Prevalence and impact of mental illness

1 in 5 Australians

aged 16–85 (22%, or 4.3 million) experienced a mental disorder.

17% of Australians experienced an Anxiety disorder

8% experienced an Affective disorder and 3% a Substance use disorder.

1 in 7 children and adolescents

aged 4–17 years experienced a mental illness.

Mental health is a key component of overall health and wellbeing (WHO 2021). A mental illness can be defined as ‘a clinically diagnosable disorder that significantly interferes with a person’s cognitive, emotional or social abilities’ (COAG Health Council 2017). However, a person does not need to meet the criteria for a mental illness or mental disorder to be negatively affected by their mental health (COAG Health Council 2017; Slade et al. 2009).

On this page, the terms ‘mental illness’ and ‘mental disorder’ are both used to describe a range of mental health and behavioural disorders, which can vary in both severity and duration.

There are multiple surveys which collect information on the extent of mental illness in the Australian population. This page collates evidence on the prevalence and impact of mental illness. For more information about specific surveys, refer to data sources.

How many Australians have experienced mental illness?

The following estimates come from the National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW), the most robust measure of mental illness prevalence for Australia. It included an in-person interview using the World Health Organization’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3.0. This instrument indicates diagnoses, rather relying on participant’s self-reporting of conditions (ABS 2023b).

Of Australians aged 16–85 from 2020 to 2022, an estimated:

- 8.5 million had experienced a mental disorder at some time in their life (43% of the population).

- 4.3 million had experienced a mental disorder in the previous 12 months (22% of the population; Figure 1).

The most common mental illnesses in Australia, in the 12 months prior to the study, were:

- Anxiety disorders (3.4 million people, or 17% of the population)

- Affective disorders (1.5 million, or 8%)

- Substance Use disorders (650,000, or 3%) (ABS 2023a).

Figure 1: Lifetime and 12-month mental illness, by type and sex, 2020 to 2022

Figure 1.1 Bar chart showing the estimated number of male and female Australians aged between 16 and 85 experiencing any of 12 mental disorders, either over their lifetime or in the previous 12 months. An estimated 4,263,122 Australians in this age group (22% of this population) have experienced a mental disorder over the previous 12 months.

Figure 1.2 Bar chart showing the estimated proportion of Australians who reported that they have been diagnosed with a serious mental illness in the previous 12 months, by sex and age group. Figures available for 2009, 2013, 2017, 2020 and 2021. The total proportion has risen from 11% in 2009 to 19% in 2021.

Figure 1.3 Line graph showing estimated proportion of Australians who report that they have a long-term mental health condition, by sex and age group, 2003 to 2021. The total proportion of males has risen from 3% to 5% and females from 3% to 5%.

Source: National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2020–2022; Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey 2021

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) National Health Survey (NHS) 2020–21 provides information on a range of health conditions, including self-reported mental and behavioural disorders. The NHS records a person as having a mental or behavioural condition during the collection period only if the person reports that the condition had lasted, or was expected to last, 6 months or longer. According to the 2020–21 NHS, 1 in 5 (20%) Australians aged 15 and over were estimated to have had a mental or behavioural condition during the collection period (August 2020 to June 2021) (ABS 2022b).

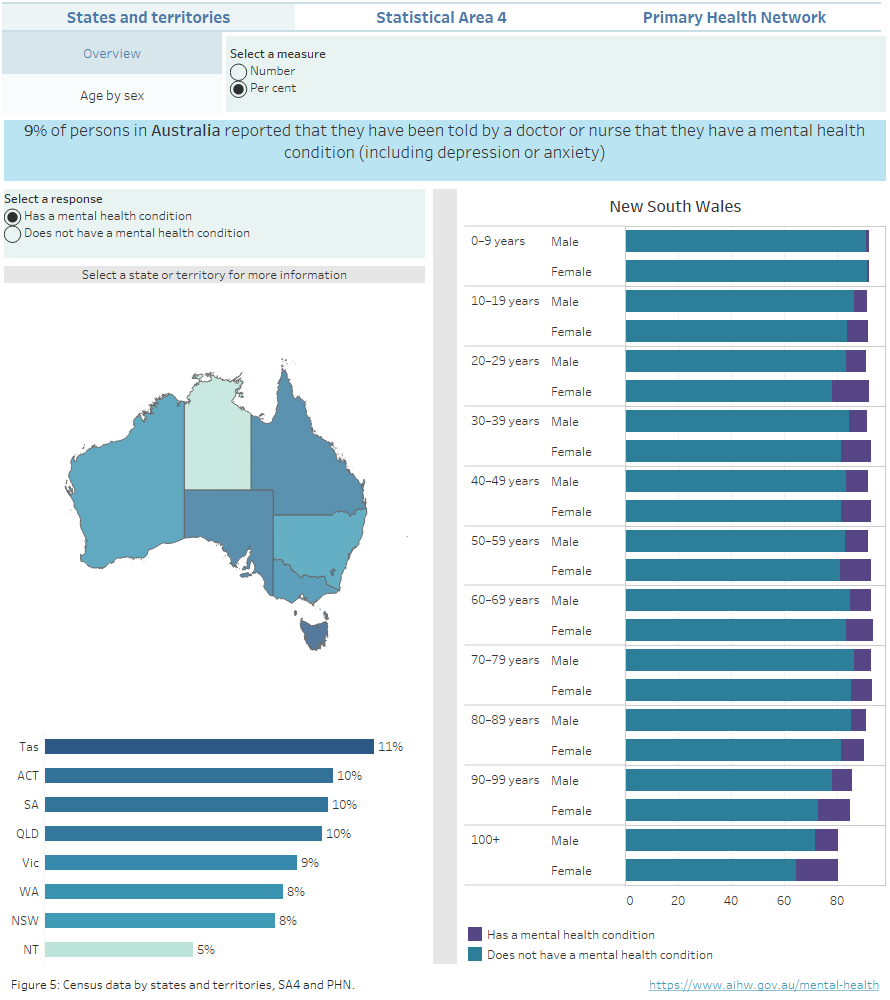

In the 2021 Census of Population and Housing (the Census) – which includes people of all ages – over 8 million Australians (32%) reported that they had been told by a doctor or nurse that they have a long-term health condition, with 2.2 million (9%) reporting a mental health condition (including depression or anxiety) (ABS 2022a). Although the Census provides valuable information, the ABS recommends that the NSMHW be used as the reference source for mental illness prevalence data as it uses diagnostic criteria, rather than the self-reporting approach used in the Census and other surveys (ABS 2022c).

Similarly, the Household Income Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) is a household-based panel study that collects information including personal wellbeing. The HILDA survey asks participants whether they have been told by a doctor or nurse that they have a serious mental illness, such as depression or anxiety, or a long-term mental health condition. In 2021, an estimated 19% of Australians reported being diagnosed with depression, anxiety or any other serious mental illness at some time in their life, an increase from 11% in 2009. In addition, 6% of Australians reported having a long-term mental health condition such as a mental illness which requires help or supervision, or a nervous or emotional condition which requires treatment.

Mental illness includes conditions with relatively low prevalence and potentially severe consequences, such as psychotic illnesses (Department of Health and Ageing 2010). Psychotic illnesses may be characterised by symptoms including disordered thinking, hallucinations, delusions and disordered behaviour, although individual experiences vary greatly. Diagnoses include Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective disorder and Delusional disorder.

The 2010 National Psychosis Survey estimated that 64,000 Australians aged 18–64 experienced a psychotic illness and were in contact with public specialised mental health services each year. This equates to 5 cases per 1,000 population. The survey found the most frequently recorded of these disorders was Schizophrenia which accounted for almost half of all diagnoses (47%) (Morgan et al. 2011).

Change over time

Prior to 2020–2022, the NSMHW was last undertaken in 2007. Between the two surveys, prevalence of mental illness among the Australian population remained broadly similar, with 45% of Australians aged 16–85 years having a lifetime mental disorder in 2007, compared with 43% in 2020–2022. In 2007, an estimated 20% of Australians had a 12-month mental disorder, compared with 22% in 2020–2022.

Between the two surveys, the prevalence of a 12-month mental disorder remained the same among males (18% for both), but there was an increase among females (from 22% in 2007 to 25% in 2020–2022).

While the prevalence of a 12-month mental disorder remained broadly similar between the two surveys for people aged 25–85, there was a marked increase among young adults. In 2007, 26% of those aged 16–24 had a 12-month mental disorder; in 2020–2022, this figure was 39%. This change is almost entirely driven by an increased prevalence of mental illness among females in this age group: 30% of females aged 16–24 years in 2007 had a 12-month disorder, compared with 46% in 2020–2022 (the prevalence for males of this age group increased from 23% to 32%).

Changes in methodology and diagnostic criteria mean that some comparisons between the 2007 and 2020–2022 studies should be made with caution. For more information, refer to Data interpretation.

Age and sex

Prevalence of mental illness varies by age and sex. Mental illness prevalence has increased more rapidly than prevalence of other serious illnesses; this increase has been more pronounced for young women (aged 15–34). In 2021, double the proportion of females aged 20–29 reported that they had been told by a doctor or nurse that they have a mental health condition compared to males the same age (16% and 8%, respectively) (ABS 2022a)

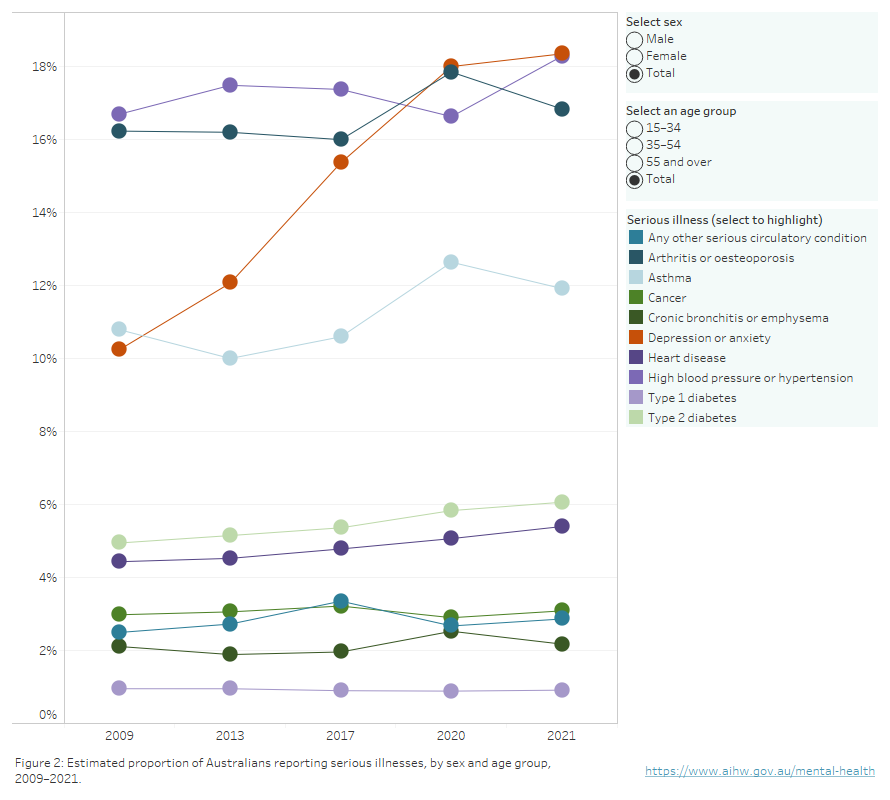

According to the HILDA survey, in 2021, the estimated prevalence of depression or anxiety was highest among younger women and men (aged 15–34) at 22%, compared to 15% for people aged 55 and over. Since 2017, mental illness prevalence rates exceed asthma, which had been the most common serious illness for this age group (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Types of serious illness by age and sex, 2009 to 2021

Line graph showing estimated prevalence of serious illnesses in Australia by sex and age group. Figures available for 2009, 2013, 2017, 2020 and 2021. Depression or anxiety have the highest prevalence rate in Australia among all serious illnesses included in the HILDA survey in 2020 and 2021.

Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey 2021

The HILDA Survey provides data which allows the persistence of serious illness to be considered. The 2021 survey results showed that:

- 61% of males who were diagnosed with depression or anxiety in 2017 reported still having the condition 4 years later.

- 71% of females who were diagnosed with depression or anxiety in 2017 reported still having the condition 4 years later.

- 70% of people aged 15–34 who were diagnosed with depression or anxiety in 2017 reported still having the condition 4 years later.

- 69% of people aged 35–54 who were diagnosed with depression or anxiety in 2017 reported still having the condition 4 years later.

- 64% of people aged 55 and over who were diagnosed with depression or anxiety in 2017 reported still having the condition 4 years later.

In addition, of those who accessed treatment for their depression or anxiety diagnosis in 2017:

- 74% reported still having the condition 4 years later.

- 9% reported not having the condition but having other serious illness 4 years later.

- 17% reported not having any serious illness 4 years later.

Similarly, of those who took prescribed medication for their depression or anxiety diagnosis in 2017:

- 76% reported still having the condition 4 years later.

- 6% reported not having the condition but having other serious illness 4 years later.

- 18% reported not having the condition 4 years later.

In addition to diagnoses, the HILDA Survey tracks the mental health of Australians based on the MHI-5 mental health measure (a subscale of the SF-36 general health measure). This measure ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores suggesting better mental health.

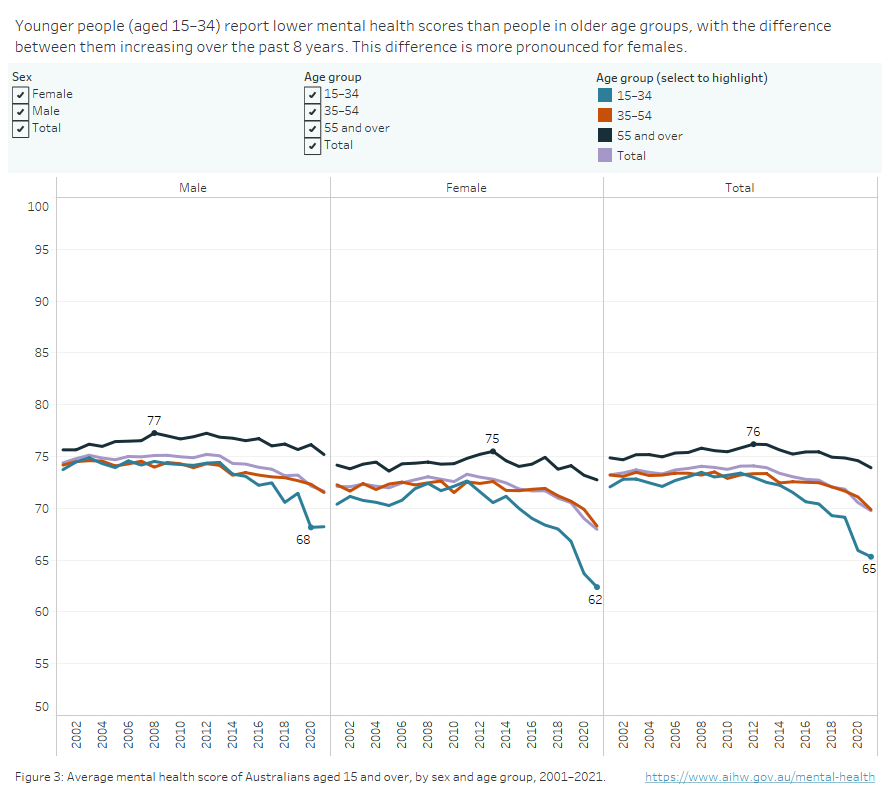

The average mental health score in Australia remained around 74 from 2001 to 2012. From 2013, it started decreasing until reaching 70 in 2021. Females maintained a lower average mental health score than males over this time (Figure 3).

People aged 15–34 had lower mental health scores than those in older age groups. Moreover, this gap has been increasing as mental health scores for younger people decrease at faster rates over the past 8 years. The average mental health score for people aged 15–34 decreased from 72 in 2001 to 65 in 2021. This difference is more pronounced for females, whose score decreased from 70 to 62 over this time. Females aged 55 and over recorded an average mental health score of 73 in 2021 compared with younger females (aged 15–34) who recorded an average score of 62.

Figure 3: Average mental health score of Australians aged 15 and over by sex, 2001–2021

Line graph showing average mental health score of Australians by sex and age group, 2001 to 2021. Australians aged 15–34 have the lowest average mental health score of all age groups.

Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey 2021

Children and adolescents

The second, and most recent, national survey of the mental health and wellbeing of Australian children and adolescents was undertaken in 2013–14, with almost 3,000 people aged 4–17 participating. The survey included a structured diagnostic interview to assess young people against mental disorder criteria (Lawrence et al. 2015).

Almost 1 in 7 (14%) children and adolescents aged 4–17 years were estimated to have experienced mental illness in the previous 12 months, which is equivalent to about 628,000 people (based on the estimated 2022 population). The most common mental illnesses among children and adolescents were:

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (7%, or about 334,000 people)

- Anxiety disorders (7%, or about 312,000)

- Major depressive disorder (3%, or about 126,000)

- Conduct disorder (2%, or about 95,000).

Almost one-third (30%) of adolescents with a mental illness experienced 2 or more mental illnesses at some time in the previous 12 months.

Male children and adolescents (16%) were more likely than females (12%) to have experienced mental illness in the previous 12 months. The prevalence of mental illness was slightly higher for older females (13% for those aged 12–17) than for younger females (11% for those aged 4–11). However, the prevalence for males did not differ markedly between the younger and older age groups (17% and 16%, respectively) (Lawrence et al. 2015).

In 2021, HILDA estimates showed that around 7% of Australians aged 15–17 had a long-term mental health condition such as a nervous or emotional condition which requires treatment, or a mental illness which requires help or supervision. This proportion has increased from 2% in 2003. In addition, 19% of Australians in this age group were estimated to be diagnosed with depression, anxiety or any other mental illness, an increase from 6% in 2009.

- 27% of female adolescents (aged 15–17) reported being diagnosed with a serious mental illness in 2021; an increase from 16% in 2017. In comparison, 11% of male adolescents reported a serious mental illness, showing no change from 2017.

- 25% of female adolescents self-reported being diagnosed with anxiety in 2021; an increase from 15% in 2017. In comparison, 9% of male adolescents reported an anxiety diagnosis, an increase from 8% in 2017.

- 13% of female adolescents self-reported being diagnosed with depression in 2021; an increase from 7% in 2017. In comparison, 4% of male adolescents reported a depression diagnosis, a decrease from 6% in 2017.

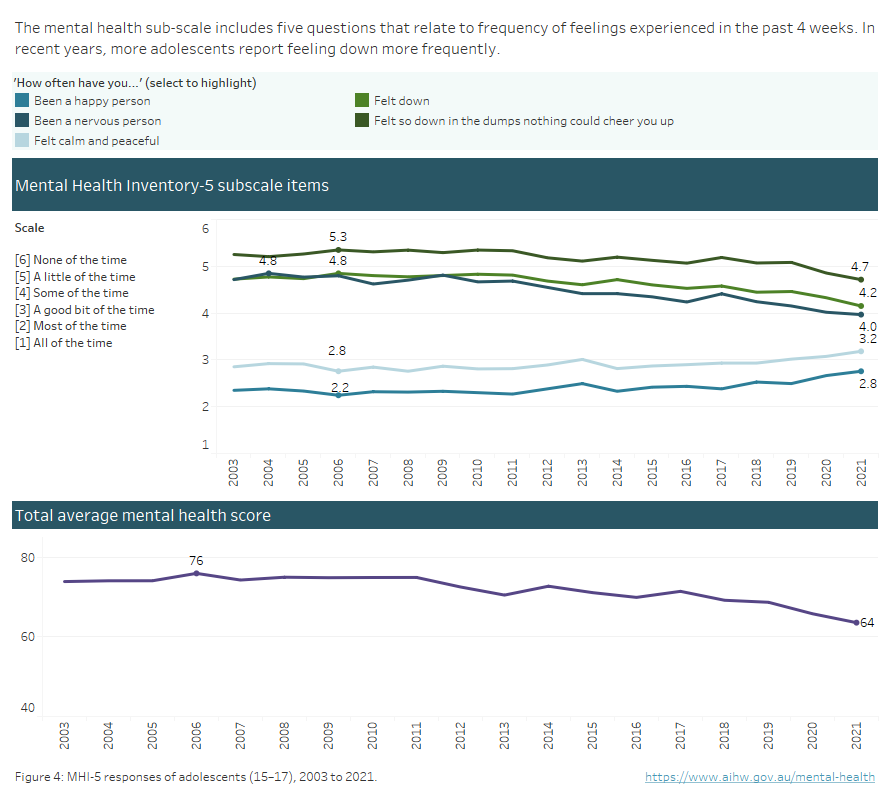

In 2021, more adolescents reported frequently feeling ‘so down in the dumps nothing could cheer you up’ compared with 2008. The average score for this question has decreased from a high of 5.3 in 2008 to a low of 4.7 in 2021. The average score for the question ‘felt calm and peaceful’ has increased from 2.8 to 3.2, indicating that fewer adolescents report feeling like that frequently (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Experience of mental health among people aged 15–17 years, 2003 to 2021

Line graph showing average mental health score and sub score of Australians aged 15–17, 2001 to 2021. The average mental health score of Australians ages 15–17 has decreased from a high of 76 in 2006 to a new low of 64 in 2021.

Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey 2021

How does mental health differ across Australia?

In 2021, the Census included new questions on 10 common long-term health conditions. Some insights gleaned from the Census include:

- 11% of people who usually reside in Tasmania have been told by a doctor or nurse that they have a mental health condition, the highest proportion of any state or territory.

- People who have no usual address tend to report a higher proportion of mental health conditions than people usually residing in fixed geographic areas (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Census data by states and territories, SA4 and PHN

Interactive data visualisation comparing reported mental illness between states and territories, Primary Health Networks and statistical areas.

Source: AIHW analysis of Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022) Census TableBuilder

Note: Percentages may not sum to 100 due to due to rounding and confidentialisation. Refer to the data tables for more information.

Impact of mental illness

The HILDA Survey collects information on the extent to which health conditions impact an individual’s everyday activities. In 2021, for people who reported having a long-term mental health condition:

- 17% reported needing help or supervision due to their condition.

- More than half (59%) of people aged less than 65 reported having difficulties with employment due to their condition. These difficulties included needing ongoing assistance or special equipment to work, having to restrict number of work hours or type of work they can do, among others.

- More than half (58%) of students aged less than 65 had difficulties with education due to their condition.

The HILDA Survey also collects information on the degree to which health conditions limit the amount of work an individual can do (on a 0 to 10 scale, where 0 equals ‘not at all’ and 10 equals ‘unable to do any work’). In 2021, around 2 in 3 (68%) persons reported that their condition limits the type or amount of work they can do, of these, about half reported a score higher or equal to 7, with 12% scoring 10 ‘unable to do any work’.

An estimated 24% (187,500) of First Nations people reported a mental health disorder or behavioural condition, based on the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey. The rate was slightly higher among females than males (25% compared with 23%, respectively). An estimated 31% of people reported experiencing high or very high levels of psychological distress in the previous 4 weeks (ABS 2019). For more information, refer to Indigenous health and wellbeing.

The acronym LGBTIQ+ is used here as an umbrella term to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans/transgender, intersex, queer and other sexuality, gender and bodily diverse people and communities.

LGBTIQ+ people report lower health and wellbeing compared to other Australians generally. A survey of LGBTIQ+ people, the Private Lives Survey, has been conducted 3 times since 2005. The most recent survey, undertaken in 2019, was completed by about 6,800 participants. Whilst this survey included participants with an intersex variation/s, the data are not able to be disaggregated by this category and, therefore, the acronym LGBTQ+ is used when referring to the PL3 results. LGBTIQ+ is used when referring to communities more generally.

In 2020, 3 in 5 (61%) of LGBTQ+ people reported having been diagnosed with depression and almost 1 in 2 (47%) reported having been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. Over half (57%) reported experiencing high or very levels of psychological distress within the past 4 weeks.

Survey results showed that 59% of LGBTQ+ people who accessed a mainstream medical clinic felt that their sexual orientation was very or extremely respected. Less than 2 in 5 (38%) thought that their gender identity was very or extremely respected (Hill et al. 2020). For more information, refer to Private Lives 3.

Adults with disability generally experience higher psychological distress than people without disability. According to the National Health Survey, it was estimated that, in 2017–18, 32% of adults with disability experienced high or very high psychological distress in the previous week, compared with 8% of the population without disability. People with psychological disability were the most likely to report high or very high psychological distress (76%), followed by people with intellectual disability (60%) (AIHW 2020).

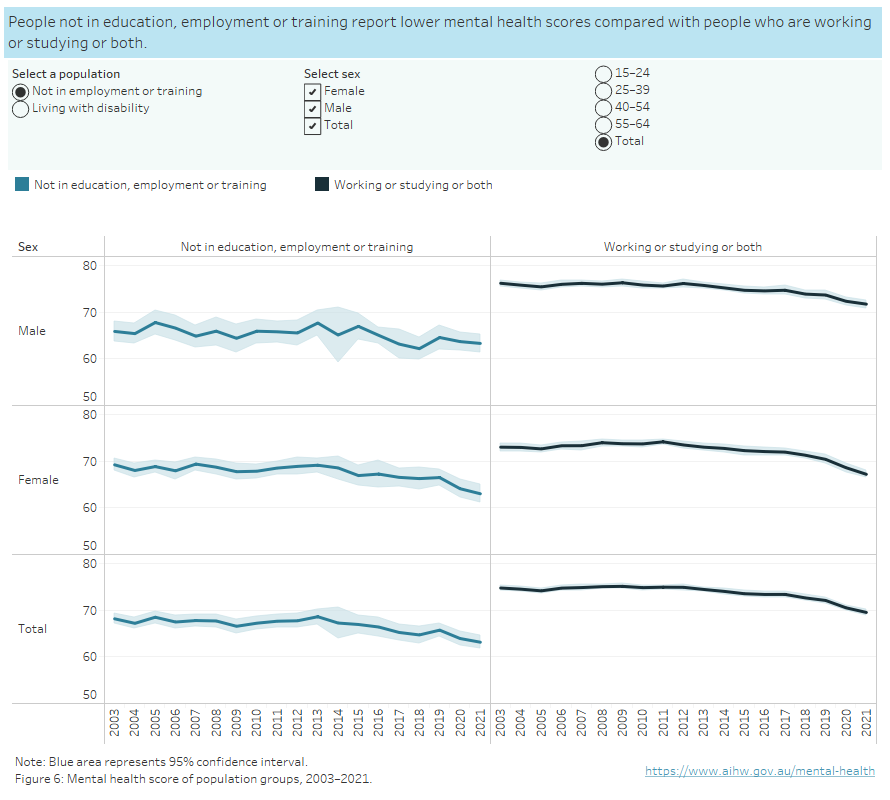

In 2021, the HILDA survey estimated that the average mental health score of people living with disability (impairment or disability that restricts the individual in everyday activities, and which has lasted, or is likely to last, for six months or more (Wilkins et al. 2019)) is consistently lower than those who do not live with disability (62 compared to 72). For females with disability the score is even lower (60) (Figure 6). For more information, refer to People with disability in Australia.

The HILDA survey allows to identify people aged 15–64 who are not employed, not enrolled in education and not enrolled in any course or training (NEET). Young people who are NEET are at risk of becoming socially excluded by lacking the skills to improve their socioeconomic situation (OECD 2023).

The HILDA survey estimates that the average mental health score of the NEET population is consistently lower than those who work, study or both (in 2021, 70 compared to 63).

Even though the mental health score of younger people is the lowest among all age groups, young people aged 15–24 who are either studying or working or both, consistently maintain a higher average mental health score than those who are not (in 2021, 64 compared to 61). In particular, during the first year affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), the average mental health score of young NEETs (aged 15–24) dropped to a new low of 58 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Mental health of selected population groups by age and sex, 2003 to 2021

Line graphs comparing people not in education, employment or training and people living with disability with people not in these populations.

Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey 2021

Burden of mental illness

Severity

Mental illness affects all Australians, either directly, for those who experience it or indirectly, such as family members, friends and carers. Mental illness can vary in severity and be episodic or persistent in nature. In most cases, the impact on the individual will be mild (9%, or an estimated 1.4 million people) or moderate (5%, or an estimated 710,000 people). It is estimated that around 3% (or an estimated 500,000 people) have a severe mental illness, of which 330,000 people have episodic mental illness and 170,000 have persistent mental illness (Whiteford et al. 2017).

Burden of disease

Mental and substance use disorders, such as depression, anxiety and drug use, are substantial components of overall disability and morbidity. The Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023 examined the health loss due to disease and injury that is not improved by current treatment, rehabilitative and preventative efforts of the health system and society. For Australia, Mental and substance use disorders were estimated to be responsible for 15% of the total burden of disease, placing it second as a broad disease group after Cancer (17%) (AIHW 2023).

How many Australians experience psychological distress?

What is psychological distress?

Another insight into the mental health and wellbeing of Australians is provided by measures of psychological distress, which may include nervousness, agitation, psychological fatigue and depression. This distress can result in having negative views of the environment, others and oneself, and manifest as symptoms of mental illness, including anxiety and depression.

How is psychological distress measured?

Psychological distress is commonly measured using the Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10), a scale based on questions regarding negative emotional states experienced in the past 30 days (ABS 2012). Someone experiencing psychological distress will not necessarily be experiencing mental illness, although high scores on the K10 are strongly correlated with the presence of depressive or anxiety disorders (Andrews and Slade 2001). As it is relatively straightforward to measure, High and Very high levels of psychological distress are often used as a proxy for the presence of mental illness.

Surveys which measure psychological distress include the National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, the National Health Survey and the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey.

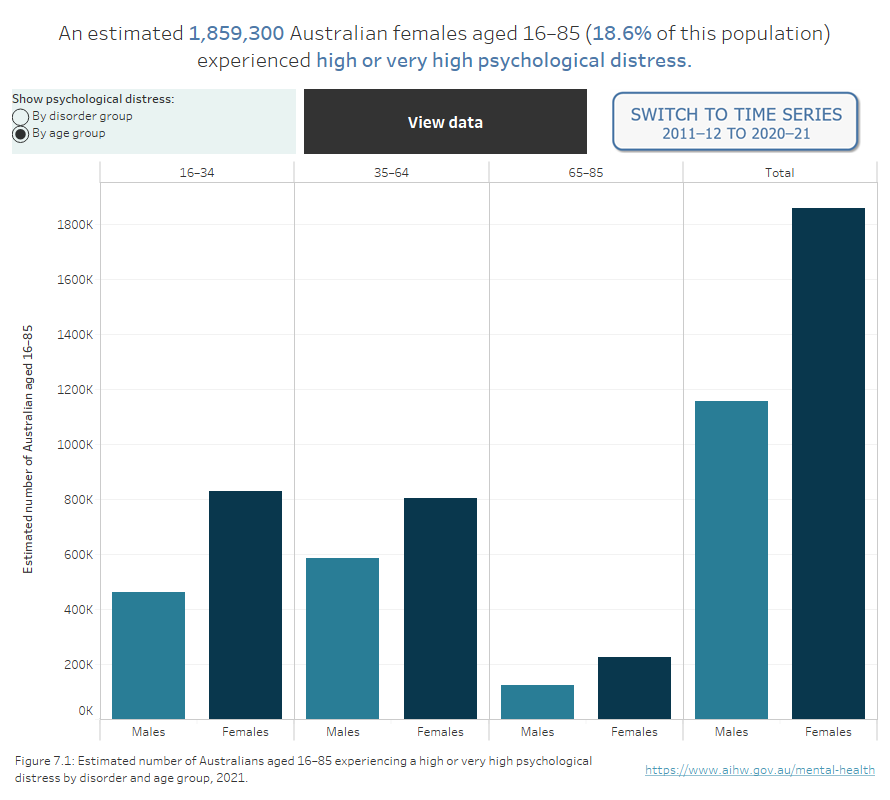

Among Australians aged 16–85, as measured from late 2020 to mid-2021, 15% experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress. Females aged 16–34 were more likely to experience psychological distress than males of this age group (26% compared with 14%) (Figure 7) (ABS 2023a). For more information on psychological distress, refer to the AIHW suicide and self-harm monitoring site.

Figure 7: Estimated number of Australians aged 16–85 experiencing psychological distress, 2021

Bar chart showing the estimated number of male and female Australians aged between 16 and 85 experiencing high or very high psychological distress, either by disorder group or age group.

Source: National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2021; National Health Survey 2011–12, 2020–21

Where can I find more information?

For more information, refer to:

- AIHW – Australian Burden of Disease Study 2022

- ABS – Census of Population and Housing 2021

- ABS – National Health Survey methodology

- ABS – National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing.

- Melbourne Institute – Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia

Data interpretation

Reported prevalence in this section may diverge from actual prevalence because of potential undiagnosed conditions. The calculated prevalence rates are influenced by how prone individuals are to access mental health care services. This is unlikely to be the same across demographic groups (Wilkins et al. 2019).

In this section, measures of statistical uncertainty pertaining to estimates (95% confidence intervals) are shown in all data tables and represented in data visualisations by black bars or shaded area surrounding lines. If the intervals for comparison groups do not overlap – that is, they do not include the same values in the range – the difference between groups can be generally inferred to be statistically significant.

Although the 2020–2022 NSMHW was designed to be broadly comparable with the 2007 survey, changes in methodology and diagnostic criteria mean that some comparisons should be made with caution (ABS 2023c). These include:

- Comorbidity of physical health conditions and mental disorders

- Agoraphobia with Panic Disorder

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

The National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is a component of the wider Intergenerational Health and Mental Health Study (IHMHS) funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023).

Data for the 2020–2022 NSMHW was collected in the Survey of Health and Wellbeing (SHWB) by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), across 2 cohorts, comprising around 10,000 households. The first cohort was conducted between December 2020 and July 2021. The second cohort was conducted from December 2021 to October 2022. The survey included an in-person interview using the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 3.0, which an instrument which indicates potential diagnoses (ABS 2023b).

The objectives of the NSMHW are to provide information in 5 key areas:

- How many Australians have mental disorders?

- What is the impact of these disorders?

- How many people have used services and what are the key factors affecting this?

- Are services making a difference to the lives of people experiencing a mental illness?

- How many Australians have a lived experience of suicide and what services have they used?

Data presented on this page were extracted using the ABS TableBuilder. There may be some differences between this data and that published elsewhere, due to different calculation or estimation methodologies and extraction dates. The TableBuilder uses a randomisation technique to confidentialise small numbers. This can result in differences between totals and small variations in numbers from one data extract to another.

For more information, see National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing methodology, 2020–2022.

The National Health Survey (NHS), run by the ABS, collects data on the health of Australians including health conditions, health risk factors and demographic and socio-economic information. It is part of a series of national health surveys conducted by the ABS since 1977. The 2020–21 NHS was conducted from August 2020 to June 2021. Data was collected from approximately 11,000 households around Australia (ABS 2022d).

The survey focused on the health status of Australians and health-related aspects of their lifestyles. Information was collected about respondents' long-term health conditions and on lifestyle factors which may affect health, such as tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, sugar sweetened and diet drink consumption, and physical activity. Self-reported health status, height, weight, body mass, and use of health services were also collected.

The survey also collected a standard set of information about respondents including age, sex, country of birth, main language, employment, education, and income.

Data presented on this page were extracted using the ABS TableBuilder. There may be some differences between this data and that published elsewhere due to different calculation or estimation methodologies and extraction dates. The TableBuilder uses a randomisation technique to confidentialise small numbers. This can result in differences between totals and small variations in numbers from one data extract to another.

For more information, see National Health Survey: First Results methodology, 2020–21.

The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey is a household-based panel study that collects information about economic and personal wellbeing, labour market dynamics and family life. This survey was first collected in 2001. Information collected includes family relationships, income and employment, and health and education. The HILDA Survey follows the lives of more than 17,000 Australians each year, aiming to tell the stories of the same group of Australians over the course of their lives.

Refer to the HILDA Technical Paper Series: Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research for more information.

Also known as Young Minds Matter, the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing survey was conducted between June 2013 and April 2014 in the homes of over 6,300 families with children and/or adolescents aged 4 to 17 (Lawrence et al. 2015).

The objectives of the survey were to determine:

1. How many children and adolescents have mental health problems and disorders.

2. The nature of these mental health problems and disorders.

3. The impact of these mental health problems and disorders.

4. How many children and adolescents have used services for mental health problems and disorders.

5. The role of the education sector in providing services for children and adolescents with mental health problems and disorders.

Mental disorders were assessed using specific diagnostic modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV) and a specifically developed Impact on Functioning module. DISC-IV modules for seven disorders were included in the survey:

- Anxiety disorders: Social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Major depressive disorder.

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

- Conduct disorder (Lawrence et al. 2015).

For more information, refer to The mental health of children and adolescents.

The 2010 Survey of High Impact Psychosis (SHIP) is Australia’s second national psychosis survey. The survey covered 1.5 million people aged 18–64 years, approximately 10% of Australians in this age group. A two-phase design was used. In phase 1, screening for psychosis took place in public mental health services and non-government organisations supporting people with mental illness. For the second phase, 1,825 of those who screened-positive for psychosis were randomly selected and interviewed. Data collected included symptomatology, substance use, functioning, service utilisation, medication use, education, employment, housing, and physical health including fasting blood samples (Morgan et al. 2011).

The 2021 Census of Population and Housing (the Census) aimed to count every person in Australia on Census Night, 10 August 2021.

The people counted in the Census include:

- people in the six states and six territories (Northern Territory, Australian Capital Territory, Jervis Bay Territory, Territory of Christmas Island, Territory of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Norfolk Island)

- people who leave Australia but are not required to undertake migration formalities (e.g., people who work on oil or gas rigs)

- people on vessels in or between Australian ports

- people on board long-distance trains, buses or aircrafts within Australia

- people entering Australia before midnight on Census Night

- visitors to Australia (regardless of how long they have been in the country or plan to stay)

- detainees under the jurisdiction of the Department of Home Affairs in detention centres in Australia

- people in police lock-ups and prisons.

The people not counted in the 2021 Census include:

- people in Australian external territories (minor islands such as Heard and McDonald Island)

- foreign diplomats and their families (derived from the Vienna Convention)

- foreign crew members on ships who remain on the ship and do not undertake migration formalities

- people leaving an Australian port for an overseas destination before midnight on Census Night.

The 2021 Census of Population and Housing also counted private dwellings (such as houses, apartments and caravans) and non-private dwellings (such as hotels, hostels and hospitals).

The dwellings counted in the 2021 Census include:

- all occupied and unoccupied private dwellings

- occupied caravans in caravan parks and manufactured homes in manufactured home estates

- occupied non-private dwellings, such as hospitals, prisons, hotels, etc.

- unoccupied residences in retirement villages (self-contained)

- unoccupied residences of owners, managers or caretakers of such establishments.

Unoccupied non-private dwellings were out of scope of the 2021 Census.

Data presented on this page were extracted using the ABS TableBuilder. There may be some differences between this data and that published elsewhere due to different calculation or estimation methodologies and extraction dates. The TableBuilder uses a randomisation technique to confidentialise small numbers. This can result in differences between totals and small variations in numbers from one data extract to another.

For more information, refer to Census methodology, 2021.

The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society (ARCSHS) at La Trobe University runs Australia’s largest targeted surveys of LGBTQ+ adults, the Private Lives and Writing Themselves In surveys, respectively (Hill et al. 2020). The most recent iteration of this survey, Private Lives 3 (PL3), was undertaken in 2019. The PL3 dataset is the largest and most comprehensive available for the LGBTQ+ population in Australia and includes a diverse sample of participants from all states and territories and demographic groups (Hill et al. 2020).

A limitation of PL3 and other targeted, community surveys of LGBTQ+ people is that they tend not to be based on probability sampling and, as a result, it is not possible to conclude that they provide representative data for the LGBTQ+ population. However, these surveys do provide important information about the survey respondents, which can inform the work of LGBTQ+ researchers and advocates, and policy makers. For more information, refer to Private Lives 3.

Key concept | Description |

|---|---|

Burden of disease | Burden of disease is measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) – years of life lost due to premature mortality (fatal burden) and years of healthy life lost due to poor health (non-fatal burden). |

Episodic mental illness | An episodic mental illness is characterised by acute episodes of symptoms, which may be severe and disabling, with periods of minimal symptoms or remission. |

Long-term health condition | In the HILDA survey, a long-term health condition, is one that restricts everyday activities and has lasted or is likely to last for six months or more. |

Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) | The MHI-5 is a questionnaire used to screen for depressive and anxious symptoms. It consists of 5 questions about how people have been feeling during the past 4 weeks. Responses are recorded on a scale of 1 to 6, where 1 equates to ‘All of the time’ and 6 ‘None of the time’. |

Persistent mental illness | In persistent mental illness, the severity and impact of symptoms may fluctuate but remain chronic and may be disabling. |

Prevalence | Prevalence measures the proportion of a population with a particular condition during a specified period of time (period/point prevalence), usually measured over a 12-month period or over the lifetime of an individual (lifetime prevalence). |

Serious illness | In the HILDA survey, a serious illness is any illness which has lasted or is likely to last for six months or more. |

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) | The SF-36 is a widely used 36 item questionnaire covering a range of physical health, mental health and wellbeing measures. It can be used to make comparisons between groups and quantify disease burden. |

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2012) Information paper: Use of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in ABS health surveys, Australia, 2007–08, ABS cat. no. 4817.0.55, ABS, Canberra, accessed 10 January 2024

ABS (2019) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2022a) Long-term health conditions, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2022b) Health Conditions Prevalence, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2022c) Comparing ABS long-term health conditions data sources, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2022d) National Health Survey: First Results Methodology, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2023a) National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2023b) National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing methodology, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

ABS (2023c) Microdata: National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2020) People with disability in Australia, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

AIHW (2023) Australian Burden of Disease Study 2023, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

Andrews G and Slade T (2001) ‘Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10)’, Australia and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(6): 494–497, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x, accessed 110 January 2024.

COAG (Council of Australian Governments) Health Council (2017) The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan, Department of Health, Canberra, accessed 10 January 2024.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Intergenerational Health and Mental Health Study, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

Department of Health and Ageing (2010) National mental health report 2010: summary of 15 years of reform in Australia’s mental health services under the National Mental Health Strategy 1993-2008, Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government, accessed 10 January 2024.

Hill AO, Bourne A, McNair R, Carman M and Lyons A (2020) Private Lives 3: The health and wellbeing of LGBTIQ people in Australia, ARCSHS Monograph Series No. 122, Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, La Trobe University, Melbourne, accessed 10 January 2024.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven de Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J and Zubrick SR (2015) The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Health, Canberra, accessed 10 January 2024.

Morgan VA, Waterreus A, Jablensky A, Mackinnon A, McGrath JJ, Carr V, Bush R, Castle D, Cohen M, Harvey C, Galletly C, Stain HJ, Neil AL, McGorry P, Hocking B, Shah S and Saw S (2011) People living with psychotic illness 2010: the second Australian national survey of psychosis, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(8), doi: 10.1177/0004867412449877, accessed 10 January 2024.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) (2023) Youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) (indicator), OECD, Paris, accessed 10 January 2024.

Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, Whiteford H, Burgess P, Pirkis J and Saw S (2009) The Mental Health of Australians 2. Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra, accessed 10 January 2024.

Whiteford H, Buckingham B, Harris M, Diminic S, Stockings E and Degenhardt L (2017) Estimating the number of adults with severe and persistent mental illness who have complex, multi-agency needs, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51(8):799-809, doi:10.1177/0004867416683814, accessed 10 January 2024.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2021) Comprehensive Mental health action plan 2013–2030, WHO, Geneva, accessed 10 January 2024.

Wilkins R, Laß I, Butterworth P and Vera-Toscano E (2019) The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 17 Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, University of Melbourne, accessed 10 January 2024.

This section was last updated 14 February 2024.