Palliative care workforce

In 2021, 289 full-time equivalent (FTE) palliative medicine physicians and 3,080 FTE palliative care nurses were employed in Australia. This section provides information on the number and characteristics of the employed workforce of physicians with a primary specialty of palliative medicine (referred to as ‘palliative medicine physicians’) and nurses working in palliative care (referred to as ‘palliative care nurses’).

This information was sourced from the National Health Workforce Dataset (NHWDS) for the period 2013 to 2021. It only includes information on medical practitioners and nurses, as these professionals can be specifically identified as palliative care providers using the Department of Health and Aged Care’s Health Workforce Data Tool (HWDT).

The palliative care workforce is made up of a broad range of professional groups, each playing a unique role in supporting people with a life limiting illness to receive comprehensive, patient-centred care. It is recognised that general practitioners, other medical specialists, social workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and other allied health professionals form an integral part of the palliative care workforce. However, existing national data sources are not able to accurately capture the extent of palliative care services provided by these health professionals. See Data sources for further details.

The information in this section was last updated in November 2023.

Workforce planning is an essential element in achieving functional and sustainable healthcare across the palliative care sector (DoH 2019). Understanding the size, demographics and distribution of the palliative care workforce is key to meeting the increasing demand for palliative care and will assist in identifying current need gaps and aid future planning.

In Australia, both doctors and nurses usually complete specialised training in addition to their medical/nursing degrees to work in palliative care.

Medical specialists must have completed post-graduate specialist training to become a palliative medicine physician. Palliative medicine physicians are required to have completed 3 years of full-time equivalent training in either a paediatric or adult setting under the supervision of a palliative medicine physician. Successful trainees gain the qualification of Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (FRACP) / Fellowship of the Australasian Chapter of Palliative Medicine (FAChPM) and are accredited to practice as a palliative medicine physician in Australia or New Zealand. Medical practitioners may also complete a 6-month Clinical Diploma in Palliative Medicine, but this qualification does not result in specialist accreditation (RACP 2020).

The classification of nurses in Australia varies with the type of training that has been undertaken (for more information see the Department of Health and Aged Care website). Nurse practitioners, registered nurses and enrolled nurses need to complete a variety of short or more comprehensive courses (including postgraduate certificates and Master’s degrees) to work in the field of palliative care, and postgraduate qualifications are generally required for nurses working in specialist palliative care services (Centre for Palliative Care 2021).

While data on nurse practitioners are included in National Health Workforce Dataset and have been reported in Factsheets for Nursing and Midwifery, nurse practitioners are not identified in the Health Workforce Data Tool and are therefore not included in this section. Further, in the Health Workforce Data Tool nurses and midwives are grouped together under professions, hence the comparison of palliative care nurses is to all nurses and midwives in this section.

Note, the standard full-time working week (1 full-time equivalent, FTE) for medical practitioners is defined as 40 hours, while it is 38 hours for all other professions, including nurses.

Key points

In 2021:

- there were 289 full-time equivalent palliative medicine physicians (1.1 per 100,000 population) and 3,080 full-time equivalent palliative care nurses (12 per 100,000 population)

- women accounted for 2 in 3 (64%) employed palliative medicine physicians and 9 in 10 (92%) employed palliative care nurses

- most worked in Major cities – over 4 in 5 (84%) employed palliative medicine physicians and almost 3 in 4 (72%) employed palliative care nurses

- 3 in 4 (73%) employed palliative medicine physicians worked in a hospital setting, compared with over half (52%) for employed palliative care nurses.

Between 2013 and 2021:

- the number of employed palliative medicine physicians increased by 70% (from 183 to 311) – steeper than that observed for all employed specialist medical practitioners (36% increase, or from 29,200 to 39,700)

- for employed palliative care nurses, the number increased by 16% (from 3,265 to 3,798) between 2013 and 2020, and then decreased by 7.4% to 3,518 in 2021. While the number of all employed nurses and midwives increased each year by 24% (from 295,100 to 366,700) over the same period.

Characteristics of specialist palliative care workforce

In 2021, there were 311 palliative medicine physicians (289 FTE) and 3,518 palliative care nurses (3,080 FTE) employed in Australia, accounting for 0.8% of all employed specialist medical practitioners and 1.0% of all employed nurses and midwives.

In 2021, among employed palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses (Figure Wk.1):

- Almost 2 in 3 (64%) palliative medicine physicians were women – almost twice as high as for all employed specialist medical practitioners (36%; Table Wk.7). Female palliative care physicians were younger than their male counterparts (76% and 65% were aged under 55, respectively).

- Almost 9 in 10 (92%) palliative care nurses were women – slightly higher than the proportion among all employed nurses and midwives (88%; Table Wk.8). Female palliative care nurses were older than their male counterparts (32% and 22% were aged 55 and over, respectively).

- The rate of palliative medicine physicians (FTE per 100,000 population) ranged from 0.8 in South Australia to 1.4 in New South Wales (data are not presented for Australian Capital Territory and North Territory due to small numbers). For palliative care nurses, the rate ranged from 10.4 in Queensland to 15.8 in Northern Territory.

- More than half of palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses worked in a hospital setting (73% and 52%, respectively) and most were principally employed as a clinician (93% for palliative medicine physicians and 95% for palliative care nurses, respectively).

- Of the 3,518 palliative care nurses, over 4 in 5 (83% or 2,925) were registered nurses (only) and 15% (509) were enrolled nurses (only), see Table Wk.1.

Further, 97 nurse practitioners worked in palliative care with 80 of those employed as a nurse practitioner in 2021 (see Factsheets on Nursing and Midwifery for further details).

In addition, according to data from the Medical Board of Australia Registrant, there were 6 paediatric palliative medicine physicians in Australia over the period 01 October 2021 to 31 December 2021, accounting for 0.2% of all physicians with a primary speciality of paediatrics and child health (3,556) over this period (MBA 2021).

Figure WK.1: Characteristics of employed palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses, 2021

Figure 1.1: This interactive visualisation shows the number and percent of employed palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by sex and age group in 2021. Physicians aged 35–44 accounted for the largest proportion of palliative medicine physicians both for males and females (with publishable data). For palliative care nurses, male nurses aged 35–54 accounted for the largest proportion and female nurses aged 45–64 accounted for the largest proportion.

Figure 1.2: This interactive visualisation shows the number of employees, number of FTE employee, FTE per 100,000 population, number of clinical FTE employees and clinical FTE per 100,00 population of palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by states and territories in 2021. New South Wales had the highest number of palliative medicine physicians, while Victoria had the highest number of palliative care nurses.

Figure 1.3: This interactive visualisation shows the number of employees, number of FTE employee, FTE per 100,000 population, number of clinical FTE employees and clinical FTE per 100,00 population of palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by principal role in 2021. Clinician was the most common principal role of the job for both palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses.

Figure 1.4: This interactive visualisation shows the number of employees, number of FTE employee, FTE per 100,000 population, number of clinical FTE employees and clinical FTE per 100,00 population of palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by work setting in 2021. Hospital was the most common work setting for both palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses.

Hours worked

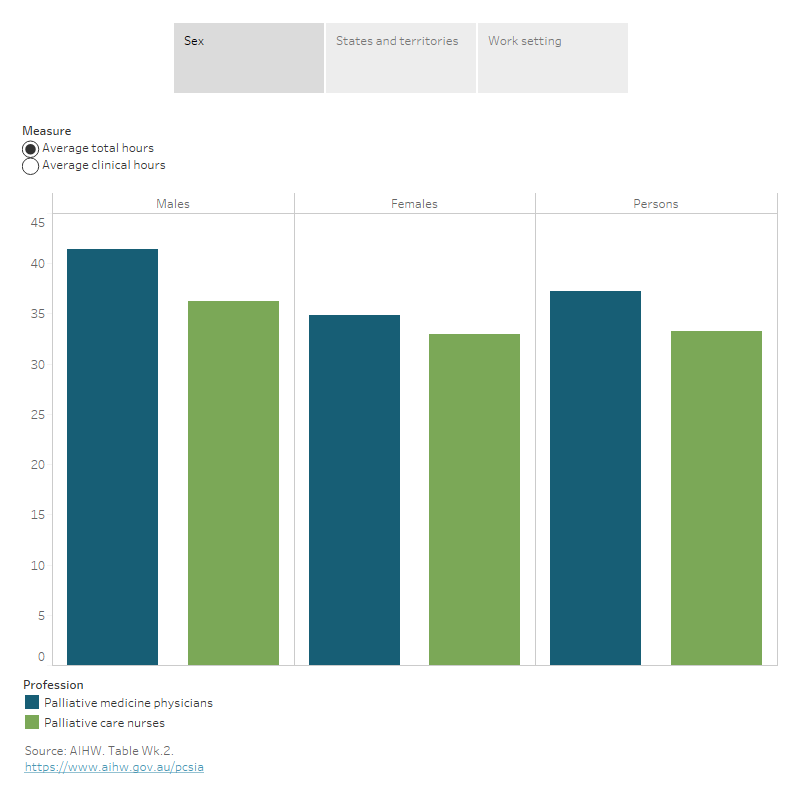

In 2021, among employed palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses (Figure Wk.2):

- Palliative medicine physicians worked an average of 37 total hours per week (30 clinical hours), which was less than the average weekly hours for all employed specialist medical practitioners (42 total hours and 35 clinical hours, respectively).

- Palliative care nurses worked an average of 33 total hours per week (31 clinical hours), similar to that worked by all employed nurses and midwives (34 total hours and 30 clinical hours, respectively).

- Men worked longer hours on average per week than women both for palliative medicine physicians (41 compared with 35 total hours) and palliative care nurses (36 compared with 33 total hours). This is consistent with the pattern observed for all employed specialist medical practitioners and all employed nurses and midwives.

- For palliative medicine physicians, the average hours worked per week varied by states and territories, ranging from 31 total hours in South Australia to 42 total hours in Queensland (note data are not presented for Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory due to small counts).

- For palliative care nurses, the average hours worked per week ranged from 31 total hours in Tasmania to 35 total hours in New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory.

- The average hours worked per week for palliative medicine physicians ranged from 32–38 hours and for palliative care nurses from 30–34 hours across most work settings. However, palliative medicine physician working primarily in private practice tended to work longer hours, while palliative care nurses worked fewer hours. Note that the average hours worked per week for private practice was based on small counts – 12 for palliative medicine physicians and 8 for palliative care nurses.

Over 4 in 5 (84%) employed palliative medicine physicians and almost 3 in 4 (72%) employed palliative care nurses worked mainly in Major cities. There was a higher proportion of palliative care nurses working in regional areas (Inner regional and Outer regional combined) than palliative medicine physicians (28% compared with 16%; Table Wk.4).

Taking into account differences in population sizes for each remoteness area, the FTE per 100,000 population for palliative medicine physicians was 1.3 in Major cities, declining to 0.8 in Inner regional and 0.5 in Outer regional areas, respectively. For palliative care nurses, the FTE per 100,000 was relatively similar across Major cities and regional areas – ranging from 10.3 FTE in Outer regional areas to 13.1 FTE in Inner regional areas – but then declined to 5.5 FTE in Remote and Very remote areas (combined).

The average total hours worked per week for palliative medicine physicians increased with increasing remoteness, from 37 hours in Major cities to 40 hours in Outer regional areas. While for palliative care nurses, the average hours worked per week was similar for Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas (around 33 hours), but then increased to 37 hours for those in Remote and Very remote areas (combined).

Note that for palliative medicine physicians, data are not presented for Remote and Very remote areas due to small counts.

Figure Wk.2: Average hours worked per week by employed palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses, 2021

Figure 2.1: This interactive visualisation shows average total hours and average clinical hours for palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by sex in 2021. Palliative medicine physicians had longer average total hours than palliative care nurses, while palliative care nurses had longer average clinical hours than palliative medicine physicians for both males and females.

Figure 2.2: This interactive visualisation shows average total hours and average clinical hours for palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by states and territories in 2021. Palliative medicine physicians in Queensland had the longest average total hours, and palliative care nurses in New South Wales had the longest average total hours out of all states and territories.

Figure 2.3: This interactive visualisation shows average total hours and average clinical hours for palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by work setting in 2021. Palliative medicine physicians in tertiary educational facilities had the longest average total hours, and palliative care nurses in outpatient services had the longest average total hours.

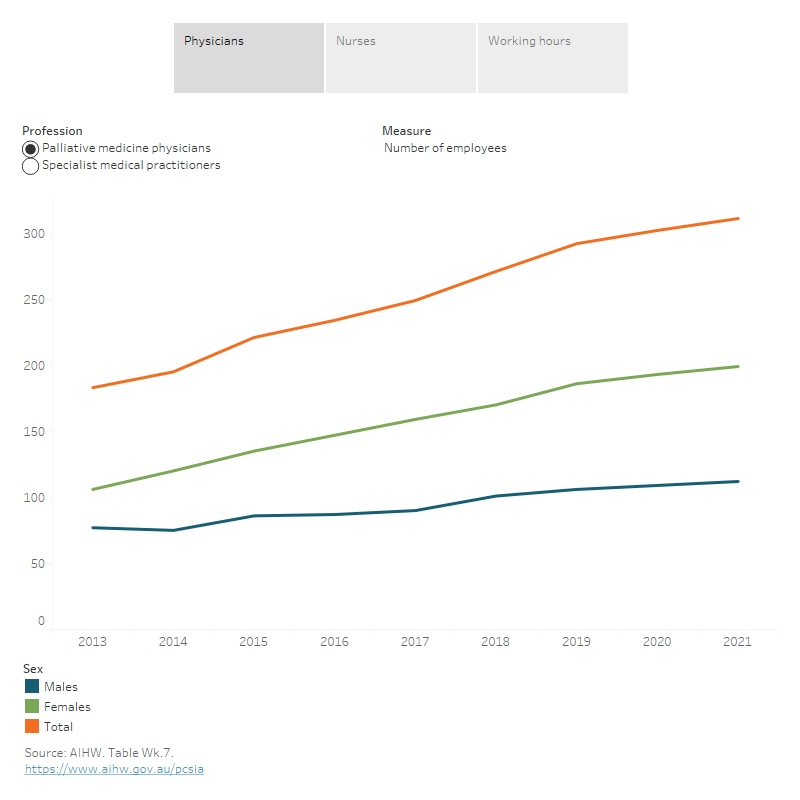

Trends

Between 2013 and 2021, the number of employed palliative medicine physicians increased each year from 183 to 311 (70% increase) – a steeper increase than that observed for all employed specialist medical practitioners (36% increase over this period). The growth in physicians was steeper for females than males for both palliative medicine physicians (88% vs 45%) and all specialist medical practitioners (73% vs 21%). After accounting for population size, the FTE rate for palliative medicine physicians and specialist medical practitioners also increased slightly between 2013 and 2021– for palliative medicine physicians from 0.8 to 1.1 FTE per 100,000 population, and for specialist medical practitioners from 139 to 161 FTE per 100,000 population (Figure Wk.3).

The number of employed palliative care nurses generally increased each year to 2020 – from 3,265 to 3,798 or 16% increase between 2013 and 2020. It then declined by 7.4% in the 12 months to 3,518 in 2021. Over the same period, the number of all employed nurses and midwives increased each year by 24% (from 295,100 to 366,700). When taking into account the size of the population a slightly different pattern emerged – for palliative care nurses the FTE rate per 100,000 population remained relatively stable between 2013 and 2018 (12.0–12.2 FTE), it then increased in 2019 (to 12.5 FTE) and in 2020 (to 12.8 FTE), before declining again to 12.0 FTE in 2021. While for all nurses and midwives the FTE rate per 100,000 population increased slightly each year from 1,155 to 1,274 FTE between 2013 and 2021 (Figure Wk.3).

The average number of total hours worked per week has declined slightly for palliative medicine physicians – from 39 hours (in 2013–2016) to 38 hours (in 2017–2018) to 37 hours in 2019–2021. While for palliative care nurses the average hours worked has remained relatively stable (around 33 hours) over the same period (Figure Wk.3). Both showed an increase in total hours worked per week for 2021 compared to 2020, with palliative medicine physicians increasing by 0.3 hours (36.9 to 37.2) and palliative care nurses by 0.5 hours (32.8 to 33.3).

Figure Wk.3: Trends in employed palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses, 2013–2021

Figure 3.1: This interactive visualisation shows the trend of number of employees, number of FTE employee, FTE per 100,000 population, number of clinical FTE employees and clinical FTE per 100,00 population for palliative medicine physicians and all specialist medical practitioners by sex between 2013 and 2021. The number of both professions trended upwards from 2013 to 2021.

Figure 3.2: This interactive visualisation shows the trend of number of employees, number of FTE employee, FTE per 100,000 population, number of clinical FTE employees and clinical FTE per 100,00 population for palliative care nurses and all nurses and midwives by sex between 2013 and 2021. The number of employed palliative care nurses generally increased each year to 2020, and then declined from 2020 to 2021; meanwhile, the number of all nurses and midwives trended upwards from 2013 to 2021.

Figure 3.3: This interactive visualisation shows the trend of average total hours and average clinical hours for palliative medicine physicians and palliative care nurses by sex between 2013 and 2021. The average total hours worked per week had declined slightly for palliative medicine physicians, while for palliative care nurses the average total hours worked per week had remained relatively stable between 2013 and 2021.

National Health Workforce Dataset

The Workforce Surveys are administered to all health practitioners registered by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) and are included as part of the registration renewal process. The workforce surveys are voluntary. The respective surveys are used to provide nationally consistent workforce estimates. They provide data not readily available from other sources, such as on the type of work done by, and job setting of, health practitioners; the number of hours worked in a clinical or non-clinical role, and in total; and the number of years worked in, and intended to remain in, the health workforce. The survey also provides information on those registered health practitioners who are not undertaking clinical work or who are not employed. The information from the workforce surveys, combined with some National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (NRAS) registration data items, comprises the National Health Workforce Dataset (NHWDS).

Past and present surveys have different collection and estimation methodologies, questionnaire designs and response rates. As a result, caution should be taken in comparing historical data from the AIHW Medical Labour Force Surveys prior to 2010 with data from the NHWDS.

Details of medical practitioners, nurses and allied health practitioners registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) are available for public access through the Department of Health and Aged Care’s Health Workforce Data Tool (HWDT). This report examines medical practitioners and nurses, as these professionals can be identified using the HWDT as specialist palliative care providers.

The palliative care workforce is made up of a broad range of professional groups, each playing a unique role in supporting people with a life limiting illness to receive comprehensive, patient-centred care. It is recognised that general practitioners, other medical specialists, social workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and other allied health professionals form an integral part of the palliative care workforce; however, existing national data sources are not able to accurately capture the extent of palliative care services provided by these health professionals.

The numbers in this report reflect those extracted using the HWDT as of 1 July 2023. Workforce for each profession is defined as those employed in Australia in the profession, who specialise in or work in palliative care. Additionally, an employed health professional is defined in this report as one who:

- reported (the week before the survey) practising in Australia (including practitioners on leave for less than 3 months), or

- was involved with work that is principally concerned with their health discipline (including non-clinical roles – for example education, research, and administration).

Employed palliative medicine physicians only include practitioners whose main speciality is palliative care. Employed palliative care nurses include only nurses whose principal job area is palliative care. This excludes those practitioners who:

- practice palliative care as a second or third speciality

- are registered in the profession but are retired from regular work

- work outside the profession

- work in the profession but are on extended leave of 3 months or more

- are only engaged in unpaid/volunteer work or

- work outside Australia.

The full-time equivalent (FTE) is defined in this report as the number of standard-hour workloads worked by employed health professionals. The FTE is calculated by multiplying the number of employed professionals in a specific category by the average total hours worked by employed people in that category and dividing by the number of hours in a standard working week. The standard working week, equivalent to 1 FTE, is based on working 38 hours per week for all practitioners with the exception of medical practitioners, where it is defined as 40 hours. In this report, the FTE for palliative care nurses is therefore based on working 38 hours per week and for palliative medicine physicians 40 hours per week.

There may be differences between the data presented here and that published elsewhere due to different calculation or estimation methodologies or extraction dates. Additionally, the HWDT uses a randomisation technique to confidentialise small numbers. This can result in differences between the column sum and total and small variations in numbers from one data extract to another.

Further information regarding the medical practitioner workforce and Nursing and midwifery workforce surveys is available from the Department of Health and Aged Care’s Health Workforce data website.

| Key concept | Description |

|---|---|

Total number of hours a practitioner spends working in the area of clinical practice; that is, the diagnosis, care and treatment, including recommended preventive action, of patients or clients. | |

Employed | An employed health professional is defined in this report as one who:

‘Employed’ people are referred to as the ‘workforce’ in this report. This includes only practitioners whose main speciality is palliative care and excludes those practitioners practising palliative care as a second or third speciality. It also excludes those who are registered in the profession but are retired from regular work, working outside the profession, working in the profession but on extended leave of 3 months or more, who are only engaged in unpaid/volunteer work or working outside Australia. |

Full-time equivalent | The number of standard-hour workloads worked by employed health professionals. The Full-time equivalent (FTE) is calculated by multiplying the number of employed professionals in a specific category by the average total hours worked by employed people in that category and dividing by the number of hours in a standard working week. The standard working week is assumed to be 38 hours, equivalent to 1 FTE, for all practitioners with the exception of medical practitioners where it is assumed to be 40 hours. |

The classification of nurses in Australia varies with the type of training they have undertaken. Nurse practitioners, registered nurses and enrolled nurses need to complete a variety of short or more comprehensive courses (including postgraduate certificates and Master’s degrees) to work in the field of palliative care, and postgraduate qualifications are generally required for nurses working in specialist palliative care services. | |

Palliative medicine physician | Palliative medicine physicians are required to have completed 3 years of full-time equivalent training in either a paediatric or adult setting under the supervision of a palliative medicine physician. Successful trainees gain the qualification of Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (FRACP) / Fellowship of the Australasian Chapter of Palliative Medicine (FAChPM) and are accredited to practice as a palliative medicine physician in Australia or New Zealand. |

Centre for Palliative Care (2021) Professional Development, Centre for Palliative Care website, accessed 22 June 2023.

DoH (Department of Health) (2019) The National Palliative Care Strategy 2018, DoH, Australian Government, accessed 20 June 2023.

MBA (Medical Board of Australia) (2021) Registrant data, Reporting period: 1 October 2021 to 31 December 2021, MBA website, accessed 20 June 2023.

RACP (Royal Australian College of Physicians) (2020) Training pathways, RACP website, accessed 22 June 2023.