Are housing outcomes for domestic and family violence clients improved over the long term?

Specialist homelessness services offer many options for those experiencing family and domestic violence that lack the resources or support to cope with a housing crisis. These clients present with a variety of housing circumstances: some clients are at imminent risk of losing their housing and others are already homeless when they seek support.

Between 2011-12 and 2013-14, housing outcomes for specialist homelessness services clients were recorded. A 'housing situation' is recorded at a client's first presentation to a specialist homelessness service agency, and then again at last presentation over this time period. Housing situations of clients may fluctuate, and a client may have multiple or even overlapping support periods, over the 3 year period. This analysis does not examine the variances in housing situations over the 3 years; rather, it looks at the housing situations of clients when first presenting to a specialist homelessness service in the 3 year period, and at the cessation of their last period of support. Housing outcomes can only be analysed when a period of support has ended; for this reason, only those clients who had ceased receiving support from an agency (that is, those with closed support periods) are included in this analysis.

Clients were assessed as being homeless or at risk of homelessness based on their dwelling type, tenure type and conditions of occupancy when first presenting to a homelessness agency and again when their support had ended. A client is considered homeless if they fall into one of three categories: no shelter or improvised dwelling, short term accommodation, and couch surfing or no tenure. A client is considered at risk of homelessness if they reside in public or community housing, private housing or institutional settings. The exact derivations are available in the glossary.

There are many factors which can increase a person's vulnerability to homelessness. A 2014 report Housing outcomes for groups vulnerable to homelessness: 1 July 2011 to 31 December 2013 by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) found that those who are more socially and economically disadvantaged had poorer housing outcomes. While domestic and family violence is a key driver of homelessness, not all are forced to leave their homes and there is considerable variation in life experiences and housing circumstances within this group.

Key findings

- At the end of the three years examined, following support, most clients experiencing domestic and family violence were living in stable accommodation (private rental/owning or social housing).

- Domestic and family violence clients groups with higher proportions of couch surfing or rough sleeping at the start of support, are less likely to be housed in private rental or social housing at the end of the three years examined.

- Adult male domestic and family violence clients were the most likely to be sleeping rough at the end of support (9%).

- Indigenous women experiencing domestic and family violence were the most likely to be living in social housing on last presentation (37%).

Which groups fare better or worse?

Specialist homelessness services were successful in reducing the proportion of clients considered homeless and increasing the proportion living in public or community housing at the end of support. This reflects the priority given to those experiencing domestic and family violence when it comes to a safe and stable housing outcome.

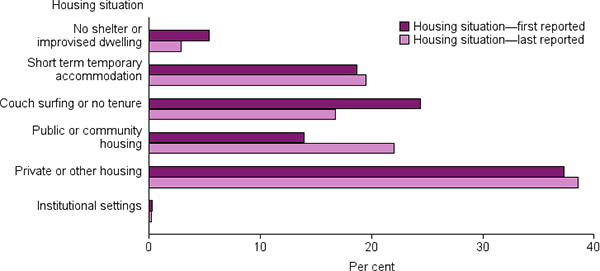

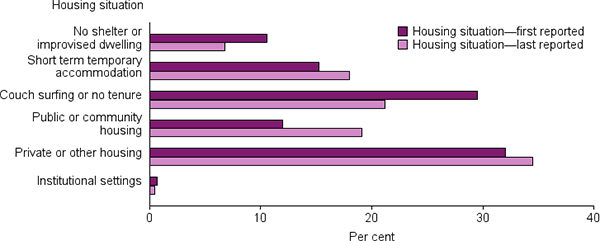

Over the three years to 2013-14, just under half (48%) of domestic and family violence clients were considered homeless ('no shelter or improvised dwelling', 'short term accommodation', and 'couch surfing or no tenure') on presentation (Figure 1). This is lower than the proportion for clients who have not experienced family and domestic violence over the 3 years examined, with over half of these clients considered homeless on presentation (55%) (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Domestic and family violence clients, by housing situation at beginning of support and at end of support, 2011-12 to 2013-14

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Data Repository.

The proportion of homeless ('no shelter or improvised dwelling', 'short term accommodation', and 'couch surfing or no tenure') clients was reduced by 9 percentage points in both groups to 39% for family and domestic violence clients and to 46% for non domestic and family violence clients at the end of the 3 years examined. The largest reductions for those experiencing domestic and family violence were in the proportion who reported that they were 'couch surfing or no tenure', falling from around 1 in 4 (24%) at the start of support to just 1 in 6 (17%) at the end.

Figure 2: Other clients, by housing situation at beginning of support and at end of support, 2011-12 to 2013-14

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Data Repository.

Homeless domestic and family violence clients

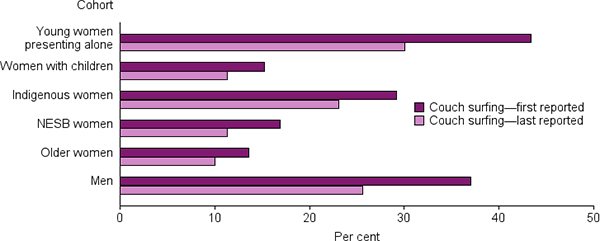

While family and domestic violence clients were less likely than other SHS clients to be homeless on presentation, there were 3 groups of clients within this cohort who were more likely than the overall group to be couch surfing or have no tenure when presenting to homelessness services.

These were:

- Young women presenting alone (43% at the start of support, falling to 30% at the end)

- Males (37% at the start of support, falling to 26% at the end) and

- Indigenous women (29% at the start of support, falling to 23% at the end).

Specialist homelessness services were successful in reducing the proportion of clients 'couch surfing or no tenure'. However, the groups above were still more likely to be living without tenure at the end of the 3 years examined than older women, women with children and women from non-English speaking backgrounds were prior to receiving support (only 14% of older women, 15% of women with children, and 17% of women from non-English speaking backgrounds presented with couch surfing or no tenure) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Domestic and family violence clients, by couch surfing or no tenure, by cohort at beginning of support and at end of support, 2011-12 to 2013-14

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Data Repository.

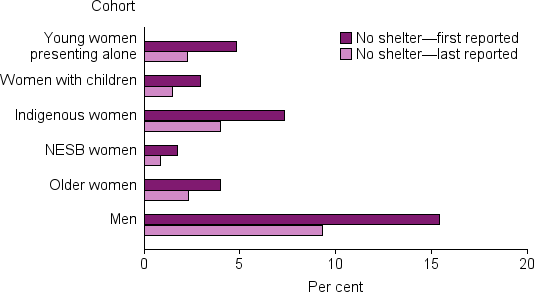

Those who are living in 'no shelter or improvised dwellings' or rough sleeping made up only a small proportion of the domestic and family violence clients, at around 5%. However, they are in the most unsafe and unstable circumstances. Certain client groups were more likely than the overall group to be in no shelter or improvised dwellings on presentation to a service.

These were:

- Males (15% at the start of support, falling to 9% at the end) and

- Indigenous women (7% at the start of support, falling to 4% at the end).

Proportions of clients living with no shelter or in an improvised dwelling reduced at the end of the 3 years examined, with the largest percentage point reduction experienced by men (6 percentage points) in the cohort. Indigenous women and young women presenting alone has the second highest reduction in proportions sleeping rough at 3%.

Clients with higher proportions of 'couch surfing or no tenure', such as young women presenting alone, or 'no shelter or improvised dwellings', such as men, at the start of support, were less likely to be housed in social or private housing at the end of support. At the cessation of their last period of support, only 48% of young women and 38% of men were housed in either private rental or social housing. This is compared with 74% of women with children, 78% of older women and 68% of women from non-English speaking backgrounds (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Domestic and family violence clients, by no shelter or improvised dwelling, by cohort at beginning of support and at end of support, 2011-12 to 2013-14

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Data Repository.

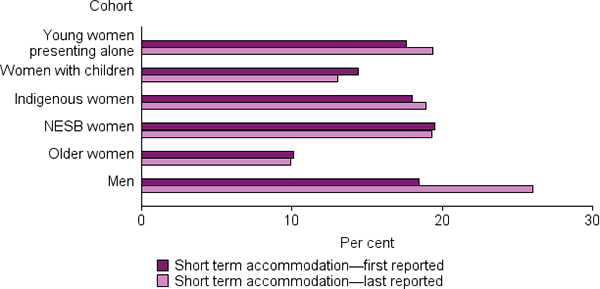

'Short term and temporary accommodation' rates generally remained steady among the domestic and family violence groups examined. However, the proportion of males ending support in short term or temporary accommodation rose from 18% to 26% (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Domestic and family violence clients, by short term temporary accommodation, by cohort at beginning of support and at end of support, 2011-12 to 2013-14

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Data Repository.

Domestic and family violence clients at risk of homelessness

Those experiencing domestic and family violence were more likely than those not to be living in social housing, private rental/owning on presentation (51% compared with 44% of non-domestic and family violence clients). This proportion increased by 10 percentage points to 61% at the end of the 3 years examined. This compares with 54% following support in the non-domestic and family violence cohort.

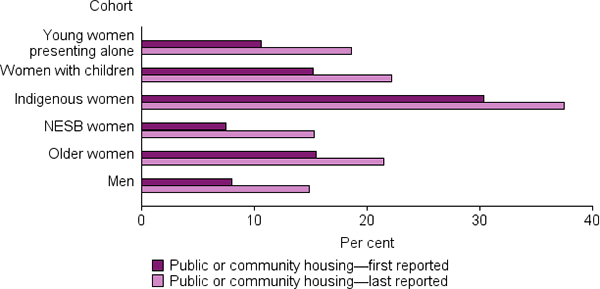

Homelessness agencies play a key role in liaising with both public and community housing providers to assist people into more stable housing situations. There was an overall increase of 8 percentage points, from 14% on first presentation to 22% at the end in those living in social housing, as well as a 2 percentage point increase to 39% in those living in private rental/owning properties at the end of support.

Indigenous women experiencing domestic and family violence were the most likely of all the groups to be living in social housing both before (30%) and after support (37%) and the least likely of all groups to be living in private rental/owning accommodation both before (15%) and after support (16%) (Figure 6). This is consistent with AIHW research released in 2014 which found that in 2013, Indigenous households were 6 times as likely as other Australian households to live in social housing (rates of 31% and 5%, respectively) [2].

Just over 1 in 5 (22%) women with children ended support in social housing, rising from 15% at the start of support. The proportion of non-English speaking women and young women presenting alone who ended support in social housing almost doubled, from 8% to 15% for non-English speaking women and from 11% to 19% for young women presenting alone. Males were also assisted in obtaining social housing with 15% at the end of support, up from 8% at the beginning.

Figure 6: Domestic and family violence clients, by public or community housing (renter or rent free), by cohort at beginning of support and at end of support, 2011-12 to 2013-14

Source: AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Data Repository.

The proportion of domestic and family violence clients living in private rental/owning accommodation remained steady from beginning to the end of support. Over half of older women (57%), women with children (52%) and non-English speaking women (54%) presented to services while living in the private rental market and these proportions remained consistent. This may indicate that homelessness services are successful in assisting women to remain in their homes following a violent incident. The NSW program Going Home, Leaving Violence is an example of a program which assists women to remain in their homes following a violent incident. These types of programs are being implemented across the country to challenge the assumption that when violence occurs, it is the women and children that must leave the home.

What does this tell us?

Across all groups examined in the domestic and family violence cohort, the proportion of clients moving in to public and community housing increased, representing a safe and sustainable housing outcome at the end of the 3 years examined. Domestic and family violence clients overall were also more likely than other SHS clients to be living in social housing following support (22% compared with 19%). This appears to reflect the high priority that those experiencing domestic and family violence and Indigenous families are given in the social housing systems nationally. Almost 4 in 10 Indigenous women experiencing domestic and family violence ended support in social housing: a safe, stable and sustainable outcome.

For groups with relatively high proportions of clients living with no tenure (males, Indigenous women and young women presenting alone) the reality of couch surfing or movement between friends' and relatives' houses is reflected. These people appear to be more likely to have exhausted all available options before presenting to a homelessness service. While this may be the case for the men studied, it could also be that they have been required to leave the family home following a violent incident. This analysis appears to indicate that males, young women and Indigenous women are at the greatest risk of falling into homelessness as they are more likely than other groups examined to be living without tenure upon presentation.

Older women and women with children experienced the smallest percentage point reduction in the proportion of no shelter or improvised dwellings. This could indicate that accommodation options for older women and those with children who were without shelter is harder to find, or that there is simply not enough availability of suitable accommodation for these groups.

Short term and temporary accommodation rates remained steady across all groups; however males experienced an 8 percentage point increase in the proportion housed temporarily from beginning to the end of support, from 18% to 26%. This could be a reflection of men being housed temporarily after being removed from their home following a violent incident.

Housing outcomes for those experiencing domestic and family violence over the 3 year period examined show that most clients end up either in private rental or social housing. Around 3 in 4 women with children, almost 8 in 10 older women, and almost 7 in 10 non-English speaking women are housed either in social housing or private rental.

However, for those with higher proportions of couch surfing or no tenure or no shelter or improvised dwellings at the start of support, being housed in private rental or social housing is much less likely at the end of the three years examined. Young women presenting alone had the highest proportion of couch surfing or no tenure on first presentation (43%), and males were the most likely to be sleeping rough (15%). At the end of the 3 years examined, less than half of young women and males were housed in either private rental or social housing (48% and 38%, respectively). These 2 groups also have amongst the highest average number of support periods over the 3 years, with young women presenting alone receiving 3 support periods and males receiving 3.3 support periods (see the 'What are the patterns of service use among domestic and family violence clients?' snapshot for further information). This appears to indicate greater levels of housing instability, requiring specialist homelessness service intervention and assistance. This instability over the long term appears to result in these groups being the least likely to obtain a private rental or social housing tenancy.

If you are experiencing domestic or family violence or know someone who is, please call 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732) or visit the 1800RESPECT website.

References

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2015. Exploring transitions between homelessness and public housing: 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2013. Cat. no. HOU 277. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014. Housing assistance for Indigenous Australians. Cat. no. IHW 131. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 24 September 2015.