Aged care

Australia’s aged care system delivers services through a range of care types to cater for the diverse needs of the ageing population. Services range from supports to remain living largely independently at home, through to full-time care in a residential setting. Access to government-subsidised aged care services does not involve a minimum age of eligibility (with the exception of home support) – rather, access is determined based on assessed need. Although the majority of people using aged care services are aged 65 and over, younger people also access these services (AIHW 2023d).

This page explores the use of mainstream residential and community-based aged care programs by people aged 65 years and over. It provides information about how people are assessed for, and enter, aged care, the types of care they use, and how they leave aged care. It is important to note that a person may use multiple programs during the year, and may be counted more than once as an admission or exit. For more information on aged care in Australia, including younger people using aged care, see GEN aged care data.

Types of aged care

There are 3 mainstream types of care:

-

Residential aged care provides accommodation and care at a facility on a permanent or respite (temporary) basis. Permanent care is intended for those who can no longer live at home due to increased care needs, while respite provides a break from normal living arrangements.

- Home support (Commonwealth Home Support Programme) provides entry-level support at home for people as well as their carers. Services available through home support include domestic assistance, personal care, social support, allied health and respite services.

- Home care (Home Care Packages Program) provides different levels of aged care services for people in their own homes. It is targeted towards people with needs that go beyond what home support can provide. Ongoing services are available to keep people well and independent (such as nursing care), stay in their home (through help with cleaning, cooking and home maintenance) and remain connected to their community through transport and social support.

There are also several types of flexible care available that extend across the spectrum from home support to residential aged care, including:

- Transition care, which provides short-term care to restore independent living after a hospital stay.

- Short-term restorative care, which provides early intervention services to reduce difficulty with everyday tasks and maintain or restore independence.

- Multi-Purpose Services Program, which provides integrated health and aged care services in small regional and remote communities that cannot support both a separate aged care facility and a hospital.

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program, which delivers a mix of care types in a culturally appropriate way for older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- Department of Veterans’ Affairs community nursing and Veterans’ Home Care services for eligible veterans and their families, which provides support to help people stay in their own home.

Aged care assessments

To access government-funded aged care services, people undergo an assessment of need. These processes assess people’s circumstances and care needs and, where appropriate, approve them for particular aged care services. They also refer people to service providers.

My Aged Care is a contact centre and website which serves as the starting point for access to government-subsidised aged care services. Access to My Aged Care can be gained by self-referral, or requests from carers or health and aged care professionals.

Following an initial screening through the My Aged Care platform, people are directed to one of 2 types of assessment:

- Aged Care Assessment Teams (ACATs) conduct comprehensive assessments and approve people for entry into residential aged care (permanent or respite), home care and transition care programs.

- Regional Assessment Services assess eligibility for entry-level home support services, known as the Commonwealth Home Support Programme.

In 2021–22 there were around 273,000 home support assessments and 201,000 comprehensive assessments completed (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). The number of completed comprehensive aged care assessments increased by 13% between 2012–13 and 2021–22, however trends tend to fluctuate generally from year to year (SCRGSP 2023).

Entering aged care

The time between an individual’s ACAT approval and access to an aged care service can be influenced by a range of factors, including availability of places and packages of care, and a person’s individual preferences about entering care.

In 2021–22:

- 41% of new entrants to permanent residential care entered permanent care within 3 months of their ACAT assessment (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022)

- the median time elapsed for access to a Home Care Package ranged from 1 month for a Level 4 package, 5 months for a Level 1 package and 8 months for a Level 2 or Level 3 package (SCRGSP 2023).

In 2021–22, 245,000 people aged 65 and over entered residential care and home care. Around 3 in 5 (62%) admissions were for residential aged care, including approximately 68,400 for permanent care and 82,300 for respite care (AIHW 2023a).

Characteristics of people entering aged care in 2021–22 include:

- Over half (54%) of people aged 65 and over entering permanent residential aged care were aged 85 and over.

- Almost 3 in 5 (59%) people aged 65 and over entering permanent residential care for the first time were women. This proportion increased with age. This is partly driven by the fact that women’s life expectancy exceeds men’s, so there are more women than men at older ages entering and using aged care.

- Almost 2 in 5 (37%) people aged 65 and over entering home care were aged 85 and over (AIHW 2023a).

Of all people entering residential and home care in 2021–22, 1.0% were aged under 65 (AIHW 2023a).

People using aged care

People tend to use different aged care programs at different stages of their life. As people get older, it is likely they will experience escalating care needs that require different care types. However, people’s journey through aged care can vary. Some people may start using lower-level care services, then progress to using increasing levels of care as their needs change. For others, their first experience with aged care services may be when they require higher level care after a sudden event, such as the loss of a carer or a health crisis.

Home support

In 2021–22, around 800,000 people aged 65 and over used home support services. Of these:

- 2 in 3 (65%) were female

- the highest proportion of people were aged 80–84 (23%) (AIHW 2023d) (Figure 4.1).

In 2021–22, including people whose sex is unknown, 30% of people aged 65 and over using home support were aged 85 and over. This is lower than home care (41%) and residential aged care (59%).

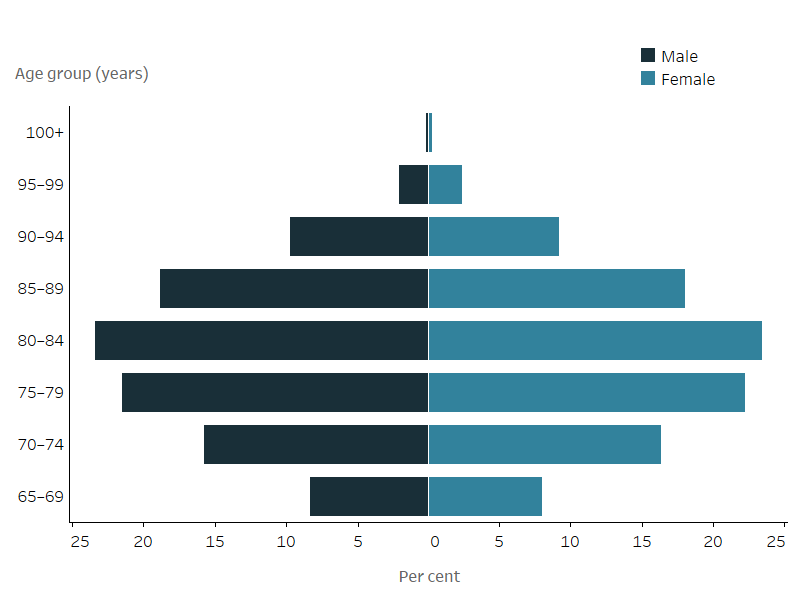

Figure 4.1 Home support recipients by age group and sex, 2021–22

Figure 4.1: Home support recipients by age group and sex, 2021–22

The butterfly chart shows that the highest percentage of people using home support were aged 80–84 years (approximately 23% of men and 23% women using home support were aged 80–84). The age distribution of home support use by Australians aged 65 years and over was similar among men and women.

Notes

- Excludes unknown age and sex.

- Proportions sum to 100% for males and females separately.

Source: AIHW 2023d – GEN aged care data.

Home care

At 30 June 2022, almost 213,000 people using home care were aged 65 and over. This is more than triple the 69,500 people aged 65 and over who were accessing home care services at 30 June 2017 (AIHW 2023d). The growth in home care follows the introduction of the Increasing Choice in Home Care reforms in February 2017 which changed the way home care services were delivered. Under these reforms, funding for home care packages were assigned to the recipient rather than the provider, giving recipients more choice and flexibility (Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

Levels of home care

Home care provides varying levels of care to individuals based on their assessed care needs. A coordinated package of care is available at 4 levels, from Level 1 (basic care – for example, shopping assistance, transportation, and meal preparation), through to Level 4 (high-level care – for example, assistance with bathing, dressing, and getting out of bed, including support for additional care needs such as dementia, or vision and hearing impairment).

At 30 June 2022, of all home care recipients:

- 5.4% were receiving care at Level 1

- 41% were receiving care at Level 2

- 31% were receiving care at Level 3

- 22% were receiving care at Level 4 (AIHW 2023d).

At 30 June 2022, of people aged 65 and over using home care (including where sex is unknown):

- 2 in 3 (65%) were women (139,000 people)

- the highest proportion were aged 85 and over (41%, 88,300 people) (Figure 4.2).

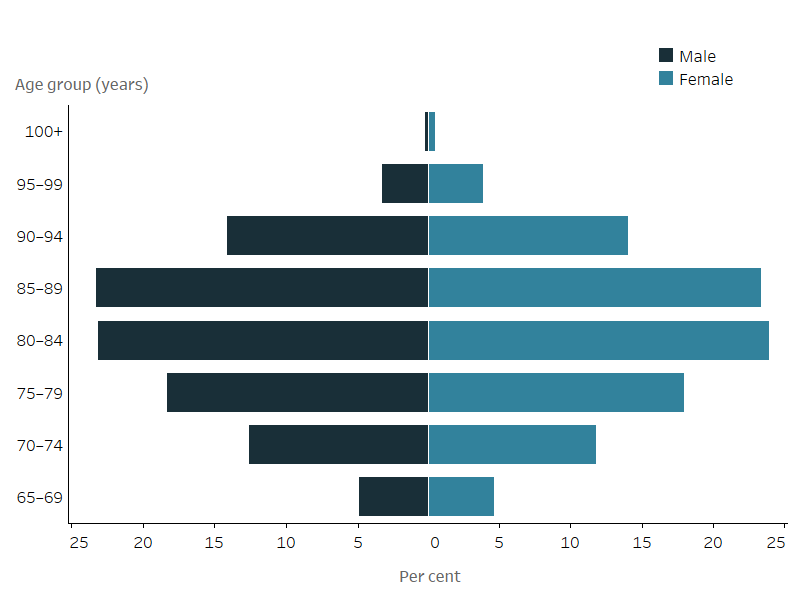

Figure 4.2 Home care recipients by age group and sex, 30 June 2022

Figure 4.2: Home care recipients by age group and sex, 30 June 2022

The butterfly chart shows that the highest percentage of people using home care were aged 80–84 and 85–89 years (46% of men and 47% of women using home care were aged 80–89 years). The age distribution of home care use by Australians aged 65 years and over was similar among men and women.

Notes

- Excludes unknown age and sex.

- Proportions sum to 100% for males and females separately.

Source: AIHW 2023d – GEN aged care data.

Residential aged care

At 30 June 2022:

- 185,000 people using residential care were aged 65 years and over, with:

- 178,000 living in permanent residential care

- 7,400 using respite care.

- Among people aged 65 and over in permanent residential care:

- the number of women was almost double the number of men

- people were most commonly aged 85–89 (Figure 4.3) (AIHW 2023d).

- The number of people aged 65 and over living in permanent residential aged care increased by 3.1% over the last 5 years (from 172,000 at 30 June 2017 to 178,000 at 30 June 2022) (AIHW 2023d). This change may be partially attributed to the growth in the Australian population aged 65 and over, which increased 17% over the same period (from 3.8 million to 4.4 million people) (ABS 2023).

Compared with other aged care programs, people generally use residential aged care at older ages. For all admissions to permanent residential aged care in 2021–22, the average age at admission was 83 years for men and 85 years for women (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022).

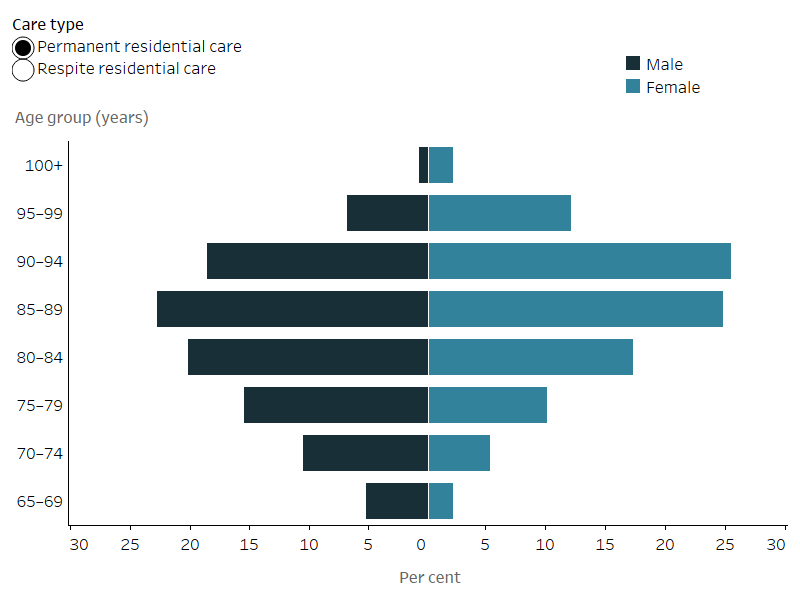

Figure 4.3 Residential aged care recipients by age group and sex, 30 June 2022

Figure 4.3: Residential aged care recipients by age group and sex, 30 June 2022

The butterfly chart shows that the highest percentage of men using permanent residential care were aged 85–89 years (23%), while among women, the age group with the highest percentage using permanent residential care was slightly older (26% of women using residential care were aged 90–94 years). The highest percentage of people using respite residential care were aged 85–89 years (approximately 25% of men and 27% of women using respite residential care were aged 85–89 years). The age distribution of permanent and respite residential care use among Australians aged 65 years and over differed by sex, with greater percentages of men in relatively younger age groups (65–84) using residential aged care compared with women.

Notes

- Excludes unknown age and sex.

- Proportions sum to 100% for males and females separately.

Source: AIHW 2023d – GEN aged care data.

Impact of COVID-19 on older people in aged care

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the health and wellbeing of people using aged care, particularly those in residential aged care. Compared to the general community, people in residential aged care were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 infection in terms of risk of serious illness and related mortality (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a). Three-quarters (75%) of all COVID-19 related deaths in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (to 5 March 2021) were among people living in residential aged care (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b).

The 2021–22 financial year saw an increased COVID-19 case load on the aged care sector. Most of Australia’s residential aged care homes experienced a COVID-19 outbreak during 2021–22 (2,570 facilities experienced one or more outbreaks in 2021–22). During the 12-month period, there were over 56,000 resident cases and almost 2,200 resident deaths in aged care (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). As at 30 June 2022, 29% of all COVID-19 related deaths in Australia were among people living in residential aged care (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b).

Across all types of aged care, the lockdowns and social restrictions may have affected access to formal and informal support. For example, older people living in the community were encouraged to seek health services remotely through telehealth, and a number of temporary Medicare items were added. Additionally, measures introduced in the aged care sector meant that people in residential aged care could temporarily return to community-living through ‘emergency leave’ that provided up to eight weeks of home support.

The restrictions imposed may also have affected people’s physical, mental and emotional wellbeing. The isolation and social disconnection experienced by permanent residential aged care residents as a result of visitor restrictions and lockdowns at many facilities, placed older people at greater risk of health problems including anxiety and neurocognitive conditions.

Assessment of care needs

Until recently, the Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) has been used to assess the care needs of people living in permanent residential aged care to determine the government funding provided to care providers. Residents may be reappraised in the same year if their needs change. The ACFI measures care needs across 3 different areas of care:

- activities of daily living

- cognition and behaviour

- complex health care.

On 30 June 2022, among people aged 65 and over living in permanent residential aged care, almost 2 in 5 (37%) had high care ratings across all 3 ACFI assessment areas (AIHW 2023b).

Australian National Aged Care Classification

On 1 October 2022, the Australian National Aged Care Classification (AN-ACC) residential care funding model replaced the ACFI. The AN-ACC Assessment Tool focuses on the characteristics of residents that drive care costs in residential care. AN-ACC data are not currently reported on this page.

For more information about AN-ACC, see the AN-ACC Reference Manual and AN-ACC Assessment Tool on the Department of Health and Aged Care website.

Health of people in aged care

People using aged care continue to interact with the health system through General Practitioners (GPs), specialists and the hospital system. For example, GPs are an important part of the health care of people living in residential aged care. Among people living in permanent residential aged care in 2016–17, some 92% had at least one Medicare Benefits Scheme claim for a GP visit, and almost all of the remaining would have seen a doctor through some other interface with the health or aged care system, such as hospitals or through Department of Veterans’ Affairs arrangements (AIHW 2020).

For more information on use of health services, see the Health – service use chapter.

Leaving aged care

Many people use aged care in their final years of life. For deaths among people aged 50 and over in 2016–17, over two thirds (67%) had used at least one aged care service in the last 2 years of life. For people over the age of 85 in 2016–17, 50% of deaths were in residential care, compared with 40% in hospital (AIHW 2021).

People may also leave care to move back home, to enter other aged care, or to be admitted to hospital. The following information covers exits from aged care services in 2021–22. A person may be counted twice if they exited aged care services more than once over the 12-month period.

In 2021–22, for people aged 65 years and over:

- there were almost 201,000 exits from residential aged care and home care

- the majority of exits were by people leaving respite residential care (82,000, 41%), followed by permanent residential care (71,200, 35%) and home care (47,700, 24%)

- most (86%) exits from permanent residential care were due to death, compared with 38% from home care. The majority of exits from home care were to residential care (51%).

Of all people who exited permanent residential aged care, those who died in care had the longest median length of stay (approximately 25 months) (AIHW 2023c).

Among people aged 65 and over exiting aged care, those in permanent residential care had the longest median length of stay (22 months), followed by home care (17 months) and respite residential care (21 days). Women stayed longer in permanent residential care than men, while this difference was less pronounced in respite care.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on Australians’ use of aged care services, see the AIHW's aged care data website, GEN aged care data.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2023) National, state and territory population, ABS, accessed May 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2020) Interfaces between the aged care and health systems in Australia—GP use by people living in permanent residential aged care 2012–13 to 2016–17, AIHW, accessed April 2023.

AIHW (2021) Interfaces between aged care and health systems in Australia—where do older Australians die?, AIHW, accessed April 2023.

AIHW (2023a) GEN Aged Care Data: Admissions into aged care, AIHW, accessed June 2023.

AIHW (2023b) GEN Aged Care Data: Care needs of people in aged care, AIHW, accessed June 2023.

AIHW (2023c) GEN Aged Care Data: People leaving aged care, AIHW, accessed June 2023.

AIHW (2023d) GEN Aged Care Data: People using aged care, AIHW, accessed April 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) Home Care Packages Program reforms, Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed May 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2022) 2021–22 Report on the operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed April 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023a) COVID-19 advice for older people and carers, Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed May 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023b) COVID-19 outbreaks in Australian residential aged care facilities, Department of Health and Aged Care, accessed March 2023.

SCRGSP (Steering Committee Report on Government Service Provision) (2023) Report on Government Services 2023. Part F. Community Services Section 14, Productivity Commission, accessed March 2023.