Palliative care outcomes

On this page:

In 2022, 61,100 patients received palliative care from the 180 palliative care services voluntarily participating in the Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC) program. This section provides information on the characteristics and outcomes for patients receiving palliative care from the palliative care services participating in PCOC over the period 2018 to 2022.

Note, as participation in PCOC is voluntary, not all services participate in PCOC. The data presented in this section therefore describe a subset of all palliative care delivered in Australia. Further information about PCOC is described below and in the Data sources section.

The information in this section was last updated in November 2023.

The Australian Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC), established in 2005, is a national palliative care outcomes quality improvement program. The program uses standardised validated clinical assessment tools to benchmark and measure outcomes in palliative care, including pain and symptom control, and timely access to services when they are needed to drive quality improvements (see Data sources section for further details).

For the palliative care outcomes collection, data are captured at three levels – the patient-level, episode-level, and phase-level.

- Patient-level information describes demographics such as sex, Indigenous status, preferred language and country of birth, and the place in which the patient died.

- Episode-level information describes the setting of palliative care service provision. It also includes information relating to the facility or organisation that has referred the patient, and how an episode starts and ends.

- Phase-level information describes the clinical condition of the patient during the episode. This information is derived from five clinical tools. These tools include measures that examine palliative care phase, the patient’s functional status and performance status, symptom burden as assessed by examining symptom severity and distress, including pain and other common symptoms, the patient’s psychological/spiritual problems, and family/carer issues.

Information provided in this section is categorised into 2 broad settings of care –

- inpatient – admissions to hospital or hospice

- community – occurring in the patient’s 'home’. For example, this may be in their private residence or aged care.

Participation in PCOC is voluntary and contribution to the collection is sought from all palliative care service providers in public and private health sectors, across all regions, and across inpatient and community settings. However, not all services participate in PCOC. The data presented in this section therefore describes a subset of all palliative care delivered in Australia.

The PCOC data are provided by each participating palliative care service, using a standardised data submission process (a PCOC Version 3.0 Dataset Data Dictionary and Technical Guideline is made to assist with this process) (PCOC 2012). This process also involves standardised data quality checks and assurance procedures, which are completed by clinical, quality improvement and data experts. Further, a data quality statement, as informed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics Data Quality Framework, is also available. For further information about PCOC, refer to Australian Health Services Research Institute's PCOC information page.

Key points

In 2022, among 61,100 patients who received palliative care from the 180 palliative care services participating in PCOC program:

- 3 in 5 (63%) patients had a diagnosis of cancer

- 1 in 2 (52%) patients died – of these 67% died in hospitals, 22% at home and 10% in residential aged care facility

- 3 in 4 (77%) palliative care episodes ended within 30 days, with most ending within 2 weeks (62%)

- almost 9 in 10 (87%) unstable phases (urgent needs) were resolved within 3 days or less

- 9 in 10 palliative care phases that started with absent/mild patient pain remained absent/mild at the end of the palliative care phase – 89% for pain severity and 88% for distress from pain

- 3 in 5 palliative care phases that began with moderate/severe patient pain reduced to absent/mild by the end of the palliative care phase – 61% for pain severity and 58% for distress from pain.

Overview of patients, episodes of care and phases

PCOC defines a patient as a person for whom a palliative care service accepts responsibility for assessment and/or treatment as evidenced by the existence of a medical record.

In 2022, among 61,100 patients receiving palliative care from the 180 palliative care services participating in PCOC:

- more were men (52%) than women

- almost 2 in 3 (63%) had a diagnosis of cancer (Figure PCOC.1)

- 1 in 2 (52%) died – of these 67% died in hospital, 22% at home and 10% in residential aged care.

For further details on the characteristics of these patients, see Tables PCOC.1–3.

A palliative care episode is a period of contact between a patient and a service provider where palliative care is provided in a single setting (inpatient or community setting). A palliative care episode starts on the date a comprehensive palliative care assessment is undertaken and documented. An episode ends or is closed when the following occurs:

- setting of palliative care changes (for example community to inpatient)

- principal clinical intent of the care changes and the patient is no longer receiving palliative care

- the patient is formally separated from the service

- the patient dies.

A patient may have multiple palliative care episodes over the reference period if a patient’s care needs change, they no longer require palliative care, or they change settings. For example, if a patient receives care at home and then transitions to care in a hospital, this would be reflected as 2 separate episodes.

In 2022, there were 79,500 palliative care episodes reported to PCOC, equating to an average of 1.3 palliative care episodes per patient. Among these palliative care episodes:

- there were slightly more episodes in inpatient settings than in community settings (occurring in the patient’s usual residence, such as home or aged care) – 40,700 compared with 38,800, respectively (Table PCOC.1)

- median age at the start of the episode of care was 77 years (Table PCOC.4)

- almost 3 in 5 (56%) referrals were from public hospitals, and around 8% each from general practitioner, private hospital and community palliative care service (Figure PCOC.1).

There were 75,300 episodes that ended (closed episodes) in 2022. Among these closed episodes:

- 3 in 4 (77%) ended within 30 days, with most ending within 2 weeks (62%; Figure PCOC.1)

- inpatient episodes were generally shorter in duration than community episodes – with a median duration (elapsed days) of 4 days in inpatient setting compared with 21 days in community setting (Table PCOC.7):

- The proportion of inpatient episodes that ended within 2 days was 3 times as high as for community episodes (35% vs 11%) and twice as high for episodes that ended within 14 days (84% vs 37%, respectively).

- The proportion of community episodes that ended 15 days or after was 4 times as high as for inpatient episodes (63% vs 16%) and 9 times as high for episodes that ended 31 days or after (45% vs 4.8%, respectively).

- 1 in 2 (52%) inpatient episodes ended with the patient dying, while the corresponding proportion was 30% for community episodes. The most common reason for community episodes ending was the patient admitted for inpatient care, accounting for 1 in 2 (53%) episodes (Table PCOC.6).

A palliative care phase in PCOC identifies a clinically meaningful period in a patient’s condition, their functional ability, symptoms (including physical and psychological) and family/carer distress, using five brief clinical assessment tools. It is determined by a holistic clinical assessment which considers the needs of the patients, and their family and carers.

There are four types of palliative care phases included in PCOC:

- Stable: patient problems and symptoms are adequately controlled by an established plan of care, and

- further interventions to maintain symptom control and quality of life have been planned, and

- family/carer situation is relatively stable, and no new issues are apparent.

- Unstable: an urgent change in the plan of care or emergency treatment is required because:

- patient experiences a new problem that was not anticipated in the existing plan of care, and/or

- patient experiences a rapid increase in severity of a current problem, and/or

- family/carers circumstances change suddenly impacting on patient care.

- Deteriorating: the care plan is addressing anticipated needs but requires periodic review because the:

- patients overall functional status is declining, and/or

- patient experiences a gradual worsening of existing problem, and/or

- patient experiences a new but anticipated problem, and/or

- family/carers experience gradual worsening distress that impacts on the patient care.

- Terminal: death is likely within days (Masso et al. 2015; PCOC 2021).

It should be noted that palliative care phases are not necessarily sequential. A patient may transition back and forth between phases; therefore, it is likely that a patient will have more than one phase within an episode.

In 2022, there were 176,300 palliative care phases recorded in PCOC, with just over half (52%) occurring in community settings (91,000 compared with 85,300 in inpatient settings). On average, patients had 2.3 phases per closed episode (2.1 in inpatient settings compared with 2.6 in community settings) and 2.9 phases per patient (Table PCOC.1).

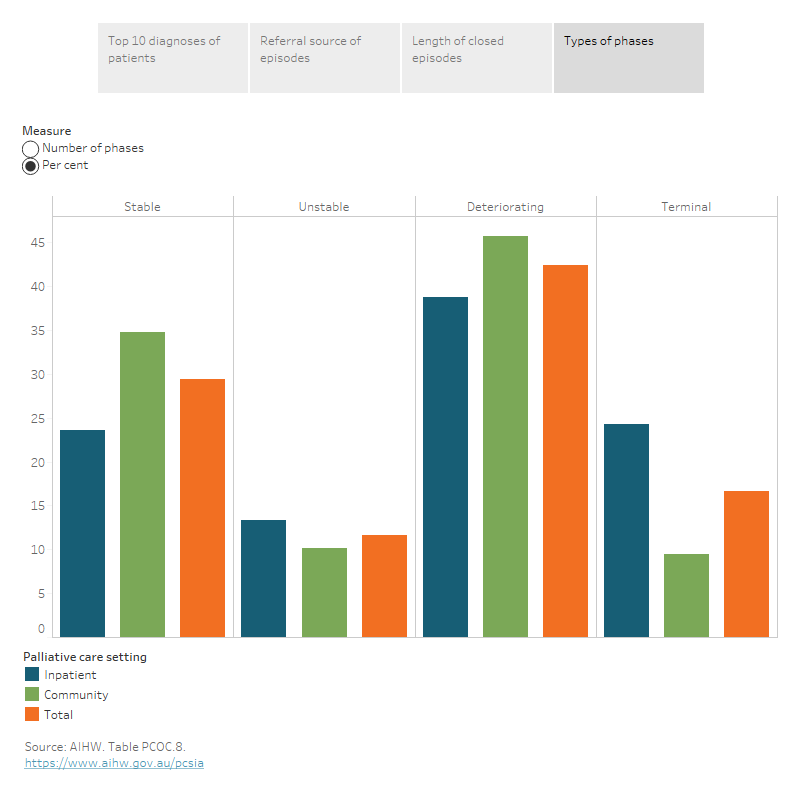

The 2022 data on palliative care phases revealed 3 main findings (Figure PCOC.1 and Table PCOC.8):

- 4 in 10 (42%) were deteriorating phases and 3 in 10 (29%) were stable phases, followed by terminal (17%) and unstable (12%) phases.

- Deteriorating and stable phases were more common for those in community settings (46% and 35%, respectively) than in inpatient settings (39% and 24%, respectively), while terminal and unstable phases were more common for those in inpatient settings (24% and 13% compared with around 10% each in community settings, respectively).

- The average length of each phase was longer for those in community than inpatient settings, particularly for those in stable and deteriorating phases where duration of the phase was 3.7 and 2.9 times as long for those in community settings than in inpatient settings – 21.7 days vs 5.8 days for stable phase and 14.0 days vs 4.8 days for deteriorating phase, respectively.

Figure PCOC.1: Overview of patients, episodes of care and phases for services participating in PCOC, 2022

Figure 1.1: The interactive data visualisation shows the number of patients and percentage of Top 10 most frequently diagnoses and cancer diagnoses in patients receiving palliative care from services participating in PCOC in 2022. Cancer was the most frequently diagnosis and lung cancer was the most frequently cancer diagnosis for patient recorded in PCOC.

Figure 1.2: The interactive data visualisation shows the number of episodes and percentage of referral source of episodes by palliative care setting in 2022. Public hospitals accounted for the largest number of referrals both in inpatient and community settings. The second largest number of referrals for inpatient settings was community palliative care services, and for community settings was general practitioners.

Figure 1.3: The interactive data visualisation shows the number of episodes and percentage of elapsed days of closed episodes by palliative care setting in 2022. Most of episodes ended within 30 days both in inpatient and community settings. In general, inpatient episodes were shorter in duration than community episodes.

Figure 1.4: The interactive visualisation shows the number of phases and percentage of each type of phases by palliative care setting in 2022. Deteriorating and stable phases were more common in community settings than in inpatient settings, while terminal and unstable phases were more common in inpatient settings than in community settings.

Palliative care outcome measures

Key measures of quality care are the outcomes that patients, their families, and carers achieve. PCOC is a national program that uses standardised validated clinical assessment tools to benchmark and measure outcomes.

In 2009, PCOC and its participating services developed and implemented a set of national outcome measures and associated benchmarks. The PCOC benchmarks are aspirational and reflect good practice (for example, as achieved by the top 20% of services). The purpose of benchmarking is to drive palliative care service innovation and provide participating services with the opportunity to compare their service to other services from across the country.

The PCOC outcome measures cover:

- Time from date ready for care to episode start – it is intended to assess whether patients received timely palliative care in response to their need. It is calculated in days between the date the patient is ready to receive palliative care to the date that the palliative care episode starts.

- Time in the unstable phase – it is intended to assess whether there was a timely resolution of unstable palliative care phase. It is calculated as the difference between the unstable phase start date and end date.

- Change in symptoms/problems – it is intended to provide information about the responsiveness and appropriateness of the care plan in place and therefore the care provided. It is calculated by the difference in assessment from the beginning of a phase to the end of phase and is calculated using the measures from both the Palliative Care Problem Severity Score (PCPSS) and PCOC Symptom Assessment Scale (PCOC SAS).

A full description of each of the PCOC outcome measures and benchmarks reported here is included in the PCOC Guide to National Outcome Measures and Benchmarks and Data sources section. Table PCOC.9 also presents each benchmark, along with the proportion of palliative care episodes/phases meeting the outcome for each benchmark by palliative care setting; also see Figures PCOC.2 and 4.

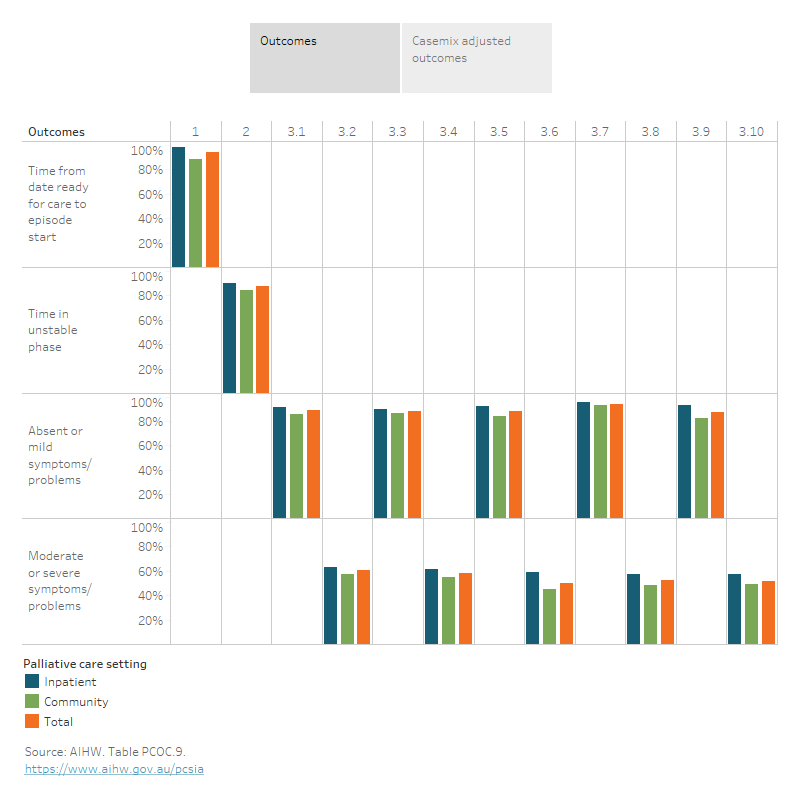

In 2022, the data on 79,500 palliative care episodes and 176,300 palliative care phases recorded in PCOC revealed the following key findings on palliative care outcomes (Figure PCOC.2 and Table PCOC.9):

- Over 9 in 10 (94%) episodes commenced on the day the patient was ready for palliative care or the day following – 98% in inpatient settings and 88% in community settings.

- Almost 9 in 10 (87%) unstable phases lasted for 3 days or less – 90% in inpatient settings and 84% in community settings.

- Almost 9 in 10 palliative care phases that started with absent/mild symptom/problem remained absent/mild at the end of the palliative care phase – 89% for pain severity and 88% each for distress related to pain, fatigue, or family/carer problems. For distress related to breathing problems a higher proportion remained in the absent/mild phase (94%).

- The proportion of phases resolved in the absent/mild symptom outcome range was less likely when the patient had moderate/severe symptoms to begin with, especially for those with fatigue, breathing problems and family/care problems:

- 3 in 5 palliative care phases that began with moderate or severe patient pain was reduced to absent/mild by the end of the palliative care phase – 61% for pain severity and 58% for distress from pain.

- 1 in 2 palliative care phases starting with moderate or severe distress from fatigue, breathing problems or family/care problems was reduced to absent/mild at the end of the palliative care phase – 50% for fatigue, 53% for breathing problems and 52% for family/care problem.

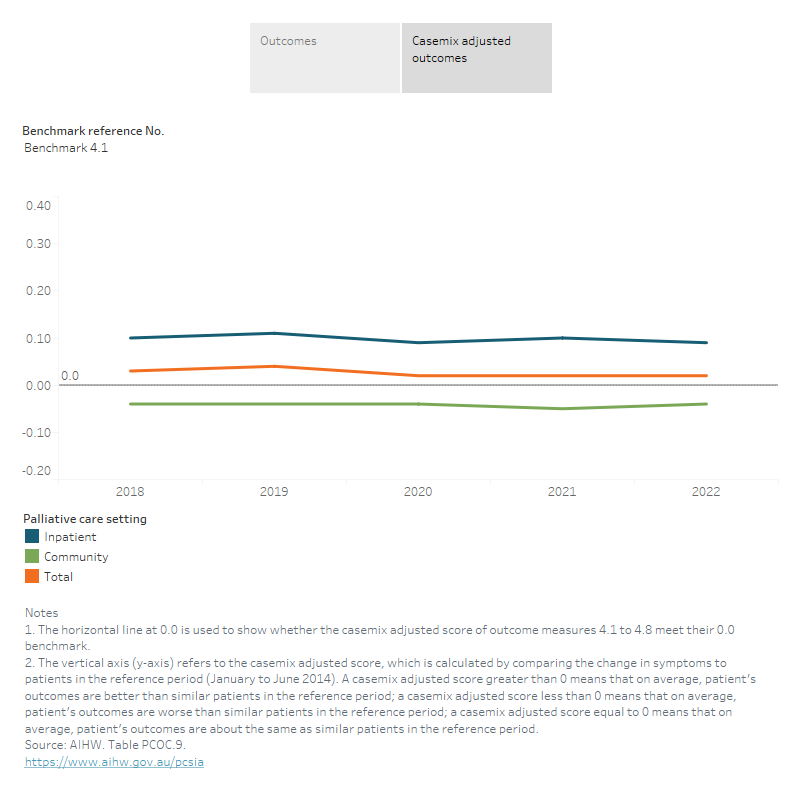

Casemix adjusted outcomes measure the change in symptoms relative to the national average, it allows services to compare the change in symptom and problem scores for ‘like’ patients (patients in the same phase who started with the same level of symptoms). It is calculated by measuring the mean change in symptoms on both the Palliative Care Problem Severity Score (PCPSS) and PCOC Symptom Assessment Scale (PCOC SAS), after adjusting for both phase and the symptom score at the start of each phase.

The casemix adjusted outcomes include a suite of eight casemix adjusted scores, which are calculated by comparing the change in symptoms to patients in the reference period (January to June 2014). If a casemix adjusted score is

- greater than 0 – it means that on average, patient's outcomes are better than similar patients in the reference period

- less than 0 – it means that on average, patient's outcomes are worse than similar patients in the reference period

- equal to 0 – it means that on average, patient's outcomes are about the same as similar patients in the reference period.

A full description of each of the casemix adjusted outcome measures and benchmarks reported here is included in the PCOC Guide to National Outcome Measures and Benchmarks and Data sources section.

In 2022, the casemix adjusted score was greater than 0 for all 8 outcome measures across all settings and in inpatient settings, indicating an improvement in patient’s outcomes to the reference period. However, in community settings there were 3 outcome measures with a score slightly less than 0 – pain severity, distress from pain and nausea – indicating that outcomes had not improved to the reference period (Figure PCOC.2).

Figure PCOC.2: Palliative care outcome results, 2022

Figure 2.1: The interactive visualisation shows the outcomes of the PCOC benchmarks by palliative care setting in 2022. The benchmarks have been grouped in four categories including time from date ready for care to episode start (benchmark 1 – 94%), time in unstable phase (benchmark 2 – 87%), absent or mild symptoms/problems (benchmarks 3.1, 3.3, 3.5, 3.7, and 3.9 – 94% for benchmark 3.7, and 88–89% for other benchmarks), and moderate or severe symptoms/problems (benchmarks 3.2, 3.4, 3.6, 3.8 and 3.10 – ranging from 50% to 61%).

Figure 2.2: The interactive visualisation shows the casemix adjusted outcomes of the PCOC benchmarks by palliative care setting in 2022. The benchmarks have been grouped in two categories including clinician reported problem severity (benchmark 4.1–4.4) and patient reported symptom distress (benchmarks 4.5–4.8). In 2022, the casemix adjusted score was greater than 0 for all 8 outcome measures across all settings and in inpatient settings. However, in community settings there were 3 outcome measures with a score slightly less than 0 – benchmark 4.1, 4.5 and 4.6.

Trends

Services, patients and episodes of care

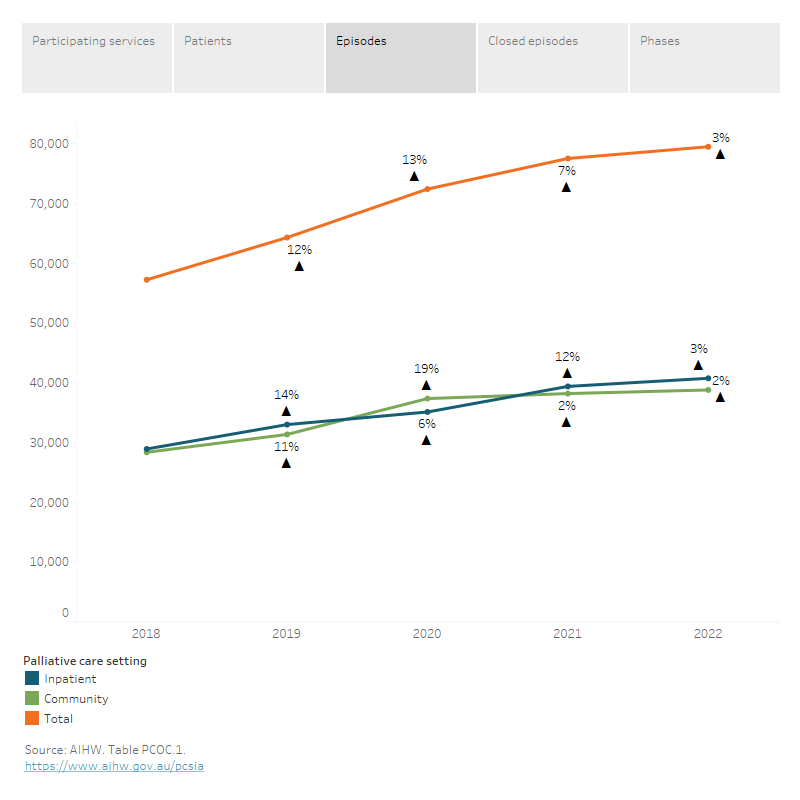

Between 2018 and 2022, the number of services participating in PCOC increased each year, from 133 to 180 services or a 35% increase over this period. The rate of increase was steeper between 2018 and 2020 (11% increase from 2018 to 2019 and 15% increase from 2019 to 2020), and then slowed considerably between 2020 and 2022 (4.1% increase from 2020 to 2021 and 1.7% increase from 2021 to 2022).

This pattern was also observed for palliative care episodes over the same period – episodes increased by 12–13% between 2018 and 2020 and slowed to 7.1% and 2.5% increase in the next 2 years to 2022. However, this trend differed somewhat by palliative care setting. For inpatient palliative care episodes, the increase was steeper from 2018 to 2019 (14%) and 2020 to 2021 (12%) than other years (6.4% increase from 2019 to 2020 and 3.5% from 2021 to 2022). While, for community-based episodes, the increase was steepest (19%) between 2019 and 2020 and then slowed considerably in the 2 years to 2022 (2.2% and 1.6%, respectively).

Interestingly, the number of patients steadily increased each year between 2018 and 2021 (10–13% annual increase), before slowing to 4% increase in the 12 months to 2022 (Figure PCOC.3).

Figure PCOC.3: Trends in number of palliative care services, patients, episodes of care and phases for services participating in PCOC, 2018 to 2022

Figure 3.1: This line graph shows the trend of number of services participating in PCOC from 2018 to 2022. The number of services increased every year over this period; however, the rate of increase was steeper between 2018 and 2020 (11–15% annual increase), and then slowed considerably between 2020 and 2022 (2–4% annual increase).

Figure 3.2: This line graph shows the trend of number of patients receiving palliative care from services participating in PCOC from 2018 to 2022. The number of patients steadily increased each year between 2018 and 2021 (10–13% annual increase), before slowing to 4% increase in the 12 months to 2022.

Figure 3.3: This line graph shows the trend of number of episodes for patients receiving palliative care from services participating in PCOC by palliative care setting from 2018 to 2022. The number of episodes increased every year in this period; however, the rate of increase was steeper between 2018 and 2020 and slowed considerably between 2020 and 2022.

Figure 3.4: This line graph shows the trend of number closed episodes for patients receiving palliative care from services participating in PCOC by palliative care setting from 2018 to 2022. The number of closed episodes increased every year in this period; however, the rate of increase was steeper between 2018 and 2020 and then began to slow between 2020 and 2022.

Figure 3.5: This line graph shows the trend of number of phases for patients receiving palliative care from services participating in PCOC by palliative care setting from 2018 to 2022. The number of phases increased every year in this period; however, the rate of increase was steeper between 2018 and 2020 and then began to slow between 2020 and 2022.

Palliative care outcome measures

Of particular interest is whether there have been changes in the proportion of patients achieving a positive outcome. Between 2018 and 2022, most outcome measures have remained relatively stable. However, there have been some measures where more notable movements have been observed over this time period (Figure PCOC.4):

- notable drop in 2021 in those assessed as ready for care and receiving it within 2 days (86% in 2021 compared with relatively stable proportions of around 93–94% for all other years (between 2018 and 2020, and 2022; benchmark 1). Note that this drop occurred at a time where there were restrictions and subsequent pressures on the health care system due to COVID-19 pandemic which may have impacted on how people were accessing and receiving palliative care services, and their outcomes during this period.

- slight increase in those remaining with absent/mild distress from fatigue at the end of the palliative care phase (from 85% to 88%; benchmark 3.5)

- increase in those moving from moderate/severe to absent/mild symptoms at the end of the phase for distress from fatigue (from 44% to 50%; benchmark 3.6) and for breathing problems (from 46% to 53%; benchmark 3.8).

Note that comparisons of outcome measures over time should be interpreted with caution, as these outcomes measures may be affected by compositional changes in the population, given that the number of services participating in PCOC is changing.

Figure PCOC.4: Trends in palliative care outcome results, 2018–2022

Figure 4.1: This interactive visualisation shows the trend of outcomes of the PCOC benchmarks by palliative care setting between 2018 and 2022. Between 2018 and 2022, most outcome measures have remained relatively stable. However, there have been some measures where more notable movements have been observed over this period, including benchmark 1, benchmark 3.5, 3.6 and 3.8.

Figure 4.2: This interactive visualisation shows the trend of casemix adjusted outcomes of the PCOC benchmarks by palliative care setting between 2018 and 2022. Between 2018 and 2022, the casemix adjusted score was greater than 0 for all 8 outcome measures across all settings and in inpatient settings. However, in community settings there were 3 outcome measures with a score slightly less than 0 – benchmark 4.1, 4.5 and 4.6.

Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration

The Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC) is a national program using standardised validated clinical assessment tools to measure and benchmark patient outcomes in palliative care.

Participation in the PCOC is voluntary and open to all palliative care service providers across Australia. Representation is sought from public and private health sectors, rural and metropolitan areas, and inpatient and community settings. PCOC aims to assist services to improve the quality of the palliative care they provide through the analysis and benchmarking of patient outcomes. The PCOC model is embedded into routine clinical practice. As such, the standardised clinical assessment tools are used as part of routine practice with each consecutively admitted patient.

The PCOC palliative care outcomes collection dataset (PCOC 2012) includes data on patient demographics, clinical setting information, and patient outcomes from the following PCOC assessment tools (Daveson et al. 2021; PCOC 2012):

- Palliative Care Phase

- PCOC Symptom Assessment Scale (PCOC SAS)

- Palliative Care Problem Severity Score (PCPSS)

- Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) Scale

- Resource Utilisation Groups – Activities of Daily Living (RUG-ADL).

Data using Version 1 of PCOC dataset were collected between January 2006 and January 2007. Version 2 of the dataset was enacted from July 2007, and Version 3 was implemented in July 2012 (PCOC 2012). More information about this dataset can be found in PCOC Version 3.0 Dataset Data Dictionary and Technical Guidelines under PCOC Research & data Palliative care outcomes collection.

The national information presented in this report reflect all palliative care services that submitted data for the 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022 period. A full list of the services that contributed data to this report can be found on the Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration website.

Outcome measures and benchmarks

In 2009, PCOC and participating services, developed and implemented a set of national outcome measures and associated benchmarks to drive service innovation and allow participating services to compare their service nationally. The most recent update was released in 2015, which included the addition of 6 measures to Benchmark 3 relating to fatigue, breathing problems and family/carer problems. More information can be found on the PCOC Research & data webpage.

Further detail on the definition and measurement of each outcome measure and associated benchmark are provided in the following.

Outcome measure 1: Time from date ready for care to episode start

Measures the time (in days) between the date the patient is ready to receive care and the actual start date of the episode of palliative care by the service. This is measured for all episodes of care and across all settings of care.

To meet Benchmark 1, 90% of episodes of care must commence on the day of, or the day following, the date ready for care.

This measure replaced ‘Time from referral to first contact for the episode’ in July 2013 in consultation with participating services.

Outcome measure 2: Time in unstable phase

Measures the number of days the patient spent in an unstable phase. An unstable phase alerts clinical staff to the need for urgent or emergency intervention requiring an associated change in the existing care plan. Once assigned, and with the new care plan in place, the clinical team monitor for improvements in the patient and/or family/carer condition. Improvement can be demonstrated through observation and clinical assessments (reducing symptom distress and problem severity scores). With signs of improvement, the new care plan demonstrates its effectiveness and thus, the patient/family/carer can be moved out of the unstable phase into another relevant phase. However, at any time a patient is identified as dying within days (clinical indicators), the phase is immediately changed to terminal phase.

For services to meet Benchmark 2, 90% of unstable phases must last for 3 days or less.

Outcome measure 3: Change in symptoms/problems

Symptoms and problems for Benchmark 3 include the items of pain severity, distress related to pain, distress caused by fatigue, distress caused by breathing problems, and family/carer problems.

Symptoms and problems are measured at the start and end of a phase, and although symptoms and problems can be measured throughout the phase, an outcome is defined as the change from the beginning and at the end of the phase. It follows that phase records must have valid start and end scores to be included.

Two of the five PCOC clinical assessment tools are used to measure these patient and family symptoms and problems: the patient-rated PCOC Symptom Assessment Scale (PCOC SAS) and the clinician-rated Palliative Care Problem Severity Score (PCPSS).

A positive outcome for a patient is to have the symptom/problem in the absent to mild range at the end of a phase (for example, when the type of phase changes or the person is discharged from the service).

There are 2 benchmarks for each symptom/problem. The first benchmark is that at least 90% of phases that start with patients experiencing absent/mild symptoms (or problems) remain absent/mild at the end of the phase. This is reflective of anticipatory care. The second benchmark is that at least 60% of phases that start with patients experiencing moderate/severe symptoms (or problems) reduce to an absent/mild level by the end of the phase. This is reflective of responsive care.

Outcome measures 3.1–3.4: Pain

Pain management is acknowledged as ‘core business’ of palliative care services; hence, measuring patient pain is considered to be a vitally important outcome for palliative care services. The PCPSS measures pain severity rated by the clinician, used in Benchmarks 3.1 and 3.2, and the PCOC SAS measures patient-rated distress from pain, used in Benchmarks 3.3 and 3.4.

Outcome measure 3.5–3.6: Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common symptom in palliative care patients who have advanced cancer or other serious and/or life-threatening illnesses. The PCOC SAS is used for Benchmarks 3.5 and 3.6.

Outcome measure 3.7–3.8: Breathing problems

Breathing problems is a common symptom reported by patients receiving palliative care. The PCOC SAS is used to measure patient distress related to this symptom. This is used for Benchmarks 3.7 and 3.8.

Outcome measure 3.9–3.10: Family/carer problems

The PCPSS family/carer domain measures problems associated with a patient’s condition or palliative care needs. The clinician reports on the severity of the problems of their family/carer. This is used for Benchmarks 3.9 and 3.10.

Outcome measure 4: Change in symptoms relative to the national average (X-CAS)

Change in symptoms relative to the national average measures the mean change in symptoms on the PCPSS/PCOC SAS that are adjusted for both phase and for the symptom score at the start of each phase. This measure allows services to compare the change in symptom score for ‘like’ patients, for example, patients in the same phase who started with the same level of symptom. Eight symptoms are included in the measure:

- PCPSS pain, other symptoms, psychological/spiritual, family/carer; and

- PCOC SAS pain, nausea, bowel problems, breathing problems.

The measure is referred to as the X-CAS, with X representing the fact that multiple symptoms are included, and CAS is an abbreviation for Casemix Adjusted Score.

A positive score indicates that a service is performing above the baseline national average and a negative score that it is below the baseline national average.

The baseline national average has been calculated based on the period January to June 2014. Each service is measured against this baseline national average for each 6-month reporting period. This allows each service to measure any change in their symptom management over time.

For further details on each of the PCOC outcome measures and benchmarks, refer to PCOC Guide to National Outcome Measures and Benchmarks.

| Key concept | Description |

|---|---|

Anticipatory care | Anticipatory care is care that anticipates the needs of the patient and carer in order to avoid an increase in the problem or need. The PCOC anticipatory care benchmarks relate to patients who have absent or mild symptoms/problems at the start of a phase of palliative care. To meet this benchmark, 90% of these phases must end with absent or mild symptom/problem scores. |

Benchmark | A predefined level of achievement. In PCOC, the outcomes of groups of palliative care patients (e.g., within a service/state /nationally) are aggregated and compared to this level. The PCOC benchmarks are aspirational and reflect good practice (top 20%). The PCOC benchmarks are the same regardless of sector (public/private), location or role. |

Casemix adjusted outcome measure | This measures the mean change in symptoms, after adjusting for both phase and the symptom score at the start of each phase. This measure allows comparison of change in symptom and problem scores for ‘like’ patients. A positive score indicates that a service is achieving above the baseline national average and a negative score indicates that it is below the baseline national average. PCOC currently reports on 8 case-mix adjusted outcomes: Distress regarding pain, bowel problems, nausea, and breathing problems; and symptom severity regarding pain, other symptoms, psychological/spiritual problems, and family/carer problems. |

Closed palliative care episode | A closed palliative care episode is one that includes an episode end date within the specified reporting period. An episode ends or is closed when the following occurs: setting of palliative care changes (for example community to inpatient); principal clinical intent of the care changes and the patient is no longer receiving palliative care; the patient is formally separated from the service; or the patient dies. |

Community episode | Episodes where the patient received specialist palliative care in a community setting, often deemed as the patient’s ‘home’. This may be in their private residence, an aged care, mental health, or disability residential facility or in a correctional facility. |

Elapsed days | The number of days between the start and end of an episode. This does not include leave days. Within the community setting, elapsed days do not reflect the number of times the palliative care team visited the patient. |

Inpatient episode | Inpatient episodes of care are those for which the intent of the admission was for the patient to be in a hospital or hospice overnight. This includes those patients who were admitted and died on the same day. |

Median | The midpoint of a list of observations that have been ranked from the smallest to the largest. |

Outcome measure | In PCOC, an outcome measure is both a measure used to assess change in response to an intervention (e.g., palliative care), and is also used to refer to a standardised assessment tool or methodology designed to measure clinical concepts. The PCOC outcome measures cover: time from the date the patient is ready for palliative care to palliative care episode start date (timeliness of palliative care); time that the patient spent in an unstable phase (responsiveness to urgent needs); change in patient symptoms and problems (responsiveness and appropriateness of the care plan in place). |

Palliative care episode

| A palliative care episode is a period of contact between a patient and a service where palliative care is provided in a single setting (for example, inpatient setting). A palliative care episode starts on the date a comprehensive palliative care assessment is undertaken and documented. An episode ends when one of the following occurs: setting of palliative care changes (for example community to inpatient); principal clinical intent of the care changes and the patient is no longer receiving palliative care; patient is formally separated from the service; or the patient dies. Palliative care episodes, as used in this report, include both open episodes (those without an episode end date in the reporting period), and closed episodes (see ‘closed episodes’). |

Palliative care patient | A person for whom a palliative care service accepts responsibility for assessment and/or treatment as evidenced by the existence of a medical record. Family and carers are included in this definition if interventions relating to them are recorded in the patient medical record. |

Daveson BA, Allingham SF, Clapham S, Johnson CE, Currow DC, Yates P, et al (2021) 'The PCOC Symptom Assessment Scale (SAS): A valid measure for daily use at point of care and in palliative care programs', PLOS ONE, 16(3): e0247250.

Masso M, Allingham SF, Banfield M, Johnson CE, Pidgeon T, Yates P et al (2015) ‘Palliative Care Phase: inter-rater reliability and acceptability in a national study’, Palliative Medicine, 29(1): 22–30.

PCOC (Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration) (2012) PCOC Version 3.0 Dataset Data Dictionary and Technical Guidelines. Wollongong: University of Wollongong.

PCOC (2021a) Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration Clinical Manual, University of Wollongong website, accessed 24 June 2023.

PCOC (2021b) PCOC Research and Data, University of Wollongong website, accessed 9 July 2023.