Aged care for First Nations people

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Aged care for First Nations people, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Aged care for First Nations people. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/aged-care-for-indigenous-australians

MLA

Aged care for First Nations people. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/aged-care-for-indigenous-australians

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aged care for First Nations people [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/aged-care-for-indigenous-australians

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Aged care for First Nations people, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/aged-care-for-indigenous-australians

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

The population of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people has a much younger age structure (see glossary) than the non-Indigenous population (see Profile of First Nations people). However, like the general population, the First Nations population is ageing.

Access to aged care services (see glossary) in Australia is determined by need, rather than age. However, the target population for government-funded aged care services is the First Nations population aged 50 and over and the non-Indigenous population aged 65 and over (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). A broader age group is used for First Nations people because of their greater need for care at a younger age compared with non-Indigenous Australians.

This page focuses on First Nations people aged 50 and over and their use of aged care services. Throughout this page, the age of the person receiving aged care is calculated as of 30 June of the relevant financial year. For more information regarding use of aged care services, particularly among the general population, see Aged care, and ‘Chapter 8 Measuring quality in aged care: what is known now and what data are coming’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights.

First Nations people aged 50 and over

Preliminary Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates indicate that there were around 174,000 First Nations people aged 50 and over on 30 June 2021 (AIHW analysis of ABS 2022a). This included about:

- 120,200 aged 50–64

- 50,500 aged 65–84

- 2,900 aged 85 and over.

First Nations people aged 50 and over comprised:

- 18% of the First Nations population (of all ages)

- 1.9% of the total Australian population aged 50 and over.

Use of aged care services by First Nations people

Data on the use of aged care by First Nations people are sourced from the Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse, made readily available on the GEN aged care data website. The main types of government-subsidised aged care are home support, home care, and residential aged care (see glossary). In some cases, these aged care services are provided as part of a separate program, such as one of the flexible aged care (see glossary) programs. For the purposes of this page, the quoted numbers of home support, home care and residential care recipients do not include recipients who received these services as part of a flexible aged care program. Among First Nations people aged 50 and over:

- 22,100 (14%) received home support during 2021–22. This is entry-level support provided through the Commonwealth Home Support Programme (see glossary), aimed at helping people manage independently at home for as long as possible

- 5,800 (3.6%) were receiving home care at 30 June 2022. This is a coordinated package of care and services, from basic through to high-level support, based on need, provided through the Home Care Packages Program (see glossary)

- 2,100 (1.3%) were receiving residential aged care at 30 June 2022. This means staying in a residential aged care facility, on a permanent or temporary basis.

Included in the numbers above are respite care (see glossary) users, who receive care through home support or residential care, depending on the need of the user.

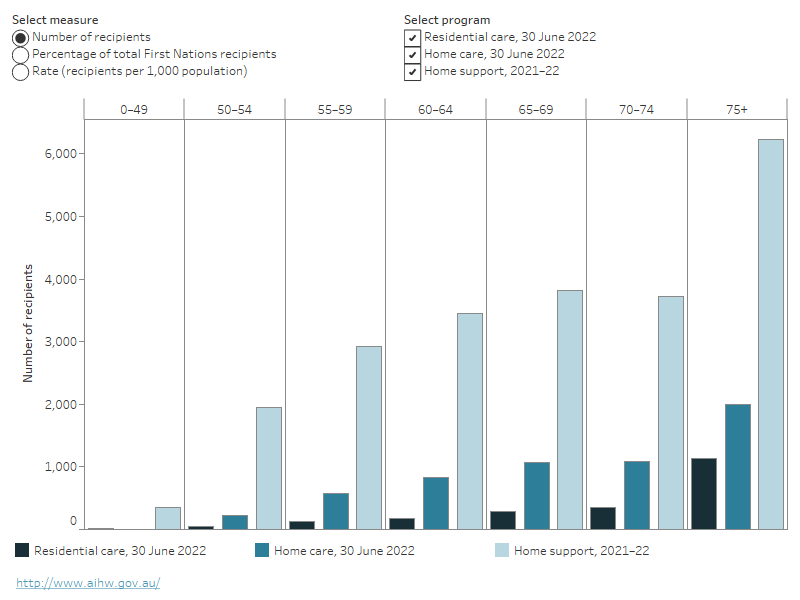

First Nations people using residential aged care tended to be older than those using home care or home support (Figure 1). For example, over half (53%) of the First Nations people in residential aged care were aged 75 and over. The same age group made up around one-third (35%) of all First Nations home care clients, and 28% of First Nations home support users.

Indigenous status (referring to whether a person has identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin) was not stated for more than 1 in 6 (36,500, or 17%) of home care recipients at 30 June 2022 – greatly exceeding the number of First Nations home care recipients – so home care data should be interpreted with caution.

Flexible care services constitute, for the purposes of this page, a separate set of aged care services, in which care is provided for special groups or in circumstances where the above mentioned services are not appropriate. For example, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program provides culturally appropriate flexible care for First Nations people in locations close to their communities. On 30 June 2022, this program had funding for a total of 1,310 places across home care and residential aged care. The Multi-Purpose Services Program also funds flexible care services in many rural and remote areas. Among those who received Multi-Purpose Services care in 2021–22, 196 identified as First Nations people (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b).

Figure 1: Use of aged care by First Nations people for selected programs, by age group and program

This interactive bar chart shows the number, proportion, and rate of First Nations people using home support, home care, and residential aged care, by age group. On 30 June 2022, 53% of First Nations people using residential aged care and 35% of First Nations home care recipients were aged 75 and over. In 2021–22, 28% of First Nations people using home support were aged 75 and over. First Nations people under 50 made up less than 2% across each of the three aged care types.

Notes

- Rates of First Nations people are calculated using ABS 2016 Census-based population projections (Series B) (ABS 2023).

- First Nations people refers to people who have identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Data exclude recipients whose Indigenous status and/or age was not stated or inadequately described.

Sources: AIHW National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse; AIHW analysis of ABS (2023).

Variation by remoteness

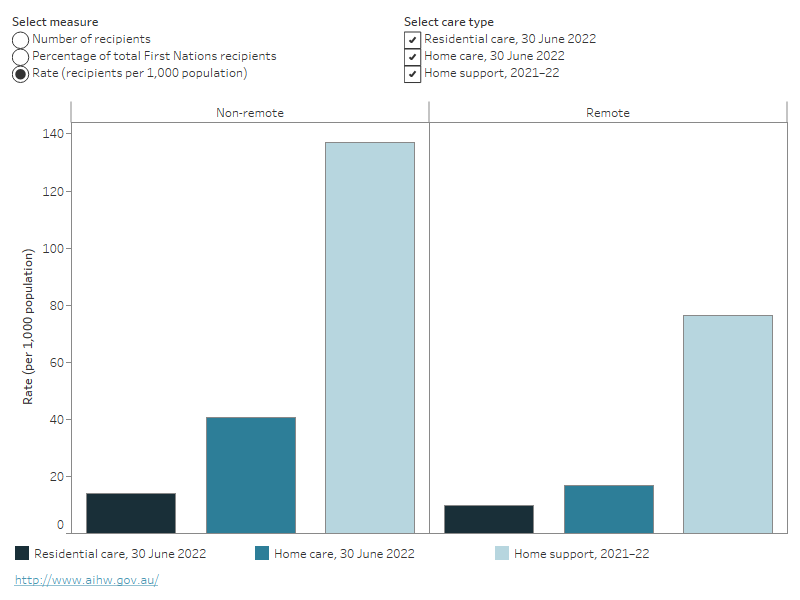

Among First Nations people aged 50 and over who used home support in 2021–22 or who received home care or residential aged care on 30 June 2022, most lived in non-remote areas (Figure 2). This is consistent with the fact that a higher number of First Nations people live in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner regional or Outer regional areas) than in remote areas (Remote or Very remote areas).

Considering the rate of aged care service use per population, among First Nations people aged 50 and over:

- Those living in non-remote areas were 1.8 times more likely to receive home support services than those living in remote areas in 2021–22.

- Those living in non-remote areas were 2.4 times more likely to receive home care services than those living in remote areas on 30 June 2022.

- Those living in non-remote areas were 1.4 times more likely to receive residential aged care services than those living in remote areas on 30 June 2022.

Figure 2: Variation in use of selected aged care programs by First Nations people aged 50 and over, by remoteness area and program

This interactive bar chart shows the number, proportion, and rate of First Nations people using home support, home care, and residential aged care, by remoteness area. The rate of recipients per population is higher among First Nations people living in non-remote areas compared to those living in remote areas across all three aged care types.

Notes

- Rates of First Nations people are calculated using ABS 2016 Census-based population projections (Series B) (ABS 2023).

- First Nations people refers to people who have identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Data exclude recipients whose Indigenous status, age and/or remoteness area was not stated or inadequately described.

Sources: AIHW National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse; AIHW analysis of ABS (2023).

Comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

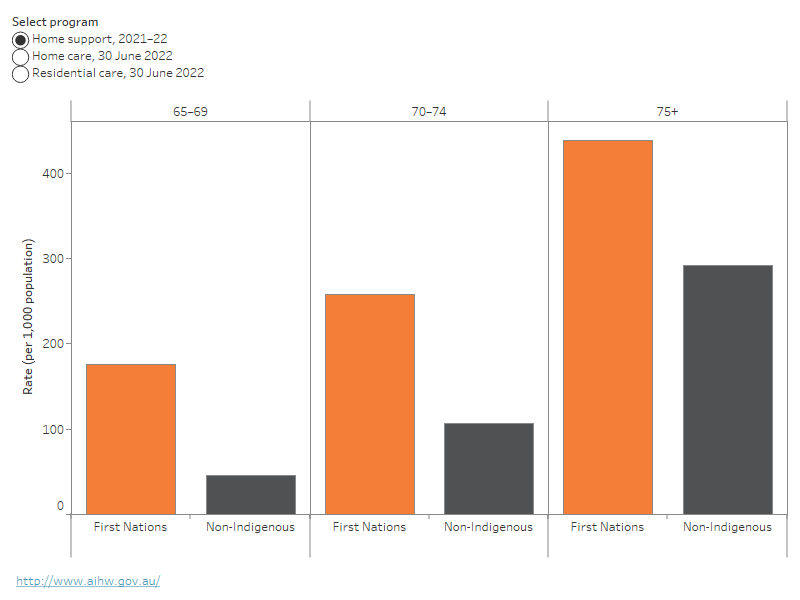

Except for use of residential aged care among people aged 75 and over, rates of aged care use were higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians across all age groups and care types (Figure 3).

Among people aged 65–74, compared with the rate among non-Indigenous Australians, First Nations people were:

- 2.8 times more likely to use home support in 2021–22 (7,500 First Nations recipients, receiving care at a rate of 209 per 1,000 population, and 178,000 non-Indigenous recipients, receiving care at a rate of 74 per 1,000 population)

- 5.3 times more likely to use home care, as at 30 June 2022 (2,100 First Nations recipients, receiving care at a rate of 60 per 1,000 population, and 27,200 non-Indigenous recipients, receiving care at a rate of 11 per 1,000 population)

- 2.3 times more likely to use residential aged care, as at 30 June 2022 (640 First Nations recipients, receiving care at a rate of 18 per 1,000 population, and 18,600 non-Indigenous recipients, receiving care at a rate of 8 per 1,000 population).

Figure 3: Rate of aged care use (per 1,000 population) among persons aged 65 and over in selected programs, by age group and Indigenous status

This interactive bar chart shows the rate of First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians using home support, home care, and residential aged care, by age group. The rate of aged care use per 1,000 population was higher among First Nations people across all age groups and aged care types, except for residential aged care among those aged 75 and over. The group with the highest rate of service use per population was First Nations people aged 75 and over using home support, with 414.3 per 1,000 population using this type of aged care support.

Notes

- Rates of First Nations people are calculated using ABS 2016 Census-based population projections (Series B) (ABS 2023). Non-Indigenous rates are calculated using ABS ERP calculations (ABS 2022b), subtracted by First Nations population projections for the same time.

- First Nations people refers to people who have identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Data exclude recipients whose Indigenous status and/or age was not stated or inadequately described.

Sources: AIHW National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse; AIHW analysis of ABS (2022b, 2023).

Changes over time

Over the past few years, home support has been delivered through the Commonwealth Home Support Programme. Prior to 1 July 2018, home support was (partially) delivered through the Home and Community Care program, after a gradual rollout which started 1 July 2015. Overall, the number of First Nations home support recipients has increased since 5 years ago, however, due to a relatively stronger increase in the population size of First Nations people aged 50 and over, the rate of home support service use per population has decreased – from 149 to 138 recipients per 1,000 population between 2017–18 and 2021–22 (Table 1).

| Time period | First Nations people | Non-Indigenous Australians | Rate of First Nations people (per 1,000) | Rate of non-Indigenous Australians (per 1,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 20,200 | 705,429 | 149.3 | 86.1 |

| 2018–19 | 21,337 | 759,552 | 151.3 | 90.7 |

| 2019–20 | 21,791 | 774,375 | 131.7 | 90.1 |

| 2020–21 | 22,210 | 763,755 | 145.8 | 86.9 |

| 2021–22 | 22,095 | 761,259 | 138.1 | 85.0 |

Notes

- Rates of First Nations people are calculated using ABS 2016 Census-based population projections (Series B) (ABS 2023). Non-Indigenous rates are calculated using ABS ERP calculations (ABS 2022b), subtracted by First Nations population projections for the same time.

- Indigenous status refers to whether a person has identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Data exclude persons for whom Indigenous status and/or age was not stated or inadequately described. In 2017–18 Indigenous status was lacking for 6.7% recipients, 6.6% in 2018–19, 4.9% in 2019–20, 4.5% in 2020–21, and 4.0% in 2021–22.

- Dates that home support providers input can reflect dates of data submission rather than dates of service use.

Sources: AIHW National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse; AIHW analysis of ABS (2022b, 2023).

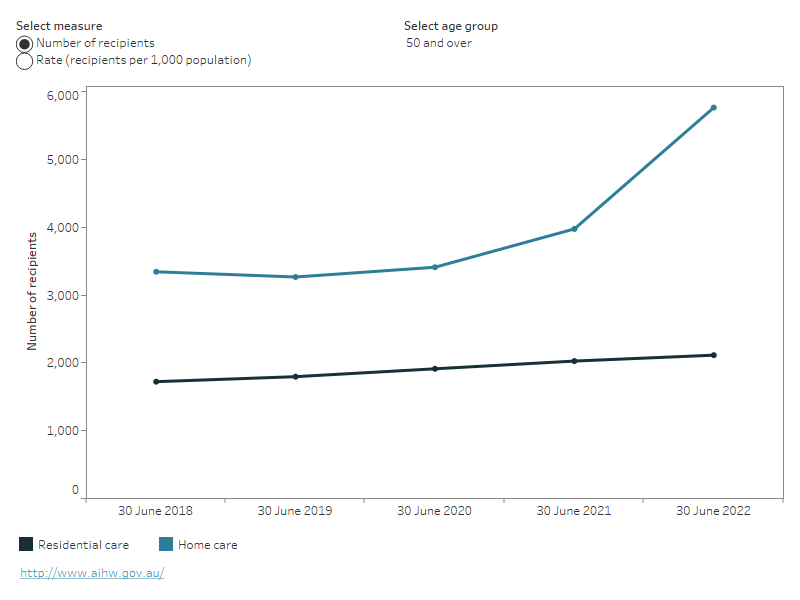

Between 30 June 2018 and 30 June 2022, the rate of home care use for First Nations people aged 50 and over increased from 25 to 36 per 1,000, with numbers increasing from 3,300 to 5,800 (Figure 4). The trend over the past 5 years has varied between the different age groups – with some age groups seeing lower home care numbers in the years between 2018 and 2022, and others steadily increasing each year.

Between 30 June 2018 and 30 June 2022, the number of First Nations people aged 50 and over in residential aged care rose from 1,700 to 2,100 (Figure 4). It is worth noting that the rate and number of First Nations people using residential aged care services has only risen for those aged 65 and over. For First Nations people aged 50–64, the number and rate of residential aged care use has declined over the same period.

Figure 4: Residential aged care and home care use by First Nations people aged 50 and over, by age group and age care type, 30 June 2018 to 30 June 2022

This interactive line chart shows that, among First Nations people aged 50 and over, the overall number of home care recipients have increased from 3,344 to 5,766 recipients between 30 June 2018 to 30 June 2022. Over the same period, the number of residential care recipients has increased from 1,723 to 2,114. The rate of aged care use has varied over this time span and differs between the age groups.

Notes

- Rates of First Nations people are calculated using ABS 2016 Census-based population projections (Series B) (ABS 2023).

- First Nations people refers to people who have identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Data exclude recipients whose Indigenous status and/or age was not stated or inadequately described.

- In the home care data, the Indigenous status is unknown for 17% of the recipients on 30 June 2022, 36% on 30 June 2021, 36% on 30 June 2020, 18% on 30 June 2019, and 1.2% on 30 June 2018. As a result, the number of recipients and rate of use presented here may not be representative of true service use.

- The way service use is captured, and how this is reflected in the dates of use, vary between the aged care programs. For example, dates registered by home support providers may reflect dates of data submission rather than dates of service use.

Sources: AIHW National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse; AIHW analysis of ABS (2023).

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flexible Aged Care Program was expanded between 2018–19 and 2021–22 (Department of Health 2018b). Between 30 June 2018 and 30 June 2022, the program grew by more than 50% (an increase of 450 places) from 860 to 1310 (Table 2).

Date | Residential care places | Home care places | Total number of places |

|---|---|---|---|

30 June 2018 | 489 | 371 | 860 |

30 June 2019 | 474 | 598 | 1,072 |

30 June 2020 | 494 | 770 | 1,264 |

30 June 2021 | 480 | 824 | 1,304 |

30 June 2022 | 475 | 835 | 1,310 |

Sources: Department of Health 2018a, 2019a, 2020a, 2021a; Department of Health and Aged Care 2022.

The impact of COVID-19

In March 2020, measures to reduce the risk of community transmission of COVID-19, including limiting public gatherings and reducing non-essential travel, were put in place across Australia (Campbell and Vines 2021). The reduction of non-essential travel included restrictions on travel to and between remote and very remote communities (Department of Health 2020b), which potentially affected the use of aged care services in those areas. Additionally, provisions for aged care providers were included in jurisdictional public health orders – with changes including the restriction of visits to and from residential aged care facilities – however, the details differed across states and territories, and across individual facilities.

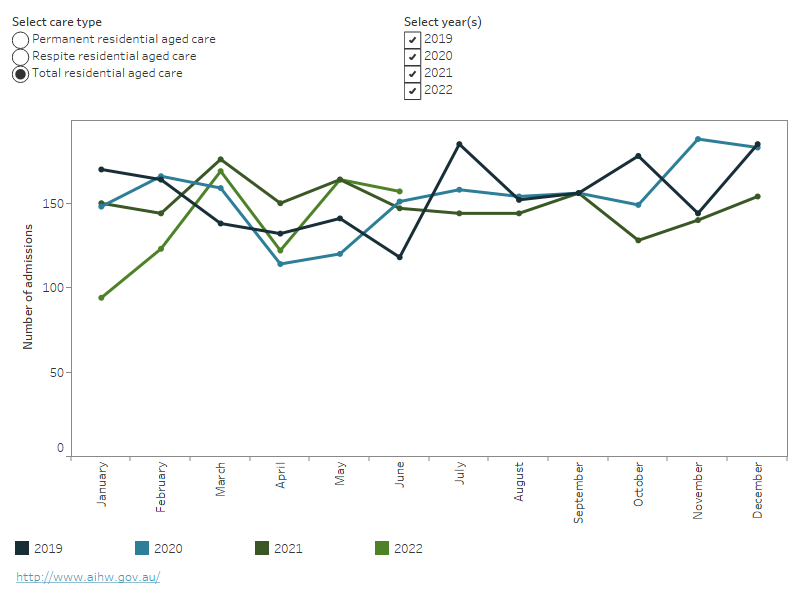

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated changes to aged care services may have influenced First Nations people’s patterns of accessing aged care. A potential impact of COVID-19 can be seen in the lowered number of admissions of First Nations people to respite residential aged care in April and May 2020 (Figure 5), when many COVID-19 related restrictions were first put in place in Australia. Similarly, the lowest monthly admission numbers during 2021 were seen in October, when COVID-19 related deaths due to the Delta variant were at their highest (AIHW 2022). The lowest number of residential aged care admissions seen in any month between the start of 2019 and mid-2022 occurred in January 2022, when COVID-19 confirmed case numbers and deaths were at their highest so far during the first outbreak of the Omicron variant following the winding back of COVID-19 restrictions nationwide (AIHW 2022).

It should be noted that admission numbers include both new admissions and movements between facilities.

Figure 5: Admissions of First Nations people into residential aged care for selected programs, by aged care type and month, 2019 to 2022

This interactive line chart shows monthly admissions to residential aged care among Fist Nations people between January 2019 and June 2022. The number of admissions has varied over time, with the lowest total number of admissions being 94 admissions in January 2022.

Notes

- First Nations people refers to people who have identified as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Data exclude admissions where Indigenous status was not stated or inadequately described.

- Respite residential aged care is when dependent people living in the community are temporarily admitted into residential aged care, giving people – or their carers – a short break from their usual care arrangements.

- Permanent residential aged care is when a person is admitted into long-term residential aged care, making it their ongoing place of residence.

- The fluctuations in admissions could reflect a number of factors that may or may not be related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: AIHW National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse.

See Aged care for information on the impacts of COVID-19 on aged care use in the general population.

Aged care for First Nations people

In Australia, the aged care system offers options to meet the care needs of individuals. To help ensure aged care services are appropriate to the diverse needs of all people, the Aged Care Act 1997 highlights the breadth of service needs by specifying some groups of people as ‘people with special needs’. First Nations people are one such group (Aged Care Act 1997: s11–3).

In the context of First Nations people, challenges for the aged care system include ensuring access to culturally appropriate care, especially for those living in remote and very remote areas (ANAO 2017). In 2019, the Australian Government published Actions to support older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, developed under the Aged Care Diversity Framework. These outline actions to support more inclusive and culturally appropriate care for First Nations people (Department of Health 2019b).

The Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (Royal Commission) has also identified areas of importance in providing aged care to First Nations people.

In its Final Report, the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety identified that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have specific needs when accessing aged care. The report makes several recommendations, covering topics such as:

- the importance of culturally appropriate and safe care – including growing the First Nations aged care workforce through targeted programs and providing interpreter services for First Nations languages

- the requirement for trauma-informed approaches to providing care, particularly with members of the Stolen Generations

- the need to increase facilitation of provision of care on Country (or with options to return to Country where this is not possible)

- the potential to integrate aged care with existing First Nations organisations such as healthcare providers, disability services and social service providers (RCACQS 2021).

In response to the Royal Commission, the Australian Government promised $572.5 million to ensure First Nations people can receive quality, culturally safe aged care, can access advice to make informed decisions about their care, and will be treated with dignity and respect (Department of Health 2021b).

The AIHW have also partnered with the Department of Health and Aged Care to work on the development of a National Aged Care Data Strategy, a National Minimum Data Set and a National Aged Care Data Asset. This will improve the available data on aged care – including with respect to First Nations recipients (for more information, see the data improvements on GEN aged care data).

A new aged care Act to replace and improve upon the Aged Care Act 1997 and the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission Act 2018 is currently under development, with this work being undertaken by the Department of Health and Aged Care in consultation with a range of stakeholders (Department of Health 2021c; Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on First Nations people aged 50 and over and aged care use among the First Nations population, see:

- Insights into vulnerabilities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 50 and over

- Regional Insights for Indigenous Communities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 50 and over

- AIHW’s dedicated aged care data website – GEN aged care data; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people using aged care dashboard.

Visit Aged care and First Nations people for broader information on each of the topics.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2022a) Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, AIHW analysis of data downloads, accessed 27 March 2023.

ABS (2022b) National, state and territory population, June 2022, AIHW analysis of data downloads, accessed 16 December 2022.

ABS (2023) Projected population, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, Remoteness Area, 2016 to 2031 [Data Explorer], explore.data.abs.gov.au, accessed 28 November 2022.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022) Australia’s health 2022: data insights, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 28 November 2022. doi:10.25816/ggvz-vr80

ANAO (Australian National Audit Office) (2017) Indigenous aged care, ANAO, Australian Government, accessed 22 November 2022.

Campbell K and Vines E (2021) COVID-19: a chronology of Australian Government announcements (up until 30 June 2020), Research Paper Series, 2020–21, Parliamentary Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Australian Government, accessed 26 June 2023.

Department of Health (2018a) 2017–18 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 14 November 2022.

Department of Health (2018b) Health Portfolio Budget Statements 2018–19, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 28 November 2022.

Department of Health (2019a) 2018–19 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 14 November 2022.

Department of Health (2019b) Actions to support older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a Guide for Aged Care Providers, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 27 February 2019.

Department of Health (2020a) 2019–20 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 14 November 2022.

Department of Health (2020b) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19 communique – 31 March 2020, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 3 May 2023.

Department of Health (2021a) 2020–21 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 14 November 2022.

Department of Health (2021b) Aged care – Reforms to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 21 November 2022.

Department of Health (2021c) Governance (Pillar 5 of the Royal Commission response) – A new Aged Care Act, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 24 November 2022.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2022) 2021–22 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 1 December 2022.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023a) Aged care legislative reform, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 27 March 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023b) Fact Sheet: Multi-Purpose Services Program, GEN website, accessed 15 May 2023.

RCACQS (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety) (2021) Final Report -Volume 1: Summary and recommendations, RCACQS, Australian Government, accessed 5 July 2023.