Government sources

Australian Government spending

In 2019–20, Australian Government spending was $86.4 billion, representing a $4.6 billion real increase (5.6%) from 2018–19 (Table 10). This was higher than the average real growth in the decade to 2019–20 (3.2%).

The growth of Australian Government spending between 2018–19 and 2019–20 was due partly to an increase in grants to states and territories (10.8%) (Table 12).

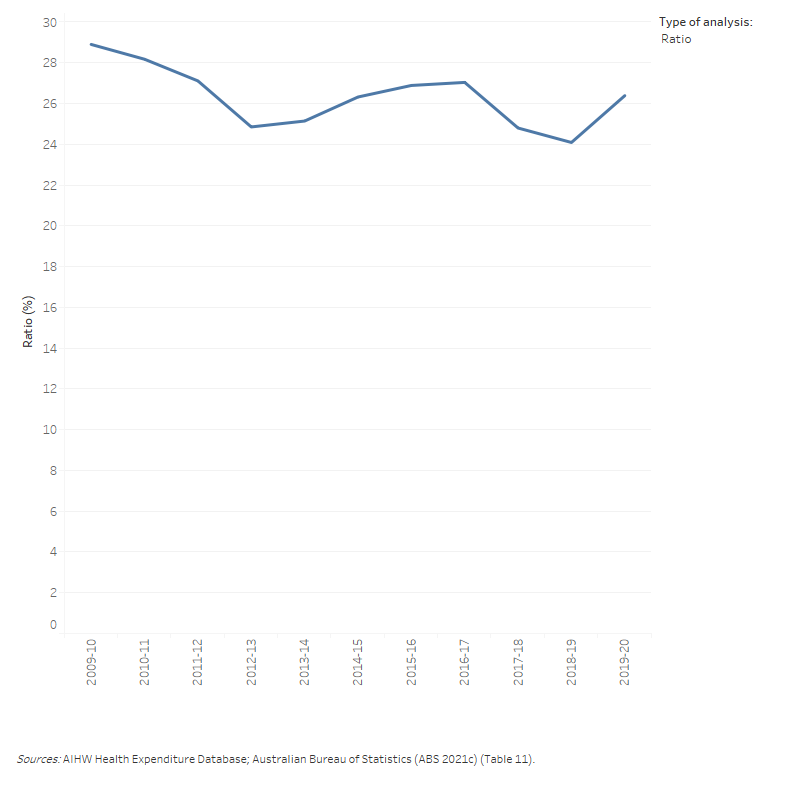

The $86.4 billion of health spending in 2019–20 by the Australian Government represented 26.4% of tax revenue, 2.3% higher than in 2018–19 (Figure 9). This is due to the fact that Australian Government nominal health spending grew by 7.3% while its tax revenue decreased by 2.0% in 2019–20 (Table 11).

Figure 9: Ratio of Australian Government health spending to Australian Government tax revenue, current prices, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows the dollar amounts of the Australian Government tax revenue and health spending with an additional line showing the ratio of the Australian Government health spending to tax revenue as a percentage. Australian government health spending increased from $53.1 billion in 2009–10 to $86.4 billion in 2019–20. Australian Government tax revenue was higher than health spending for all years. Tax revenue increased from $183.7 billion in 2009–10 to $327.5 billion in 2019–20. The highest ratio of 28.9 per cent was in 2009–10 and the lowest one was 24.1 per cent in 2018–19.

Australian Government spending in 2019–20 (Figure 10) comprised:

- direct Australian Government spending ($50.7 billion, or 58.7%), mostly administered through the Department of Health on programs for which the government has responsibility, such as the MBS, PBS and health research. For the first time, this also includes some health spending by the Department of Defence ($524 million)

- grants to states and territories ($26.8 billion, or 31.0%), including National Health Reform funding, National Partnership on COVID-19 Response (NPCR), other National Partnership Payments (NPPs) and the Highly specialised drug (HSD) funding in public hospitals

- rebates and subsidies for privately insured people under the national Private Health Insurance Act 2007 ($6.1 billion, or 7.0%)

- DVA funding for goods and services provided to eligible veterans and their dependants ($2.9 billion, or 3.3%)

- medical expenses tax rebate ($4 million, officially phased out after 2018–19).

The 5.6% increase in Australian Government spending between 2018–19 and 2019–20 can be attributed to increases to specific program spending ($2.1 billion increase) and funding to states and territories through grants ($2.6 billion increase). The main driver of this increase was the funding by the Australian Government from March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

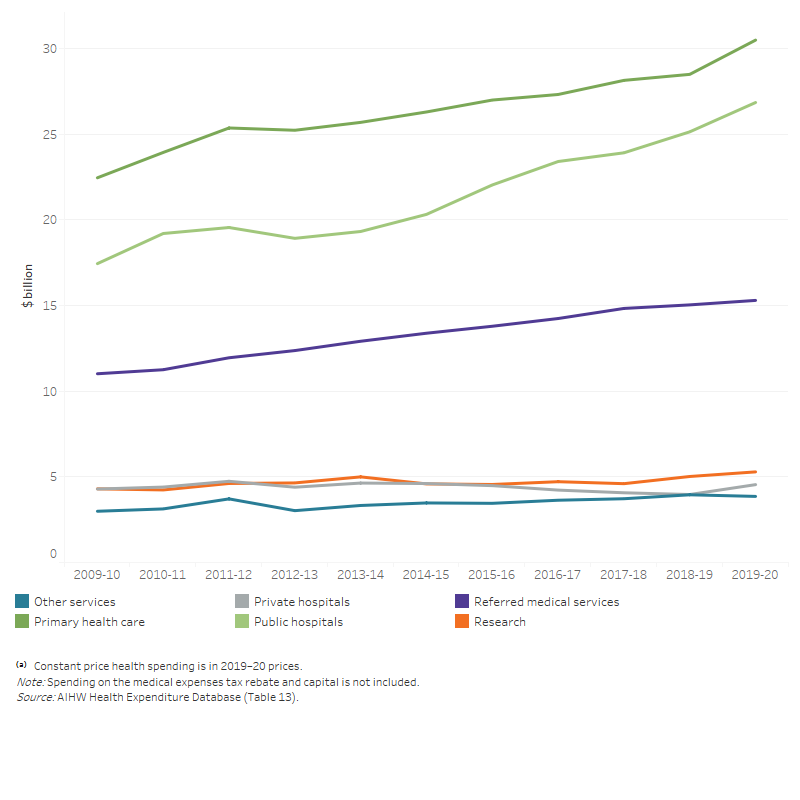

Figure 10: Australian Government total health spending by program, constant prices⁽ᵃ⁾, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that from 2009–10 to 2019–20 the Australian Government spent the most to least on own program spending, grants to states, health insurance premium rebates and Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Over the 10-year period, there was an overall increase in health spending by the Australian Government for each program excluding on Department of Veterans’ Affairs. In 2019–20, The Australian Government spent $50.7 billion on own program spending, $26.8 billion on grants to states, $6.0 billion on health insurance premium rebates and $2.9 billion on Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

COVID-19 related health spending funded by the Australian Government in 2019–20

The COVID-19 pandemic and related responses had a significant impact on all aspects of the health system. Only some of this is directly attributable to funding for programs specifically targeted to the COVID-19 response, including:

- National Health Reform funding to states and territories

Australian Government spending in 2019–20 in the NPCR comprised (a) public hospitals ($1.4 billion), (b) private hospitals ($0.5 billion), (c) patient transport services ($0.06 billion), (d) community health ($0.1 billion), public health ($0.2 billion) and (e) capital expenditure ($0.2 billion).

- Direct Australian Government spending

In 2019–20, Australian Government health spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was estimated to be $1.7 billion. Of this: (a) unreferred medical services through MBS telehealth contributed $1.1 billion (b) public health mainly related to primary care respiratory clinics and distributions of PPE was $0.3 billion, (c) referred medical services through MBS COVID-19 testing (MBS Microbiology Tests) was $0.09 billion and (d) administration mainly related to National Communication campaign was $0.07 billion.

Note that COVID-19 related spending for residential aged care is outside the scope of this report. This also does not include COVID-19 related spending by other Australian Government agencies, which might fall into a broader scheme of economic response to COVID-19.

During 2019–20, more than one-third (35.3%) of Australian Government health spending was for primary health care ($30.5 billion) (Figure 11). Of this:

- pharmaceuticals subsidised through the PBS contributed $11.4 billion

- unreferred medical services (mainly visits to a general practitioner) was $11.3 billion

- spending on other health practitioners was $2.5 billion (Table A6).

Figure 11: Australian Government health spending, by area of spending, constant prices⁽ᵃ⁾, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that from 2009–10 to 2019–20 Australian Government health spending increased in public hospitals, private hospitals, primary health care, referred medical services and research. In 2019–20, health spending was $30.5 billion on primary health care, $26.8 billion on public hospitals, $15.3 billion on referred medical services, $4.5 billion on private hospitals, and $5.3 billion on research. In the same year, spending on other services and capital decreased to $3.9 billion and $115 million, respectively.

Spending on public hospitals was the next largest area of Australian Government health spending (between $26.8 billion and $29.0 billion depending on how some MBS and PBS benefits for services provided in public hospitals are treated), followed by referred medical services ($15.3 billion or $13.7 billion also depending on how some MBS spending is treated).

The estimated spending on public hospitals and referred medical services by the Australian Government is represented as a range here to reflect additional components of MBS and PBS spending that have not historically been treated as public hospital spending in the national health accounts methodology but that are believed to be related to services provided in public hospitals.

MBS and PBS Section 100 funding by the Australian Government in public and private hospitals

The lower bound of $26.8 billion of the Australian Government spending on public hospital services includes spending by the Department of Veteran's Affairs (DVA), National Health Reform funding, Highly Specialised Drugs delivered through hospitals, a small grouping of other National Partnership Payments, an allocation of the private health insurance premium rebates, some specific programs administered by the Australian Government Departments of Health and Defence and capital consumption allocated to public hospitals. More details can be found in Table A11.

This amount currently does not include:

(i) Government benefits paid for in-hospital MBS, mostly for private patients in public and private hospitals. This includes both inpatients and outpatients (at public hospitals’ outpatient clinics). The majority of these components are currently allocated to Referred medical services. This is primarily because limitations in the MBS data mean public hospital spending cannot be directly derived, including:

(i.1) Only MBS payments for medical services provided to admitted patients are flagged as ‘in hospital’. Outpatient and non-medical services are not recorded as hospital services.

(i.2) MBS ‘in-hospital’ services cannot be differentiated by services provided to private patients in a private hospital versus services provided to private patients in a public hospital.

(i.3) In addition, MBS payments are generally made to individual patients and individual practitioners, rather than directly to hospitals. There are, however, arrangements in place, particularly between practitioners and hospitals, that can mean that part or all of the MBS benefits are passed on to the hospital in lieu of payments from patients or fees for private practice arrangements for practitioners in public hospitals. A lack of detail regarding exactly who ultimately receives the MBS benefits and these payments are treated in data provided by both the Australian Government and the states and territories has meant that there is currently no consensus as to how best to treat this revenue in the ANHA.

(ii) Except for the HSDs, some other PBS Section 100 programs (mainly the PBS Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy program, but also Chemotherapy Pharmaceutical Access Program (CPAP) and the Special Authority Program (trastuzumab - Herceptin), Botulinum Toxin Program, and Human Growth Hormone program) have a public hospital component that are allocated to the benefit-paid pharmaceuticals category. Many of the issues surrounding the MBS components also relate to these PBS components, including the difficulties surrounding the treatment of the revenue received.

While these limitations currently prevent the full incorporation of these MBS and PBS components into the area of public and private hospital spending, the AIHW has worked and will continue to work with the HEAC to develop a method for quantifying the amount of spending involved for both the MBS and PBS components and to better understand the likely flow-on impact for other spending categories such as referred medical services and benefit-paid pharmaceuticals.

The estimated quantities of these components is provided below for both public and private hospitals. This does not include an estimate of the non-medical components for the MBS for private hospitals as there is no data currently available to quantify this.

In terms of the flow-on impacts, the full inclusion of this new way of categorising this spending into the ANHA would result in reductions to the estimates for both referred medical services as well as pharmaceuticals (as spending is reallocated to hospitals) in addition to increasing the Australian Government contributions for both public and private hospitals.

The full inclusion would also be likely to result in reductions to public hospital spending estimates for Individuals and potentially States and territories, however the full effects require further works with HEAC to determine. The greatest impact is likely to be on the estimates for spending by Individuals on public hospital services, however, it is difficult to be certain of this given limitations in the available data.

Private hospitals spending would not be associated with the same degree of flow-on issues because the current estimation methods already exclude these amounts.

Estimates of Australian Government’s spending in public and private hospitals, including in-hospital MBS and PBS, 2019–20 ($ million)

|

Current figure |

MBS for admitted patients |

|

MBS for non-admitted patients |

PBS section 100 |

|

Total estimates |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public hospitals |

26,841 |

813 |

765 |

558 |

28,977 |

||

|

Private hospitals |

4,543 |

2,199 |

|

|

485 |

|

7,227 |

|

Total hospitals |

31,384 |

3,012 |

|

765 |

1,043 |

|

36,204 |

The AIHW is continuing to work with data providers to resolve outstanding issues and fully incorporate these new estimates into the ANHA.

Using the current estimates, the rise in total Australian Government spending between 2018–19 and 2019–20 was mostly due to an increase of $2.0 billion on primary health care, $1.7 billion on public hospitals, $0.6 billion on private hospitals, and $0.3 billion on research (Figure 11).

Over the decade since 2009–10, public hospitals ($9.4 billion) and primary health care ($8.0 billion) had the largest real increases in funding from the Australian Government. In real terms, these areas had an average yearly increase of 4.4% and 3.1% respectively (Figure 11). Note that growth calculations for Australian Government public hospital funding do not include additional components of MBS and PBS spending as stated above.

In 2019–20, private hospitals received an estimated real increase of $0.26 billion compared with 2009–10, an annual average increase of 0.6% (Figure 11).

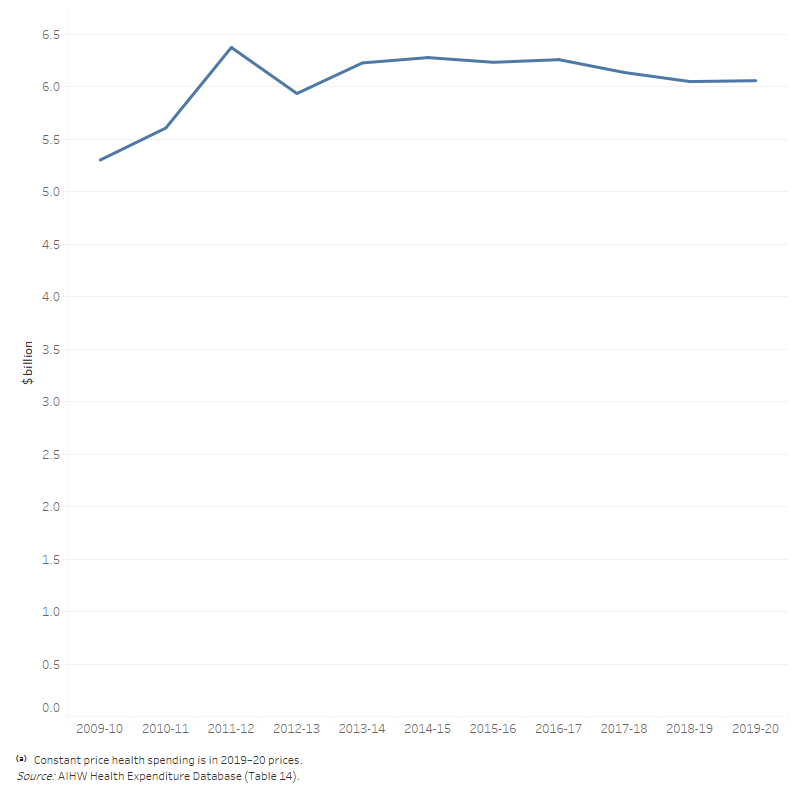

In 2019–20, the rebate for private health insurance premiums paid by the Australian Government was similar to that in 2018–19—$6.1 billion compared with $6 billion (Figure 12). The rebate amount presented here is an estimate of the rebate paid out as benefits (to estimate health spending). This is done to exclude spending on non-health related items such as health insurance advertising. It is therefore smaller than the total rebate paid to individuals to reduce premiums, which are reported elsewhere (such as in Department of Health and ATO annual reports). More details on the estimation can be found in the Australian National Health Account: concepts, methodology and data sources.

Figure 12: Health insurance premium rebates, constant prices⁽ᵃ⁾, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that health insurance premium rebates increased overall from 2009–10 to 2019–20. Health insurance premium rebates was highest in 2011–12 ($6.4 billion) and lowest in 2009–10 ($5.3 billion).

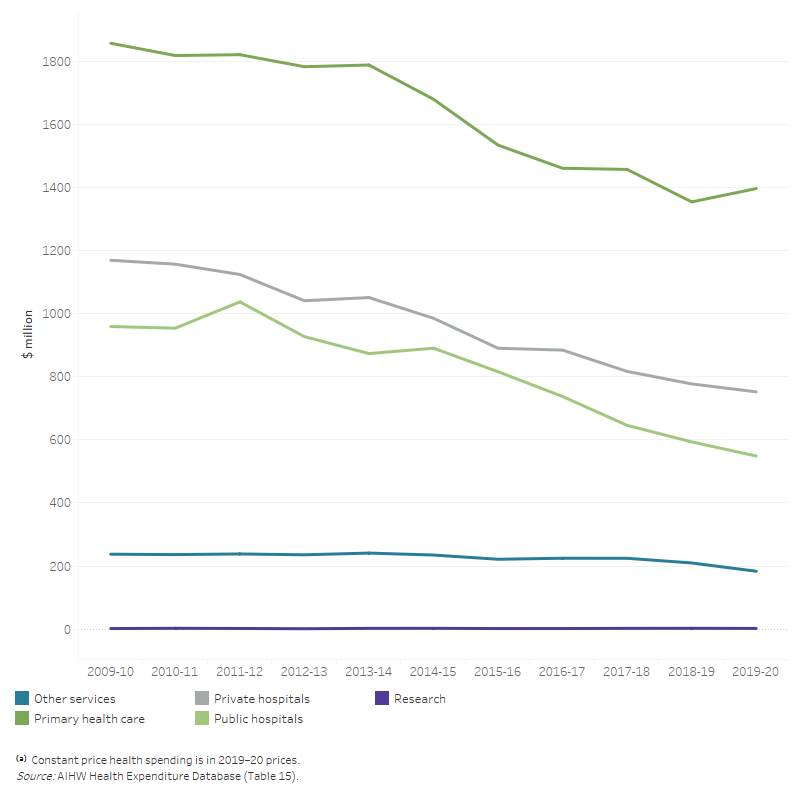

In 2019–20, the DVA spent $2.9 billion on health, mostly on primary health care ($1.4 billion) and hospitals ($1.3 billion). Total DVA spending decreased by 1.8% in 2019–20 (Figure 13a).

Over the decade to 2019–20, there was a consistent decline in DVA spending on hospitals, with public hospitals decreasing by an average of 5.4% per year and private hospitals by 4.3% in real terms. DVA spending on primary health care also decreased in real terms by a yearly average of 2.8%, accompanied by an average decrease in spending on other services by 2.6%.

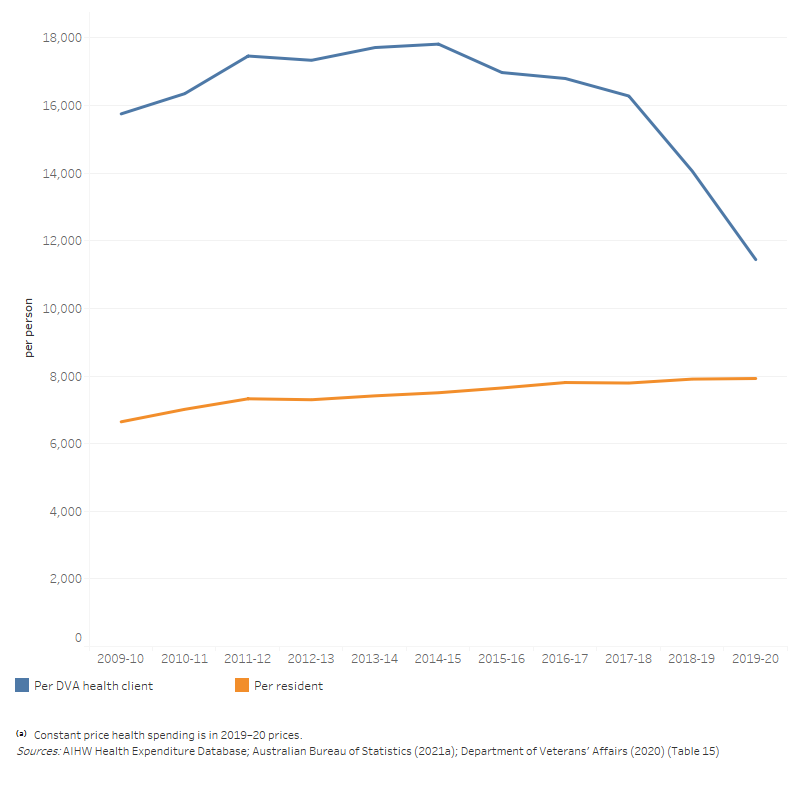

Based on the number of people in the DVA treatment population (which includes all DVA Orange, Gold and White cardholders), DVA spent $11,444 on health per member of the treatment population in 2019–20 which is 44.4% higher than the health spending per person in the total Australian population ($7,926). This average health spending per member of the DVA treatment population peaked in 2014–15 and decreased over the period 2015–16 to 2019–20 (Figure 13b). This recent downward trend in the health spending per member of the DVA treatment population is due to an increase in the number of DVA clients, including clients receiving a White card under Non-liability health care arrangements where treatment for mental health conditions are funded by DVA without accepting these conditions are service-related.

Figure 13a: Department of Veterans’ Affairs health spending by area of spending, constant prices⁽ᵃ⁾, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that Department of Veterans’ Affairs spent the most on primary health care and least on research. In 2019–20, spending on public hospitals, private hospitals and private health care decreased to $549 million, $752 million and $1,397 million respectively. Meanwhile, spending on other services and research remained relatively flat at around $226 million and $2 million, respectively, during the 10-year period.

Figure 13b: Average health spending per client of the DVA treatment population and per person in the Australian resident population, constant prices⁽ᵃ⁾, 2009–10 to 2019–20 ($)

Average health spending per client of DVA treatment population increased from $15,754 in 2009–10 to $17,817 in 2014–15, and then decreased to $11,444 in 2019–20. Health spending per member of DVA treatment population is often higher than the health spending per person in the total Australian population during the 10-year period.

In 2019–20, for the first time the Department of Defence (Joint Health Command) submitted some data on health spending, with a total of $524 million. The biggest area of spending was other health practitioners ($141 million), followed by referred medical services ($96 million), unreferred medical services ($84 million), private hospitals ($72 million), administration ($61 million), and dental services ($45 million). Trend analysis will be provided when more data are available in future reports.

The amounts shown represent actual health expenditure by the Department of Defence for its ADF and APS employees that could be categorised as per AIHW’s area of expenditure classification, including direct spending on health care to members, direct costs of pharmaceuticals purchased by the Department and costs for administration, including the Defence electronic health record.

It will not be possible to reconcile this exactly against other departmental financial reporting because some expenditure within the Joint Health Command is not related to patient care and because of the accounting practices (e.g. cost accrual) employed in departmental reporting. There are also areas of health expenditure within the Department that cannot be extracted from Departmental reporting such as building maintenance and other infrastructure costs and material used within the operational environment.

State and territory government spending

In 2019–20, state and territory governments spent $56.2 billion on health. In real terms, this was a 4.0% growth in spending from 2018–19 – an additional $2.2 billion (Table 10). This real growth was higher than the average growth rate over the period from 2009–10 to 2019–20 (3.5% per annum). This increase was likely caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

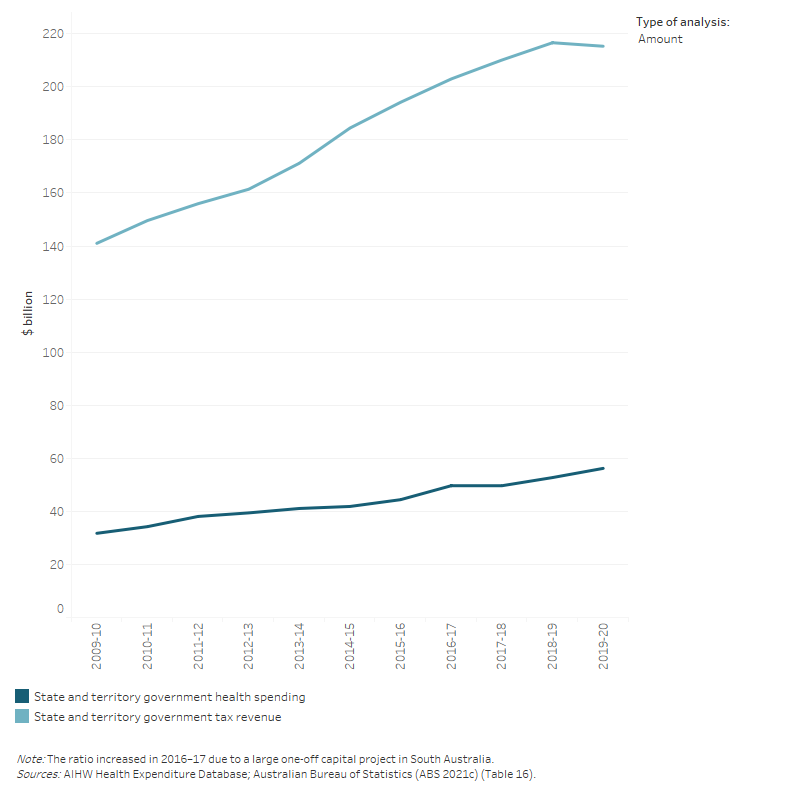

During 2019–20, health spending by state and territory governments was 26.1% of their tax revenue (Figure 14). This was 1.8 percentage points higher than 2018–19. This is due to the fact that State and territory governments’ nominal health spending increased by 6.6%, while tax revenue reduced by 0.6% (Table 16).

Figure 14: Ratio of state and territory government health spending to state and territory government tax revenue, current prices, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows the dollar amounts of the state and territory government tax revenue and health spending with an additional line showing the ratio of the state and territory government health spending to tax revenue as a percentage. State and territory government health spending increased from $31.7 billion in 2009–10 to $56.2 billion in 2019–20. State and territory tax revenue was higher than health spending for all years. Tax revenue increased from $141.0 billion in 2009–10 to $215.3 billion in 2019–20. Ratio of state and territory health spending to state and territory tax revenue increased over the 10-year period from 22.5 per cent to 26.1 per cent. The highest ratio of 26.1 per cent was in 2019–20.

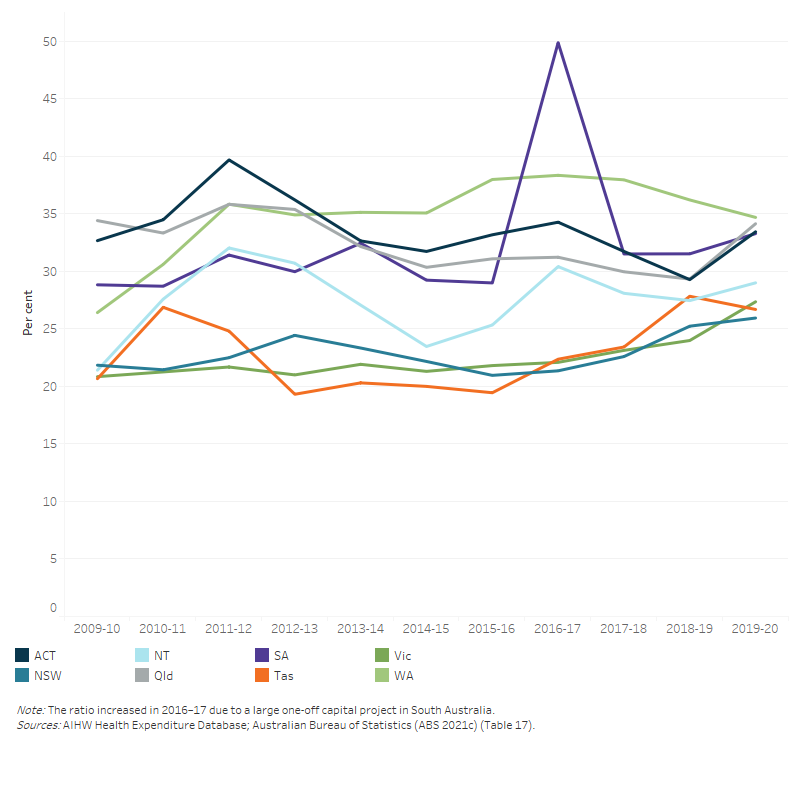

In 2019–20, the ratio of health spending to tax revenue varied across state and territory, with the highest in Western Australia (34.7%) and the lowest in New South Wales (25.9%) (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Ratio of total health spending to tax revenue for each state and territory government, current prices, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that ratio of health spending to tax revenue for all states and territories from 2009–10 to 2019–20. Over the 10-year period, the list of average ratio from highest to lowest is Western Australia (34.8 per cent), the Australian Capital Territory (33.6 per cent), Queensland (32.5 per cent), South Australia (32.3 per cent), the Northern Territory (27.5 per cent), New South Wales (22.9 per cent), Tasmania (22.9 per cent) and Victoria (22.4 per cent). The ratio increased significantly in 2016–17 for South Australia due to a large one-off capital spending project.

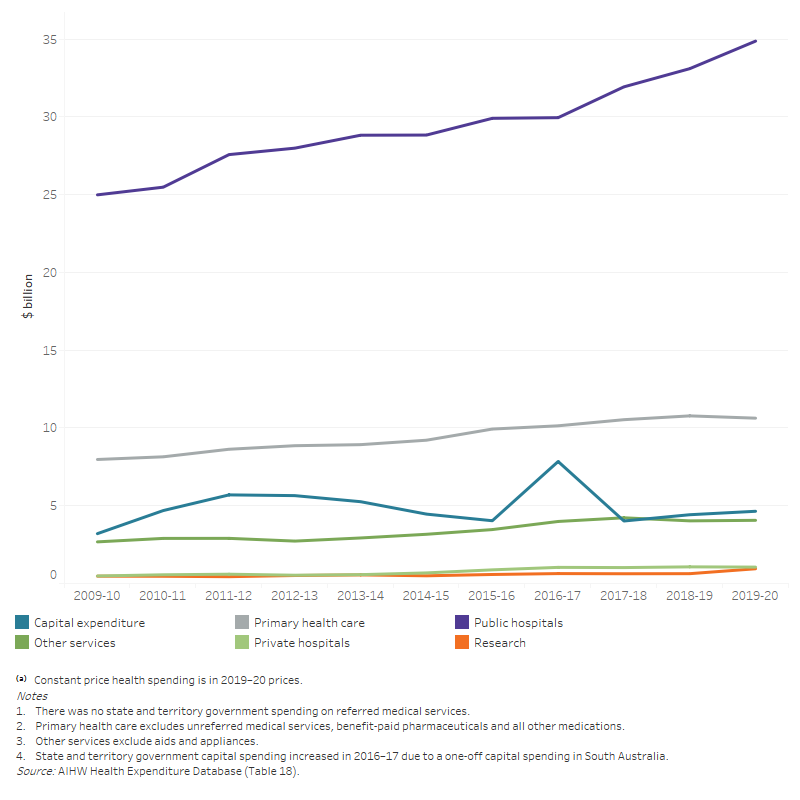

In 2019–20, state and territory governments spent $35.9 billion (63.9%) on hospitals, with the most ($34.9 billion) on public hospitals. Another $10.6 billion (18.9%) was spent on primary health care; $8.3 billion of which was in community health services (Figure 16; Table A6).

In 2019–20, state and territory spending increased in real terms in these areas:

- public hospital services by $1.8 billion (5.4% increase compared with 2018–19)

- research by $0.3 billion (50%)

- capital by $0.2 billion (5.0%)

- other services (patient transport services, aids and appliances, administration) by $0.03 billion (0.8%).

Spending on primary health care and private hospitals decreased by $0.1 billion (–1.4%) and $0.02 billion (–1.6%) respective

Figure 16: State and territory government total health spending, by area of spending, constant prices⁽ᵃ⁾, 2009–10 to 2019–20

The line graph shows that state and territory government health spending increased from 2009–10 to 2019–20 in all areas of spending. For the overall 10-year period, the largest increase was for public hospitals ($25 billion in 2009–10 to $34.9 billion in 2019–20). State and territory government health spending was relatively flatter for private hospitals, primary health service, other services and research. Capital spending by state and territory government increased in 2016–17 due to a large one-off capital spending project in South Australia.

These estimates of public hospital spending differ from those reported in the NHFB statistics for a range of reasons, including where funding is provided to support public hospital service delivery outside the NHFP, differences between cash and accrual accounting practices and treatments of capital and interests. More details can be found in Comparison and alignment of Australian health expenditure estimates.