Children on care and protection orders

Key findings: Children on a care and protection order, 2021–22

Care and protection orders (CPOs) are legal orders or arrangements that place partial or all responsibility for a child’s welfare with child protection agencies. In Australia, state and territory governments are responsible for statutory child protection. Their respective departments work with children and families to protect them from abuse, neglect or other harm (AIHW 2022).

Between 2016–17 to 2020–21, the rate of children on care and protection orders increased – from 9.9 per 1,000 children at 30 June 2017 to 10.9 per 1,000 children at 30 June 2021 (AIHW 2022). Of the 61,700 children on care and protection orders at 30 June 2021, most were living in home-based care (67%), with relatives/kinship care (39%) and foster care (27%) being the most common living arrangements.

Some children are placed in out-of-home care while others remain living at home with support from informal support networks, child protection agencies and community-based agencies.

Pathways into homelessness for children on care and protection orders are complex. For example, children who present alone may have absconded from their home due to family violence, abuse or neglect (Noble-Carr & Trew 2018). Children may also seek support from SHS agencies with their carers.

Family and domestic violence is one of the main reasons that families at risk of homelessness seek assistance from SHS agencies. It is also one of the leading reasons for statutory intervention, and SHS agencies often work with the same families as children as child protection authorities (MICAH Projects 2016).

Linked data has been used to describe the characteristics of children and young people who received both child protection (an investigated notification, care and protection order or out-of-home care) and specialist homelessness services (SHS) (AIHW 2016). Compared with children who accessed only SHS, children who accessed both child protection and SHS were more likely to have experienced family and domestic violence (53%, compared with 44%). For more information about children on care and protection orders, see Child protection Australia 2020–21.

Reporting children on care and protection orders in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

A client is considered to be under a care and protection order (CPO) if they are under 18 and have provided any of the following information in any support period during the reporting period.

They reported that they were under a CPO and had the following care arrangements:

- family group home

- residential care

- kinship care (reimbursed)

- kinship care (not reimbursed)

- foster care

- other home-based care (reimbursed)

- independent living

- other living arrangements

- parents, or

They have reported ‘transition from foster care/child safety residential placements’ as a reason for seeking assistance or the main reason for seeking assistance.

For more information, see Technical notes.

Client characteristics

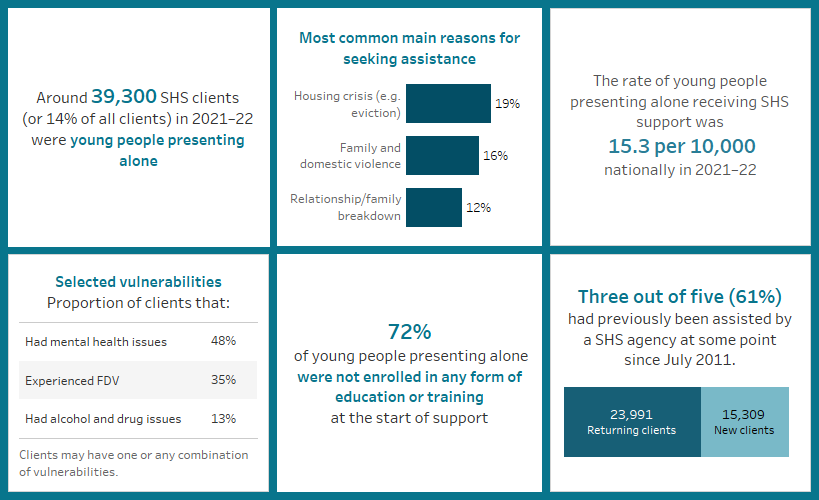

Figure CPO.1: Characteristics of children on care and protection orders

This interactive image describes the characteristics of around 7,900 children on a care and protection order who received SHS support in 2021–22. Most clients were aged 0–9 years. More than a third were Indigenous. Victoria had the greatest number of clients and the Northern Territory had the highest rate of clients per 10,000 population. The majority of clients had previously been assisted by a SHS agency since July 2011. Half were at risk of homelessness at the start of support. Most were in major cities.

Care arrangement type

Children on care and protection orders may reside with their parents or in placements approved by each state or territory’s child protection authority where they are unable to live with their families due to safety concerns.

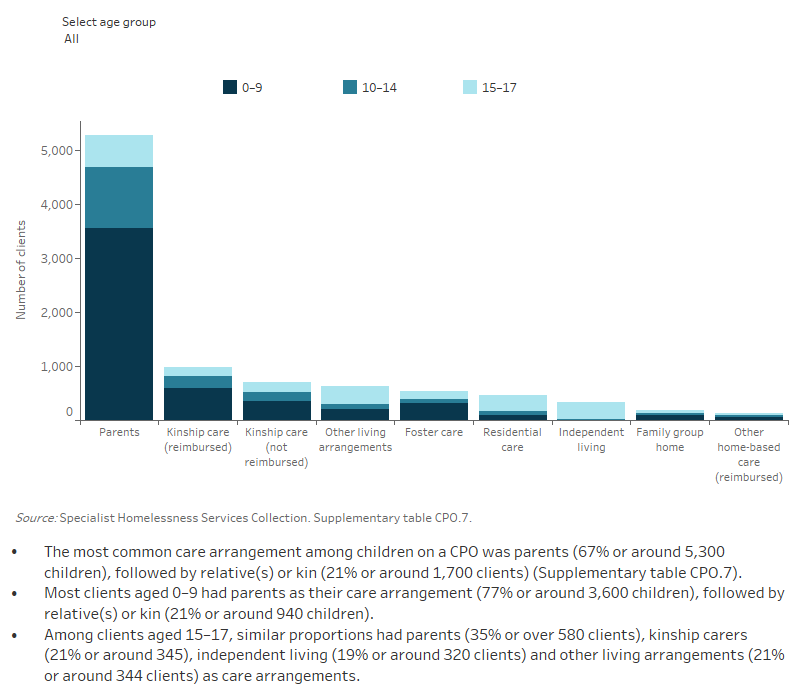

Figure CPO.2: Children on care and protection orders, by placement type, 2021–22

This interactive stacked bar graph shows children on a care and protection order by placement type and age group. The most common care arrangement was with parents, followed by kinship care, other living arrangements, foster care, residential care, independent living, family group home and other home-based care.

Selected vulnerabilities

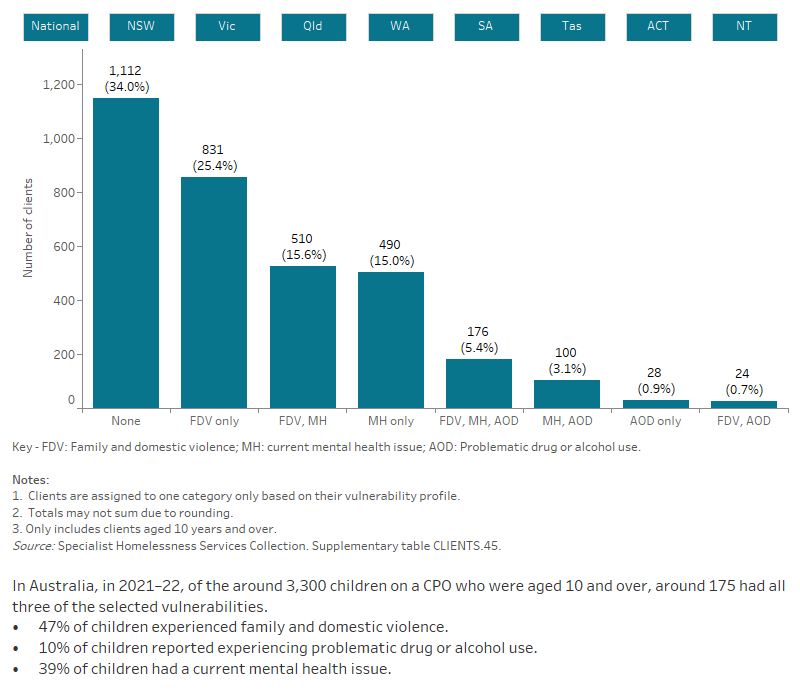

Children on a CPO may face additional vulnerabilities that make them more susceptible to becoming homeless, in particular family and domestic violence, a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use. These vulnerabilities are only assessed in clients aged 10 and over.

Figure CPO.3: Children on care and protection orders, by selected vulnerabilities, 2021–22

|

This interactive bar graph shows the number of children on a care and protection order also experiencing additional vulnerabilities, including experiencing family and domestic violence, having a current mental health issue and problematic drug and/or alcohol use. The graph shows both the number of clients experiencing a single vulnerability only, as well as combinations of vulnerabilities, and presents data for each state and territory. |

Service use patterns

Over the 5 years to 2021–22, the median length of support for children on care and protection orders increased from 97 days in 2017–18 to 113 days in 2021–22. However, the average number of support periods per client remained constant over time from an average of 1.8 support periods per client in 2017–18 to 1.7 in 2021–22.

The proportion of clients receiving accommodation decreased from 51% in 2017–18 to 47% in 2021–22, while the median number of nights accommodated increased from 66 in 2017–18 to 93 in 2021–22 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.46).

New or returning clients

Around 3 in 5 of the children on a CPO (59% or around 4,600 clients) were returning clients (Supplementary table CLIENTS.40) having received assistance from a SHS agency at some point since the collection began in July 2011. Returning clients were more likely than new clients to be aged 10–17 (42%, compared with 40%), conversely new clients were more likely to be aged 0–9 years (60% compared with 58% of returning clients).

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2021–22, the most common main reasons for seeking assistance among children on a CPO were (Supplementary table CPO.5):

- family and domestic violence (38% or over 2,900 clients)

- housing crisis (19% or around 1,500 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (9.3% or over 700 clients).

Family and domestic violence was the most common main reason for seeking assistance for both homeless and at risk children on a CPO, though the proportion was much higher for children at risk (47% or nearly 1,700 clients, compared with 26% or just over 900) (Supplementary table CPO.6).

Services needed and provided

Similar to the overall SHS population, most children on a CPO needed general services, including advice/information, advocacy/liaison on behalf of client and other basic assistance and these were mostly provided by SHS agencies (Supplementary table CPO.2).

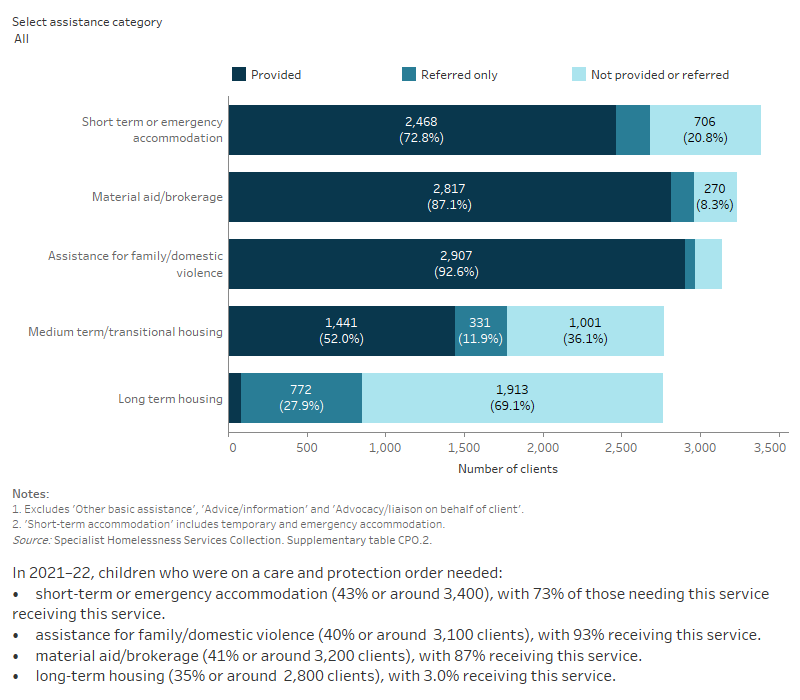

Figure CPO.4: Children on care and protection orders, by services needed and provided, 2021–22

|

This interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the services needed by children on a care and protection order and their provision status. Advice/information was the most needed and most provided service. Long term housing was the least provided service. |

Children on a CPO were also more likely than the overall SHS population to need services including (Supplementary tables CPO.2 and CLIENTS.24):

- child protection services (23%, compared with 4.6%), with 74% receiving this service

- assistance for family/domestic violence (40%, compared with 28%), with 93% receiving this service

- advocacy/liaison on behalf of the client (65%, compared with 54%), with 97% receiving this service

- family/relationship assistance (24%, compared with 13%), with 81% receiving this service

- transport (24%, compared with 15%), with 92% receiving this service.

Housing situation and outcomes

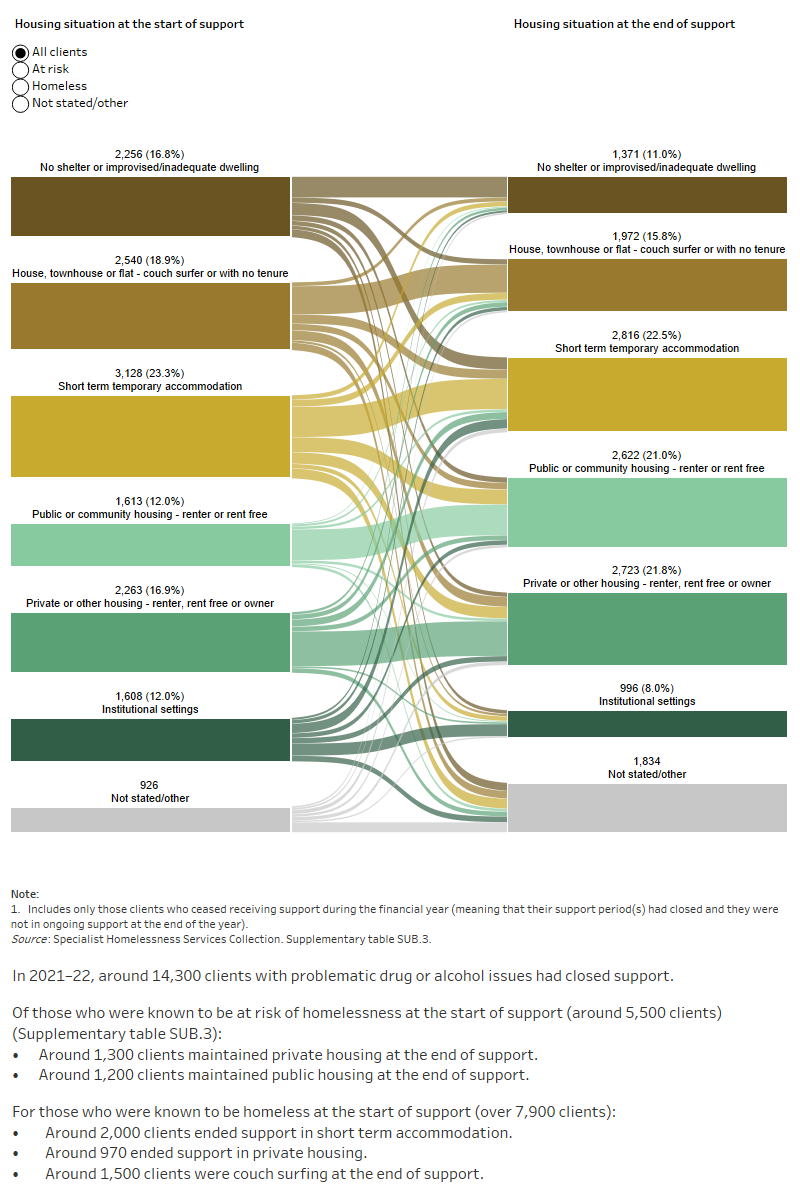

Outcomes presented here highlight the changes in clients’ housing situation at the start and end of support. That is, the place they were residing before and after they were supported by a SHS agency. The information presented is limited only to clients who have stopped receiving support during the financial year, and who were no longer receiving ongoing support from a SHS agency. In particular, information on client housing situations at the start of their first period of support during 2021–22 is compared with the end of their last period of support in 2021–22. As such, this information does not cover any changes to their housing situation during their support period.

For children on a care and protection order in 2021–22, around 2,000 children (49%) were experiencing homelessness at the start of support. Of these, 1,100 (27%) were in short-term temporary accommodation (Figure CPO.3, Supplementary table CPO.3).

By the end of support, many clients have achieved or progressed towards a more positive housing solution. That is, the number and/or proportion of clients ending support in public or community housing (renter or rent-free) or private or other housing (renter or rent-free) had increased compared with the start of support (Supplementary table CPO.4):

- More than 2 in 5 (41% or 780 clients) children on a care and protection order who were experiencing homelessness at the start of support were housed.

- More than 1 in 5 were living in private rental accommodation (410 clients or 22%).

- For those at risk of homelessness, almost 9 in 10 (1,700 clients or 85%) were housed; mostly in private rental accommodation (1,100 clients or 54%).

Figure CPO.5: Housing situation for children on a care and protection order with closed support, 2021–22

|

This interactive Sankey diagram shows the housing situation (including rough sleeping, couch surfing, short-term accommodation, public/community housing, private housing and institutional settings) of children on a care and protection order with closed support periods at first presentation and at the end of support. The diagram shows clients’ housing situation journey from start to end of support. Most started and ended support in private housing. |

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2016) Vulnerable young people: interactions across homelessness, youth justice and child protection – 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2015, AIHW website.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022) Child protection Australia 2020–21, AIHW website.

MICAH Projects (2016) Families caught in the homelessness and child protection cycle: a supportive housing model for keeping families together, Common Ground Queensland.

Noble-Carr D and Trew S (2018) Nowhere to go: investigating homelessness experiences of 12–15 year olds in the Australian Capital Territory, Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University.