Clients with a current mental health issue

On this page

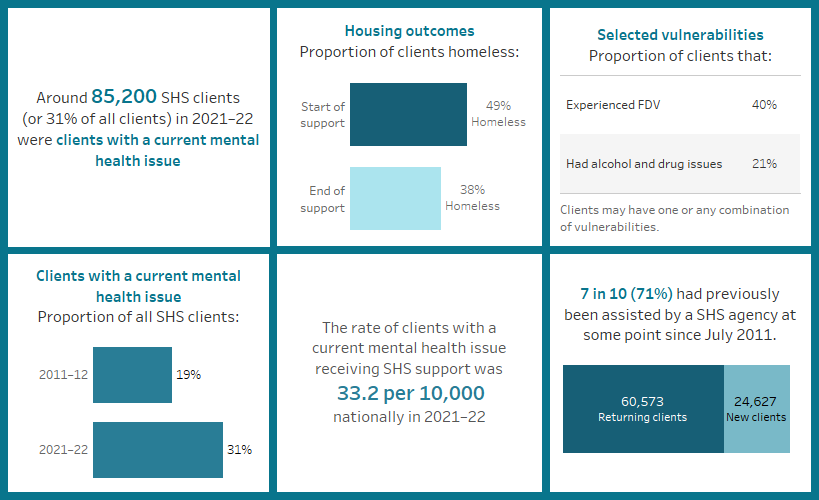

Key findings: Clients with a current mental health issue, 2021–22

Mental health is fundamental to the health and wellbeing of individuals, their families, and the population at large (Schulz and Sherwood 2008; WHO 2018). Mental health is “a state of well-being in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (WHO 2018). Conversely, a mental illness is a “clinically diagnosable disorder that significantly interferes with a person’s cognitive, emotional or social abilities” (DHAC 2012).

The term ‘mental health issues’ captures the entire range of mental health problems and as such, clients with a current mental health issue are a diverse group, as each person may have different symptoms and circumstances.

Mental health issues are common in Australia. In 2021, 1 in 5 (21%) Australians (aged 16–85) experienced a mental health condition within the past year. People with mental health issues are especially vulnerable to experiencing homelessness (Brackertz et al. 2020). The environmental stresses that often come with experiencing housing instability or homelessness can trigger, exacerbate, or magnify mental health issues (Johnson & Chamberlain 2016). Symptoms of mental illnesses that increase psychological distress and impair decision-making in everyday life can contribute to worse health outcomes, reduced support, and experiences of financial hardship, as well as homelessness (Brackertz et al. 2018; Johnstone et al. 2016; Kaleveld et al. 2018; Walter et al. 2016). In this way, mental health issues can contribute to entering – and maintaining – homelessness, while experiencing homelessness itself can lead to mental health issues.

People with a history of homelessness (2 in 5 or 39%) experience mental health conditions at a rate almost double of that of the general population (21%) (ABS 2022). Also, people with a mental health issue are more likely to experience homelessness (Nilsson et al 2019).

Defining clients with a mental health issue in the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC)

Specialist Homelessness Services (SHS) clients are identified as having a current mental health issue if they are aged 10 years or older and have provided any of the following information:

- They indicated that at the beginning of support they were receiving services or assistance for their mental health issues or had in the last 12 months.

- Their formal referral source to the SHS was a mental health service.

- They reported ‘mental health issues’ as a reason for seeking assistance.

- Their dwelling type either a week before presenting to an agency, or when presenting to an agency, was a psychiatric hospital or unit.

- They had been in a psychiatric hospital or unit in the last 12 months.

- At some stage during their support period, a need was identified for psychological services, psychiatric services or mental health services.

Client characteristics

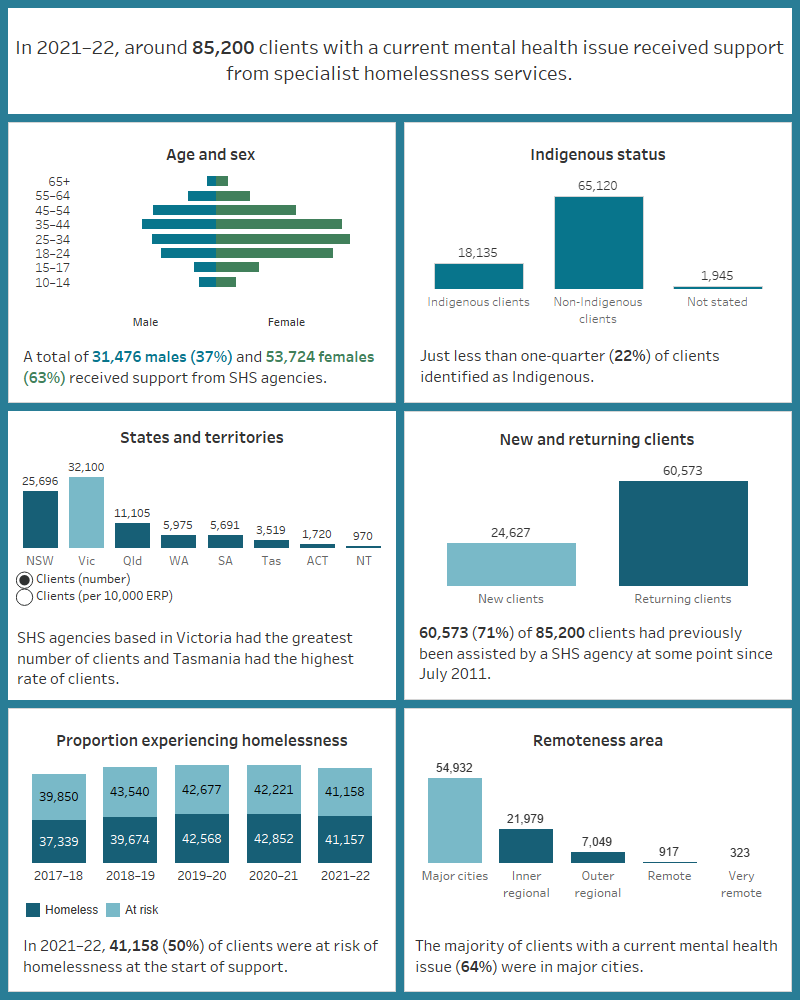

Figure MH.1: Key demographics, SHS clients with a current mental health issue, 2021–22

This image describes the characteristics of around 85,200 clients with a current mental health issue and received SHS support in 2021–22. Most clients were female, aged 18–44. Less than a quarter were Indigenous. Victoria had the greatest number of clients and Tasmania had the highest rate of clients per 10,000 population. The majority of clients had previously been assisted by a SHS agency since July 2011. Half were at risk of homelessness at the start of support. Most were in major cities.

Living arrangements and presenting unit type

Of the 85,200 clients with a current mental health issue in 2021–22, most clients presented to a SHS agency alone (81% or 69,100 clients) and lived alone at the beginning of support (47% or 39,000 clients). Around one-quarter of clients were living as a single parent with child/ren (24%) (Supplementary tables CLIENTS.42 and CLIENTS.43).

Labour force status

Around 9 in 10 clients with a current mental health issue were not working in a paid job (87% or 65,800 clients) in 2021–22. More than half (54%) of clients were looking for work (that is, unemployed) and one-third (33%) were not in the labour force. Only around 1 in 10 clients (13%) with a current mental health issue were employed (Supplementary table MH.7).

Selected vulnerabilities

More than half of clients with a current mental health issue (52% or 44,300 clients) experienced another type of vulnerability in 2021–22 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.45). Given clients with a current mental health issue also often experience multiple different types of vulnerabilities, this highlights the value of an integrated service response to homelessness for these clients (Flatau et al. 2022).

Figure MH.2: Clients with a current mental health issue, by selected vulnerability characteristics, 2021–22

The interactive bar graph shows proportions of clients with a current mental health issue also experiencing additional vulnerabilities, including experiencing family and domestic violence and problematic drug and/or alcohol use. The graph shows both the number of clients experiencing a single vulnerability only, as well as combinations of vulnerabilities, and presents data for each state and territory.

Service use patterns

The length of support that clients with a current mental health issue received in 2021–22 increased to a median of 90 days from 85 days in 2020–21. Similarly, the median number of nights accommodated increased to 51 nights in 2021–22 from 48 nights in 2020–21 (Supplementary table CLIENTS.46).

Changes over time since 2011–12

The number of clients with a current mental health issue receiving assistance from SHS agencies has increased at a faster rate than any other client group since the collection began in July 2011. Both the number and proportion of clients with a current mental health issue have also for the most part increased with each successive year.

Between 2011–12 and 2021–22 (Supplementary table HIST.MH):

- The proportion of clients with a current mental health issue increased from around one-fifth (19%) to almost one-third (31%) of all SHS clients.

- The number of clients with a current mental health issue increased by an average of 6.7% with each year; an annual change around 3 times higher than that for all SHS clients (1.4%) over the same period.

- The rate of SHS clients with a current mental health issue increased from 20.0 clients per 10,000 population to 33.2.

New or returning clients

In 2021–22, among SHS clients with a current mental health issue (Supplementary table CLIENTS.40):

- 7 in 10 (71% or 60,600 clients) were returning clients, that is, returning clients received assistance from a SHS agency in the past (from 2011 onwards).

- 3 in 10 (29% or 24,600 clients) were new to SHS agencies.

Main reasons for seeking assistance

In 2021–22, the main reason that clients with a current mental health issue sought assistance from a SHS agency was not commonly related to mental health issues (4.1% or 3,500 clients). Instead, the main reasons for seeking assistance were for (Supplementary table MH.5):

- housing crisis (21% or 18,200 clients)

- family and domestic violence (19% or 16,500 clients)

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (13% or almost 11,100 clients).

The most common main reason(s) clients with a current mental health issue sought assistance differed slightly depending on whether the clients were at risk of homelessness or were experiencing homelessness when they first presented to a SHS agency. For those experiencing homelessness, the main reason was housing crisis (24% or 9,800 clients), while for those at risk of homelessness it was family and domestic violence (25% or 10,100) (Supplementary table MH.6).

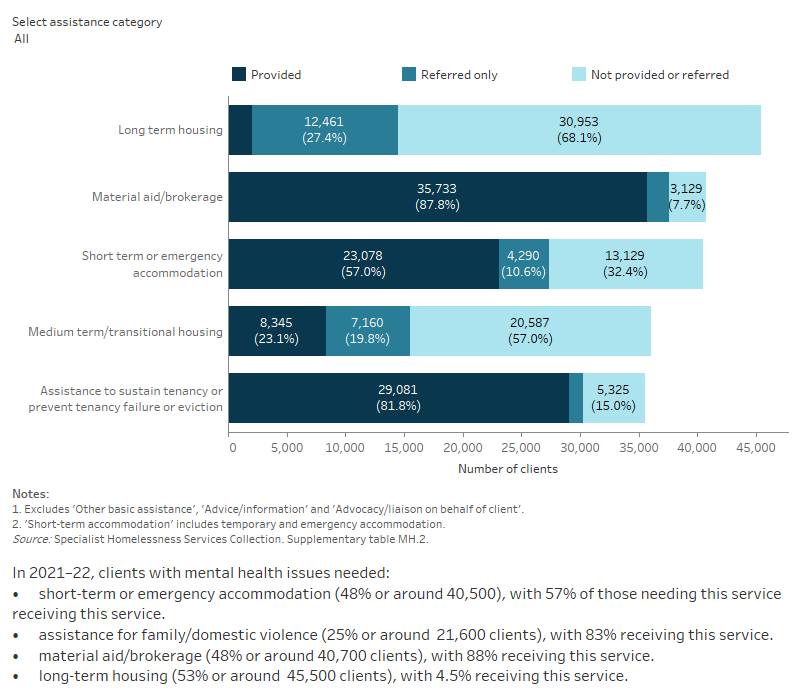

Services needed and provided

In 2021–22, most clients with a current mental health issue needed assistance with accommodation provision (70%), though other common assistance sought included general and financial advice and advocacy. Assistance with accessing mental health services was also relatively common, with more than one-quarter (27% or 23,000) of clients with a current mental health issue needing assistance with mental health-based services (Supplementary table MH.2). Specifically:

- 25% (21,000 clients) needed mental health services; 45% (9,500 clients) of these clients were provided with this type of service.

- 9.1% (almost 7,800 clients) identified a need for psychological services; 31% (2,400 clients) of these clients had this need met.

- 5.9% (5,100 clients) identified a need for psychiatric services; 34% (1,700 clients) of these clients had this need met.

Figure MH.3: Clients with a current mental health issue, by services needed and provided, 2021–22

This interactive stacked horizontal bar graph shows the services needed by clients with a current mental health issue and their provision status. Advice/information and assistance to sustain tenancy or prevent tenancy failure or eviction were the most provided services. Long term housing was the least provided service.

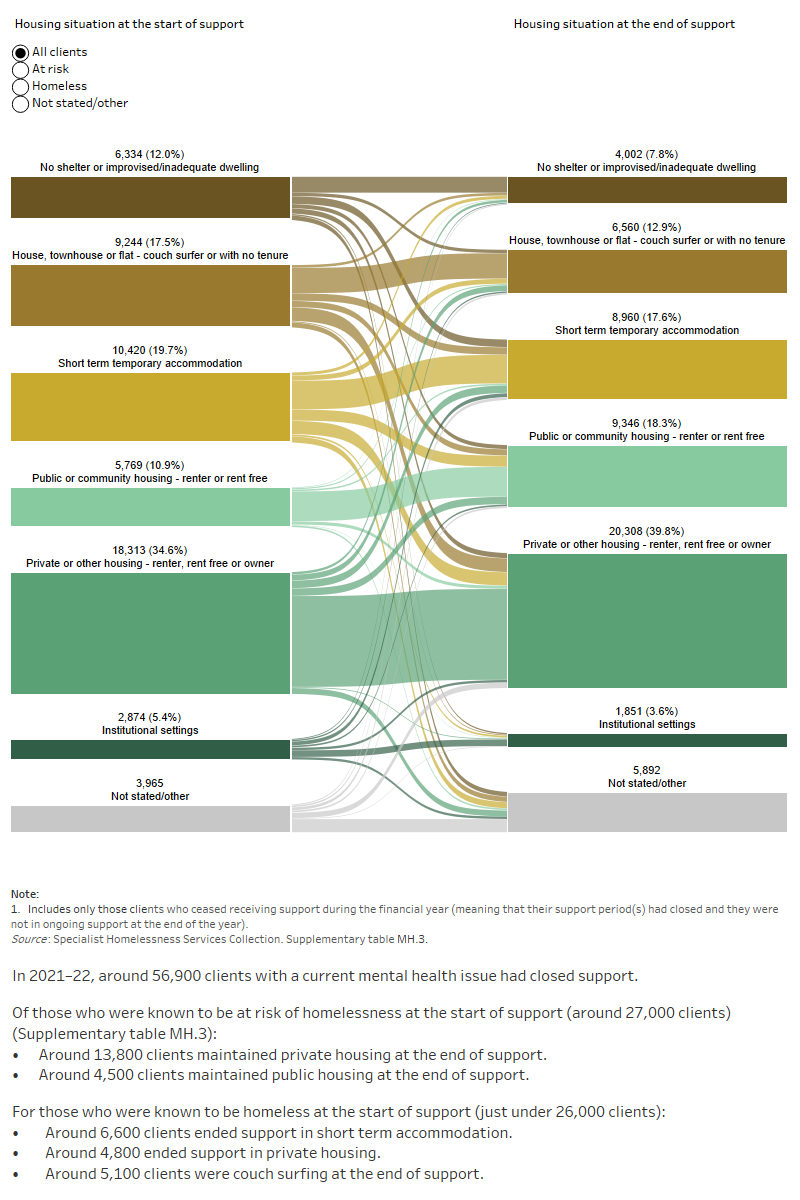

Housing situation and outcomes

Outcomes presented here highlight the changes in clients’ housing situation at the start and end of support. That is, the place they were residing before and after they were supported by a SHS agency. The information presented is limited only to clients who have stopped receiving support during the financial year, and who were no longer receiving ongoing support from a SHS agency. In particular, information on client housing situations at the start of their first period of support during 2021–22 is compared with the end of their last period of support in 2021–22. As such, this information does not cover any changes to their housing situation during their support period.

In 2021–22, half (49% or 26,000 clients) of clients with a current mental health issue were experiencing homelessness at the start of support; around 6,300 (12%) were rough sleeping – one of the highest proportions of this housing type among the SHS client groups (Supplementary table MH.3).

By the end of support, fewer clients with a current mental health issue were known to be experiencing homelessness (38%) (Supplementary table MH.4):

- Around 3 in 5 clients (62% or 30,300 clients) were living in stable accommodation, such as public or community housing or private housing.

- More than one-third (37% or 8,700 clients) of clients experiencing homelessness at the start of support were housed.

Figure MH.4: Housing situation for clients with a current mental health issue with closed support, 2021–22

This interactive Sankey diagram shows the housing situation (including rough sleeping, couch surfing, short-term accommodation, public/community housing, private housing and institutional settings) of clients with a current mental health issue with closed support periods at first presentation and at the end of support. The diagram shows clients’ housing situation journey from start to end of support. Most started and ended support in private housing.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) ’12-month mental disorders’ [dataset], National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, ABS website, accessed 05 September 2022.

Brackertz N, Borrowman L, Roggenbuck C, Pollock S and Davis E (2020) Trajectories: the interplay between mental health and housing pathways: Final research report, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited (AHURI) and Mind Australia.

Brackertz N, Wilkinson A and Davison J (2018) Housing, homelessness and mental health: towards systems change Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2012) Glossary, DHAC website, accessed 7 September 2022.

Flatau P, Lester L, Seivwright A, Teal R, Dobrovic J, Vallesi S, Hartley C and Callis Z (2022) Ending Homelessness in Australia: an evidence and policy deep dive, Centre for Social Impact, doi:10.25916/ntba-f006.

Johnson G and Chamberlain C (2016) ‘Are the Homeless Mentally Ill?’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, 46(1):29-48.

Johnstone M, Parsell C, Jetten J, Dingle G and Walter Z (2016) ‘Breaking the cycle of homelessness: Housing stability and social support as predictors of long-term well-being’, Housing Studies, 31(4):410-426, doi: 10.1080/02673037.2015.1092504.

Kaleveld L, Seivwright A, Box E, Callis Z and Flatau P (2018) Homelessness in Western Australia: A review of the research and statistical evidence, Government of Western Australia, Department of Communities.

Nilsson SF, Nordentoft M and Hjorthøj C (2019) ‘Individual-Level Predictors for Becoming Homeless and Exiting Homelessness: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis’, Journal of Urban Health, 96(5):741-750, doi: 10.1007/s11524-019-00377-x.

Schulz R and Sherwood PR (2008) ‘Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving’, The American journal of nursing, 108(9):23–27, doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c.

Walter ZC, Jetten J, Dingle GA, Parsell C & Johnstone M (2016) ‘Two pathways through adversity: Predicting well‐being and housing outcomes among homeless service users’, British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(2):357-74. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12127

World Health Organization (2018) Mental Health: Strengthening our response, WHO website, accessed 06 September 2022.