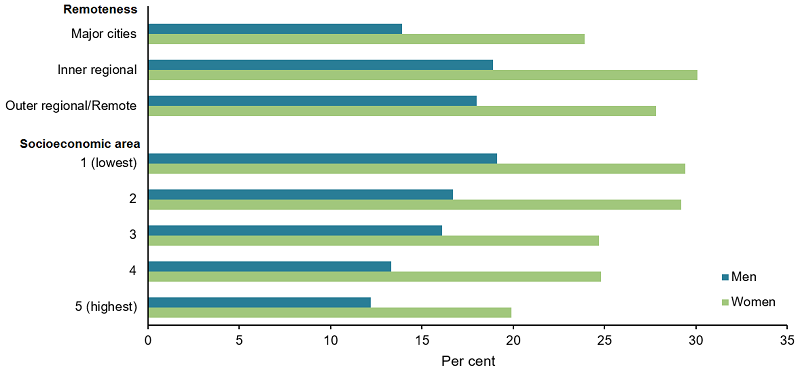

Variation between population groups

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, for people aged 45 and over, the prevalence of osteoarthritis, after adjusting for age, was:

- slightly lower in Major cities (19%), compared with Inner regional (25%) and Outer regional/Remote (23%) areas

- higher for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (25%) compared with people in the highest socioeconomic areas (16%)

- over 1.5 times higher for women compared with men for all regions and socioeconomic areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Osteoarthritis prevalence among people aged 45 and over, by remoteness and socioeconomic area, 2017–18

Note: Age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Osteoarthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 1.2).

Impact of osteoarthritis

How does osteoarthritis affect quality of life?

Osteoarthritis can have a profound impact on every aspect of a person's life. Ongoing pain, physical limitations and depression can affect an individual's ability to engage in social, community and occupational activities (Briggs et al. 2016).

People with osteoarthritis commonly experience anxiety, depression and other mental health issues. Pain, physical limitations, poor treatment outcomes and increased pharmacotherapy can impact a person’s mental health and, consequently, their quality of life (Sharma et al. 2016).

Osteoarthritis can also impact on a person’s physical health, as joint pain and physical limitations are major symptoms of osteoarthritis. Older people with osteoarthritis can also be more prone to falls compared with those without osteoarthritis. This increased risk is due to a number of factors caused by osteoarthritis, such as decreased physical activity, joint instability, medication use and pain (Cooper et al. 2010).

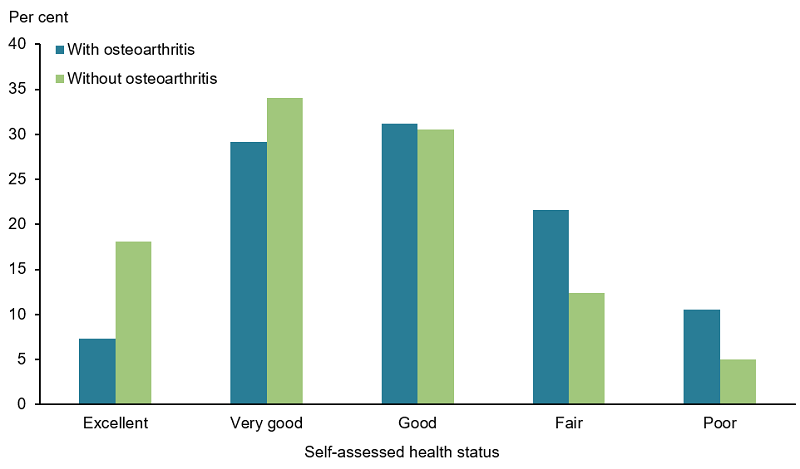

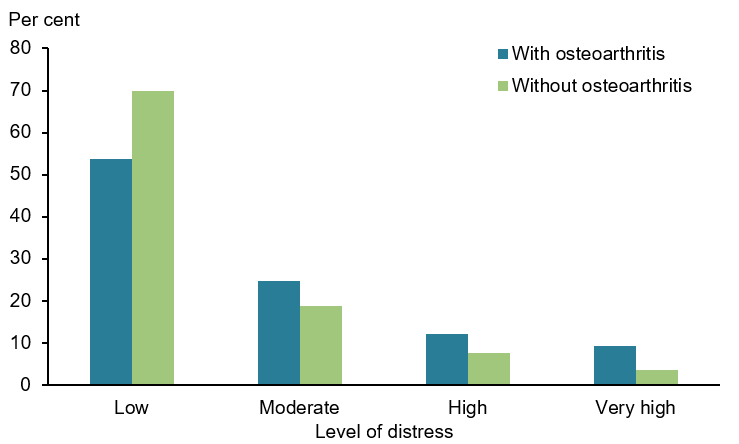

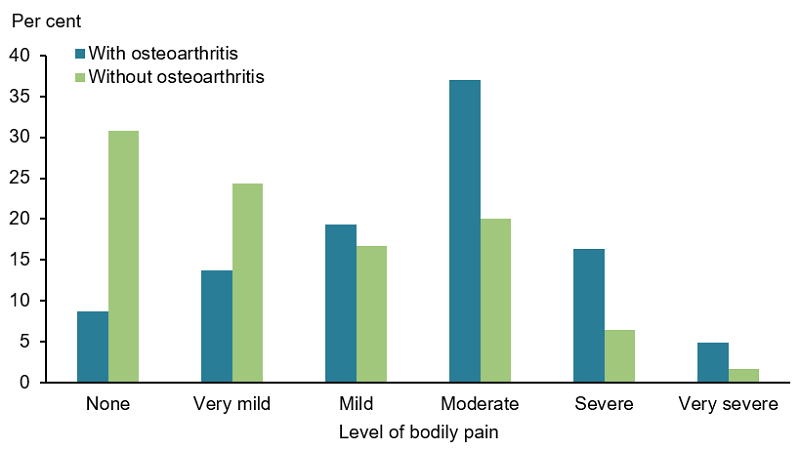

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, after adjusting for age, people aged 45 and over with osteoarthritis were:

- less likely to describe their health as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’, and 1.9 times as likely to report ‘fair’ to ‘poor’ health, compared with those without osteoarthritis (32% and 17%, respectively) (Figure 3)

- 1.5 times as likely to experience ‘moderate’ to ‘very high’ levels of psychological distress compared with people without osteoarthritis (46% and 30% respectively) (Figure 4)

- 2.1 times as likely to experience ‘moderate’ to ‘very severe’ bodily pain compared with those without osteoarthritis (58% and 28%, respectively) (Figure 5)

- 2.2 times as likely to describe their pain as having a ‘moderate’ to ‘extreme’ interference with their normal work during the last 4 weeks, compared with people without osteoarthritis (48% and 22%, respectively).

Figure 3: Self-assessed health of people aged 45 and over with and without osteoarthritis, 2017–18

Note: Age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Osteoarthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 2.1).

Figure 4: Psychological distress(a) experienced by people aged 45 and over with and without osteoarthritis, 2017–18

(a) Psychological distress is measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), which involves 10 questions about negative emotional states experienced in the previous 4 weeks. The scores are grouped into Low: K10 score 10–15, Moderate: 16–21, High: 22–29, Very high: 30–50.

Note: Age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Osteoarthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 2.2).

Figure 5: Pain(a) experienced by people aged 45 and over with and without osteoarthritis, 2017–18

(a) Body pain experienced in the last 4 weeks prior to interview

Note: Age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Osteoarthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 2.3).

Burden of disease

What is burden of disease?

Burden of disease is measured using the summary metric of disability-adjusted life years (DALY, also known as the total burden). One DALY is one year of healthy life lost to disease and injury. DALY caused by living in poor health (non-fatal burden) are the ‘years lived with disability’ (YLD). DALY caused by premature death (fatal burden) are the ‘years of life lost’ (YLL) and are measured against an ideal life expectancy. DALY allows the impact of premature deaths and living with health impacts from disease or injury to be compared and reported in a consistent manner (AIHW 2022a).

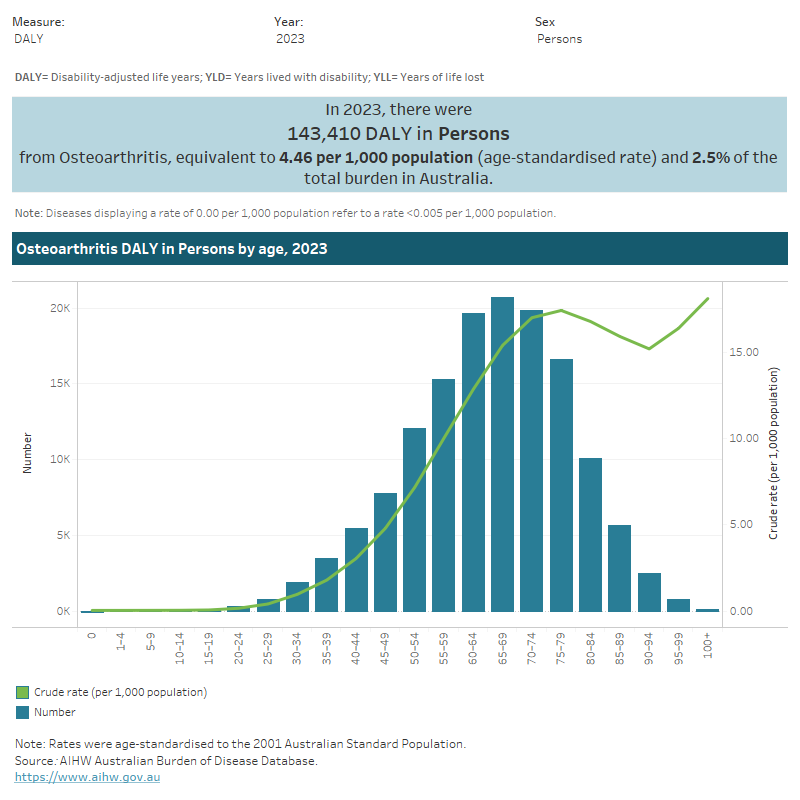

In 2023, osteoarthritis accounted for 2.5% of total disease burden (DALY); 4.7% of non-fatal burden (YLD), and almost no fatal burden (less than 1%) (YLL). Within the musculoskeletal disease group, osteoarthritis accounted for 19.8% of total burden (DALY); 20.3% of non-fatal burden (YLD); and 2.8% of fatal burden (YLL) (AIHW 2023a).

Variation by age and sex

In 2023, the rate of burden from osteoarthritis:

- was 1.8 times as high for females compared with males (6.9 and 3.9 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- was less than 0.1 DALY per 1,000 population for age groups below 20–24 years, and then rose steeply with age, reaching 17.4 DALY per 1,000 population for 75–79.

Figure 6: Burden of disease due to osteoarthritis by age, sex and year

This figure shows that the rate of non-fatal burden due to osteoarthritis was higher for females than for males in 2023.

Trends over time

Between 2003 and 2023, the age standardised rate of osteoarthritis burden increased by 27% (from 3.5 to 4.5 DALY per 1,000 population) – or 1.2% per year on average. Osteoarthritis burden was largely non-fatal and remained similar over time (from 99.2% in 2003 to 99.6% YLD in 2023).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023.

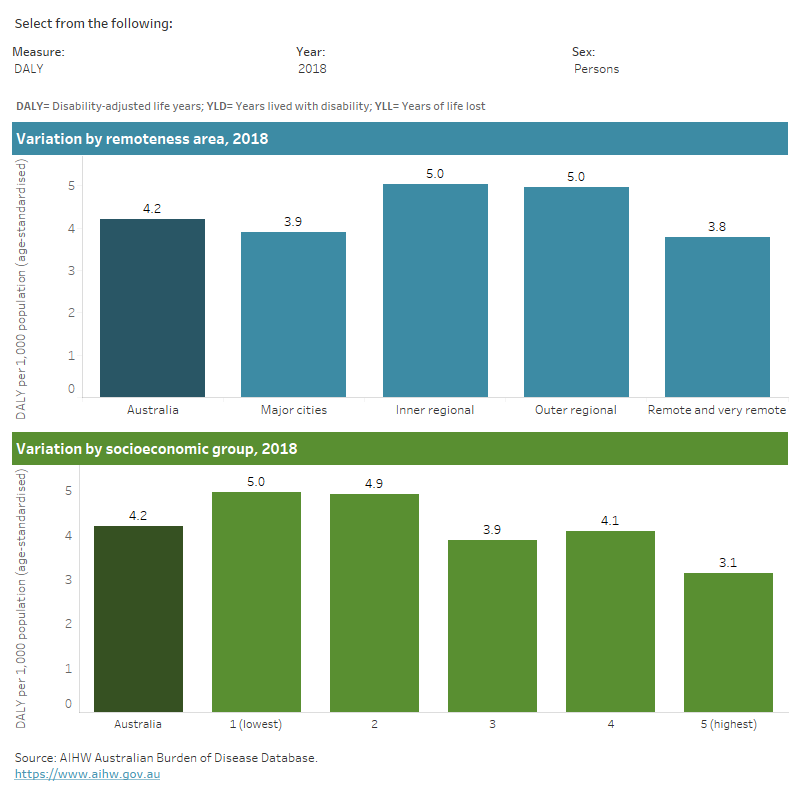

Variation between population groups

In 2018, the age standardised rate of osteoarthritis burden:

- was highest for people living in Inner regional and Outer regional areas (each 5.0 DALY per 1,000 population) and lowest for people living in Remote and very remote areas and Major cities (3.8 and 3.9 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively)

- was highest for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest level of disadvantage) and lowest for people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest level of disadvantage) (5.0 and 3.1 DALY per 1,000 population, respectively) (Figure 7) (AIHW 2021).

For more information, see Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden.

Figure 7: Burden of disease due to osteoarthritis for remoteness area and socioeconomic group by sex and year

This figure shows the rate of total burden of disease due to osteoarthritis was highest for females living in Inner regional areas in 2018.

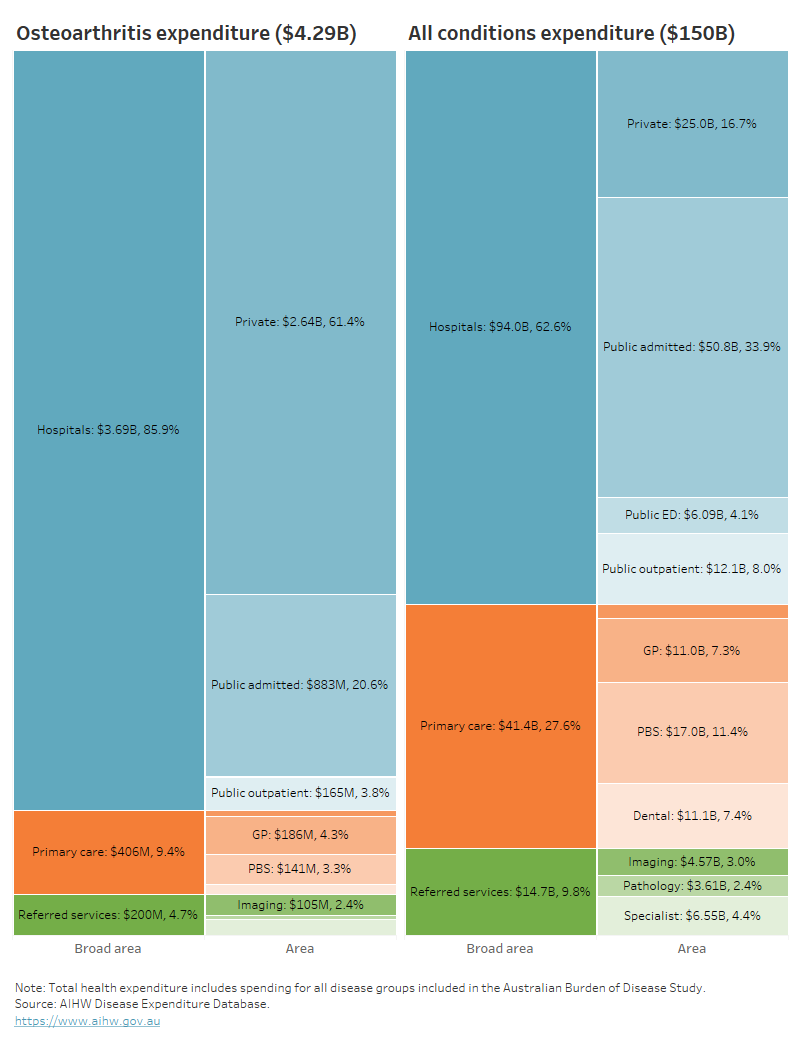

Health system expenditure

In 2020–21, an estimated $4.3 billion of expenditure in the Australian health system was for osteoarthritis, representing 2.9% of total health system expenditure and 29% of expenditure for all musculoskeletal conditions (AIHW 2023b).

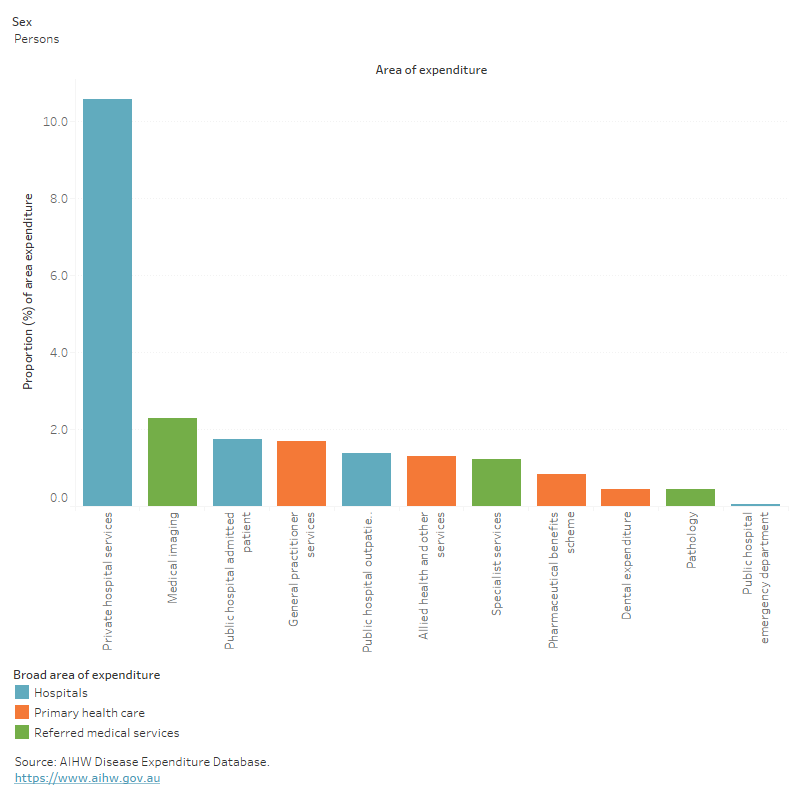

Where is the money spent?

In 2020–21, hospital services represented 86% ($3.7 billion) of osteoarthritis expenditure. This was more than the hospital proportion for all disease groups (63%). The private hospital services proportion of osteoarthritis expenditure was 3.7 times the proportion for all disease groups (61% and 17%, respectively).

Figure 8: Osteoarthritis expenditure attributed to each area of the health system, with comparison to all disease groups, 2020–21

This figure shows the public admitted patient hospital services proportion of osteoarthritis expenditure was $883 million in 2020-21.

In 2020–21, osteoarthritis accounted for:

- 11% ($2.6 billion) of all private hospital services expenditure – ranking 1st of all diseases/conditions

- 2.3% ($104.7 million) of all medical imaging expenditure (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Proportion of expenditure attributed to osteoarthritis, for each area of the health system, 2020–21

This figure shows that osteoarthritis accounted for 1.7% of all expenditure attributed to general practitioner services.

Who is the money spent on?

The distribution of health system expenditure on osteoarthritis by age and sex reflects the prevalence distribution, with more spending for older age groups and females.

In 2020–21:

- 97% of osteoarthritis expenditure was for people aged 45 and over

- 1.3 times more osteoarthritis expenditure was attributed to females compared with males ($2.4 billion and $1.9 billion, respectively), with a remaining $50.1 million (1.2%) unattributed to any sex.

For more information, see Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21.

In 2018–19, it was estimated that osteoarthritis expenditure per case was:

- 38% higher for males compared with females ($2,100 and $1,500 per case, respectively)

- 45% higher than musculoskeletal conditions as a group ($1,700 and $1,200 per case, respectively) (AIHW 2022b).

For more information, see Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors.

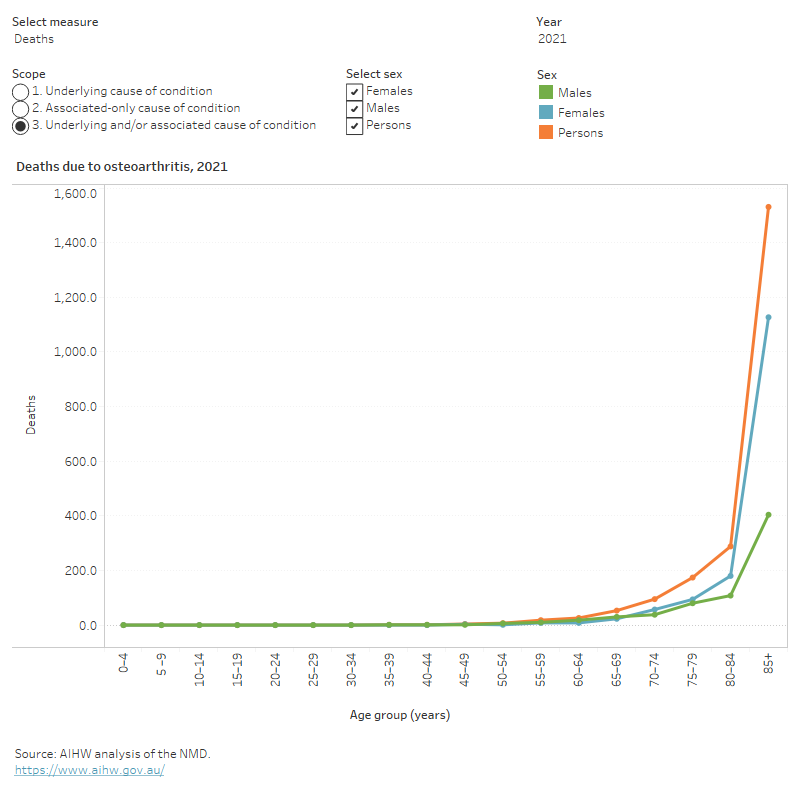

How many deaths were associated with osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis was recorded as an underlying and/or associated cause for 2,198 deaths or 6.0 deaths per 100,000 population in Australia in 2021, representing 1.3% of all deaths and 24% of all musculoskeletal deaths.

Osteoarthritis was the underlying cause for 105 deaths (4.8% of osteoarthritis deaths) and an associated cause only, for 2,093 deaths (95% osteoarthritis deaths).

Variation by age and sex

In 2021, osteoarthritis mortality (as the underlying and/or associated cause) in comparison to all deaths, was relatively concentrated among:

- older people (91% of osteoarthritis deaths were among people aged 75 and over, compared with 67% for total deaths)

- females (68% of osteoarthritis deaths were among females, compared with 48% of total deaths) (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Age distribution for osteoarthritis mortality, by sex, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that the osteoarthritis death rate was highest for people aged 85 and over (287 per 100,000 population) in 2021.

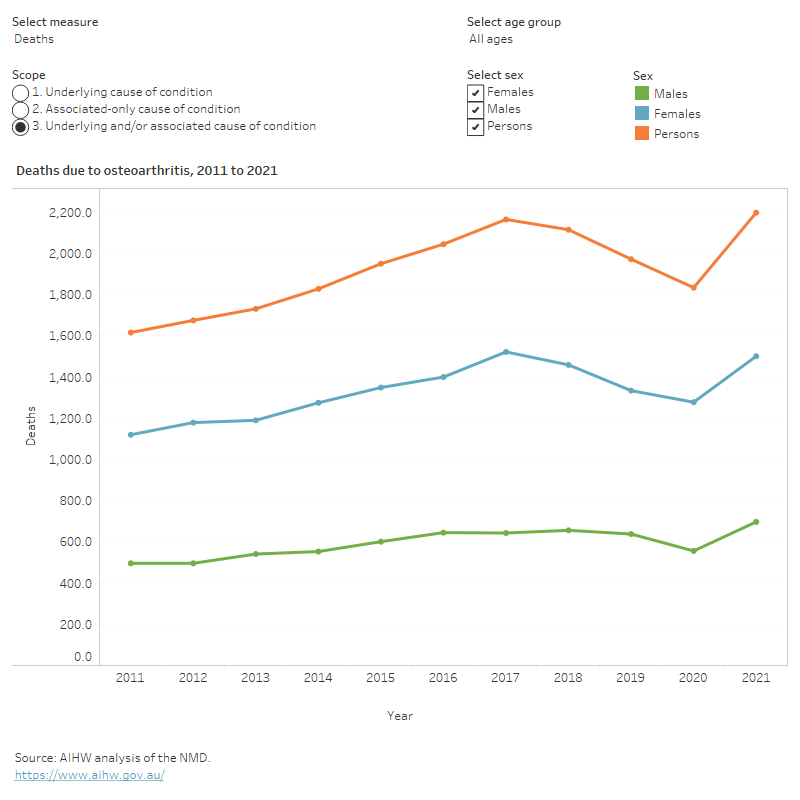

Trends over time

Age standardised mortality rates for osteoarthritis (as the underlying and/or associated cause) between 2011 and 2021:

- trended approximately flat, averaging 6.0 per 100,000 population over the period

- were 1.4 to 1.6 times as high for females compared with males (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Trends over time for osteoarthritis mortality, 2011 to 2021

This figure shows that death rates due to osteoarthritis remained stable between 2011 and 2021 (5.8 to 6.0 per 100,000 population), after adjusting for age.

Variation between population groups

In 2021, age standardised mortality rates for osteoarthritis (as the underlying and/or associated cause) were:

- 1.3 times as high for people living in Outer regional areas compared with people living in Major cities (7.7 and 5.8 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively)

- 1.4 times as high for people living in the lowest socioeconomic areas (with the highest levels of disadvantage) compared with people living in the highest socioeconomic areas (with the lowest levels of disadvantage) (6.7 and 4.9 deaths per 100,000 population, respectively).

For more information on mortality data, see the Chronic musculoskeletal condition mortality data tables 2023.

Treatment and management of osteoarthritis

At present there is no cure for osteoarthritis and the disease is long-term and progressive. Treatment for osteoarthritis aims to manage symptoms, increase mobility and maximise quality of life. Treatment options for osteoarthritis include:

- physical activity

- weight management

- medication

- joint replacement surgery.

General practitioners and osteoarthritis treatment

General practitioners (GPs) are usually the first point of contact with the health care system for people with osteoarthritis (McKenzie and Torkington 2010; RACGP 2018) and are ideally placed to play the role of care coordinator to ensure treatment continuity (RACGP 2018).

GP management of osteoarthritis may include assessment and diagnosis, referral to other health services, prescribing medication and providing education about the condition.

Until 2017, the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) survey was the most detailed source of data about general practice activity in Australia (Britt et al. 2016). Around 2.6 of every 100 encounters were for osteoarthritis in 2015–16 (Britt et al. 2016). This has changed little since 2006–07.

It is worth noting that there is currently no nationally consistent primary health care data collection to monitor provision of care by GPs. For more information, see General practice, allied health and other primary care services.

What medicines are used to treat osteoarthritis?

Treatment of osteoarthritis with medication aims to relieve pain, reduce inflammation and improve functioning and quality of life. Analgesics, or pain medications, are commonly used to manage the pain of osteoarthritis. Analgesics include paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioid analgesics.

For those with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis requiring pain relief, it may be reasonable to trial the use of paracetamol or NSAIDs for a short period and then discontinue use if it is not effective (RACGP 2018).

Corticosteroid injections may also be recommended for short term pain relief for hip and/or knee osteoarthritis if appropriate (RACGP 2018). Opioids are not recommended for the treatment of hip and/or knee osteoarthritis (RACGP 2018).

What other treatments are recommended for osteoarthritis?

Exercise is an important and effective component in both management and prevention of osteoarthritis. Exercise helps improve symptoms (especially pain and joint stiffness) and quality of life by:

- increasing range of motion (the ability to move joints through their full motion)

- strengthening muscles around affected joints

- assisting in weight control

- reducing the risk of other chronic diseases (for example, diabetes and cardiovascular disease).

Exercise is also beneficial for other comorbidities and overall health (RACGP 2018). A GP or Exercise Physiologist should be consulted before undertaking an exercise program.

Being overweight increases the risk of developing osteoarthritis, due to the increased load on weight bearing joints and increased stress on cartilage. Weight management is strongly recommended for people with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis who are overweight or obese (RACGP 2018).

For people with existing osteoarthritis and who are overweight or obese, weight loss can help reduce symptoms (RACGP 2018). Weight loss should be combined with exercise for the greatest benefits (RACGP 2018). A GP or Dietitian can be consulted to discuss weight loss/management strategies.

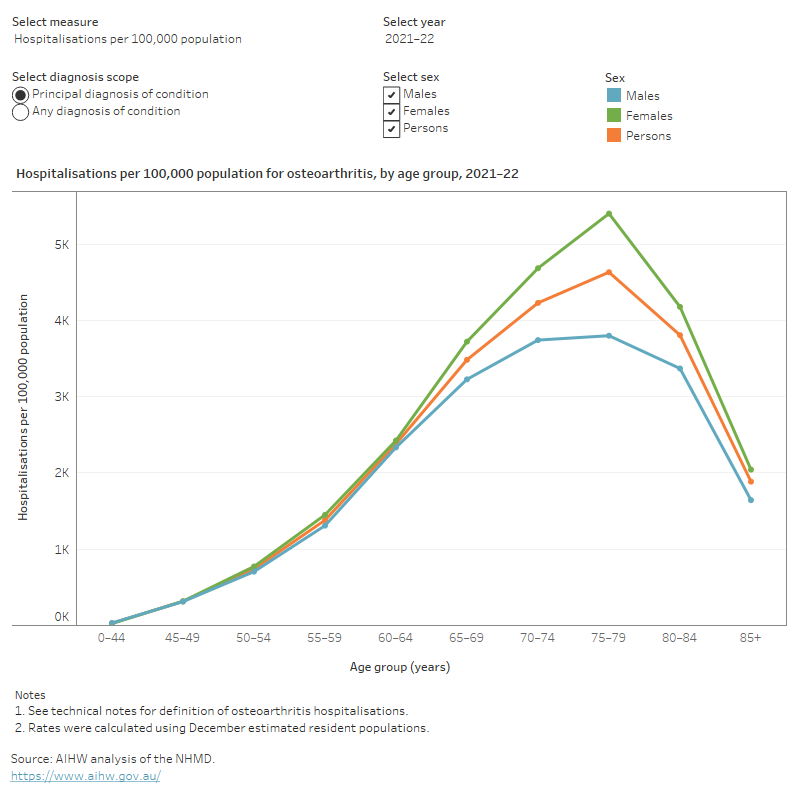

Hospitalisations for osteoarthritis

Data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) show that in 2021–22, there were 285,000 hospitalisations with a principal or additional diagnosis (any diagnosis) of osteoarthritis, representing 2.5% of all hospitalisations.

The rest of this section discusses hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoarthritis, unless otherwise stated. However, charts and tables also include statistics for any diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

In 2021–22:

- there were 242,000 hospitalisations, representing 2.1% of all hospitalisations in Australia, and 940 hospitalisations per 100,000 population

- osteoarthritis accounted for 786,000 bed days, representing 2.5% of all bed days

- 53% of osteoarthritis hospitalisations were overnight stays, with an average length of 5.2 days (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Age distribution for osteoarthritis hospitalisations, by sex, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows that the hospitalisation rate for osteoarthritis increased with age up to 75–79 group, decreasing thereafter.

Variation by age and sex

In 2021–22, osteoarthritis hospitalisation rates were:

- highest for people aged 75–79 years (4,600 per 100,000 population) (Figure 12)

- 1.3 times as high for females compared with males (1,000 and 830 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Figure 13).

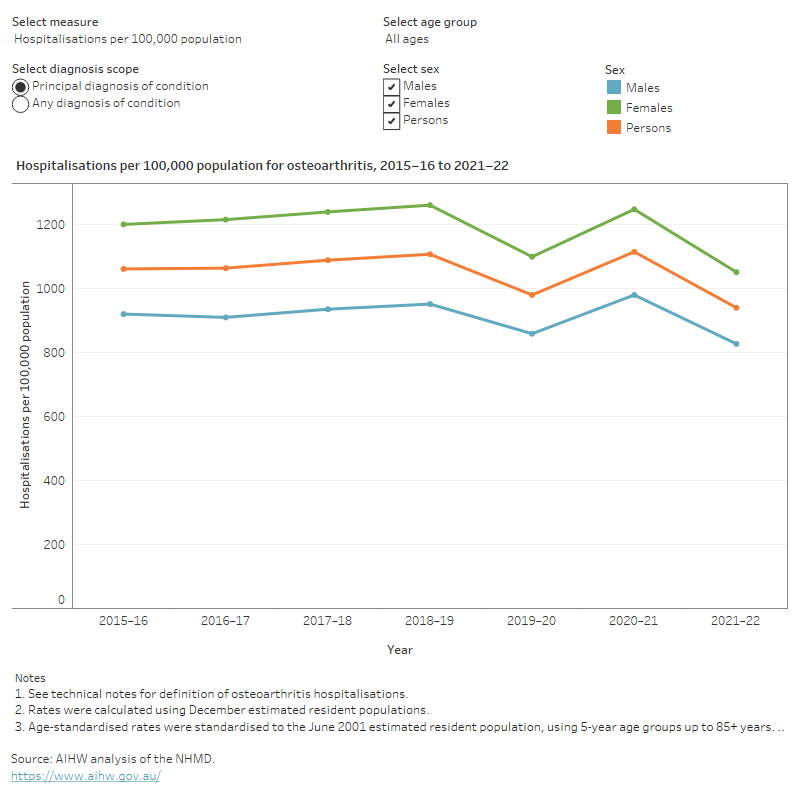

Trends over time

For osteoarthritis hospitalisations from 2015–16 to 2021–22:

- rates have fluctuated around an average of 1,000 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, within the range 940 to 1100 hospitalisations per 100,000, and with a notable increase in volatility over the last few years

- the proportion of overnight stays has fluctuated around an average of 51% within the range 49% to 53%

- the average length of overnight stays gradually decreased from 6.2 to 5.2 days (Figure 13).

It should be noted that the rate of hospitalisations over the past few years may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data prior to 2015–16 are not presented because rehabilitation hospitalisations were coded differently prior to this year.

Figure 13: Trends over time for osteoarthritis hospitalisations, 2015–16 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between 2015–16 and 2021–22, osteoarthritis hospitalisation rates were consistently higher among females compared with males.

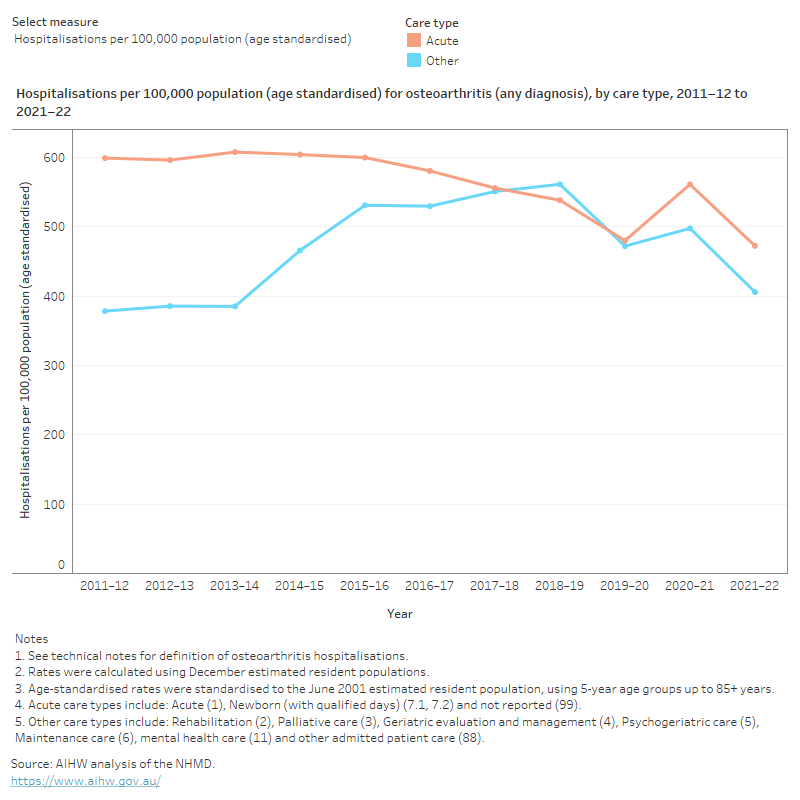

Between 2011–12 and 2021–22, for osteoarthritis:

- the acute care hospitalisation rate has averaged around 650, and ranged between 570 and 680 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, with increased volatility over the last few years, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic

- the hospitalisation rate for other care types (inclusive of sub-acute and non-acute care) increased to 2018–19 (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) and then decreased

- the average length of stay for acute care decreased from 4.5 to 4.0 bed days

- the average length of stay for non-acute care trended down from 4.6 days to 3.8 days (Figure 14).

Figure 14: Trends over time for osteoarthritis hospitalisations by care type, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that except for 2018–19 and 2019–20, osteoarthritis hospitalisations for acute care were higher compared with other care types.

In 2021–22, osteoarthritis was the most common reason for rehabilitation care with arthrosis of knee accounting for 22% and arthrosis of hip accounting for 9.4% of all rehabilitation hospitalisations (AIHW 2022c).

The primary purpose of rehabilitation care is to improve functioning of a patient with an impairment, activity limitation, or participation restriction due to a health condition.

Joint replacement surgery

Osteoarthritis is also the most common condition leading to hip and knee replacement surgery in Australia (AOANJRR 2019). Joint replacement is a cost-effective and clinically effective treatment for severe osteoarthritis (RACGP 2018).

Clinical guidelines in Australia recommend considering joint replacement surgery for severe osteoarthritis if all conservative treatment options have failed (RACGP 2018). These procedures restore joint function, help relieve pain and improve the quality of life of the affected person.

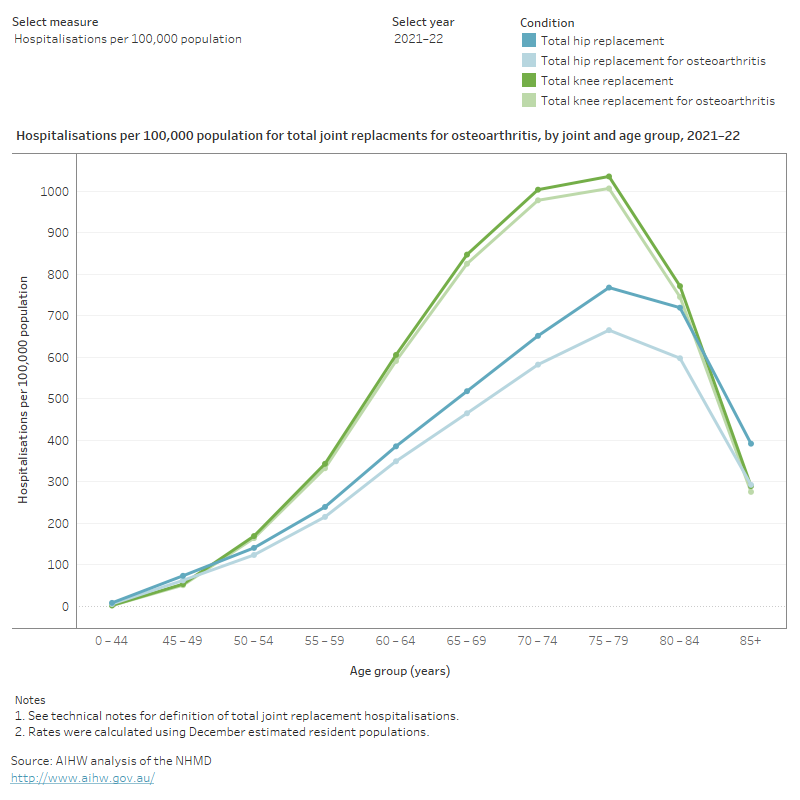

In 2021–22:

- 53,500 knee replacements and 35,500 hip replacements were performed in hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of osteoarthritis (210 and 140 per 100,000 population, respectively)

- the rate of knee or hip replacements increased steeply with age up to 75–79, and then declined with age up to 85 and over (Figure 15)

- the average length of stay for knee and hip replacements both increased with age from around 4 days for people aged 45–49 to around 6 days for people aged 85 and over.

Figure 15: Age profile of total knee and hip replacements

This figure shows that in 2021–22, hospitalisations for total knee replacements were consistently higher compared with total hip replacements for people aged 50–54 to 80–84.

Between 2011–12 and 2021–22 for hospitalisations where osteoarthritis was the principal diagnosis:

- crude rates of both hip and knee replacement surgeries increased slightly

- the age-standardised rate of total hip replacement surgeries increased slightly, while the age-standardised rate of total knee replacement surgeries remained stable

- age standardised and crude rates, for both hip and knee replacement surgeries fluctuated over the last few years, with lower rates during the pandemic when elective surgeries were cancelled. Rates then increased due to a backlog of surgeries. The rate in 2021–22 was higher than pre-pandemic, likely due to an increase in the ageing population (Figure 16).

Figure 16: Trends in total knee and hip replacements for osteoarthritis, 2011–12 to 2021–22

This figure shows that between 2011–12 and 2021–22, hospitalisation rates for knee replacements were consistently higher compared to hip replacements.

Comorbidities of osteoarthritis

People with osteoarthritis often have other chronic conditions, known as a comorbidity. For this analysis, the following comorbidities were considered:

- heart, stroke and vascular disease

- kidney disease

- arthritis

- mental and behavioural conditions

- asthma

- diabetes

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- osteoporosis or osteopenia

- cancer.

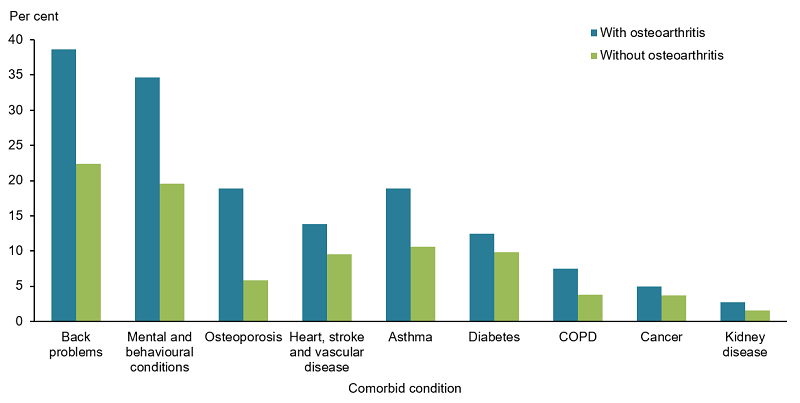

According to the NHS, in 2017–18, among people aged 45 and over with osteoarthritis:

- 38% also had back problems compared with 23% of people without osteoarthritis

- 31% also had mental and behavioural conditions compared with 20% of people without osteoarthritis

- 22% also had osteoporosis or osteopenia compared with 6% of people without osteoarthritis, equivalent to a prevalence ratio of 4.0 (or 3.2 after adjusting for age) which was the highest across the nine comorbidities.

Most chronic conditions are more common in older age groups. The average age of people with osteoarthritis is older than the average age of the general population, so people with osteoarthritis are more likely to have age-related comorbidities.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of people with and without osteoarthritis, the rates of the selected comorbidities were all higher for people with osteoarthritis compared with those without. With the exception of cancer, all of these differences were statistically significant (Figure 17).

It is important to note that regardless of the differences in age structures, having multiple chronic health problems is often associated with worse health outcomes (Parekh et al. 2011), in addition to a poorer quality of life (McDaid et al. 2013) and more complex clinical management and increased health costs.

Figure 17: Prevalence of other chronic conditions in people aged 45 and over with and without osteoarthritis, 2017–18

Notes:

- Age-standardised to the 2001 Australian population.

- Proportions do not total 100% as one person may have more than one additional diagnosis.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS 2019 (Osteoarthritis 2023 Supplementary data table 3.1).

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019) Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18, AIHW analysis of detailed microdata, accessed 28 April 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 22 May 2023.

AIHW (2022a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2022b) Health system spending per case of disease and for certain risk factors, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2022c) Admitted patient care 2020–21: Australian hospital statistics. Health services series no. 84, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

AIHW (2023a) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AIHW (2023b) Disease expenditure in Australia 2020–21, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 14 December 2023.

AOANJRR (Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry) (2019) Hip, Knee & Shoulder Arthroplasty 2019 Annual Report, AOA website, accessed 19 May 2023.

Briggs AM, Cross MJ, Hoy DG, Sànchez-Riera L, Blyth FM, Woolf and March L (2016) ‘Musculoskeletal Health Conditions Represent a Global Threat to Healthy Aging: A Report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health’, Gerontologist, 56: S243-S255.

Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Bayram C, Valenti L, Harrison C, Pan Y, Wong C, Charles J, Gordon J, Pollack AJ and Chambers T (2016) ‘A decade of Australian general practice activity 2006–07 to 2015–16’, General practice, series no. 41, Sydney University Press.

Chapman K and Valdes AM (2012) ‘Genetic factors in OA pathogenesis’, Bone, 51:64–72.

Cooper RD, Kuh D and Hardy R (2010) ‘Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis’, British Medical Journal, 341:c4467.

McDaid O, Hanly MJ, Richardson K, Kee F, Kenny RA and Savva GM (2013) ‘The effect of multiple chronic conditions on self-rated health, disability and quality of life among the older populations of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland: a comparison of two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys’, British Medical Journal Open, 3:e002571.

McKenzie S and Torkington A (2010) ‘Osteoarthritis: management options in general practice’, Australian Family Physician, 39 (9):622–625.

Parekh AK, Goodman RA, Gordon C and Koh HK (2011) ‘Managing multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework for improving health outcomes and quality of life’, Public Health Reports, 126:460–471.

RACGP (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) (2018) ‘Guideline for the management of knee and hip osteoarthritis’, 2nd edn, RACGP.

Sharma A, Kudesia P, Shi Q and Gandhi R (2016) ‘Anxiety and depression in patients with osteoarthritis: impact and management challenges’, Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews, 8:103–113.