Employment and unemployment

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Employment and unemployment, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Employment and unemployment. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/employment-unemployment

MLA

Employment and unemployment. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/employment-unemployment

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Employment and unemployment [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/employment-unemployment

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Employment and unemployment, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/employment-unemployment

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Employment underpins the economic output of a nation and enables people to support themselves, their families and their communities. Employment is also connected to physical and mental health and is a key factor in overall wellbeing.

This page explores key measures for reporting on participation in the labour market including employment, unemployment and underemployment (see Labour force definitions). It explores these patterns from the early months of 2020 – with the introduction of social distancing and other business-related restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 – until July 2023 (the latest available data at the time of writing). It provides longer term trends to highlight the impact of the economic downturn during the pandemic on employment and how the recovery compares with that for previous recessions and economic downturns. See glossary for definitions of all terms used on this page.

Unless otherwise stated, data on this page are sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Labour Force Survey (LFS). It includes data from 1978, when this Labour Force series commenced, up to July 2023 unless otherwise stated.

Data from the ABS LFS are used to report on labour market participation measures – employment, unemployment, underemployment, and participation in the labour force. The information presented on this page uses the original and seasonally adjusted data series where available. Information is also presented on labour force experiences, such as casual employment and those marginally attached to the labour force.

This box presents summarised definitions of these measures. See ABS Standards for labour force statistics for further details (ABS 2018).

Employment rate (also known as the employment-to-population ratio) describes the number of employed people aged 15 and over as a proportion of the civilian population. Employed people includes those who have a job (for at least 1 hour during the reference period). This could be full-time, part-time, or away from work during the reference period. On this page, the employment rate refers to the ‘working age population’, those aged 15–64. This age restriction has been applied as it is important to account for the size of the population when monitoring longer term trends in employment rates, given the growth in the population aged 65 and over in recent decades.

Despite increases to the qualifying age for Age Pension in recent years (from 65.5 on 1 July 2017 to 67 on 1 July 2023), the ‘working age’ population on this page is defined as those aged 15–64 for consistency with previous reporting and for comparability across the reporting period (1978 to 2023).

Unemployment rate describes the proportion of the population aged 15 and over in the labour force who are unemployed. Unemployed is defined as those not employed in the survey reference week who had either:

- actively looked for work in the last 4 weeks and were available for work in the reference week or

- been waiting to start a new job within the last 4 weeks and could have started had it been available.

Underemployment rate describes the proportion of the population aged 15 and over in the labour force who are underemployed. Underemployed is defined as those who are either:

- employed part time who want to work more hours and are available to start working more hours within the next 4 weeks or

- employed full time but worked fewer than 35 hours during the survey reference week for economic reasons (including being stood down or insufficient work being available).

Labour force participation rate describes the proportion of the population aged 15 and over who are in the labour force (employed or unemployed). On this page, the labour force participation rate refers to the working age population, those aged 15–64.

Part-time employment in the LFS includes people who usually work less than 35 hours per week (in all jobs).

Full-time employment in the LFS includes people who usually work 35 hours or more per week (in all jobs).

Casual employment describes a large variety of work arrangements, and typically includes employees who do not tend to have leave entitlements (such as paid sick leave or annual leave). Such entitlements are usually for non-casual or permanent employees. Note that in March 2021, a statutory definition for casual work was introduced. This definition states an employee is casual if they accept an offer of employment without a firm advance commitment to ongoing work with an agreed pattern of work (Fair Work Ombudsman 2021). However, data presented on this page are based on currently available data from the ABS LFS on employees without leave entitlements that are used as a proxy for casual employment.

JobKeeper and JobSeeker Payments and ABS LFS definitions

In response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Australian Government introduced various economic support packages to protect the economy and offset the adverse impacts on the labour market from the measures introduced earlier to slow the spread of COVID-19 (such as widespread social distancing and other business-related restrictions). The JobKeeper Payment wage subsidy scheme was one of the largest of these support packages. It allowed many employees who otherwise may have lost their jobs to remain connected with their employer.

People who received the JobKeeper Payment were counted as being employed in the ABS LFS, as the LFS considers people to be employed if they were away from their job for any reason (including if they were stood down) and were paid for some part of the previous 4 weeks (including through the JobKeeper scheme) (ABS 2020a).

People who received the JobSeeker Payment were classified in the ABS LFS based on their labour market activity. Between March 2020 and March 2021, the mutual obligation requirements that people till then ordinarily had to meet to receive the JobSeeker Payment (which could include looking for work or studying) were suspended, in response to the business and activity restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These changes may have influenced whether people were actively searching for jobs – which would affect whether they were classified as ‘unemployed’ or ‘not in the labour force’ in the ABS LFS. They would, however, remain as ‘not employed’ in the ABS LFS unless they actually had a job.

See glossary for definitions of the terms used in this box

In July 2023, the seasonally adjusted:

- employment rate (for people aged 15–64) was 77.5%

- unemployment rate was 3.7%

- underemployment rate was 6.4%

- labour force participation rate (for people aged 15–64) was 80.6% (ABS 2023a).

Employment

Since 1978, when the Labour Force series began, the employment rate has been generally increasing, associated with rises in female labour force participation. However, over this time, there were several economic downturns (the early 1980s and 1990s recessions, the 2008–09 global financial crisis (GFC) and the COVID-19 pandemic) that resulted in falls in the employment rate.

Following these recessions and economic downturns, the seasonally adjusted employment rate (for those aged 15–64) took many years to recover, as highlighted below. In contrast, the employment rate had recovered within one year of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (see ‘Chapter 3 Employment and income support following the COVID-19 pandemic’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights for more detail).

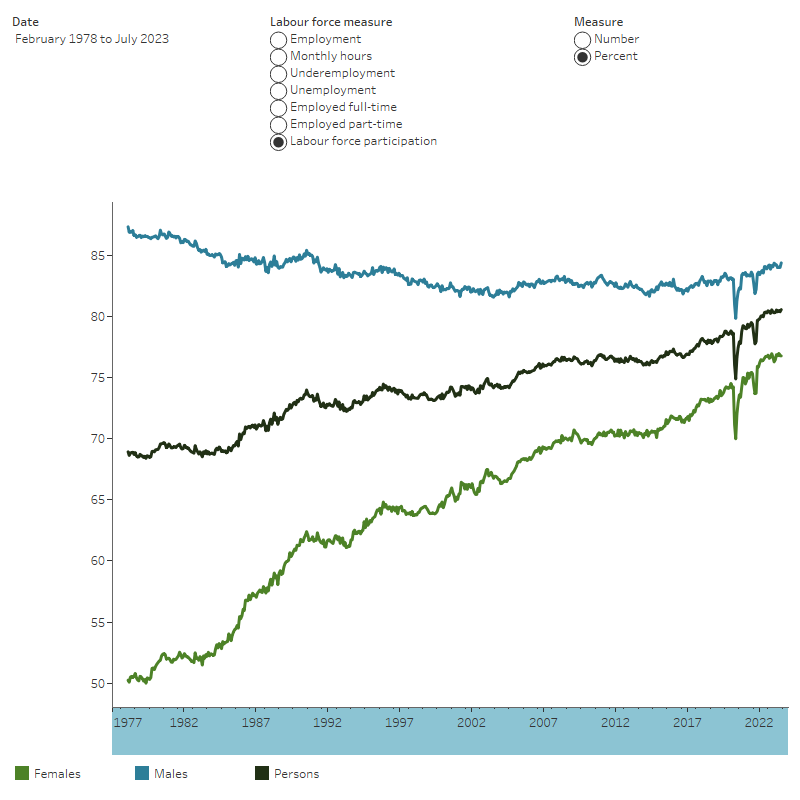

Between 1978 and July 2023, the seasonally adjusted employment rate for people aged 15–64 (Figure 1):

- decreased from 66% in 1981 to 62% in 1983, before increasing to 69% in 1990 and then falling again to 64% in 1993

- gradually increased to 73% in 2007 and remained relatively stable around 71–73% until 2017

- increased to 74% between 2018 and March 2020

- decreased to 69.5% in May 2020 (lowest level since 2003), in response to measures introduced to contain the spread of COVID-19

- gradually increased to 75.6% in July 2021, and then fell to 73.7% in October 2021 (301,400 fewer employed people than in July 2021), coinciding with the tightening of restrictions and lockdowns in response to containing the spread of the Delta variant of the coronavirus

- increased again reaching a record high of 77.7% in November 2022 and then returned to a similar level (77.6%) in March 2023 and remained relatively stable in most months to July 2023, despite some fluctuations between December 2022 and April 2023. In July 2023 there were 1.0 million more employed people than in March 2020.

Figure 1: Trends in labour force measures, by sex, 1978 to 2023

The line chart shows an increase in employment, from just under 6 million people in February 1978 to just over 14 million in May 2023, or an increase in the seasonally adjusted employment rate (15–64) from 64.3% to 77.6%. The employment rate for females increased over this period, while it declined slightly for males. From March to May 2020, the employment rate declined from 74.4% to 69.5%, before increasing to a record high of 77.7% in November 2022 (with a dip in October 2021). Both underemployment and unemployment have fluctuated since 1978 in line with recessions and economic downturns. The underemployment rate reached 13.7% in April and unemployment reached 7.5% in July 2020. Monthly hours worked and labour force participation steadily increased from 1978 until March 2020, when they declined sharply. Between 1978 to 2023, more males than females have been employed full-time, while more females have been employed part-time.

Notes

- The employment rate and labour force participation rate are proportions of the working age population aged 15–64, and the underemployment and unemployment rate are proportions of the population aged 15 and over in the labour force.

- Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Labour Force Australia (ABS 2023a: Table 1, Table 18, Table 19, Table 22).

Monthly hours worked

Another way to understand changes in employment is to examine monthly hours worked, which may highlight the impact of a recession or economic downturn on the labour market before it is reflected in changes to the employment rate. Reducing hours during an economic downturn is often an early response taken by businesses to minimise people losing their jobs (ABS 2020b).

Consistent with the above-mentioned growth in employment, the total number of monthly hours worked has been generally increasing since 1978. However, over this period, there have been some monthly dips in hours worked, consistent with previous recessions in the early 1980s (monthly falls up to 2.5%), 1990s (monthly falls up to 1.6%), and the economic downturn in 2008–09 (monthly falls up to 2.0%). The decline in monthly hours worked at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was by far the steepest on record, with a drop of 10% between March and April 2020. The high number of people receiving the JobKeeper Payment in April 2020 (3.4 million), who were counted as employed even if they were working zero hours, may have contributed to this large decline in monthly hours worked (AIHW 2021a).

Hours worked in July 2023 was 11% higher than in March 2020 and 5.2% and 9.7% higher than July 2022 and July 2021, respectively, continuing the upward trend that was observed prior to the pandemic (Figure 1).

For more information on hours worked see ‘Chapter 3 Employment and income support following the COVID-19 pandemic’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights.

Part-time employment

The hours an individual works is an important aspect of their employment. For many people, working part time enables them to balance work with other activities, such as a caring responsibility, study, or transition to retirement.

The seasonally adjusted share of employed people in part-time employment reduced from 32% in March 2020 to 30% in April–May 2020, similar to the levels observed prior to 2013 (ABS 2023b; Figure 1). It returned to 31–32% for most months from June 2020 until April 2022, then stabilised around 30% until July 2023.

For more information on part-time employment see ‘Chapter 3 Employment and income support following the COVID-19 pandemic’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights.

Casual employment

The share of all employees engaged on a casual basis (defined on this page as those without leave entitlements) in Australia grew from the late 1980s to the early 2000s (25% in August 2003) but remained relatively steady in the 6 years to February 2020 (around 24–25%) (ABS 2022b). Since then, there have been various fluctuations in the proportion of employees engaged on a casual basis coinciding with measures introduced in March 2020 to contain the spread of COVID-19.

Between 2020 and 2023, the proportion of employees engaged on a casual basis:

- decreased from 24.1% in February 2020 to 20.6% in May 2020, the lowest rate since August 1991

- progressively increased to 23.6% by May 2021

- decreased again in August 2021 to 22.6% and remained around 23% until February 2023 when it declined again to 22.1% and has remained relatively stable until May 2023 (ABS 2023b: Table 13).

Casual workers may work full time or part time. Both the decline in casual employment at the onset of the pandemic, and the recovery since, have been driven by part-time casual employees, who made up 66% of the fall in casual employment from February–May 2020 and 70% of the growth from May 2020 to May 2023. Conversely, the decline in non-casual employment from February to May 2020 was driven by full-time employment (87%).

Retail and accommodation, and food services industries – among the most affected by social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic – account for a large proportion of casual workers across Australia (Parliamentary Library 2020).

Note that data reported on this page uses a person’s lack of leave entitlements (such as paid sick leave and annual leave) as a proxy for casual employment, rather than the statutory definition of casual employment, based on currently available data from the ABS LFS (see Labour force definitions box for further details).

Underemployment

Alongside the employment rate – whereby a person is counted as employed regardless of how many hours they have worked in the reference period – the underemployment rate provides important insights on whether people are working enough hours to meet their needs. People are underemployed if they are part time and want more hours, or full time and worked part-time hours in the reference week for economic reasons (see Labour force definitions box above for more detail).

While the seasonally adjusted underemployment rate for the population aged 15 and over has been gradually increasing since the late 1970s, it has also fluctuated in line with the above-mentioned recessions and economic downturns between 1990 and 2023 (Figure 1). In particular, the underemployment rate rose steeply in the early months of the pandemic, when many employees had their hours reduced.

The seasonally adjusted underemployment rate for the population aged 15 and over:

- increased from around 4% in early 1990 to around 7% in 1992 and then remained relatively stable until 2009

- increased to around 8% in 2009, declined again to around 7% between 2010 and 2014 and then remained around 8–9% between 2014 and March 2020

- rose steeply, from 8.7% in March 2020 to 13.7% in April 2020 – the highest on record since the current Labour Force series began in 1978 – before gradually declining to 6.2% in April 2022 (despite some fluctuations from July to October 2021). In the 12 months to April 2023, the underemployment rate fluctuated between 5.8%–6.2% before increasing slightly to 6.4% in May 2023 and remaining steady until July 2023.

Long-term trends in seasonally adjusted underemployment rates up until the pandemic were driven by the underemployment of part-time workers, reflecting the growing share of part-time employment in the labour market and underemployment among part-time workers. At the onset of the pandemic, however, almost all of the increase in underemployment was people who were employed full time and working fewer hours for economic reasons. This is likely to have been influenced by the JobKeeper payment as some people on JobKeeper worked zero or reduced hours; see Labour force definitions above for further details).

The seasonally adjusted underemployment rate has been consistently higher for females than males since the current Labour Force series began in 1978. In July 2023, the underemployment rate was 7.5% for females and 5.3% for males.

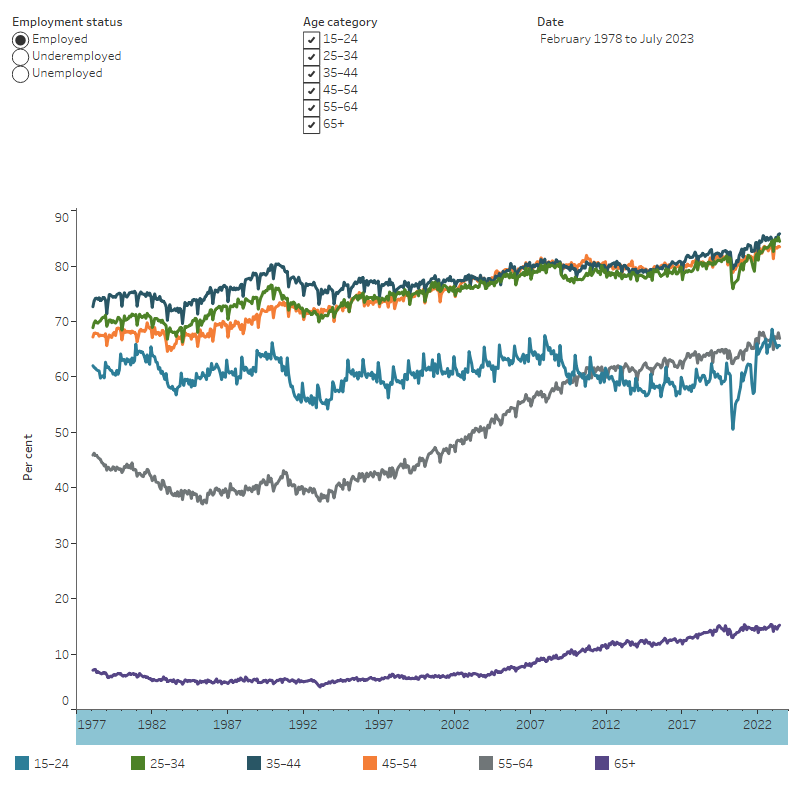

Employment by age groups

The employment rate has increased for all age groups of ‘working age’ (15–64) people since the current Labour Force series began in 1978 (see Labour force definitions). By early 2021, the employment rate had recovered to pre-pandemic levels (March 2020) for all age groups. By June 2023, it was around 2–5 percentage points higher for the 25–64 age groups than prior to the pandemic (Figure 2).

In June 2023, the 25–34, 35–44 and 45–54 age groups had employment rates of 83–86%. In contrast, employment rates were lower for those aged 15–24 and 55–64 (66% and 67%, respectively), reflecting that people in these age groups are transitioning into and out of work.

Over the last 40 years, the increase in employment rates for people aged 15–24 has been considerably slower than for other age groups – increasing by 4 percentage points between 1978 and 2023 (from 62% to 66%) compared with increases of 13–21 percentage points for other age groups. The slower growth for the 15–24 age group may reflect delayed entry into the labour market due to more people under 24 remaining in education/training over the last few decades. According to the ABS Survey of Education and Work, people aged 15–24 in 2022 were 3 times as likely to be engaged in tertiary education than 40 years ago. In 2022, 9.3% of males and 13.6% of females aged 15–24 have a Bachelor degree or above, which require longer periods of study at university than other non-school qualifications. This compares with 2.6% and 3.7%, respectively, in 1982 (ABS 2022a).

The 55–64 age group have:

- a lower employment rate – 67%, compared with 83–86% for those aged 25–54 in 2023

- the fastest growth in employment rates – 21 percentage point increase between 1978 and 2023, from 46% to 67%.

This reflects the increasing retirement age and more mature aged Australians remaining in the workforce for longer (AIHW 2021b).

People aged 15–24 are also more heavily affected by economic downturns as they are more likely to be engaged on a casual or part-time basis than other age groups – 53% of employed people in this age group work part-time compared to 22–30% of other age groups. People aged 15–24 had the steepest falls in employment rates at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a fall of 10 percentage points reaching the lowest rate on record. However, they were also the first age group to return to pre-pandemic levels and had the largest percentage point increase in employment rates between March 2020 and June 2023 (Figure 2). See ‘Chapter 3 Employment and income support following the COVID-19 pandemic’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights for more information.

Figure 2: Employment, underemployment and unemployment rates, by age, 1978 to 2023

The line chart shows employment, underemployment and unemployment rates by age groups. The 15–24 age group showed slow growth in employment rates (from 62% in February 1978 to 66% in May 2023), whereas the 55–64 age group showed rapid growth (from 46% in February 1978 to 68% in May 2023). The 15–24 age group consistently had the highest unemployment rate (14% in February 1978 and 7.4% in May 2023) and underemployment rate (3.1% in February 1978 and 14% in May 2023) compared with other age groups.

Notes

- Employment rate is a proportion of the working age population aged 15–64, while the unemployment and underemployment rates are proportions of the population aged 15 and over in the labour force.

- Employment rates and unemployment rates for people 55 and over are based on the original LFS, otherwise data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Labour Force Australia (ABS 2023a: Table 22, 2023b: Table 1).

Employment by sex

Over the last 40 years, the employment rate for females aged 15–64 has been generally rising, while the male employment rate has been slowly falling:

- Between February 1978 and January 2020, the female employment rate increased from 46% to 71%, the highest rate at that point since the current labour force data series began in 1978.

- The male employment rate fell from 82% in 1978 to 80% before the GFC (most of 2007–2008) and to 79% in January 2020.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, there were differences in employment levels between males and females:

- Between March and May 2020, the number of employed females (seasonally adjusted) fell by 7.9% compared with a 5.7% fall for males.

- The number of employed females increased at a faster rate than for males between June 2020 and May 2021 (a 7.3% and 5.0% increase, respectively).

- Females returned to pre-pandemic employment rates earlier than males (February 2021 compared with May 2021 for males).

- In November 2022, both males and females reached highest employment rates in over 2 decades, 81.2% and 74.2%, respectively – for females the highest on record (since 1966), and for males the highest since the early 1980s.

- The employment rate for males then declined slightly to 80.6% in April 2023 before increasing to 81.1% in July 2023, while the female employment rate declined to 73.6% in January 2023 before increasing again to 73.9% in July 2023 (Figure 1).

For more information on the impact of COVID-19 on employment in 2020–21, see ‘Chapter 4 The impacts of COVID-19 on employment and income support in Australia’ in Australia’s welfare 2021: data insights.

Employment by education level

People with higher levels of educational attainment are generally more likely to have better employment outcomes, including increased real wages (National Skills Commission 2021).

The number of employed Australians with a Bachelor degree or above as their highest educational qualification increased by 47% from August 2015 (earliest data from ABS LFS) to May 2023 – from an estimated 3.6 million to 5.2 million, or from 30% to 37% of all employed people aged 15 and over. Corresponding with this increase, there was a slight decline in the proportion of employed Australians whose highest educational qualification was Certificate III/IV (from 21% to 18%) or Year 12 or below (from 35% to 32%) over this period.

At the onset of the pandemic, people with lower levels of education (Year 12 or below as their highest educational attainment) had much steeper declines in employment – average quarterly decline of 10% from February 2020 to May 2020, compared with an average decline of 1% for those with a Bachelor degree or above. This compares to minimal changes in employment (by 1–2%) for both those with a Bachelor degree or above, and those with Year 12 and below as their highest level of attainment, in the corresponding quarters in 2018 and 2019.

In May 2023, the employment rate of people with a postgraduate degree as their highest level of educational attainment was 83%, for people with a Bachelor degree it was 79%, and for people with Year 12 or equivalent it was 68% (ABS 2023b).

For more information see Primary and secondary schooling and Higher education, vocational education and training.

Unemployment

Since the early 1990’s, the unemployment rate has declined, reaching its lowest rate in 50 years in October 2022. Over this period, there have been various increases to the unemployment rate, coinciding with economic downturns due to the GFC and COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Over the last 40 years, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for people aged 15 and over:

- reached a peak of around 10–11% in the early 1990s, coinciding with the recessions in the early 1990’s

- decreased to around 4% for most of 2007 and 2008

- increased to 6% for most of 2009, following the GFC, and has generally remained around 5–6% between March 2010 and March 2020

- increased from 5.2% to 7.5% between March and July 2020, in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic

- gradually declined to 3.4% by October 2022 – the lowest rate in almost 50 years – before increasing slightly to 3.7% by July 2023 (172,400 fewer unemployed people than in March 2020).

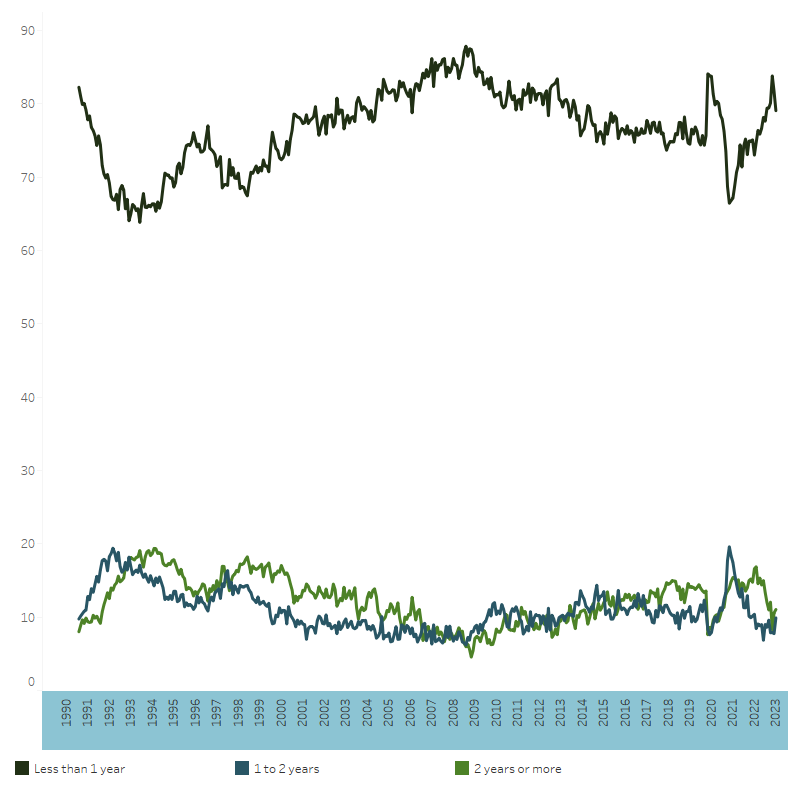

A period of unemployment can be a short-term transition between jobs, a long struggle to find work, or something in between. Long-term unemployment can detrimentally affect a person’s financial resources and their job prospects (Cassidy et al. 2020).

Of the 488,100 unemployed people aged 15 and over in June 2023:

- 79% (or 385,900) had been unemployed for less than 1 year

- 9.9% (or 48,400) had been unemployed for 1–2 years

- 11% (or 53,900) had been unemployed for 2 or more years (ABS 2023b: Table 14a).

Duration of unemployment has fluctuated over the past 2 decades, including increases in the number of people who are short-term unemployed (a year or less) at the onset of each recession and economic downturn (including in the early 1980s and 1990s, the 2008–09 GFC and COVID-19). This is then followed by increases in those unemployed for 1–2 years and 2 or more years in subsequent years (Figure 3). In particular:

- Between March and April 2020 (at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic), the proportion of short-term unemployed (less than 1 year) had the largest monthly increase since the data series began in 1991 (from 76% to 84%). Note this was still lower than the peak in January 2009 (88%).

- In April 2021 (12 months later), the proportion of those unemployed for 1–2 years (20%) was the highest it has been in 30 years (since 1991). It was almost twice as high as in previous years (11–13% for the corresponding months in 2017–2019).

- In July 2022, the proportion of long-term unemployed (2 or more years) increased slightly to 17% (compared with 12–15% for the corresponding months in 2017–2019). It was similar to the level in 2000, but still below the high levels observed following the early 1990’s recession (18–19% for most of 1993–1994).

Figure 3: Proportion of unemployed people by duration of unemployment, from January 1991 to June 2023

The line chart shows the proportion of unemployed people who have been unemployed for less than a year, for 1–2 years, or for 2 years or more. Duration of unemployment has fluctuated since 1991, including increases in the number of people who are unemployed for a year or less at the onset of each recession or economic downturn followed by increases in those unemployed for 1–2 years and 2 or more years in subsequent years. Between March 2020 and April 2020, the proportion of people unemployed for less than 1 year had the largest monthly increase since the data series began in 1991 (from 76% to 84% of all unemployed people). In April 2021 (12 months later), the proportion of those unemployed for 1–2 years was the highest it has been since 1991 (20%). In July 2022, the proportion of people unemployed for 2 or more years increased to 17%, similar to the level in 2000, and larger than the proportions in the corresponding months in 2017–2019 (12–15%).

Note: Figure presents proportion of unemployed people by duration of unemployment, from January 1991 to June 2023.

Source: Labour Force Australia, detailed (ABS 2023b: Table 14a).

Not engaged in education, employment or training

Not participating in work or study can contribute to future unemployment, lower incomes and employment insecurity (Pech et al. 2009).

In May 2022 (the most recent data available), 1 in 4 (24%) people aged 15–74 were not engaged in education, employment or training (NEET). All age groups have seen declines in the proportion of those NEET between 2013 and 2022, from:

- 11% to 7.6% for those aged 15–24

- 18% to 13% for those 25–44

- 27% to 23% for those aged 45–64.

Between 2019 and 2020, there was a large increase in the proportion of people who were NEET across most age groups (24% to 28% for those aged 15–74). This was in line with declines in the above-mentioned employment measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (ABS 2022a). By May 2022, the proportion of each age group (between ages 15 and 74) that was NEET was between 2.5 and 4.8 percentage points lower than in May 2019.

Labour force participation

The seasonally adjusted labour force participation rate has been gradually increasing since the current LFS began in 1978 (69%), despite some fluctuations in line with recessions in the early 1980s and early 1990s.

Consistent with previous economic downturns, there was also a large fall in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic from 78.6% in March 2020 to a low of 74.9% in May 2020. It then gradually increased to a peak of 80.6% in November 2022 (highest on record), and then remained relatively stable to July 2023 (between 80.3–80.6%).

The share of females in the labour force has been steadily increasing over the past 50 years – from 36% in 1978 to 47% by July 2023. This is due to the number of females in the labour force almost tripling over this period compared with an 86% increase for males. When taking into account the size of the population over this 40-year period, the labour force participation rate for females increased by 27 percentage points (from 50% to 77%) compared with a 3-percentage point decline for males (from 87% to 84%; Figure 1).

Potential workers

In February 2023, of the 7.4 million people not employed, 1.8 million (25%) wanted to work (referred to as potential workers; ABS 2023c).

Of the 1.8 million people who wanted to work (potential workers):

- 467,800 (26%) looked for work

- 356,400 (20%) had a job to go to or return to

- 980,500 did not look for work.

Not potential workers

In February 2023, of the 7.4 million people not employed, 5.6 million people (76%) did not want to work or were permanently unable to work (not potential workers). Of these 5.5 million not potential workers, the majority (88% or 4.9 million) did not want to work while 691,100 (12%) were permanently unable to work. The main activities reported by those who did not want to work were:

- retirement (61% or 3.0 million)

- duties around the home (10% or 518,100)

- attending an educational institution (10% or 474,000)

- ill health or disability (6% or 301,200).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on employment and unemployment, see:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2018) Standards for labour force statistics, ABS website, accessed 3 May 2023.

ABS (2020a) Classifying people in the Labour Force Survey during the COVID-19 period, ABS website, accessed 3 March 2023.

ABS (2020b) Insights into hours worked, ABS website, accessed 11 May 2023.

ABS (2022a) Education and Work, Australia, May 2022, ABS website, accessed 28 March 2023.

ABS (2022b) Working arrangements, August 2022, ABS website, accessed 5 July 2023.

ABS (2023a) Labour Force, Australia, July 2023, ABS website, accessed 21 August 2023.

ABS (2023b) Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, June 2023, ABS website, accessed 3 July 2023.

ABS (2023c) Potential workers, February 2023, ABS website, accessed 5 July 2023.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2021a) Australia’s welfare 2021: data insights Chapter 4 ‘The impacts of COVID-19 on employment and income support in Australia’, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 March 2023.

AIHW (2021b) Older Australians, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 29 March 2023.

Cassidy N, Chan I, Gao A and Penrose G (2020) Long-term Unemployment in Australia, Reserve Bank of Australia, accessed 3 May 2023.

Fair Work Ombudsman (2021) Casual employees, Fair Work Ombudsman, Australian Government, Australian Government, accessed 3 May 2023.

National Skills Commission (2021) Australian Jobs 2021, National Skills Commission, Australian Government, accessed 24 March 2023.

Parliamentary Library (2020) COVID-19: Impacts on casual workers in Australia – a statistical snapshot, Parliamentary Library, Australian Government, accessed 3 May 2023.

Pech J, McNevin A and Nelms L (2009) Young people with poor labour force attachment: a survey of concepts, data and previous research, Australian Fair Pay Commission, accessed 3 May 2023.