Income and income support

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Income and income support, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Income and income support. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/income-support

MLA

Income and income support. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/income-support

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Income and income support [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/income-support

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Income and income support, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/income-support

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

A person’s wellbeing is influenced by many factors, but having an adequate income remains an essential component in measuring individual and household wellbeing. Adequate income can help people support themselves, their families, and their broader communities. For most people, income can be an indicator of a person’s ability to access food, clothing, education, housing and leisure activities. A person’s income is influenced by their economic circumstances, in particular employment status and type, hours worked, occupation, and government support through Australia’s social security system.

This page examines various measures that provide an overview of the economic wellbeing of Australians, including household income and income support payments through the social security system (see Income and Income support data sources). See glossary for definitions of terms used on this page.

Income and income support data sources

Income data

Several ABS data sources are used to report on income on this page:

Survey of Income and Housing 2019–20 – the latest available data from this survey has been used on this page to report on main sources of household income.

Consumer Price Index (September 1997 – June 2023) – the Consumer Price Index is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by households for a fixed 'basket' of goods and services. It measures household inflation and changes in price for categories of household expenditure.

Survey of Average Weekly Earnings (May 2012 – May 2023) – this survey is conducted twice a year in May and November and is the source of data on average weekly earnings. The data presented on this page are estimates of average weekly earnings (not including earnings from overtime) and are affected by compositional changes in employment. On this page, these data have been adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index.

National accounts: Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth (2003–04 to 2021–22) – integrates ABS micro and macro data to generate information on household income, consumption and wealth. This data source is used to report on equivalised disposable household income by income quintiles. The ABS Households Final consumption expenditure implicit price deflator was used to measure changes in household income by adjusting these data for changes in both prices and the composition of expenditure (ABS 2023b).

Wage price index (September 1997 – June 2023) – measures changes in the price of labour. This measure is compiled using hourly rates of pay for a sample of employee jobs and is therefore not affected by compositional shifts in employment. The WPI is also unaffected by the quality and quantity of work performed and does not reflect changes in payments for overtime work, or bonuses.

This page has also used the ANU COVID-19 Monitoring Survey Program (February 2020 to August 2023) and unpublished analysis from the ANU on projected household income to 2023.

Income support data

Income support data are sourced from the Department of Social Services payment demographic data (from September 2013 to March 2023) and previously unpublished data derived from Services Australia administrative data (June 2001 to June 2013).

What are the main sources of household income?

In 2019–20, about 3 in 5 (62%) households reported wages and salaries as their primary source of income, followed by government pensions and allowances (22%), superannuation (6.0%), and investment income (4.4%).

Government pensions and allowances were more likely to be the primary source of income for households in the lowest (63%) or second lowest (30%) income quintile compared with other quintiles (8.7% in the third to fifth quintiles; ABS 2022).

Have income levels changed over time?

Income from wages

Income from wages can be measured using several data sources. Average weekly ordinary time earnings (AWOTE) for full-time employees (see box above), from the ABS Survey of Average Weekly Earnings is one way to measure changes in weekly earnings (ABS 2023c). Movements in average weekly earnings can be affected by changes in both wage rates and in the composition of employment.

Prior to the onset of COVID-19 AWOTE grew at an average annual rate of 2.5% from November 2012 to November 2019 in nominal terms. In the 6 months to May 2020, AWOTE for full-time employees increased steeply by 3.3% (to $1,714). The sharp rise reflects compositional changes in the structure of employment in the early months of the pandemic, in particular the loss of relatively low paid jobs led to a rise in average earnings (ABS 2020b). From May 2020 to May 2023, AWOTE for full-time employees grew at an average annual rate of 2.4%.

From December 2001 to December 2019 the Consumer Price Index (CPI) (see box above) grew at an average annual rate of 2.4%. Consistent with the experience in other OECD countries, annual inflation has accelerated following the initial COVID-19 period. The CPI grew by 6.1% over the year to the June quarter 2022, which at the time was the fastest increase since June 2001. Annual growth in the CPI reached a peak of 7.8% over the year to the December quarter 2022. It has subsequently moderated to 6.0% over the year to the June quarter 2023.

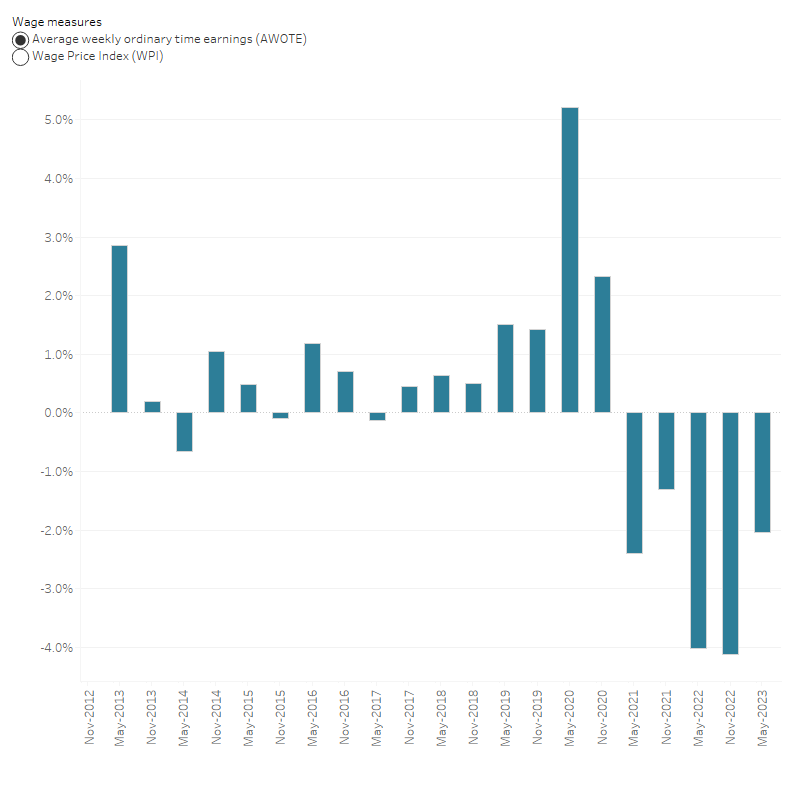

This rise in inflation has led to declines in the real value of wages. As Figure 1 shows after adjusting for changes in the CPI, real AWOTE has been falling in annual terms since May 2021. Real AWOTE fell by 4.1% over the year to November 2022, and by 2.0% over the year to May 2023. This compares to annual increases of 0.4–1.4% from November 2017 and November 2019.

Figure 1: Annual change in income from wages in real terms, June 2011 to June 2023

The chart shows annual changes in real AWOTE (May 2013 to November 2022) and real WPI (June 2011 to March 2023). Real AWOTE has been falling in annual terms since May 2021. Real AWOTE for full-time employees fell by 4.1% over the year to November 2022. This compares with annual increases of 0.4–1.4% to the November quarter in 2016 to 2019. The real WPI has been falling in annual terms since the June quarter 2021. Over the year to the March quarter 2023 the real value of the WPI fell by 3.1%.

Notes

- AWOTE and WPI data are seasonally adjusted.

- Data have been adjusted for changes in prices using the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Source: For AWOTE ABS 2023c Table 2, ABS 2023d Tables 1 and 2; for WPI ABS 2023e Table 1, ABS 2023d Tables 1 and 2.

The Wage Price Index (WPI) (see box above) measures changes in the price of labour. This measure is compiled using hourly rates of pay for a sample of employee jobs and is therefore not affected by compositional shifts in employment. The WPI, unlike measures of average weekly earnings, provides a measure of changes in wage rates. In other words, it shows how pay changes for a particular job.

Prior to the onset of COVID-19, annual growth in the WPI was quite subdued; it grew by an average annual rate of 2.2% between March quarter 2013 and March quarter 2020. However, during the early months of COVID-19 annual wage growth fell, with the WPI growing by 1.4% over the year to the September quarter 2020, the December quarter 2020 and the March quarter 2021. At 1.4%, annual WPI growth was at its lowest level since the introduction of this index in the late 1990s.

Annual growth in the WPI has subsequently accelerated with the WPI growing by 3.7% over the year to the March quarter 2023 (the fastest annual increase since September 2012) and by 3.6% over the year to the June 2023 quarter. This compares with average annual growth of 2.2% between June 2013 and June 2020.

The recent acceleration in growth in the WPI has not kept pace with inflation and as a result the real value of the WPI has been falling in annual terms since the June quarter 2021, as shown in Figure 1. Over the year to the June quarter 2023 the real value of the WPI fell by 2.3%.

Household income

While wages data provide important information on changes in living standards many families do not rely on income from wages, such as people who are retired or receiving income from other sources (for example government payments). For that reason, it is also important to look at changes in household income and how this has changed at different points of the income distribution.

The ABS has published estimates of household income, wealth and consumption using data from the Australian National Accounts (see box above) and other data.

In 2021–22, average equivalised gross disposable household income (equivalised income adjusts for household, size, and composition) was $139,064 per household (ABS 2023a).

Tables 1 and 2 show changes in nominal and real gross disposable income per household. The ABS Households Final consumption expenditure implicit price deflator was used to adjust these data for changes in prices.

Prior to the onset of COVID-19, real household income was growing across the income distribution with the fastest increases experienced by households in the highest and lowest quintile of the distribution both in nominal and in real terms. For example, for households in the highest and lowest quintiles average real equivalised gross disposable income per household grew at an average annual rate of 2.3% and 2.2%, respectively, between 2003–04 and 2019–20, compared with annual increases of around 1.5–1.8% in the other quintiles.

Following the onset of COVID-19 a different pattern was evident. From 2019–20 to 2020–21, the fastest increases in real equivalised gross disposable income per household were experienced by households in the lowest and second lowest quintiles of the income distribution (5.8% and 4.7% increases, respectively, compared to 3.0–3.7% increases for other quintiles). This reflects the COVID-related government economic support packages, such as the introduction of the Coronavirus Supplement for working-age income support recipients.

From 2020–21 to 2021–22, however, households in the lowest and second lowest income quintiles saw their real income fall (by 2.2% and 0.6%, respectively), in line with the unwinding of some economic support measures. This compares to slight increases of 0.9–1.2% in other quintiles. Real incomes for these households were still 3.5% higher (for the lowest quintile) and 4.1% higher (for the second lowest quintile) in 2021–22 than in 2019–20.

Over the whole period from 2003–04 to 2021–22, real incomes grew across the income distribution with the fastest growth experienced by households in the highest and lowest income quintiles (2.3% and 2.2% growth, respectively).

At $288,311 in 2021-22, average equivalised gross disposable income per household for the top quintile was 5.3 times as high as that for the lowest income quintile ($54,134). Net worth (wealth) per household at $3.2 million for the highest quintile was 5.9 times as high as that for the lowest quintile ($551,460).

The Gini Coefficient is a measure of income inequality that is often used in international comparisons. The coefficient varies between 0 and 1 with lower numbers representing less inequality and higher numbers representing more inequality. The latest ABS data (ABS 2022) shows that the GINI coefficient for equivalised disposable household income remained quite stable from 2007–08 (0.336) to 2019–20 (0.324) (ABS 2019).

Average annual change | 1st (most disadvantaged) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th (least disadvantaged) | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2003–04 to 2019–20 | 4.3% | 3.9% | 3.7% | 3.6% | 4.5% | 4.1% |

2019–20 to 2020–21 | 6.9% | 5.8% | 4.7% | 4.8% | 4.0% | 4.7% |

2020–21 to 2021–22 | 0.8% | 2.4% | 3.9% | 4.1% | 4.3% | 3.7% |

2003–04 to 2021–2022 | 4.3% | 4.0% | 3.8% | 3.7% | 4.4% | 4.1% |

Note: Equivalised gross disposable household income by income quintile has been adjusted for changes in prices using the ABS Households Final consumption expenditure implicit price deflator.

Sources: ABS 2023a, 2023b.

Average annual change | 1st (most disadvantaged) | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th (least disadvantaged) | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2003–04 to 2019–20 | 2.2% | 1.8% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 2.3% | 2.0% |

2019–20 to 2020–21 | 5.8% | 4.7% | 3.6% | 3.7% | 3.0% | 3.7% |

2020–21 to 2021–22 | -2.2% | -0.6% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 0.6% |

2003–04 to 2021–2022 | 2.2% | 1.9% | 1.7% | 1.6% | 2.3% | 2.0% |

Note: Equivalised gross disposable household income by income quintile has been adjusted for changes in prices using the ABS Households Final consumption expenditure implicit price deflator.

Sources: ABS 2023a, 2023b.

To compliment the ABS data, the AIHW commissioned the ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods to generate estimates of changes in equivalised disposable income at different points of the income distribution. These estimates were generated by the centre using the ANU’s microsimulation model, PolicyMod. PolicyMod effectively creates a new ABS Survey of Income and Housing (SIH) for each year beyond the base year (in this case 2017–18 SIH). The results are only a simulation of income change. The simulation updates incomes using the best publicly available data, such as wages and employment, and also updates to social security and personal income taxation policy. The simulated data cannot be expected to accurately cover all changes in the economy and do not directly model behavioural change that may flow from policy change.

The ANU PolicyMod estimates were projected to December 2022. For the period 2019 to the end of 2022, the PolicyMod estimates suggest that the fastest growth in nominal incomes occurred for households in the highest income quintile (quintile 5) with overall growth of 14.4% (average annual growth rate of 4.6%) and the lowest income quintile (quintile 1; total growth 12.7% and average annual growth rate of 4.1%) (see Table 3).

In 2022, income growth differed across the income distribution. The lowest income quintile was estimated to have an income growth of 4.6% compared to 3.8% for the highest income households. The stronger growth of income for the lowest quintile is driven by the indexation of income support payments by the CPI which in 2022 grew more strongly than wages. Income support payments go mostly to low-income households.

The standard approach for adjusting changes in income for changes in prices is to create real estimates that use overall price indexes such as the CPI. While this approach is sound, it does not take into account that different households may face different financial pressures. The ANU has constructed a living cost index that accounts for different prices faced at different points of the income distribution. As an example, rises in living costs were more substantial for higher income households in 2022 mostly due to mortgage cost increases impacting higher income households more so than lower income households who are more likely to rent. Rents while increasing sharply through the latter part of 2022 and through 2023, have not increased nearly as sharply as mortgage costs.

Using the ANU’s living cost index, living costs grew at a faster rate than incomes in 2022 and as a result real incomes fell across the income distribution with the largest falls affecting the middle-income quintiles (3 and 4) (see Table 4). Over the whole period from 2019 to 2022 real incomes rose for the bottom quintile (0.6%), the second (0.1%) and the top quintile (2.0%), while the third and fourth quintiles experiencing modest declines of 1.6% and 1.8%, respectively.

These estimates do not take account of changes announced in the 2023–24 Federal Budget nor increases to the minimum and award wages that took effect on 1 July 2023. In addition, inflation is forecast to fall. According to the 2023–24 Federal Budget the CPI is forecast to grow by 3 1/4% over the year to the June quarter 2024 after growing by 6% over the year to the June quarter 2023.

Income quintile | 2019–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2019–2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

Quintile 1 | 7.7% | 4.6% | 12.7% |

Quintile 2 | 9.3% | 2.6% | 12.1% |

Quintile 3 | 8.9% | 1.4% | 10.4% |

Quintile 4 | 8.5% | 1.5% | 10.1% |

Quintile 5 | 10.2% | 3.8% | 14.4% |

All households | 9.2% | 2.8% | 12.2% |

Notes

- PolicyMod is based on the ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2017-18 and all dollar variables uprated with latest available data such as average weekly earnings, rental incomes and national accounts data.

- Projections for wages and income support payments set to government budget estimates and projections. Policy changes include those up to 2023 Budget and assumes all measures pass legislation.

- Income quintile calculations based on equivalised income for households and based on OECD modified equivalence scale formula.

- Analysis excludes negative and zero income households. These households are included in income quintile calculation.

Source: ANU PolicyMod

Income quintile | 2019–2021 | 2021–2022 | 2019–2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

Quintile 1 | 3.9% | -3.2% | 0.6% |

Quintile 2 | 5.6% | -5.2% | 0.1% |

Quintile 3 | 5.2% | -6.5% | -1.6% |

Quintile 4 | 5.3% | -6.7% | -1.8% |

Quintile 5 | 6.8% | -4.5% | 2.0% |

All households | 5.7% | -5.3% | 0.1% |

Notes

- PolicyMod is based on the ABS Survey of Income and Housing 2017-18 and all dollar variables uprated with latest available data such as average weekly earnings, rental incomes and national accounts data.

- Projections for wages and income support payments set to government budget estimates and projections. Policy changes include those up to 2023 Budget and assumes all measures pass legislation.

- Income quintile calculations based on equivalised income for households and based on OECD modified equivalence scale formula.

- Analysis excludes negative and zero income households. These households are included in income quintile calculation.

Source: ANU PolicyMod

Financial stress

The decline in real wages since 2022 – as indicated by both the WPI and AWOTE – has been driven in part by increases in inflation over this period. As mentioned above, CPI grew by 6.1% in the year to June quarter 2022, reaching a peak of 7.8% over the year to the December 2022 quarter, before returning to 6.0% growth over the year to the June quarter 2023. This compares with an average annual growth rate of 2.4% between December 2001 and 2019.

Biddle and Gray (2023a, 2023b) explored income levels and financial stress over the last 3 years. They found that financial stress (measured by ‘difficult/very difficult to live on present income’) declined from 27% to 17% between February 2020 and November 2020, then increased to 25% by October 2022 (slightly below pre-pandemic levels), continuing to increase to 32% in April 2023. By August 2023, 30% of Australians reported finding it difficult or very difficult to live on their present income (higher than before the pandemic); 10% found it very difficult.

The large decline from February to November 2020 in the proportion of people reporting financial stress is largely due to the introduction of a range of economic support packages (including the Coronavirus Supplement introduced in April 2021 and expanded eligibility for some income support payments), resulting in income increases for low-income households who are more likely to experience financial hardship. Growth in financial stress from October 2021 may have been influenced by the phasing out of these government support packages in 2021. The continued increase in financial stress from October 2022 may reflect the steep increase in inflation in late 2022 that means real household income is declining (Biddle and Gray 2023a; Biddle 2023).

In response to increasing levels of financial stress, the Fair Work Commission granted a 5.75% increase in award wages and an 8.6% increase in the National Minimum Wage to take effect from 1 July 2023. This decision will impact the wages of around one quarter of the Australian employee workforce (Fair Work Commission 2023).

How many people receive income support payments?

Australia’s social security system administered by Services Australia aims to support people who cannot, or cannot fully, support themselves, by providing targeted payments and assistance. Where this is a regular payment that helps with the everyday costs of living it is referred to as an income support payment, with the type of payment often reflecting life circumstances at the time of receipt.

Means-tested arrangements are designed to ensure that income support targets those most in need, by assessing an individual’s income and assets to determine eligibility for a full or part-rate payment (see glossary). People receiving income support are required to report income from all sources (including work, investments and/or substantial assets). Some payments are also subject to activity tests; for example, to remain qualified for JobSeeker, parenting payments or Youth Allowance (Other) recipients are required to actively look and prepare for work in the future. Individuals can receive only one income support payment at a time.

The main income support payments are:

- Age Pension

- Disability Support Pension

- Carer Payment

- parenting payments – Parenting Payment Single and Parenting Payment Partnered

- student payments – Youth Allowance Student and Apprentice, ABSTUDY (Living Allowance), Austudy

- unemployment payments – Newstart Allowance (closed 20 March 2020) and JobSeeker Payment (from 20 March 2020) for people aged from 22 to Age Pension qualifying age (see glossary), and Youth Allowance (other) for people aged 16 to 21. These payments are referred to as unemployment payments on this page (for brevity), noting that some people receiving these payments (those working insufficient hours or exempt from mutual obligations to be looking for work) may not be counted as unemployed (see glossary according to the ABS Labour Force Survey definition (see glossary).

Note, on this page, the proportions of the population receiving Age Pension are presented for those aged 65 and over for consistency with previous reporting and for comparability across the reporting period (2001-2022), despite increases to the qualifying age for Age Pension (see Age Pension for further details).

On this page, ‘income support payments’ are defined as the combination of all these payments, as well as other small payments. These other payments include Special Benefit and some payments that have now ceased but are included in earlier counts:

- Partner Allowance, closed to new entrants September 2003 and ceased January 2022

- Widow Allowance, closed to new entrants July 2018 and ceased January 2022

- Bereavement Allowance, closed to new entrants March 2020 and ceased once bereavement period of all recipients ended

- Sickness Allowance, closed to new entrants in March 2020 and ceased September 2020

- Wife Pension, closed to new entrants in July 1995 and ceased March 2020.

For more information on specific payment types, including payment rates, see Unemployment payments, Parenting payments, Disability Support Pension, Carer Payment and Age Pension. See also Services Australia’s income support payments and the Department of Social Services benefits and payments for more details on government payments.

Recipients aged under 16

A small number of people receiving income support payments were aged under 16 as at 31 March 2023 – 645 for ABSTUDY (Living Allowance), 10 for Youth Allowance (student and apprentice), 5 for Youth Allowance (other), 5 for Carer Payment, 70 for Parenting Payment Single and 800 for Special Benefit. These individuals are included in the numerator in calculating the proportion of people receiving income support payments aged 16 and over in the population, to ensure consistency with income support receipt reported on this page.

COVID-19 response

In late March 2020 to 31 March 2021, short-term policy changes were made to the JobSeeker Payment (such as waiving the assets tests, waiting periods, and mutual obligation requirements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see glossary for definitions of these terms). These changes provide important context as increasing the number of people eligible for the payment is likely to increase the number of people who receive it.

As well as short-term policy changes to the JobSeeker Payment, some new and existing recipients of unemployment payments and other income support payments also temporarily received the Coronavirus Supplement (See Box 4.1 in ‘Chapter 4 The impacts of COVID-19 on employment and income support in Australia’ in Australia’s welfare 2021: data insights for further details). These temporary changes to the JobSeeker Payment and Coronavirus Supplement ended 31 March 2021. Additional economic support packages continue to be available for individuals who work in high-risk settings and have tested positive for COVID-19 (Services Australia 2023).

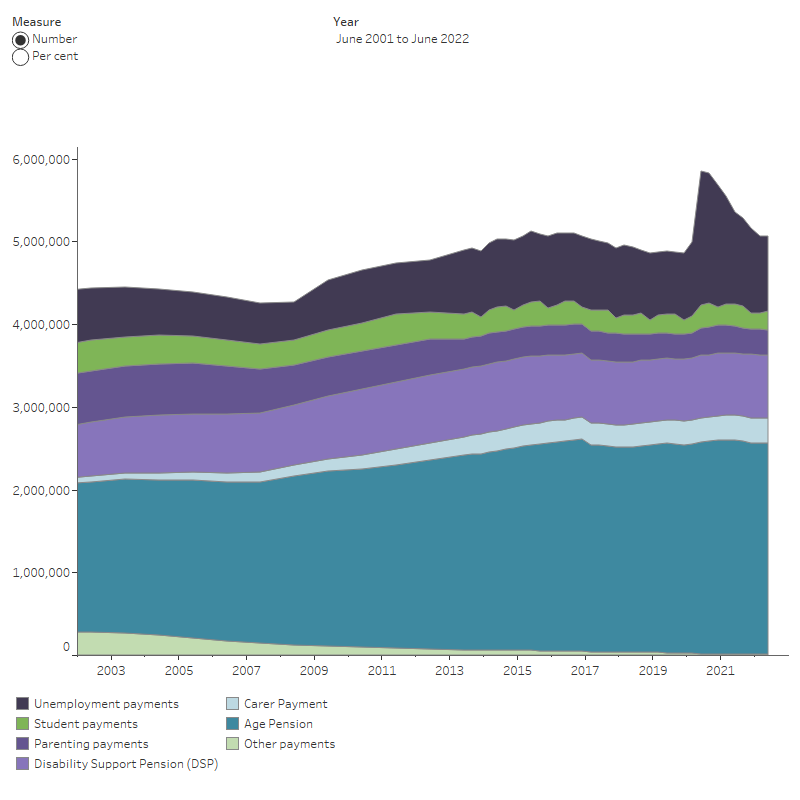

Income support payments

As at 31 March 2023, 5.0 million Australians received income support payments, equating to 24% of the population aged 16 and over. Of these:

- 52% (2.6 million) received Age Pension, or 58% of the population aged 65 and over

- 16% (809,700) received unemployment payments (JobSeeker Payment or Youth Allowance (other)), or 3.8% of the population aged 16 and over

- 16% (769,300) received Disability Support Pension, or 3.7% of the population aged 16 and over

- 6.1% (304,500) received Carer Payment, or 1.4% of the population aged 16 and over

- 5.8% (289,300) received parenting payments, or 1.4% of the population aged 16 and over

- 3.6% (179,600) received student payments, or 0.9% of the population aged 16 and over

- 0.2% (9,200) received other payments, or 0.04% of the population aged 16 and over.

Trends in income support receipt

Before March 2020, the proportion of the population aged 16 and over receiving income support payments had been generally falling, reaching its lowest level in 20 years in June 2019 (24% compared with 28–29% in 2001 to 2005; Figure 2). This reflected, in part, labour market conditions as well as changes to the social security system, such as enhancements to mutual obligation requirements over the last decade (see ‘Chapter 3 Employment and income support following the COVID-19 pandemic’ in Australia’s welfare 2023: data insights for further details).

Reliance on income support increased steeply following the introduction of social distancing and business-related restrictions in early 2020 aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19. There were 861,000 additional people receiving income support between March to June 2020 (a 17% increase in people receiving income support, which equated to an increase from 24% of the population aged 16 and over receiving an income support payment in March to 28% in June).

This steep rise was driven by people receiving unemployment payments, who accounted for 85% of the increase in income support payments over this period. The number of people receiving unemployment payments doubled from 886,200 to 1.6 million (from 4.3% to 7.8% of the population aged 16 and over) between March and June 2020. This reflects the high number of people unemployed or unable to work and increasing eligibility for this payment.

The number of people receiving student payments and parenting payments had more modest increases from March to June 2020 (32% and 12%, respectively), while the number of people receiving disability-related payments remained relatively stable over 2020.

Income support receipt then gradually declined from June 2020 and by June 2022 had returned to pre-pandemic levels and then remained relatively stable to March 2023 (24% of the population aged 16 and over).

For more information on trends on the receipt of particular payment types, see Unemployment payments, Parenting payments, Disability Support Pension, Carer Payment and Age Pension.

Figure 2: Trends in people receiving income support payments, by payment type, June 2001 to June 2022

The line chart shows the number and proportion of people receiving income support by payment type between June 2001 and June 2022. The chart shows that before March 2020, the proportion of the population aged 16 years and over receiving income support payments had been generally falling, reaching its lowest level in 20 years in June 2019. Between March and June 2020, the number and proportion of unemployment payment recipients increased steeply (from 886,200 to 1.6 million, or from 4.3% to 7.8% of the population aged years 16 and over). The number and proportion of unemployment payment recipients then declined to 908,800, or to 4.3% of the population aged 16 and over, by June 2022.

Notes

- Data are as at the end of each corresponding month.

- Data before 2013 may differ from official sources due to differences in methodology.

Per cent refers to the proportion of the population aged 16 and over receiving these payments.

A small number of people receiving income support payments are aged under 16 (1,535 in March 2023). These people are included in the numerator in calculating the proportion of people receiving income support aged 16 and over in the population.

Sources: AIHW analysis of Department of Social Services payment recipient demographic data on data.gov.au (June 2014 – June 2022); unpublished data derived from Services Australia administrative data (June 2001– June 2013).

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on income and income support, see:

- Services Australia A guide to Australian Government payments

- Department of Social Services payment demographic data.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2019) Household Income and Wealth, Australia, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 11 July 2023.

ABS (2020a) Annual wage growth 1.8% in June quarter 2020 [Media Release], ABS, Australian Government, accessed 19 June 2023

ABS (2020b) Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, May 2020, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 5 July 2023.

ABS (2022) Household Income and Wealth, Australia, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 15 February 2023.

ABS (2023a) Australian National Accounts: Distribution of Household Income, Consumption and Wealth, ABS, Australian Government, AIHW analysis of basic microdata, accessed 19 June 2023.

ABS (2023b) Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, ABS, Australian Government, AIHW analysis of basic microdata, accessed 19 June 2023.

ABS (2023c) Average Weekly Earnings, Australia, May 2023, ABS, Australian Government, AIHW analysis of basic microdata, accessed 18 August 2023.

ABS (2023d) Consumer Price Index, Australia, June quarter 2023, ABS, Australian Government, AIHW analysis of basic microdata, accessed 18 August 2023.

ABS (2023e) Wage Price Index, Australia, June 2023, ABS, Australian Government, AIHW analysis of basic microdata, accessed 18 August 2023.

Biddle N (2023) ANU Poll 55 (April 2023): COVID-19, mental health, employment, policy issues, the value of higher education and role of education, science and technology, doi:10.26193/CI4Z2S, Australian National University ADA Dataverse V1, accessed 7 July 2023.

Biddle N and Gray M (2023a) Taking stock: wellbeing and political attitudes in Australia at the start of the post-COVID era, January 2023, ANU Centre for Social Research Methods, accessed 11 May 2023.

Biddle N and Gray M (2023b) Hangovers and hard landings: Financial wellbeing and the impact of the COVID-19 and inflationary crises, August 2023, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, accessed 29 August 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2023) DSS payment demographic data, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 27 March 2023.

Fair Work Commission (2023) Decision: Annual Wage Review 2022-23, Fair Work Commission, Australian Government, accessed 16 June 2023.

Services Australia (2023) A guide to Australian Government paymentsWage Price Index, Australia, June 2023, Australian Government, accessed 24 February 2023.