Patient safety

This section presents data for the patient safety indicators supplied by Australia to the HCQO collection. It compares these data with the HCQO results for other OECD countries, and comments on the comparability of the data provided to the OECD specification (OECD 2021).

Patient safety remains a pressing issue in the delivery of health services, with over 15% of hospital expenditure and activity in OECD countries attributable to treating patients who experienced a safety event, many of which are preventable (OECD 2021). Patient safety indicators screen for events that patients experience during their hospital stays as a result of exposure to the health-care system – either adverse events that cannot be totally avoided or events that should never occur (OECD 2021).

The OECD published all patient safety indicators in OECD.Stat and a selection of patient safety indicators in Health at a glance 2021. Australia submitted results for all 7 patient safety indicators in the data collection:

- Retained surgical item or unretrieved device fragment

- Post-operative wound dehiscence

- Post-operative pulmonary embolism – hip and knee replacement discharges

- Post-operative deep vein thrombosis – hip and knee replacement discharges

- Post-operative sepsis – abdominal discharges

- Obstetric trauma after vaginal delivery with instrument

- Obstetric trauma after vaginal delivery without instrument.

The indicator definitions can be viewed here: patient safety indicator definitions

Overall data comparability and methods

The most recent data supplied by Australia for the patient safety indicators were for 2018–19. These data are recorded as 2018 data in the OECD.Stat database, and so are described in that way here. Data from other OECD countries published on OECD.Stat for 2018 are used for comparison and calculation of OECD averages in this section. These data were extracted from the OECD.Stat database in November 2021, and may not reflect subsequent updates made to the database.

Patient safety rates reported by the OECD were for adults aged 15 and over and were not age-sex standardised. The indicators are presented on the same basis here.

It should be noted that data from the AIHW’s National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD) are collected primarily for the purposes of recording care provided to admitted patients, and that use of the data for HCQO purposes has not been validated for accuracy in Australia. The results should therefore be treated with caution. Health at a glance 2021 notes that ‘variations in definitions and medical recording practices between countries can affect calculation of rates and limit data comparability in some cases’ (OECD 2021:28). It further notes that ‘higher adverse event rates may signal more developed patient safety monitoring systems and a stronger patient safety culture rather than worse care’ (OECD 2021:28).

In Australia, there is a lack of financial disincentives connected to the reporting of adverse events, and this may have contributed to some relatively high rates reported for Australia. It is also possible that efforts to improve coding quality and to improve the focus on patient safety in Australia in recent years could have led to increased reporting of patient safety events in Australia compared with some other OECD countries.

A number of features of Australian patient safety monitoring would support the claim that Australia is one of those countries that has a more developed patient safety monitoring system. Australia employs specially trained staff to identify and code information from patient records. It is also likely that in Australia additional diagnoses are generally well recorded at the national level due to the ability to record up to 99 additional diagnoses for reporting to the NHMD.

The AIHW endeavoured to apply all specifications as supplied by the OECD; however, there were some parts where this was not able to be achieved. The OECD specifications for the patient safety indicators requested identification of readmissions in order to identify any subsequent related admissions to hospital within 30 days of the original hospital admission, as some adverse events are likely to manifest in the period following discharge from hospital. Australia’s national data collection for admitted patients (the NHMD) is based on a single episode of care as the statistical unit (as described in the Acute care section). Therefore, Australia was unable to meet this requirement, and could only include instances that occurred within the one (hospital) episode of care in the calculations of the patient safety indicators.

The OECD specifications also requested the exclusion of some cases where the condition of interest was present on admission; however, due to data quality issues, the AIHW did not do this, as not all cases that arose during the episode were flagged as such.

Retained surgical item or unretrieved device fragment

Sentinel events are a subset of adverse patient safety events that are wholly preventable and result in serious harm to, or death of, a patient (ACSQHC 2020). The ‘unintended retention of a foreign object in a patient after surgery or other invasive procedure resulting in severe harm or death’ is listed as one of the top 10 national sentinel events in Australia (ACSQHC 2020).

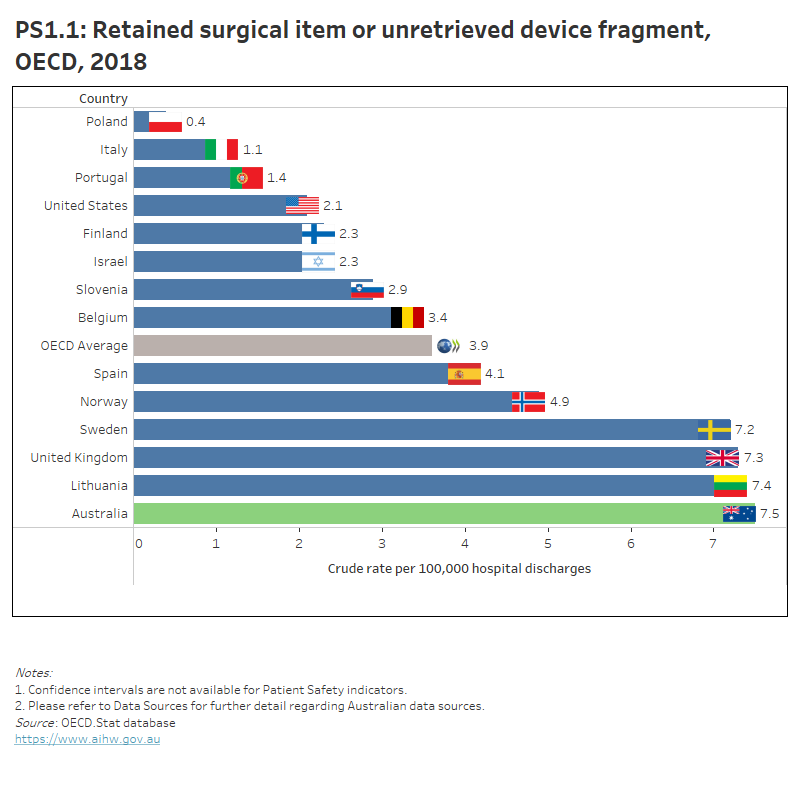

In Australia, the rate of retained surgical item or unretrieved device fragment for people aged 15 and over was 7.5 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2018. The rate has fluctuated over time in the past decade, ranging from 9.7 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2013 to 7.4 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2015.

Australia had the highest rate of retained foreign object among OECD countries that submitted data for 2018. The OECD average was 3.9 per 100,000 hospital discharges, and Poland (0.4 per 100,000 hospital discharges) had the lowest rate.

Interactive PS1.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for this indicator for 2018, while PS1.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

PS1.1 presents OECD countries with data available for retained surgical item or unretrieved device fragment indicator in 2018, which shows Australia had the highest rate. PS1.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows a fluctuating trend over time.

Refer to the data tables for more information.

Post-operative wound dehiscence

The post-operative wound dehiscence indicator measures wound ruptures along the surgical suture. This could result in fever, haematoma, seroma, separation of wound edges, and purulent discharge from the wound (Yao et al. 2013).

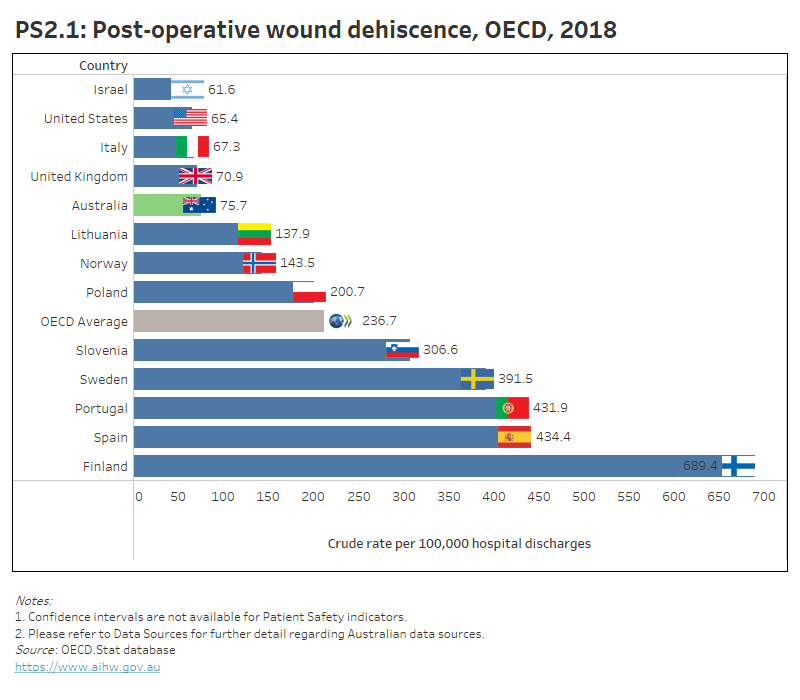

In Australia, the post-operative wound dehiscence rate was 76 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2018, a decrease from 131 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2009.

Australia’s rate was lower than the OECD average of 237 per 100,000 hospital discharges. Israel (62 per 100,000 hospital discharges) had the lowest rate.

Abdominopelvic procedure codes were required for the calculation of this indicator. The AIHW found that mapping was not straightforward in this instance, as the ICD-9-CM codes supplied by the OECD did not map directly to the ACHI code list used in Australia. The effect of this on the comparability of data is unknown.

Interactive PS2.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for this indicator for 2018, while PS2.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

PS2.1 presents OECD countries with data available for post-operative wound dehiscence indicator in 2018, which shows Australia had a lower rate than the OECD average. PS2.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows a decrease since 2009.

Refer to the data tables for more information.

Post-operative pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis – hip and knee replacement discharges

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a blood clot that breaks off from the deep veins and travels round the circulatory system to block the arteries in the lung. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blockage in the deep veins of the legs, thighs or pelvis, caused by the clotting of blood. Most deaths arising from DVT are caused by PE (NICE 2018).

The risk of PE and DVT following hip and knee replacement procedures is higher than following other surgical procedures (OECD 2013). Both conditions may result in pain, decreased mobility, and sometimes death, but both can be prevented by anticoagulants and other measures (OECD 2021).

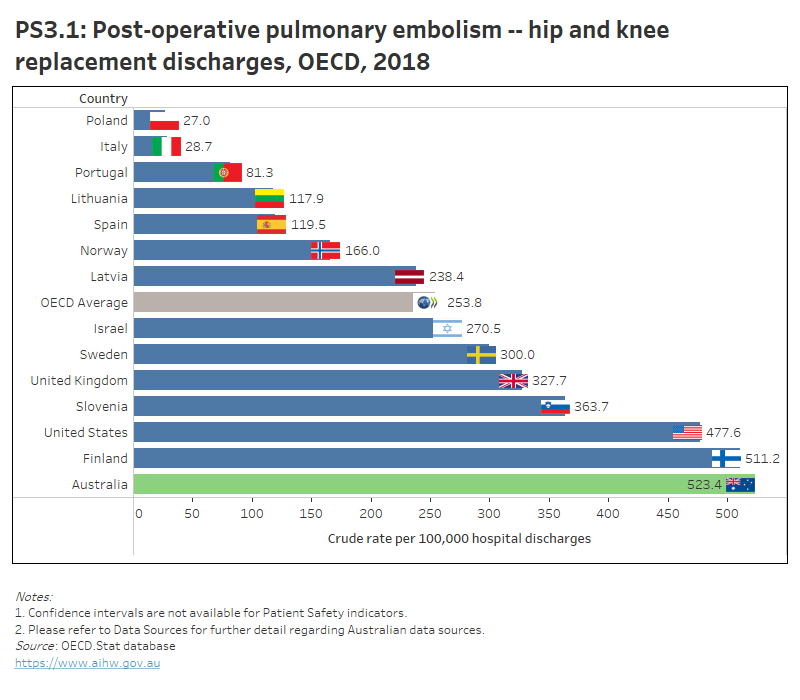

In 2018, Australia had the highest rate of PE after hip and knee replacement discharges (523 per 100,000 hospital discharges) for people aged 15 and over among OECD countries that submitted data. This rate has fluctuated over time in the past decade, ranging from 560 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2013 to 472 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2015.

The OECD average in 2018 was 254 per 100,000 hospital discharges. Poland (27 per 100,000 hospital discharges) had the lowest rate.

Interactive PS3.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for 2018 for this indicator, while PM3.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

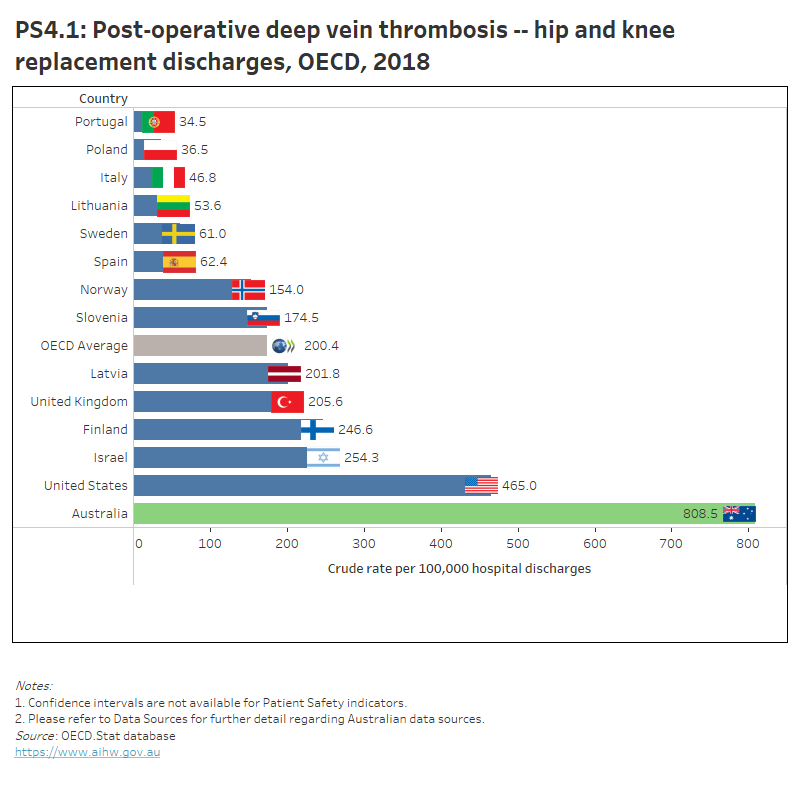

Australia also had the highest rate of DVT after hip and knee replacement discharges (808.5 per 100,000 hospital discharges) for people aged 15 and over among OECD countries that submitted data for 2018. The overall trend in Australia shows a decrease from 1,171 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2010.

The OECD average was 200 per 100,000 hospital discharges, and Portugal had the lowest rate (34.5 per 100,000 hospital discharges).

Interactive PS4.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for 2018 for this indicator, while PM4.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

Health at a glance 2021 notes that there were large variations in the data reported for both indicators. These variations were concluded to be likely to reflect differences in diagnostic practices across countries (OECD 2021).

PS3.1 presents OECD countries with data available for post-operative PE in hip and knee replacement discharges indicator in 2018, which shows Australia had the highest rate. PS3.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows a fluctuating trend over time.

PS4.1 presents OECD countries with data available for post-operative DVT in hip and knee replacement discharges indicator in 2018, which shows Australia had the highest rate. PS4.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows a decrease since 2010.

Refer to the data tables for more information.

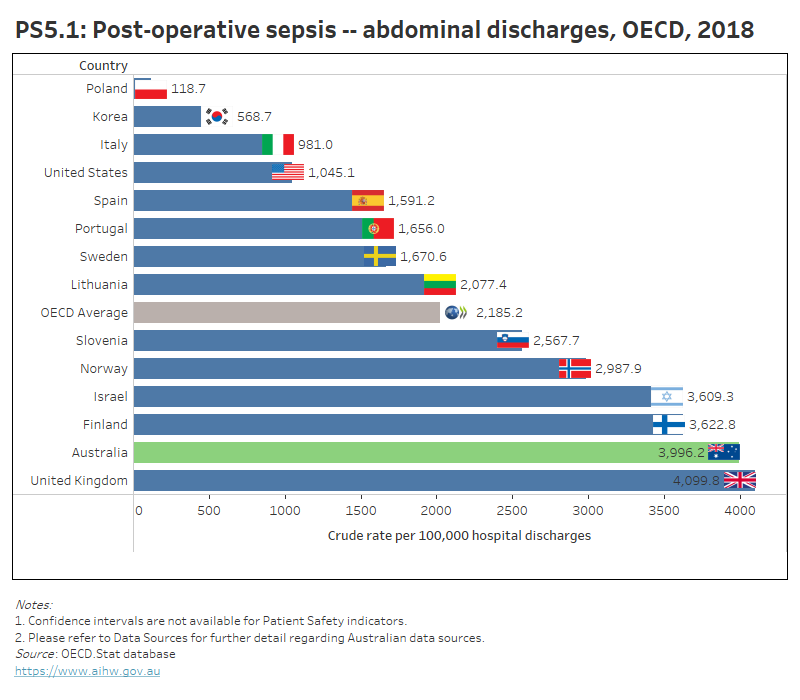

Post-operative sepsis – abdominal discharges

Sepsis is the systematic response to an infection manifested by organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion or hypotension combined with one or more of the following: fever, tachypnoea, elevated white cell count (Antibiotic Expert Groups 2014). In many cases, post-operative sepsis can be prevented by prophylactic antibiotics, sterile surgical techniques, and good postoperative care (OECD 2017). The risk of sepsis following abdominal surgery is greater than following other surgical procedures (OECD 2015).

In Australia, the post-operative sepsis rate for abdominal discharges among people aged 15 and over was 3,996 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2018. This shows an increase from 2,641.5 per 100,000 hospital discharges in 2011.

Australia had the second highest rate among OECD countries that submitted data, behind the United Kingdom (4,100 per 100,000 hospital discharges). The OECD average was 2,185 per 100,000 separations, and Poland had the lowest rate (119 per 100,000 hospital discharges).

Abdominopelvic procedure codes were required for the calculation of this indicator. The AIHW found that mapping was not straightforward in this instance as the ICD-9-CM codes supplied by the OECD did not map directly to the ACHI code list used in Australia. The effect of this on the comparability of data is unknown.

Interactive P5.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for this indicator for 2018, while PS5.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

PS5.1 presents OECD countries with data available for post-operative sepsis in abdominal discharges in 2018, which shows Australia had the 2nd highest rate. PS5.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows an increase since 2011.

Refer to the data tables for more information.

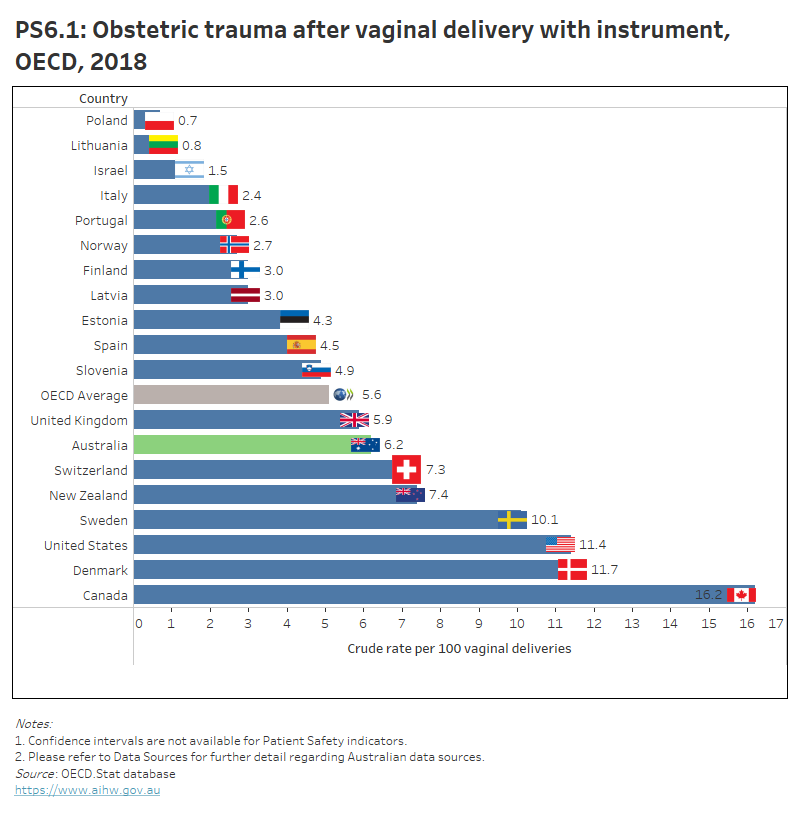

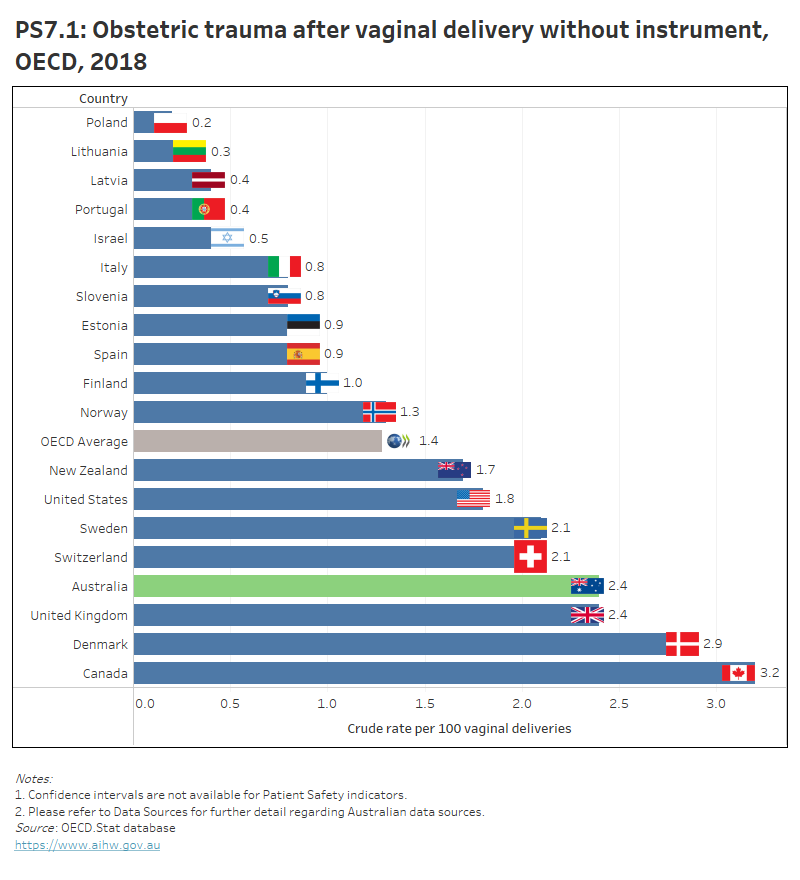

Obstetric trauma with and without instrument

A woman’s safety during childbirth can be assessed by looking at potentially preventable, severe tearing of the perineum during vaginal delivery (OECD 2021). These types of tears cannot be completely prevented, but can be reduced through appropriate labour management and high quality obstetric care (OECD 2021).

The obstetric trauma with and without instrument indicators measure third and fourth-degree tearing of the perineum during instrument-assisted (such as use of forceps or vacuum extraction) or non-assisted vaginal deliveries.

In 2018, 6.2 per 100 instrument-assisted vaginal deliveries in Australia experienced severe obstetric trauma – a decrease from 7.7 per 100 vaginal deliveries in 2010.

This rate was higher than the OECD average of 5.6 per 100 vaginal deliveries. Poland (0.7 per 100 vaginal deliveries) had the lowest obstetric trauma rate.

Interactive PS6.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for 2018 for this indicator, while PS6.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

In 2018, Australia and the United Kingdom had the equal third highest rate of obstetric trauma for non-assisted vaginal deliveries (2.4 per 100 vaginal deliveries), behind Canada and Denmark (3.2 and 2.9 per 100 vaginal deliveries, respectively). In Australia, this rate has remained relatively stable since 2010.

The OECD average was 1.4 per 100 vaginal deliveries. Poland had the lowest rate (0.2 per 100 vaginal deliveries).

Interactive PS7.1 below compares OECD countries that submitted data for 2018 for this indicator, while PM7.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator.

PS6.1 presents OECD countries with data available for obstetric trauma with instrument indicator in 2018, which shows Australia had a higher rate than the OECD average. PS6.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows a gradual decrease since 2010.

PS7.1 presents OECD countries with data available for obstetric trauma without instrument indicator in 2018, which shows Australia had the 3rd highest rate. PS7.2 presents Australia’s 10-year trend for this indicator, which shows a stable trend since 2010.

Refer to the data tables for more information.

ACSQHC (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care) 2020. Australian sentinel events list. Version 2. Sydney: ACSQHC. Viewed 14 September 2021.

Antibiotic Expert Groups 2014. Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic. Version 15. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited.

OECD 2013. Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

OECD 2015. Health at a glance 2015: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

OECD 2017. Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

OECD 2021. Health at a glance 2021: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) 2018. Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. NG 89. London: NICE. Viewed 14 September 2021.

Yao L, Bae L and Yew WP 2013. Post-operative wound management. Australian Family Physician 42(12):867–70.