Specialised support and informal care for First Nations people with disability

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Specialised support and informal care for First Nations people with disability, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 October 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Specialised support and informal care for First Nations people with disability. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/disability-support-for-indigenous-australians

MLA

Specialised support and informal care for First Nations people with disability. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/disability-support-for-indigenous-australians

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Specialised support and informal care for First Nations people with disability [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Oct. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/disability-support-for-indigenous-australians

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Specialised support and informal care for First Nations people with disability, viewed 27 October 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/disability-support-for-indigenous-australians

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

People with disability may need help with daily activities – for example, eating, showering, or moving around. They may also need help to participate in social and economic life. To do so, people with disability may use a range of formal support services and informal care.

In recent years, there have been several policy initiatives relating to disability that impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people.

Disability policy environment

The disability policy environment has significantly changed in recent years, especially in relation to service delivery, including:

- the launch of the new Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021–2031, which included engagement with Indigenous Australians with disability and an associated action plan which outlines actions to improve community attitudes towards people with disability

- the implementation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme, which includes the co-designing of a new First Nations Strategy and action plan

- the establishment of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission

- pilot-testing of the National Disability Data Asset

- the establishment of a Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability

- changing community attitudes and improving awareness of disability.

Disability prevalence

There are currently 3 main sources of data on First Nations people with disability (see ABS 2019a for more information). These are the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS):

- Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) – the SDAC uses the most comprehensive method to determine disability status and severity but it was not specifically designed to collect data about First Nations people and it also has limited coverage of smaller geographies and populations. In particular, it excludes First Nations people from Very remote areas and discrete First Nations communities.

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) – the NATSIHS uses the summarised Short Disability Module (which is not as detailed as the method used in SDAC) to determine disability status and severity but it was designed to generate results that are representative for First Nations people. It includes non-remote areas, remote areas and discrete First Nations communities.

- Census of Population and Housing (Census) – the scope of the Census is very large but it collects limited information on disability. Rather than being a broad measure of people with disability, it only captures people with more severe forms of disability (referred to as ‘needing assistance with core activities’ and equivalent to severe or profound disability as collected in the SDAC and the NATSIHS). Census data presented on this page excludes ‘not stated’ responses and may differ from that published elsewhere.

While each data source has different purposes and methodologies for capturing disability, and their estimates of overall disability among First Nations people vary, their estimates of severe or profound disability are broadly similar (ABS 2019a):

- The 2018 SDAC estimated that:

- 24% of First Nations people were living with disability (or around 140,000 out of 581,000), similar to the proportion in 2015

- 8.8% (51,100) of First Nations people were living with severe or profound disability, compared with 7.3% in 2015

- based on age-standardised rates, First Nations people were 1.9 times as likely to be living with disability as non-Indigenous Australians (ABS 2021).

- The 2018–19 NATSIHS estimated that:

- 38% of First Nations people were living with disability (306,100 out of 814,000) (ABS 2019b)

- 8.1% (66,100) of First Nations people were living with severe or profound disability (ABS 2019b)

- based on age-standardised rates, First Nations people were 1.5 times as likely to be living with disability as non-Indigenous Australians, and 2.5 times as likely to be living with severe or profound disability (AIHW and NIAA 2022).

- The 2021 Census estimated that 8.6% (66,400 out of 813,000) of First Nations people needed assistance with core activities (ABS 2022a). This was an increase from 7.2% in 2016 and 5.8% in 2011 (ABS 2011; ABS 2016).

Despite these differences, the data consistently indicate that for First Nations people (Tables 1 and 2):

- rates of disability are generally similar for males and females

- those aged 55 and over are more likely to experience disability than those aged under 55

- rates of overall disability are highest in Inner regional areas.

| 2018 SDAC | 2018–19 NATSIHS | |

|---|---|---|

| With disability

| 24.0 | 37.6 |

Aged 55 and over | 53.5 | 74.6 |

Aged under 55 | 19.4 | 32.5 |

| Male | 23.7 | 38.7 |

| Female | 24.3 | 36.5 |

| Major cities | 23.8 | 37.1 |

Inner regional areas | 29.6 | 40.3 |

Outer regional areas | 22.0 | 35.7 |

Remote areas | 18.1 | 37.4 |

Very remote areas | n.a. | 35.9 |

(a) Each data source has different purposes and methodologies for capturing information about disability, and therefore their estimates of disability vary.

Sources: ABS 2019b, 2021.

| 2018 SDAC | 2018–19 NATSIHS | 2021 Census(b) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aged 55 and over | 17.9 | 18.6 | 21.3 |

| Aged under 55 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 6.6 |

| Male | 8.5 | 8.6 | 9.3 |

| Female | 9.7 | 7.6 | 7.9 |

Major cities | n.a. | 9.6 | 9.3 |

Inner regional areas | n.a. | 8.5 | 9.7 |

Outer regional areas | n.a. | 7.3 | 8.2 |

Remote areas | n.a. | 6.6 | 5.9 |

Very remote areas | n.a. | 5.3 | 4.3 |

(a) Each data source has different purposes and methodologies for capturing information about disability, and therefore their estimates of disability vary.

(b) For the Census, ‘severe or profound disability’ refers to ‘needed assistance with core activities’. Calculations exclude ‘not stated’ need for assistance.

Sources: ABS 2019c, 2021, 2022b.

Education and employment

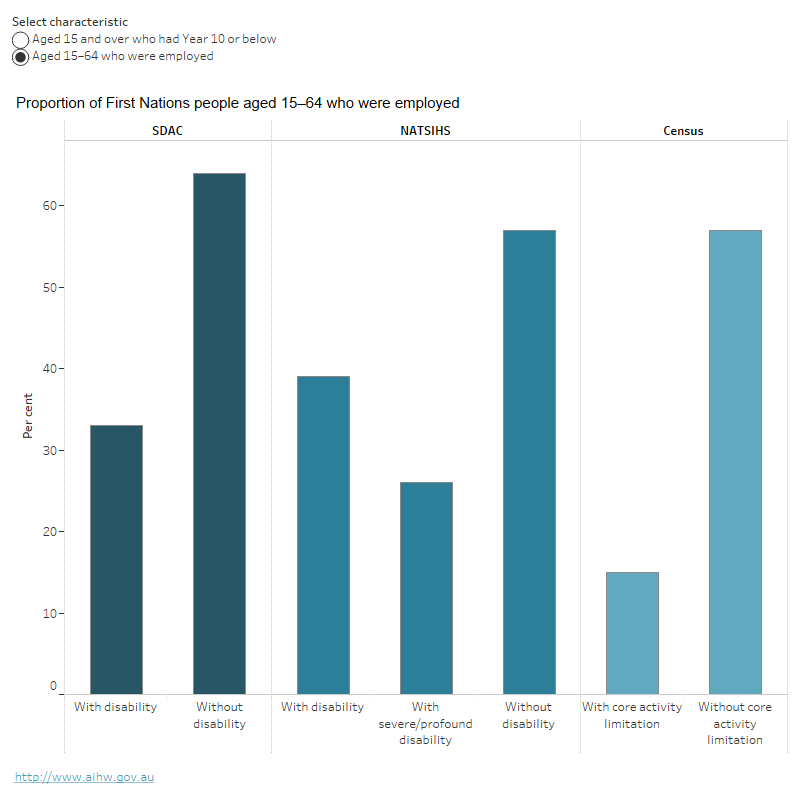

Disability can affect participation in education and in the labour force (Figure 1). According to the 3 main sources of data on First Nations people with disability, compared with First Nations people without disability:

- First Nations people with disability aged 15 and over were more likely to have Year 10 or below as their highest level of education:

- The 2018 SDAC estimated that 45% (47,400) of First Nations people aged 15 and over with disability had Year 10 or below as their highest level of education, compared with 30% (81,300) of First Nations people aged 15 and over without disability (ABS 2021). This was similar to 2015 when 46% (46,900) of First Nations people with disability in this age group had Year 10 or below as their highest level of education (ABS 2021).

- The 2018–19 NATSIHS estimated that 43% (103,300) of First Nations people aged 15 and over with disability and 46% (20,400) of First Nations people aged 15 and over with severe or profound disability had Year 10 or below as their highest level of education, compared with 36% (or 100,200) of First Nations people aged 15 and over without disability (ABS 2019b).

- The 2021 Census estimated that 54% (23,900) of First Nations people aged 15 and over who needed assistance with core activities had Year 10 or below as their highest level of education, compared with 34% (150,000) of First Nations people aged 15 and over who did not need assistance with core activities (ABS 2022b).

- First Nations people with disability aged 15–64 were less likely to be employed:

- The 2018 SDAC estimated that 33% (27,400) of First Nations people aged 15–64 with disability were employed, compared with 64% (166,100) of First Nations people aged 15–64 without disability (ABS 2021).

- The 2018–19 NATSIHS estimated that 39% (84,600) of First Nations people aged 15–64 with disability and 26% (10,500) of First Nations people aged 15–64 with severe or profound disability were employed, compared with 57% (159,000) of First Nations people aged 15–64 without disability (ABS 2019b).

- The 2021 Census estimated that 15% (5,170) of First Nations people aged 15–64 who needed assistance with core activities were employed, compared with 57% (246,000) of First Nations people aged 15–64 who did not need assistance with core activities (ABS 2022b).

Figure 1: Education and employment among First Nations people, by disability status and data source

This chart shows that, in all 3 data sources (SDAC, NATSIHS and Census), First Nations people with disability aged 15 and over were more likely to have Year 10 or below as their highest level of education compared with those without disability. It also shows that a lower proportion of First Nations people aged 15–64 with disability were employed compared with those without disability.

Notes

- Each data source has different purposes and methodologies for capturing information about disability, and therefore their estimates of disability vary.

- Census calculations exclude ‘not stated’ need for assistance.

Sources: ABS 2019b, 2021, 2022b.

Formal disability support

Specialist disability support services

Specialist disability support services assist people with disability to participate fully in all aspects of everyday life. Specialist disability support services in Australia are now largely provided through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) but there are also a range of other government and mainstream services that support First Nations people with disability. For more information on disability support services, see Specialised supports for people with disability.

Data sources for specialist disability support services

Data for specialist disability support services provided through the NDIS are sourced from the National Disability Insurance Agency’s publicly released reports. The NDIS quarterly reports and data downloads contain the latest available data on the funding and provision of NDIS supports. However, these do not include comprehensive breakdowns for all participant groups, such as First Nations people. Data on specific participant groups are periodically released in a series of special reports, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants: 30 June 2019.

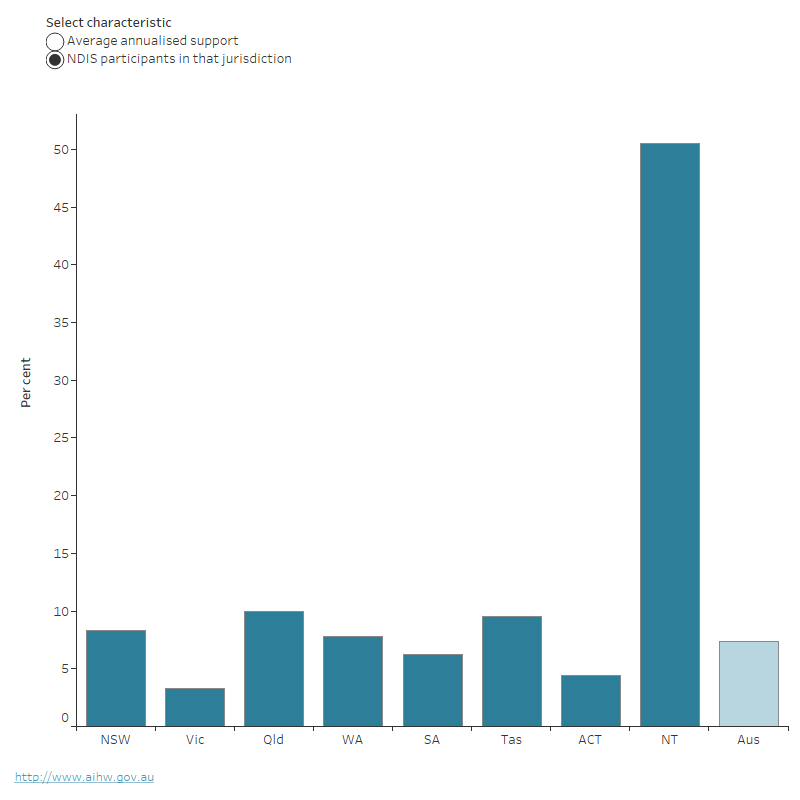

The proportion of First Nations NDIS participants has increased over time – from 6.2% (or around 19,200) in September 2019 to 7.4% (42,600) in December 2022 (NDIA 2023a).

The average annualised committed support provided to First Nations NDIS participants can provide an indication of the relative amount of support they receive. Not all committed support, however, may have been accessed or used by participants. The average annualised committed support is calculated using participants’ support budget converted to a yearly rate and divided by the number of participants (rounded to the nearest thousand dollars).

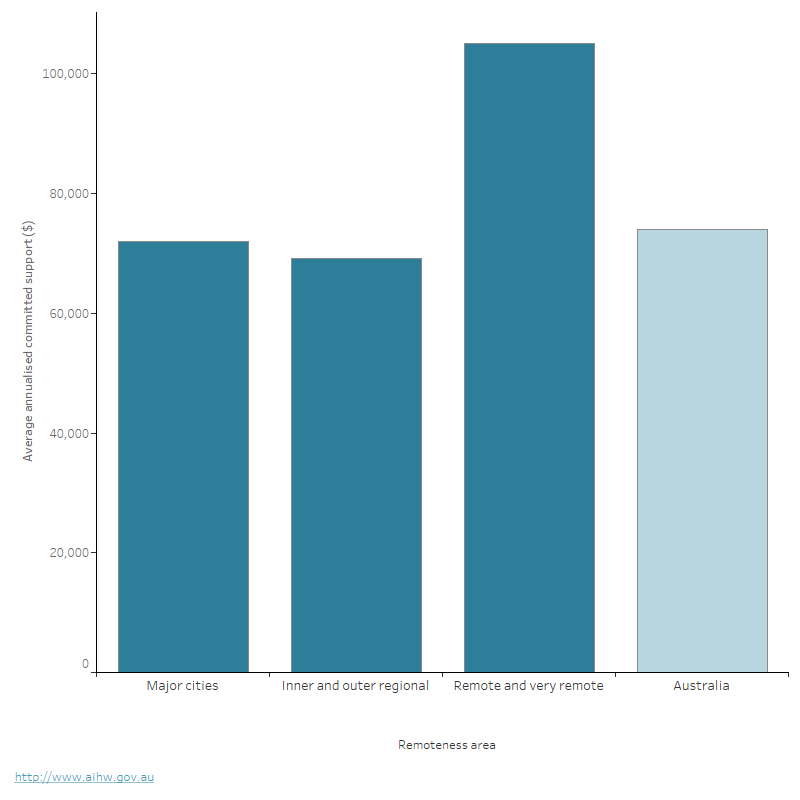

Among the First Nations NDIS participants on 31 December 2022:

- the average annualised committed support was $74,000

- there were 18,900 participants in Major cities and 19,400 participants in Inner and outer regional areas, averaging support amounts of $72,000 and $69,000 respectively

- there were 4,300 participants in Remote and very remote areas averaging $105,000

- the Northern Territory had the highest average support with $152,000, while Victoria had the lowest average support with $59,000 (NDIA 2023b; figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Average annualised committed support amounts for First Nations NDIS participants and proportion of First Nations NDIS participants, by jurisdiction, at 31 December 2022

This chart shows that the Average annualised committed support amounts First Nations people with disability received, and the proportion of First Nations NDIS participants, varies by jurisdiction:

- Average annualised committed support was $63,000 in New South Wales, $59,000 in Victoria, $71,000 in Queensland, $92,000 in Western Australia, $78,000 in South Australia, $67,000 in Tasmania, $61,000 in the Australian Capital Territory, $152,000 in the Northern Territory, and $74,000 nationally.

- The proportion of First Nations NDIS participants was 8.3% in New South Wales, 3.3% in Victoria, 10.0% in Queensland, 7.8% in Western Australia, 6.2% in South Australia, 9.5% in Tasmania, 4.4% in the Australian Capital Territory, 50.5% in the Northern Territory, and 7.4% nationally.

Note: The average annualised committed support amounts are rounded to the nearest thousand dollars.

Source: NDIA 2023b.

Figure 3: Average annualised committed support amounts for First Nations NDIS participants, by remoteness, at 31 December 2022

This chart shows the Average annualised committed support amounts First Nations people with disability received varied by remoteness area – $72,000 in Major cities, $69,200 in Inner and outer regional areas (combined): $105,000 in Remote and very remote areas (combined), and $74,000 nationally.

Note: The average annualised committed support amounts are rounded to the nearest thousand dollars.

Source: NDIA 2023b.

First Nations people with disability in remote communities, along with their families and carers, can face particular challenges such as:

- limited service choice and availability

- the need for travel and transportation

- availability of trained professionals

- issues relating to service/support quality

- lack of alternative accommodation options

- the achievement of positive outcomes for those most in need (NDIA 2016; PwC 2018).

The higher average annualised committed NDIS support for First Nations people in Remote and very remote areas compared with other remoteness areas could be one indication of these challenges. This also applies to the Northern Territory, as a significant proportion of the population in the Northern Territory live in rural, remote and very remote locations (NTMHC 2017).

Income support payments

Disability Support Pension (DSP) is the primary income support payment for people aged 16 and over with disability who have a reduced capacity to work because of their impairment. In December 2022, 58,500 First Nations people were receiving DSP, making up 7.6% of total recipients (DSS 2023).

Carer Payment provides income support for carers who are unable to support themselves through substantial paid employment because of the demands of providing constant care to a person with disability, a medical condition, or who is frail aged. In December 2022, 20,000 First Nations people were receiving Carer Payment, making up 6.6% of total recipients (DSS 2023).

Carer Allowance is a supplementary payment for carers who provide additional daily care and attention to someone with disability, a medical condition, or who is frail aged. In December 2022, 28,900 First Nations people were receiving Carer Allowance, making up 4.6% of total recipients (DSS 2023).

For more information on these payments, see Specialised supports for people with disability, Disability Support Pension, Carer Payment and Informal carers.

Homelessness services

People with disability who are homeless or at risk of homelessness can receive support from specialist homelessness services (SHS). In 2021–22, 25% (1,720) of SHS clients with severe or profound disability who provided information about their Indigenous status were First Nations people (AIHW 2022).

Informal care

A person’s interaction with both formal and informal welfare support and services can help support their wellbeing. Informal (unpaid) care provided by family, friends or neighbours within the context of an existing relationship often complements formal (paid) services from government and other organisations. The demands of the role, however, often go beyond what would normally be expected of the relationship.

The 2021 Census included a question about whether people had provided unpaid assistance to someone with disability, a long-term health condition or a problem related to old age in the 2 weeks before Census night. In 2021, of First Nations people aged 15 and over for whom responses to this question were provided:

- an estimated 15% (or 76,600 First Nations people) had provided unpaid assistance to someone with disability, a long-term health condition or a problem related to old age in the 2 weeks before Census night, staying constant from the rate in 2016 (15%)

- an estimated 18% (or 48,100) of females had provided unpaid assistance, compared with 12% (28,500) of males

- the proportion who had provided unpaid assistance was similar among First Nations people living in remote and non-remote areas (an estimated 16% or 11,600, and 15% or 46,700, respectively) (ABS 2022b).

For more information, see Informal carers.

The impact of COVID-19

First Nations people face increased risk of contracting and developing serious illness from COVID-19 compared with non-Indigenous Australians (Disability RC 2020).

Looking at the impact of COVID-19 on First Nations people with disability specifically, however, is challenging as data on this population are either not collected at all, not publicly available, or not regularly published. In particular, while some data are available by either disability status or by Indigenous status, data are rarely publicly available by both. For example:

- While the Department of Health and Aged Care collects data about COVID-19 infections, hospitalisations and deaths among First Nations people, data are not generally available by disability status.

- The primary source of disability support services data (that is, data collected as part of the NDIS) includes information on COVID-19 infections but these data are not regularly reported. Researchers, academics and government agencies/ departments, however, can submit a data request to the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) for a tailored NDIS data release.

- While the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission’s activity reports include data on complaints and compliance activities related to COVID-19, and on COVID-19 infections among NDIS participants, these are not available by Indigenous status.

- The main First Nations-specific primary health care data collections, the national Key Performance Indicators and the Online Services Report, do not collect data by disability status or on COVID-19 infections.

Some indirect inferences about the impact of COVID-19 on First Nations people with disability could be made by looking at changes in the First Nations disability population or at changes in the use of NDIS services by First Nations people. These data, however, would be difficult to interpret – for example, it is not always possible to separate the data into time periods that would allow clear comparison of before or during the pandemic; and some data, such as SDAC, are not regularly available.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on disability for First Nations people, see:

- ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability (ABS)

- People with disability in Australia

- Reporting on Australia's Disability Strategy.

For more information on First Nations participants of the NDIS, see the NDIA's:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2011) Microdata and TableBuilder: Census of Population and Housing: Census 2011, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 26 May 2023.

ABS (2016) Microdata and TableBuilder: Census of Population and Housing: Census 2016, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 26 May 2023.

ABS (2019a) Sources of data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with disability, 2012–2016, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 30 January 2023.

ABS (2019b) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 30 January 2023.

ABS (2019c) Microdata and TableBuilder: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Australia 2018–19, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 26 May 2023.

ABS (2021) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 26 May 2023.

ABS (2022a) Disability and carers: Census 2021, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 13 January 2023.

ABS (2022b) Microdata and TableBuilder: Census of Population and Housing: Census 2021, AIHW analysis of TableBuilder, accessed 26 May 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2022) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2021–22, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 13 January 2023.

AIHW and NIAA (National Indigenous Australians Agency) (2022) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: 1.14 Disability, AIHW and NIAA, Australian Government, accessed 3 April 2022.

Disability RC (Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability) (2020) Statement of concern: The response to the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disability, Disability RC, Australian Government, accessed 26 May 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2023) DSS benefit and payment recipient demographics – quarterly data, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 1 May 2023.

NDIA (National Disability Insurance Agency) (2016) Rural and remote strategy 2016–2019, NDIA, Australian Government, accessed 26 May 2023.

NDIA (2023a) NDIS (National Disability Insurance Scheme) Data downloads, NDIA, Australian Government, accessed 1 May 2023.

NDIA (2023b) NDIS Quarterly reports, NDIA, Australian Government, accessed 1 May 2023.

NTMHC (Northern Territory Mental Health Coalition) (2017) The provision of services under the NDIS for people with psychosocial disabilities related to a mental health condition, Parliament of Australia website, accessed 29 March 2021.

PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers) (2018) Engaging Aboriginal community controlled organisations (ACCOs) in disability service provision in the NT, Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet website, accessed 29 March 2021.