Welfare expenditure

Citation

AIHW

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Welfare expenditure, AIHW, Australian Government, accessed 27 July 2024.

APA

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Welfare expenditure. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/welfare-expenditure

MLA

Welfare expenditure. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 07 September 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/welfare-expenditure

Vancouver

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Welfare expenditure [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023 [cited 2024 Jul. 27]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/welfare-expenditure

Harvard

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2023, Welfare expenditure, viewed 27 July 2024, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/welfare-expenditure

Get citations as an Endnote file: Endnote

Welfare spending is generally directed toward measures that aim to improve the social and economic wellbeing of the population. It is distinct from health spending in that it focuses on measures such as income support and social and economic employment-related programs and services (for example, unemployment relief and family and relationships services).

See the AIHW's Health expenditure Australia series for more information on health spending.

Both the Australian Government and the state and territory governments contribute to welfare spending, as do non-government organisations and individuals. The Australian Government primarily contributes through cash, which includes family allowances, rent assistance, unemployment benefits and pensions; it also contributes to certain welfare services. The states and territories focus on providing welfare services with less focus on direct payments.

Data on welfare spending that is funded by non-government sources (for example, where a welfare service is funded by donations or fees rather than through government funding) are not readily available in Australia and are not included here.

See Philanthropy and charitable donations for information on non-government donations.

Government welfare expenditure in Australia

In 2021–22, government spending on welfare services and payments was $212.4 billion. The Australian Government funded most of this amount (88% or $186.2 billion), with the remaining 12% funded by state and territory governments.

About welfare expenditure data

Where possible, welfare spending estimates have been developed for consistency with the AIHW's Welfare expenditure Australia series of publications. This ensures trend data are consistent.

Constant prices and ‘real terms’

Spending is reported in constant prices (that is, adjusted for inflation) except where noted. The use of constant price estimates indicates what the equivalent spending would have been had 2021–22 prices applied in all years, as it removes the inflation effect. The phrase ‘real terms’ is also used to describe spending in constant prices. On this page:

- constant price estimates for spending have been derived using deflators produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

- the Consumer Price Index was used as the deflator for cash payments, while the government final consumption expenditure implicit price deflator was used for welfare services.

Comparability with other welfare spending estimates

The Youth Allowance (Students), Austudy and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Study Assistance Scheme (ABSTUDY) are excluded from the welfare spending estimates presented on this page since these programs provide financial assistance for students and apprentices and are considered here as education spending. As a consequence, these estimates are not comparable with figures published elsewhere (such as in the Treasury Final Budget Outcome).

State and territory welfare expenditure

The most recent welfare expenditure data available for state and territory governments are for the 2015–16 financial year, as published in the 2017 Indigenous expenditure report (Productivity Commission 2017), which includes data for both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people and non-Indigenous welfare service expenditure. State and territory data were estimated for 2020–21 to 2021–22 using available trend data from the Indigenous expenditure report and from Government finance statistics (GFS) 2021–22, in which the Classification of the Functions of Government – Australia (COFOG-A) was used (ABS 2015, 2023). In previous reports, the GFS was based on the older Government Purpose Classification (ABS 2005). Hence, the estimated time series data on this page are not fully comparable to previously released data. Any additional spending on welfare services by the states and territories related the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) are also not visible in these data.

Sources of data

Data are sourced from the welfare expenditure dataset of the AIHW, which is, in turn, sourced from publicly available data from:

- the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)

- the departments of Education, Skills and Employment; Health and Aged Care; Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C); Social Services; the Treasury; Veterans’ Affairs

- the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA)

- the Productivity Commission.

Data for 2020–21 and 2021–22 are extracted from the corresponding reports of these organisations (ABS 2023; Department of Education, Skills and Employment 2022, 2023; Department of Health and Aged Care 2022, 2023; Department of the Treasury 2023; Department of Social Services 2022a, 2023; Department of Veterans’ Affairs 2022, 2023; NDIA 2023; PM&C 2022, 2023; Productivity Commission 2023).

Trends in welfare spending

In 2021–22, the Australian and state and territory governments spent $212.4 billion on welfare. In real terms (that is, adjusted for inflation), this was $18.6 billion less than in 2020–21 as many of the pandemic response measures ceased.

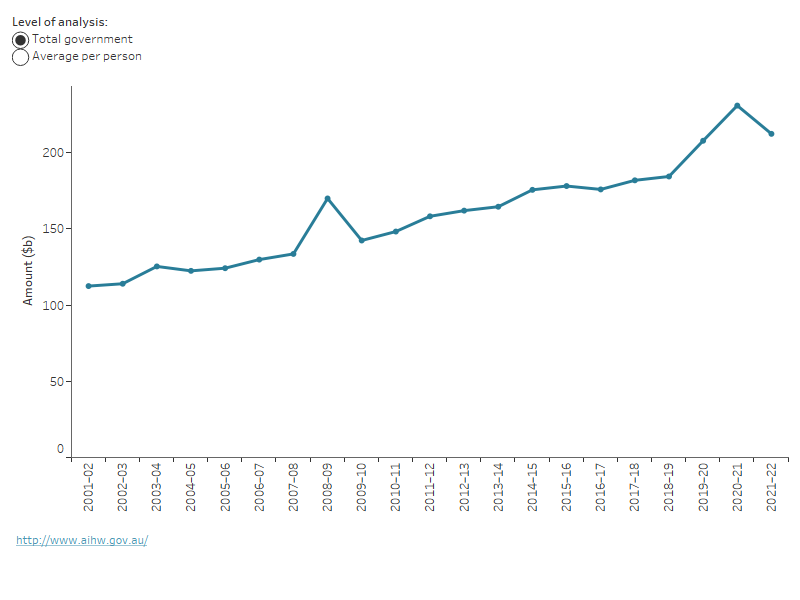

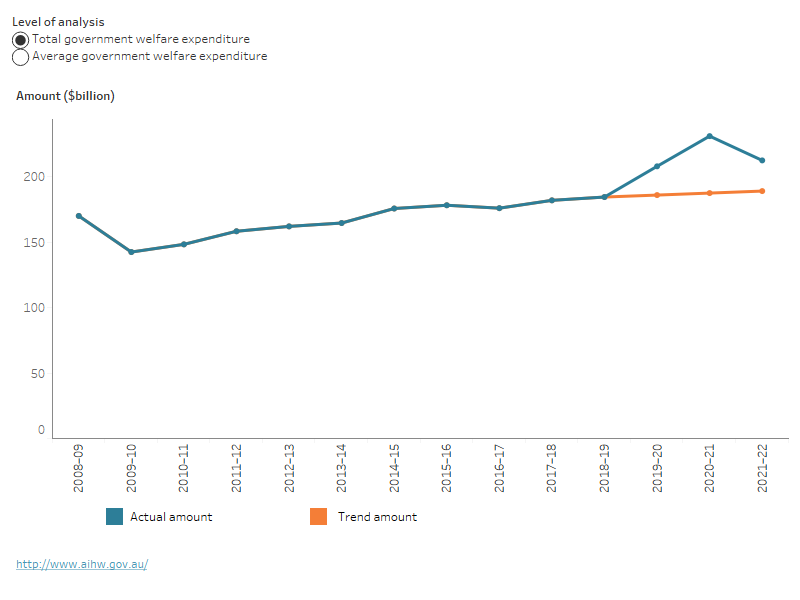

Before 2019–20, welfare spending in Australia had grown with modest rates of 3.4% in 2017–18 and 1.4% in 2018–19, then reached growth rates in 2019–20 and 2020–21 of 12.7% and 11.1% respectively (Figure 1). Total welfare expenditure decreased 8.0% in 2021–22 in real terms. However, the 2021–22 value was still above the long-term trend (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Total government welfare expenditure in Australia, constant prices, 2001–02 to 2021–22

The line chart shows that total government welfare expenditure increased steadily from $112.5 billion in 2001–02 to $212.4 billion in 2021–22. Per person government welfare expenditure increased from $5,804 in 2001–02 to $8,245 in 2021–22. Both the total and per-person government welfare expenditures rose sharply during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008–09 and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note: Constant price estimates are expressed in 2021–22 prices.

Source: AIHW welfare expenditure database.

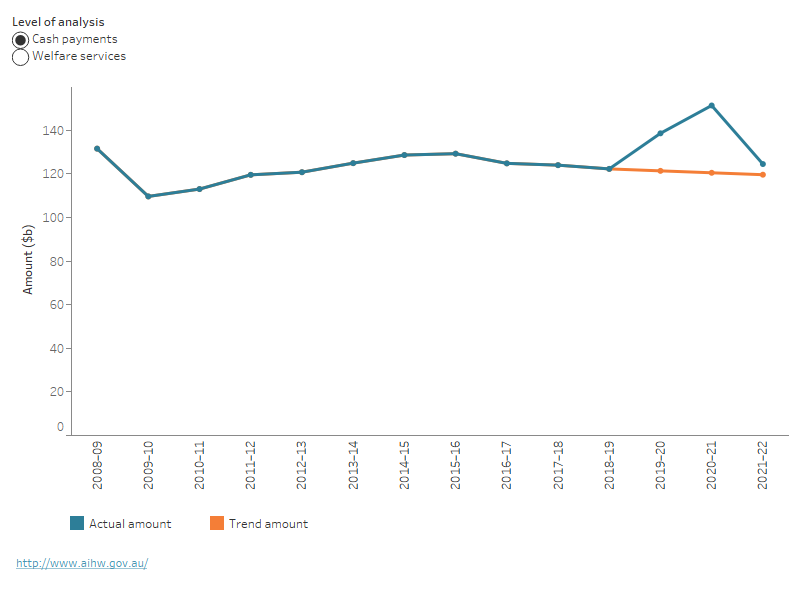

Figure 2: Government welfare spending, constant prices, during the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–20 to 2021–22) compared with the pre-pandemic period

The line chart illustrates that total government welfare spending and per capital government welfare expenditures increased sharply through the period of COVID-19 pandemic (2019–20 to 2020–21) and then decreased considerably in 2021–22. However, despite the decrease in 2021–22, both expenditures have remained above the 10-year trend before the pandemic (from 2008–09 to 2018–19).

Notes:

- Actual amount is the welfare spending in 2021–22 prices.

- Trend amount is the welfare spending in 2021–22 prices, following the trend of the previous 10-year period (assuming the average annual growth rate for the previous 10-year period remains the same for 2019–20 to 2021–22).

Source: AIHW welfare expenditure database.

The main driver of the decrease in welfare spending in 2021–22 was the phasing out of the economic measures that the Australian Government implemented in 2019–20 and 2020–21 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

See Economic response to the Coronavirus (external PDF) .

Before these COVID-19 measures, welfare spending in Australia had grown at a similar pace to population growth, with an upward trend and then real spending per person fluctuating around $7,300 since 2017–18. Then, during the period 2019–20 to 2020–21, real spending per person increased by around 11% per year, as population growth slowed, to achieve $8,146 per person in 2019–20 and $9,010 in 2020–21 (Figure 1). However, this annual welfare spending per capita decreased by 8.5% to $8,245 in 2021–22 in real terms because of the phase out of COVID-19 measures. The government welfare spending per capita in 2021–22 was still higher than the 10-year historical trend before the pandemic (between 2008–09 to 2018–19) (Figure 2).

The welfare spending referred to on this page relates to spending across the entire population and not spending per eligible person in particular programs or per benefit recipient. This more detailed analysis is not included here.

COVID-19 economic response measures

The economic measures mentioned on this page are those which can be related to welfare expenditure data up to the year 2021–22. Note that the COVID-19 Disaster Payment and Pandemic Leave Disaster Payment are outside the scope of this report since these are considered as emergency/crisis payments rather than income support payments. The report does not include the JobKeeper payment since it is wage subsidy for business rather than welfare spending. This page also does not include COVID-19 related spending by other Australian Government agencies, which might fall into a broader scheme Economic response to the Coronavirus (external PDF) .

During 2020–21 and 2021–22, the following economic measures were implemented to support people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Economic support payments

In addition to the one-off economic support payment (ESP) in March 2020, the Government provided 3 ESPs to recipients of social security and veteran payments and family tax benefits, as well as to holders of a pensioner concession card or a Commonwealth senior health card during 2020–21 and 2021–22. Payments of $750 were made in July 2020 and 2 additional ESPs of $250 each from 30 November 2020 and 1 March 2021.

Coronavirus Supplement

From 27 April 2020, eligible income support recipients of the JobSeeker Payment, Parenting Payment, Partner Allowance, Widow Allowance, Youth Allowance (Other) and Special Benefit received the supplement of $550 per fortnight, valid to 24 September 2020. From 25 September 2020, the supplement was reduced to $250 per fortnight, then was $150 per fortnight from 1 January 2021 to 31 March 2021.

The Government made several temporary changes to the JobSeeker Payment which increased the number of recipients. These changes included:

- expanding eligibility to provide access to the payment by sole traders and other self-employed people, permanent employees who have been stood down or who lost their job, and people who are caring for someone affected by COVID-19

- waiving the assets test

- waiving the ordinary waiting period, liquid assets waiting period, newly arrived residents waiting period and the seasonal workers preclusion period

- making the partner income test more generous.

From 1 April 2021, the base rate of the JobSeeker Payment, Parenting Payment, Youth Allowance (Other) and Special Benefit increased by $50 per fortnight, while the income free area that applied to JobSeeker Payment, Parenting Payment (partnered) and Youth Allowance (Other) was increased to $150 per fortnight.

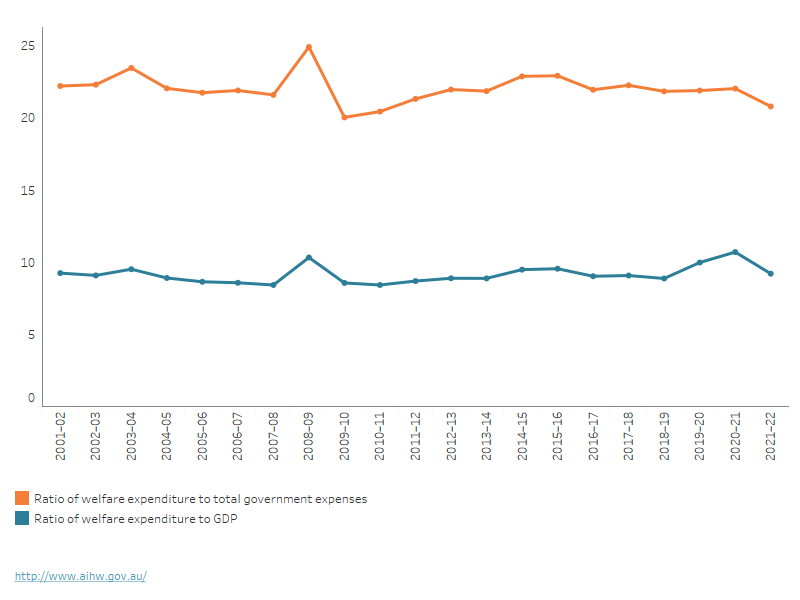

In terms of understanding the proportion of community resources dedicated toward welfare issues, it can be useful to consider a number of comparators over time. In particular:

- Comparing welfare spending to overall economic activity indicates how much of the economy is dedicated to welfare issues.

- Comparing to total government spending indicates how much government resources are being dedicated to welfare issues.

As a proportion of overall economic activity, government welfare spending reduced to 8.4% during the 6 years to 2007–08 before going up to 10.3% in 2008–09 during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). After that, the ratio of welfare spending to gross domestic product (GDP) continued to decrease in the years prior to 2019–20, declining from 9.5% of GDP in 2015–16 to 8.9% in 2018–19. Then, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it grew to 10% and 10.7% of GDP in 2019–20 and 2020–21, respectively. The ratio in 2020–21 was the highest ratio (10.7%) over the last decades up to 2021–22, even higher than that in 2008–09 (10.3%) in the GFC period (Figure 3). However, the ratio of government welfare spending to GDP reduced to 9.2% in 2021–22.

Figure 3: Ratio of government welfare expenditure to government expenses and GDP, 2001–02 to 2021–22

The line graph depicts the trend of welfare spending in relation to total government expenses and GDP for the period 2001–02 to 2021–22. The average ratio of welfare expenditure to the government expenses was 22 percent over the period with a peak during the GFC in 2008–09 and a decline after the COVID-19 pandemic. The government welfare expenditure to GDP ratio was stable though it rose significantly to 10.3% during the financial crisis and 10.7% during the pandemic.

Source: AIHW welfare expenditure database, Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS 2022, 2023).

Other than during the GFC, the proportion of government spending dedicated to welfare has remained relatively stable over the past two decades at around 21–22%. This proportion reached its lowest levels in the years following the GFC, during which there was a sharp increase in government welfare spending.

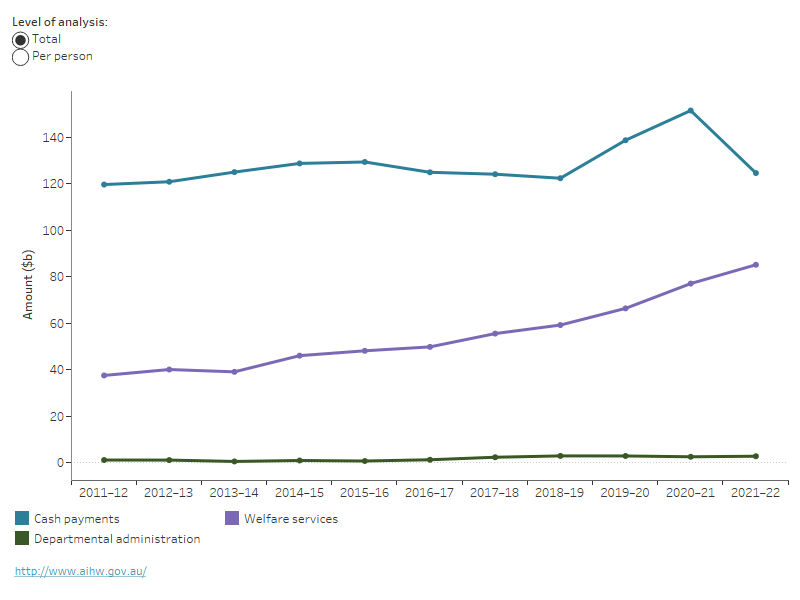

Types of welfare spending

Total amount spent on welfare in 2021–22 was made up of $124.5 billion (59%) in cash payments (see inclusions below), $85.1 billion (40%) in welfare services and $2.8 billion (1%) in departmental administration costs.

The total welfare spending, in real terms, by governments on cash payments had slightly declined in the years before 2019–20, from $129.3 billion in 2015–16 to $122.3 billion in 2018–19, but it increased by 13% in 2019–20 and 9.2% in 2020–21 (Figure 4). However, this spending on cash payments declined significantly by 18% in 2021–22. This significant decrease was mostly due to a number of the Australian Government cash payment programmes for income support ending in 2021–22. See also Income and income support.

Once again it is noteworthy that the cash payments by the Australian Government were still above the 10-year historical trend before the pandemic (2008–09 to 2018–19; Figure 5).

In 2021–22, the estimated $124.5 billion of cash payments by the Australian Government was allocated into these typical welfare programmes:

- Age Pension ($51.1 billion, accounted for 41%)

- Family Tax Benefit ($15.7 billion, 13%)

- Disability Support Payment ($18.3 billion, 15%)

- Carer Allowance/Payment ($9.6 billion, 7.7%)

- JobSeeker Payment ($14.8 billion, 11.9%).

Which cash payments are included?

The cash payments mentioned on this page are those provided by the Australian Government to assist older people, people with disability, people who provide care for others, families with children, war veterans and their families, and people who are unemployed.

The estimates of cash payments present expenditure by the Australian Government, including the programmes such as Age Pension, Family Tax Benefit, Disability Support Pension and Carer Allowance/Payment, and the JobSeeker Payment (previously called Newstart Allowance). The JobKeeper payment from March 2020 to March 2021 is not included in the estimates as it was a wage subsidy for businesses rather than a welfare payment for individuals and households.

To maintain comparability over time, the Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate are included in the estimates of welfare services expenditure (rather than cash payments) since, historically, these payments were paid to the service providers rather than directly to households.

Also, to maintain comparability over time, Youth Allowance (Students), Austudy and ABSTUDY are not included in the estimates on this page, as mentioned earlier.

Figure 4: Government welfare expenditure by types of spending, constant prices, 2011–12 to 2021–22

The line chart shows that cash payments has been larger than welfare services, followed by departmental administration costs over the whole period. Cash payments increased steadily over the period 2011–12 to 2015–16 before decreased in the next three years, then rose sharply in 2019–20 and 2020–21. However, the welfare expenditure by cash payments dropped remarkably in 2021–22. Over the same period, welfare services increased steadily most of the years except a slight decline in 2013–14.

Note: Constant price estimates are expressed in 2021–22 prices.

Source: AIHW welfare expenditure database.

In contrast to cash payments, spending on welfare services has grown steadily over several decades, with the NDIS having a particular impact in recent years on spending on disability services.

In 2021–22, the total amount spent by governments on welfare services was estimated at $85.1 billion, representing a $8.1 billion real increase (10.5%) from 2020–21 (Figure 4). Note that this growth in 2021–22 was above the 10-year historical trend before the pandemic (2008–09 to 2018–19; Figure 5).

Figure 5: Government welfare expenditure by types of spending, constant prices, during the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–20 to 2021–22) compared with the pre-pandemic period

The graph shows a stable increase in the welfare expenditure by government on cash payments from 2009–10 to 2015–16. This was followed by a slight reduction in the next three years before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, during the pandemic period, there was a significant increase in welfare expenditure on cash payments, reaching a peak at $151 billion in 2020–21. It is worth noting that while the government welfare expenditure on cash payments declined considerably in 2021–22, it still remained above the 10-year average trend before the pandemic. On the other hand, the total government expenditure on welfare services increased consistently throughout the entire period with a much greater increase during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic times.

Notes:

- Actual amount is the welfare spending in 2021–22 prices.

- Trend amount is the welfare spending in 2021–22 prices, following the trend of the previous 10-year period (assuming the average annual growth rate for the previous 10-year period remains the same for 2019–20 to 2021–22).

Source: AIHW welfare expenditure database.

The estimates for welfare services spending mentioned on this page include both direct government services and government funding to non-government community service organisations that provide welfare services.

Which welfare services are included?

Welfare services encompass a range of Australian and state and territory government services and programs to support and assist people directly and the community – such as family support services, youth programs, childcare services, services for older people and services for people with disability.

Welfare services expenditure presented on this page is reported for the target groups specified in the COFOG-A (ABS 2015) for the provision of social protection as services provided to individual persons and households, and as services provided on a collective basis:

- welfare services for family and children, for example, youth support services

- welfare services for the aged; for example, home and community care services

- welfare services for people with disability, for example, personal assistance

- welfare services not elsewhere classified (ABS 2015).

Welfare spending as defined according to these 4 target groups does not necessarily include all government spending on services that may have a welfare benefit. For example, some programs relevant to people with disability that might be considered welfare services are in the COFOG-A categories of education, health, or housing. Employment services are not included. Australian Government and state and territory governments funding for welfare services for people with disability under the NDIS are included on this page.

Non-government community service organisations

Both the Australian and state and territory governments indirectly provide welfare services through funding non-government organisations (NGOs) to deliver services. The NGO sector also contributes some welfare services expenditure from its own sources, including fees charged to individuals and through donations.

Government funding to non-government community service organisations (NGCSOs) is included in welfare services expenditure. NGCSO expenditure that comes through fees paid by clients or from the NGCSOs' own sources, such as fundraising, is not included, as comparable data on the sources of these funds are not readily available.

See Philanthropy and charitable donations for information on non-government donations.

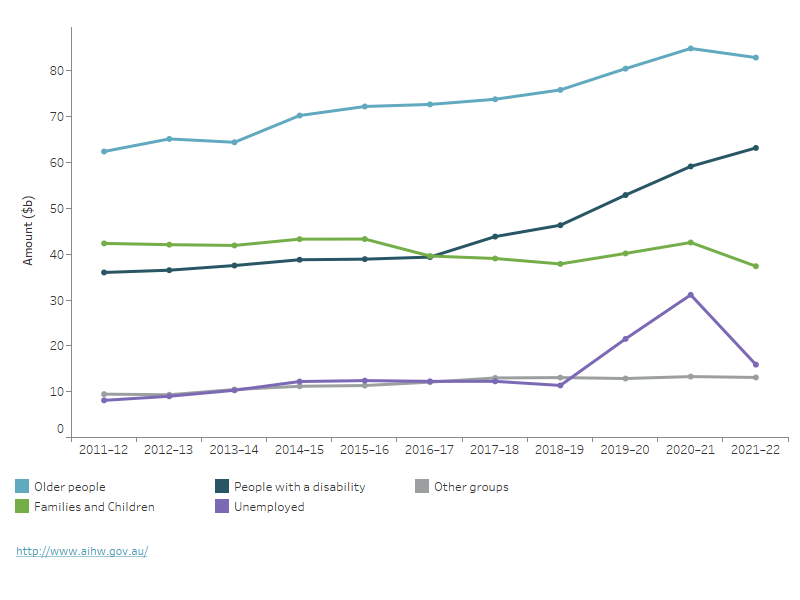

Groups of welfare benefit recipients

In 2021–22, the estimated $212.4 billion of government welfare spending was distributed across these 4 groups of welfare benefit recipients:

- 39% ($82.9 billion) for eligible people aged 65 and over

- 30% ($63.2 billion) for people with disability

- 18% ($37.4 billion) for families and children

- 7.5% ($15.9 billion) for unemployed people (Figure 6).

The remaining 6.2%, or $13.1 billion, was for a range of groups including $2.3 billion in payments specific to First Nations people, and those who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

The 8% decrease in government welfare spending between 2020–21 and 2021–22 can be attributed to declines in spending for:

- unemployed people (decreased by $15.2 billion, largely related to a decrease in unemployment related income support payments caused by fewer number of eligible recipients)

- families and children (decreased by $5.2 billion, largely related to decreases in Family Tax Benefits and Parenting Payments)

- people eligible for the aged pension (decreased by $2.0 billion, largely related to the decline in the number of Age Pension recipients after the increases in the eligibility age on 1 July 2021)

- other groups ($0.2 billion).

For further information see:

Spending on people with disability increased by $4.0 billion between 2020–21 and 2021–22 (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Government welfare expenditure by groups of welfare benefit recipients, constant prices, 2011–12 to 2021–22

The graph indicates government welfare expenditure by targe group over the period of 10 years, from 2011–12 to 2021–22. Over the period, the welfare expenditure for older people has been higher than that for people with a disability, families, and children, followed by unemployed people and other welfare groups. Furthermore, the welfare spending on unemployed people, older people, people with a disability, and families and children increased remarkably in 2019–20 and 2020–21, then decreased in 2021–22, except for people with disability group, which continued to increase in 2021–22. The welfare expenditure on other groups, on the other hand, was relatively stable over the same period.

Note: Constant price estimates are expressed in 2021–22 prices.

Source: AIHW welfare expenditure database.

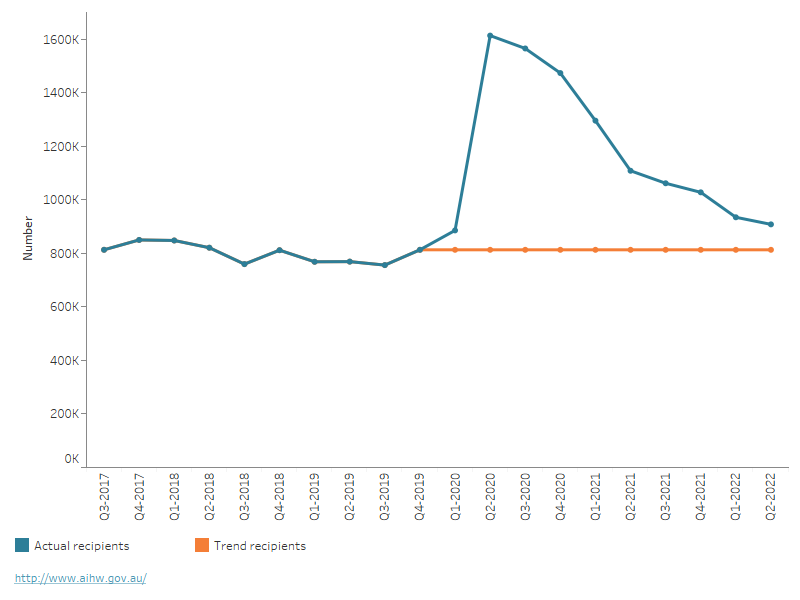

Unemployed people

Total unemployment related income support payments had declined prior to the pandemic, dropping from $12.2 billion in 2017–18 to $11.3 billion in 2018–19. This then increased rapidly to $21.5 billion in 2019–20 and $31.1 billion in 2020–21, as the Australian Government’s COVID-19 economic response measures took effect and there was an increase in the number of eligible recipients of payments (DSS 2022b). This decreased remarkably to $15.9 billion in 2021–22 but was still well above pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 7 shows a large increase in the number of welfare benefit recipients for eligible unemployed people at the commencement of the pandemic, which has been steadily reducing but remains above pre-pandemic numbers (DSS 2022b).

Figure 7: Number of welfare benefit recipients for eligible unemployed persons, quarter 3 2017 to quarter 2 2022, compared with the pre-pandemic period

This line graph shows the number of welfare benefit recipients for eligible unemployed people over the period Quarter 2–2018 to Quarter 2–2022. The number of welfare benefit recipients was relatively stable at around 800,000 until the third quarter in the financial year 2019–20. However, the number of recipients then increased significantly in the second quarter of 2020 to a peak of 1,614,412, following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The number remained high at over 1 million recipients until Dec 2021 and then slowly decreased to around 900,000 recipients at the beginning of the second quarter of 2022. However, even with the decrease, the number of recipients is still well above the previous 10-quarters trend.

Notes:

- Actual recipients are the number of welfare benefit recipients of JobSeeker Payments and Youth Allowance (Other).

- Trend recipients are the number of recipients, following the trend of the previous 10-quarters (assuming the average quarterly growth rate for the previous 10-quarter period remains the same for quarter 4-2019 to quarter 2-2022).

Source: DSS payment demographic (DSS 2022b).

People with a disability

In 2021–22, the total amount spent for people with disability was $63.2 billion – an increase of 6.8% ($4.0 billion) from 2020–21 (in real terms). Between 2018–19 and 2021–22, spending on people with disability increased at an annual average rate of 10.9%, which is higher than the average over the decade since 2011–12 (5.8%). This upward trend appears to be mostly attributed to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) transitioning to the full scheme in all states and territories (except Western Australia) beginning in 2019–20 (DSS 2020). In 2021–22, the NDIS funded about $29.6 billion for people with disability – $19.6 billion by the Australian Government and $10 billion by state and territory governments.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme

The NDIS provides support for Australians with permanent and significant disability, and their families and carers. The Australian and state and territory governments jointly fund the NDIS through intergovernmental agreements.

For more information see Intergovernmental agreements.

Sources and bases of data

- Data for the Australian Government’s contribution to the NDIS for the period 2020–21 and 2021–22 is sourced from Department of Social Services reports.

- Data for state and territory governments over the trial and transition periods of the NDIS were based on the estimates of state and territory data, as described in About welfare expenditure data.

- Data for the full scheme periods are sourced from the NDIS intergovernmental agreements.

- Data for spending outside the NDIS scope are sourced from the Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services (Productivity Commission 2023).

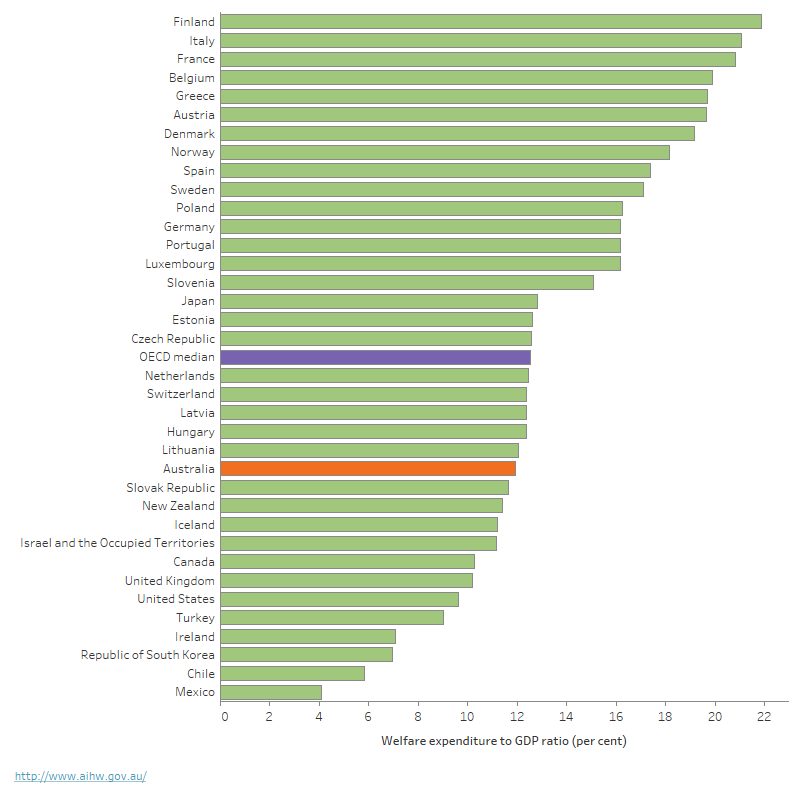

Australia's welfare spending ranking across OECD countries

There are many difficulties in comparing welfare spending across countries. Social support structures in many countries are complex, and not necessarily comparable. Systems generally involve mixtures of:

- government and non-government funding arrangements – including programs funded directly by governments, tax-based systems, employer-focused schemes, and fee-for-service systems

- redistribution models – social support structures in some countries focus on redistribution between sections of the society at particular, but often differing, times. For example, in Australia, unemployment benefits transfer resources via the tax system from the employed to the unemployed. Other schemes act to redistribute resources over the life course (such as through savings and superannuation-based insurance)

- targeted versus non-targeted support arrangements – many countries use means-testing to target support, but do it in different ways, with different thresholds.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data for 2019 (the latest data available) show that welfare expenditure in Australia was 12% of GDP (using the OECD methods for calculating expenditure, which differ from those used for estimates elsewhere on this page). This figure of 12% was slightly lower than the OECD median of 12.5% (Figure 8) and puts Australia ranking 12th out of 36 OECD countries (OECD 2023). Please note that Australia’s welfare spending is generally more targeted with a broadly progressive effect than many other OECD countries.

Figure 8: Welfare expenditure as a proportion of GDP, OECD countries, 2019

The horizontal bar chart shows welfare expenditure as a proportion of GDP across OECD countries in 2019. Finland had the highest proportion of welfare expenditure with 22%, followed by Italy and France (21%). Mexico ranked the lowest with about 4.1%. Australia ranked below the OECD median.

Notes:

- Comparable data are only available for 36 countries (excluding Columbia and Costa Rica) among 38 OECD nations.

- For comparison across OECD countries, health, active labour market and housing programs are excluded from OECD Social expenditure database.

Source: OECD Social expenditure database 2023.

Where do I go for more information?

For more information on welfare expenditure, see:

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2005) Australian system of government finance statistics: concepts, sources and methods, 2005, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 19 February 2023.

ABS (2015) Australian system of government finance statistics: concepts, sources and methods, 2015, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 February 2023.

ABS (2022) Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, September 2022, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 20 May 2023.

ABS (2023) Government Finance Statistics, Annual, 2021–22 financial year, ABS, Australian Government, accessed 24 May 2023.

Department of Health (2022) Health Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2021–22, Department of Health, Australian Government, accessed 18 February 2023.

Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Budget 2022–23: Portfolio Budget Statements, Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

Department of Education (2022) Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2021–22 Education, Skills and Employment Portfolio, Department of Education, Australian Government, accessed 19 February 2023.

Department of Education (2023) Portfolio Budget Statements 2022–23, Department of Education, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

DSS (Department of Social Services) (2020) Department of Social Services Annual Report 2019-20, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 19 January 2023.

DSS (2022a) Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2021-22, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 19 January 2023.

DSS (2022b) DSS Benefit and payment recipient demographic data, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 1 February 2023.

DSS (2023) Portfolio Budget Statements 2022–23, DSS, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

DVA (Department of Veterans’ Affairs) (2022) Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2021–22, DVA, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

DVA (2023) Budget 2022–23 | Department of Veterans' Affairs Budget 2022–23, DVA, Australian Government, accessed 19 May 2023.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2023) OECD.StatExtracts. Social expenditure aggregated data, Paris: OECD, accessed 27 January 2023.

NDIA (National Disability Insurance Agency) (2023) Intergovernmental agreements, NDIA, Australian Government, accessed 12 January 2023.

PM&C (Prime Minister and Cabinet) (2022) Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2021–22, PM&C, Australian Government, accessed 12 January 2023.

PM&C (2023) Portfolio Budget Statements 2022–2023, PM&C, Australian Government, accessed 25 May 2023.

Productivity Commission (2017) Indigenous expenditure report 2017, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 15 January 2023.

Productivity Commission (2023) 15 Services for people with disability - Report on Government Services 2023, Productivity Commission, Australian Government, accessed 13 January 2023.