Technical notes

Department of Defence personnel solution data

Information on ex-serving ADF members was obtained from the Personnel Management Key Solution (PMKeyS). PMKeyS is a Department of Defence staff and payroll management system that contains information on all people with ADF service on or after 1 January 2001 (when the system was introduced). The data supplied for this project included records for those who separated from the ADF between January 2001 and September 2020.

Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP)

The Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) is a partnership among Australian Government agencies to develop a secure and enduring approach for combining information on healthcare, education, government payments, personal income tax, and demographics (including the Census) to create a comprehensive picture of Australia over time (ABS 2018). More information about the MADIP can be found at Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au). The key MADIP data sets used in this analysis were:

- MADIP Person Linkage Spine (Australian Bureau of Statistics)

- Core demographic dataset (Australian Bureau of Statistics)

- 2016 Census of Housing and Population (Australian Bureau of Statistics)

Data linkage, also known as data integration, is a process that brings together information relating to an individual from more than one source. This report utilised deterministic and probabilistic linkage between two data sets: Defence-held Personnel Management Key Solution (PMKeyS) data and the 2016 Census of Population and Housing.

After undergoing data checking and cleaning, the PMKeyS data set was linked using a probabilistic data linkage to the AIHW/ABS interoperable spine. This spine allows data held by both organisations to be linked without the need for sharing any identifiable information. The data was linked to the spine by matching by name, sex and date of birth. The linkage procedure involved creating record pairs—one from each data set—by running a series of passes that allow for variation in full name information and demographic data. There were over 129,000 links found in the ABS/AIHW-interoperable spine linkage. This linkage was carried out by the Data Linkage Unit at the AIHW. Using unidentifiable PINs, shared between the AIHW and the ABS, this data set was then securely transferred to the ABS to be linked to the MADIP spine. ABS staff, using the ABS' data linkage environment were subsequently able to link the PMKeyS data to 2016 Census records using the linkages of both data sets to the MADIP spine. After removing the records of those ADF members who were out of scope, this resulted in an in-scope population of 72,700 links who were 17 years and over, alive, and ex-serving ADF members at the time of the 2016 Census, who had served at least one day of service between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2015.

Strict separation of identifiable information and analytical content data is maintained within the Data Linkage Units at both AIHW and the ABS, so that no one person or organisation will ever have access to both. Summary results from the linked data set are presented in aggregate format. Personal identifying information is not released, and no individual can be identified in any reporting.

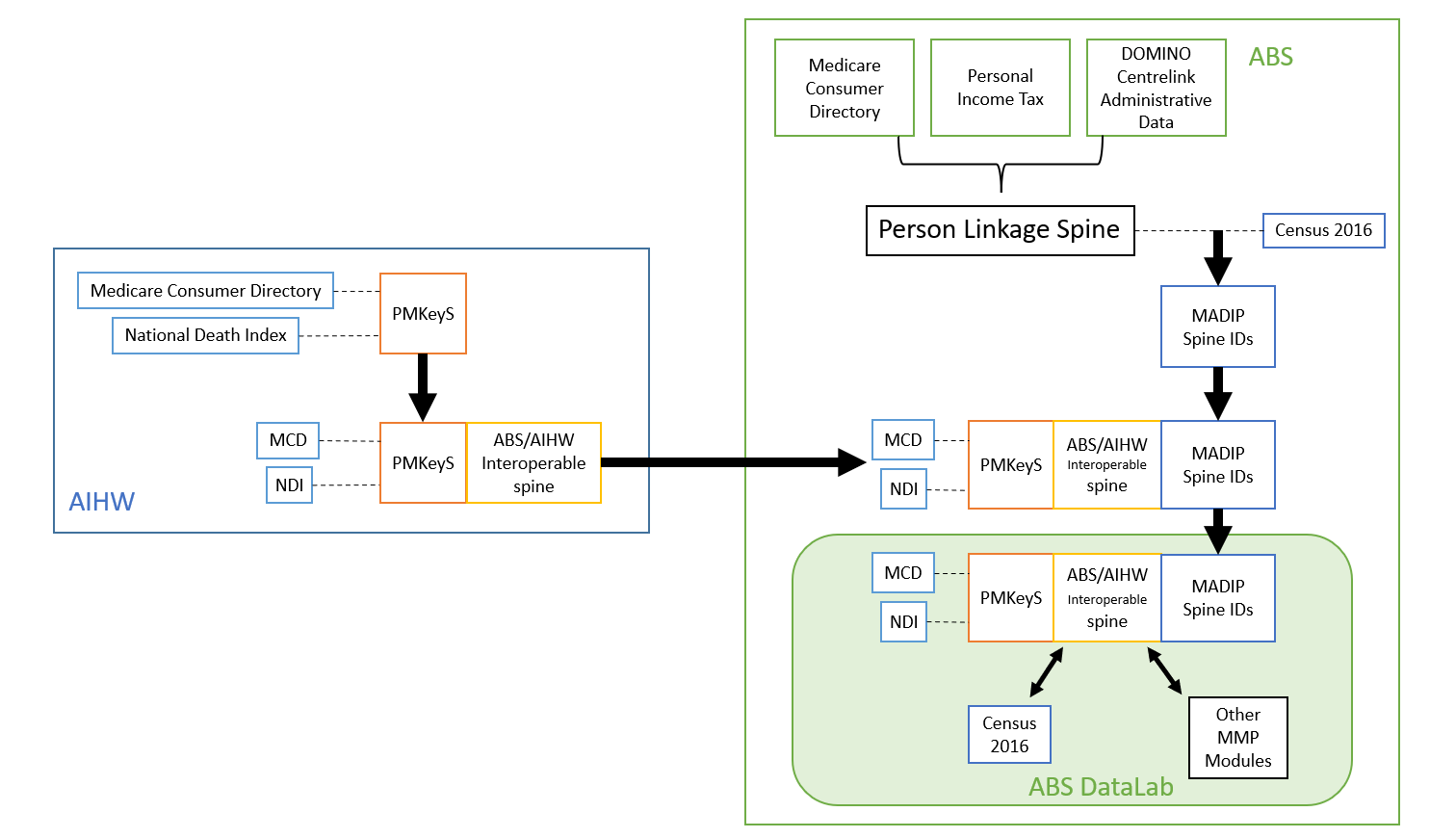

Figure 10 illustrates the linkage process undertaken for this report.

Figure 10: Linkage process

Note: ABS – Australian Bureau of Statistics, AIHW – Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, DOMINO - Data Over Multiple Individual Occurrences, ID – Identification, MCD – Medicare Consumer Directory, NDI – National Death Index, PMKeyS – Personnel Management Key Solution

Age

The minimum age of both the ex-serving ADF and Australian populations was capped at 17 years.

Termination date

As we only had approval to include year of termination date from the PMKeyS data in MADIP, the ex-serving ADF population has been capped at those who terminated before 2016 to ensure ex-serving ADF members had separated from the ADF at the time of the 2016 Census. Termination date is used to calculate length of service and time since separation. The reference date for these service characteristics is 31 December 2015.

Age-standardised percent proportions

Age-standardised rates are rates standardised to a specific standard age structure to facilitate comparison between populations and over time. In this report, they are directly age-standardised rates adjusted using the Australian standard population, that is, the Australian estimated resident population (ERP) as of 30 June 2001.This standard population was used for the ex-serving ADF members and the Australian population. Analysis based on service characteristics has not been age standardised.

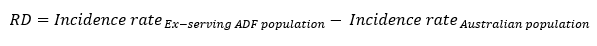

Rate differences

Rate differences (RD), also referred to as absolute differences are presented in data tables that accompany this report. They are a measure the magnitude of the gap between populations without respect to how big or small the individual rates are. RDs are subject to volatility when used with small numbers, and so should be used with caution when comparing ex-serving ADF member results to the Australian population.

The RD is calculated by subtracting the incidence rate of an unexposed population from the incidence rate of the exposed population (LaMorte 2018a).

For the purpose of this report, ‘exposure’ refers to those who have separated from the ADF, i.e., ex-serving. As such, the Australian population is the unexposed population, while the ex-serving ADF member population is the exposed population (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Formula for calculating rate differences

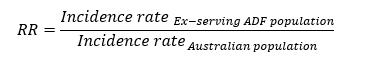

Rate ratios

Rate ratios (RR), also referred to as relative rates, measure the degree of inequality between populations. Unlike RDs, RRs are sensitive to the scale of the rates, and are typically more stable than RDs. Similarly to RDs, RRs are subject to volatility when used with small numbers, and so should be used with caution when comparing ex-serving ADF member results to the Australian population.

The RR is calculated by dividing the incidence rate in an exposed group by the incidence rate in an unexposed group (LaMorte 2018b).

As with RDs, the Australian population is the unexposed population, while the ex-serving ADF member population is the exposed population (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Formula for calculating rate ratios

When a RR is greater than 1, it suggests an increased risk of the outcome in the exposed group. When a RR is less than 1, it suggests a reduced risk of the outcome in the exposed group. If a RR is 1 or close to one, it suggests no difference or little difference in risk (the incidence in each population group is the same).

Estimates from the regression model are presented as odds ratios for the group of interest compared with a reference group for each service and demographic characteristic in the data tables attached to this report. An odds ratio (OR) indicates how many times higher the probability of an event is in one group of people with a particular characteristic than in another group without that characteristic, after adjusting for other factors in the model. The size of the reported odds ratio indicates the strength of the association or relationship a service or demographic characteristic has to wellbeing circumstance (for example, having a bachelor degree, being employed, unemployed or not in the labour force in 2016), relative to the reference group. The odds ratios inform the direction of association with odds ratios greater than 1 showing the outcome was more common than the reference outcome, while odds ratios less than 1 show it is less likely.

Ninety-five per cent (95%) confidence intervals are also presented to indicate the statistical precision and significance. The result is interpreted as having a statistically significant association (that is, not due to chance) if the confidence interval does not cross the value of 1.

The study population does not include ADF members who separated from the ADF before 1 January 2001.

Small sizes

When disaggregating the ex-serving ADF member population by age, sex and wellbeing domains, small populations have been encountered. This has meant occasionally limiting the analysis further, e.g., presenting just person totals, broader age groups or confidentialising small cell counts. This has also limited the utility of RRs and RDs in a couple of areas. Such treatments have been footnoted in the data tables accordingly.

Linkage

The linkage processes only provide data for those ex-serving ADF members who had a 2016 Census record. Reasons why a person may not have a 2016 Census record include they were overseas at the time of the 2016 Census, or they may not have completed a Census form. Some ex-serving ADF members could not be linked to a Census record due to the 2016 Census record not being available in MADIP or the required information was not available in the MADIP to support the linkage.

The Understanding the wellbeing characteristics of ex-serving ADF members report was prepared by AIHW staff in the Veterans Insights and Projects Unit. Valuable advice and guidance were provided by members of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Department of Defence, and the AIHW’s Veterans Advisory Group. The AIHW thanks their DVA and Defence colleagues and Veterans Advisory Group members for their continued support of the DVA-AIHW Strategic Partnership and subsequent work program.

The AIHW also thanks and acknowledges contributions of internal staff from the AIHW including the Ethics Privacy and Legal Unit who facilitated the ethics approval process and the Specialist Capability Unit who provided statistical guidance in the methods used for the analysis.

Special thanks are due to the AIHW Data Integration Services Centre, the Australian Bureau of Statistics Data Integration Division and the MADIP data custodians for making this data linkage project possible.

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

|---|---|

| ADF | Australian Defence Force |

| AIHW | Australian Institute of Health and Welfare |

| DVA | Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

| PMKeyS | Personnel Management Key Solution |

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2016a). Housing Circumstances of People Using Mental Health Services and Prescription Medications. ABS, accessed 8 December 2021.

ABS (2016b). 2901.0 - Census of Population and Housing: Census Dictionary, 2016. ABS, accessed 8 December 2021.

ABS (2018). Labour Statistics: Concepts, Sources and Methods, Feb 2018. ABS, accessed 8 January 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2017). Australia’s welfare 2017. Australia’s welfare series no. 13. Cat. no. PHE 214. AIHW, accessed 8 December 2021.

AIHW (2018a). A profile of Australia's veterans. Cat. no. PHE 235. AIHW, accessed 8 December 2021.

AIHW (2018b). Development of a Veteran-centred model: a working paper. Cat. no. PHE 224. AIHW, accessed 8 December 2021.

AIHW (2021a). Australia’s welfare 2021: in brief. Cat. no. PHE 237. AIHW, accessed 8 December 2021.

AIHW (2021b). Final report to the Independent Review of Past Defence and Veteran Suicides, Demographic and service profile of ADF. AIHW, accessed 8 April 2022.

AIHW (2021c). Older Australians 2021. AIHW, accessed 9 May 2022.

Beyond Blue (2022). Unemployment and mental health. Beyond Blue, accessed 4 May 2022.

Daraganova G, Smart D and Romaniuk H (2018). Family Wellbeing Study: Part 1: Families of Current and Ex-Serving ADF Members: Health and Wellbeing. Department of Defence and Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra.

Defence (Department of Defence) (2017). ADF member and family transition guide: a practical manual to transitioning. Defence, accessed 8 December 2021

Defence (2018). ADF Transition Training & Skills Guide (Various levels). Defence, Canberra.

Defence (2022). Transition. Department of Defence, accessed 4 May 2022.

PMC (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) (2022). Data Integration. PMC, accessed 4 May 2022.

DVA (Department of Veterans’ Affairs) (2011). Mental Health and Wellbeing after Military Service. DVA, accessed 8 August 2022.

DVA (2015). Social Health Strategy 2015–2023, for the veteran and ex-service community. DVA, Canberra.

DVA (2020). 2.7 Medical discharges and ADF Medical Boards. DVA, accessed 5 May 2022.

DVA (2021). Department of Veterans’ Affairs Annual Report 2020-21. DVA, Canberra.

Harrod M, Miller E, Henry J and Zivin K (2017). ‘I’ve never been able to stay in a job: a qualitative study of veterans’ experiences of maintaining employment’. Work, 57:259–68, DOI: 10.3233/WOR-172551

Iversen A, Nikolaou V, Greenberg N, Unwin C, Hull L, Hotopf M, Dandeker C, Ross J, Wessely S (2005). ‘What happens to British veterans when they leave the armed forces?’ European Journal of Public Health, 15(2):175–184, DOI: 10.1093/eurpub/cki128

Lawrence-Wood, E, McFarlane, A, Lawrence, A, Sadler, N, Hodson, S, Benassi, H, Bryant, R, Korgaonkar, M, Rosenfeld, J, Sim, M, Kelsall, H, Abraham, M, Baur, J, Howell, S, Hansen, C, Iannos, M, Searle, A, and Van Hooff, M (2019). Impact of combat report. Defence, DVA, Canberra.

Lin N, Simeone R, Ensel W and Kuo W (1979). ‘Social support, stressful life events, and illness: a model and an empirical test’. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 20:108–19.

MacLean M B, Van Til L, Thompson J M, Sweet J, Poirier A, Sudom K, Pedlar D J (2014). ‘Postmilitary Adjustment to Civilian Life: Potential Risks and Protective Factors’, Physical Therapy, 94(8):1186–1195, DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20120107

Open Arms (2021). Reconnecting after deployment or absence. Open Arms, accessed 8 August 2022.

Ozbay F, Johnson DC, Dimoulas E, Morgan CA, Charney D and Southwick S (2007). ‘Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice’. Psychiatry; 4:35–40.

Palumbo L (2019). The impact of mental health, service and transition factors on civilian unemployment in transitioned Australian Defence Force members [masters thesis], University of Adelaide, accessed 8th August 2022.

SA (Services Australia) 2021. Income, Services Australia, accessed 8 December 2021.

Sadler, N (2019). ‘Veterans have poorer mental health than Australians overall. We could be serving them better’. The Conversation.

Tan C (2020). Australian Defence Force Families research 2019, Directorate of People lntelligence and Research, Department of Defence, Canberra.

Van Hooff M, Lawrence-Wood E, Hodson S, Sadler N, Benassi H, Hansen C, Grace B, Avery J, Searle A, Iannos M, Abraham M, Baur J, and McFarlane A (2018), Mental Health Prevalence, Mental Health and Wellbeing Transition Study, Defence and DVA, Canberra.

Van Hooff M, Lawrence-Wood E, Sadler N, Hodson S, Benassi H, Daraganova G, Forbes D, Sim M, Smart D, Kelsall H, Burns J, Bryant R, Abraham M, Baur J, Iannos M, Searle, A, Ighani H, Avery J, Hansen C, Howell S, Rosenfeld J, Lawrence A, Korgaonkar M, Varker T, O’Donnell M, Phelps A, Frederickson J, Sharp M, Saccone E, McFarlane, A, and Muir, S (2019). Transition and Wellbeing Research Programme Key Findings Report. Defence and DVA, Canberra.

von Sanden N (2020). ‘Improving Inter-Agency Data Sharing Through Linkage Spine Interoperability’, International Journal of Population Data Science, 5(5). DOI: 10.23889/ijpds.v5i5.1577.

Comprehensive data tables from this analysis are available online. See Data under the Veterans topic.