Chronic conditions and multimorbidity

Chronic conditions are an important global, national and individual health concern. Worldwide, they caused almost 3 in 4 (or 42 million) deaths in 2019 (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network 2020). This proportion has increased over time, from 67% of deaths worldwide in 2010 to 74% in 2019 (Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network 2020). Although 2020 saw a large number of deaths from communicable disease due to the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO 2020), chronic conditions remain an ongoing cause of substantial ill health, disability and premature death.

Chronic conditions generally have long-lasting and persistent effects, and are also referred to as chronic diseases, long-term health conditions or non-communicable diseases. They include conditions such as arthritis, cancer and diabetes. In this report, a ‘chronic condition’ is defined as one of 10 major chronic condition groups: arthritis, asthma, back problems, cancer, selected cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, mental and behavioural conditions and osteoporosis.

The prevalence of these chronic conditions is increasing in Australia. Just under half (47%) of Australians had 1 or more chronic conditions in 2017–18, an increase from 42% of people in 2007–08 (ABS 2018). This is associated with a number of factors, including:

- Australia’s ageing population

- improvements in the treatment and management of chronic conditions which extends life expectancy

- social and behavioural risk factors such as poor diet and physical inactivity (ABS 2018).

As the prevalence of chronic conditions increases, it is expected that multimorbidity – the presence of 2 or more chronic conditions in a person at the same time – will also become more common.

People living with multimorbidity can experience difficulties with everyday activities, poorer overall quality of life and more complex health needs (Fortin et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 2015; Makovski et al. 2019; Marengoni et al. 2011). These outcomes will vary, depending on the number and type of conditions a person has (Fortin et al. 2007; Jackson et al. 2015).

A challenge for health service providers managing multimorbidity is to focus on the person, and all of the conditions they experience, rather than on a single disease (Ording & Sørensen 2013; Starfield 2006).

Multimorbidity can make treatment more complex (Harrison & Siriwardena 2018) and requires ongoing management and coordination of specialised care across multiple parts of the health system (Department of Health 2020a). This places a heavy demand on Australia’s health care system. A key focus of the Australian health system, therefore, is the prevention and better management of chronic conditions to improve health outcomes (Department of Health 2020b). A better understanding of multimorbidity, and of which chronic conditions commonly occur together, can help to inform guidelines for treatment and management.

This work provides baseline information on chronic condition multimorbidity in Australia, before the COVID-19 pandemic. The interaction between pre-existing chronic conditions and COVID-19 infection, as well as any indirect effects on chronic conditions from changes within the health system and wider society due to interventions to manage the spread and impact of COVID-19, may be explored in future work.

Although the term 'chronic conditions' covers a diverse group of conditions, this analysis looks at 10 conditions (Table 1).

| Chronic condition | Inclusions |

|---|---|

| Arthritis |

|

| Asthma |

|

| Back problems |

|

| Cancer |

|

| Selected cardiovascular diseases (heart, stroke and vascular disease) |

|

| Chronic kidney disease |

|

| COPD |

|

| Diabetes |

|

| Mental and behavioural conditions |

|

| Osteoporosis |

|

These conditions were selected because they are common, pose significant health problems and have been the focus of ongoing national surveillance efforts (ABS 2019a). In many instances, action can be taken to prevent these conditions, making them an important focus for preventive health initiatives (Department of Health 2020b). Analysis of these conditions is based on self-reported data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2017–18 National Health Survey (NHS). See NHS chronic condition definitions in the Technical notes for more detail on the collection and definitions of chronic conditions used in this analysis, and Factors to consider when interpreting results.

Almost half of Australians (47%, or more than 11 million people) had 1 or more of the 10 self-reported chronic conditions in 2017–18 (ABS 2018).

Mental and behavioural conditions, back problems and arthritis were the most common of the 10 chronic conditions. It is estimated that about:

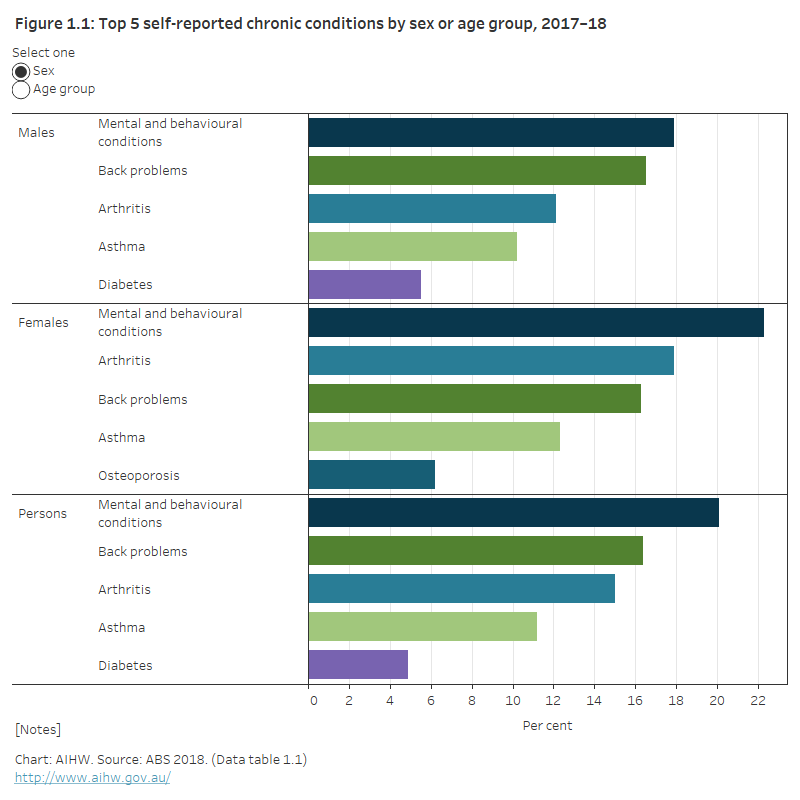

- 4.8 million (20%) people had a mental or behavioural condition, which was the most commonly reported chronic condition for both males and females (Figure 1.1; Data table 1.1)

- 4 million (16%) had back problems, which includes sciatica, disc disorders, and curvature of the spine

- 3.6 million (15%) had arthritis, with females more likely than males (18% compared with 12%) to have arthritis.

In 2017–18, the most common condition(s) for people aged:

- 15–44 were mental and behavioural conditions (22%)

- 45–64 were back problems and arthritis (25% each)

- 65 and over was arthritis (49%) (ABS 2018).

Four in 5 Australians aged 65 and over (80%) were estimated to have 1 or more of the selected chronic conditions in 2017–18 (ABS 2018).

For further detail on some of the most common conditions see Chronic disease.

Figure 1.1: Top 5 self-reported chronic conditions by sex or age group, 2017–18

The figure shows the most common self-reported chronic conditions by either sex or age group in 2017–18. The most common chronic conditions for people of all ages were mental and behavioural conditions (20%), back problems (16%), arthritis (15%), asthma (11%) and diabetes (4.9%).

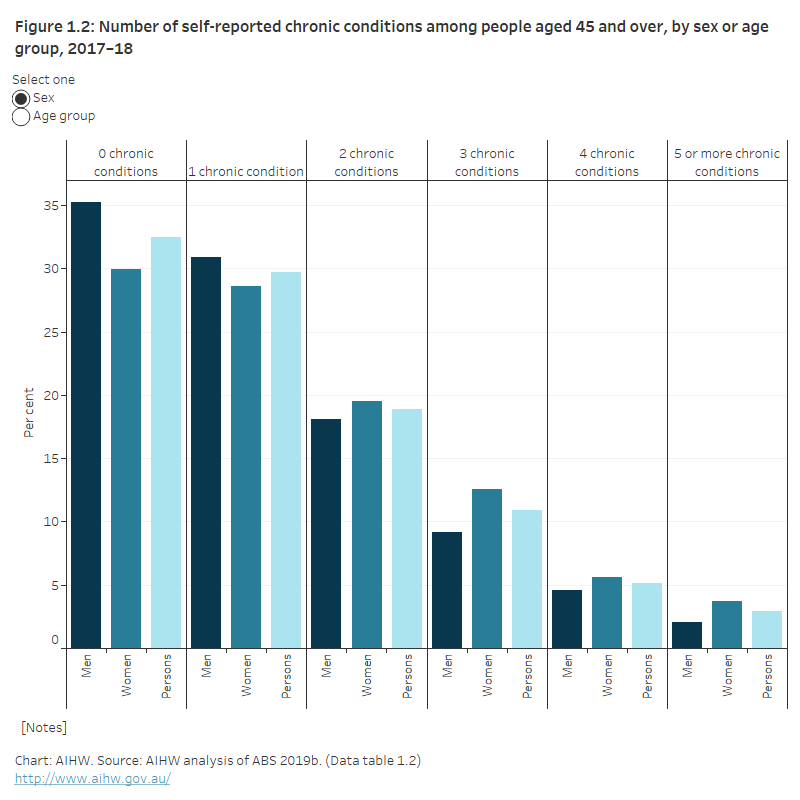

Nearly 3 in 4 (74%) people with 2 or more of the selected chronic conditions were aged 45 and over. Of those aged 45 and over, 38% had 2 or more chronic conditions and 2.9% had 5 or more (Figure 1.2; Data table 1.2). Females were less likely to have no chronic conditions (30%) than males (35%).

The proportion of people with no chronic conditions decreased with age. Just over half of those aged 45–49 (51%) had no chronic conditions compared with 17% of those aged 75 and over. In contrast, the proportion of people with 3, 4 and 5 or more chronic conditions generally increases with each 5–year age group from 45–49 years to 75 years and over.

Figure 1.2: Number of self-reported chronic conditions among people aged 45 and over, by sex or age group, 2017–18

The figure shows the proportion of people aged 45 and over with 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 or more self-reported chronic conditions, by either sex or age group. Women were more likely to have 5 or more chronic conditions (3.7%) compared with men (2.0%). The proportion of people with 5 or more conditions increased with age; 5.5% of people aged 75 and over had 5 or more conditions.

What is the impact of chronic conditions?

Living with chronic conditions can substantially influence a person’s health and their health service use. Analysis of the National Hospital Morbidity Database, National Mortality Database and Australian Burden of Disease Study 2015 data shows the 10 selected chronic conditions:

- were involved in 5 in 10 hospitalisations (51%) in 2017–18 where at least 1 of the selected conditions was recorded as either the principal or additional diagnosis in the hospitalisation (Box 1).

- contributed to nearly 9 in 10 deaths (89%) in 2018 where at least 1 of the selected conditions was recorded as either the underlying or associated cause of death. The result did not change when data was adjusted for Victorian additional death registrations for 2018 that were recorded in 2019 (ABS 2020).

- contributed to about two-thirds (66%) of the total burden of disease (fatal and non-fatal) in Australia in 2015 (excluding burden associated with osteoporosis which is not available within current burden of disease estimates) (AIHW 2019). See Burden of disease for more information on definitions and the burden of disease associated with these conditions.

Box 1: Key terms

additional diagnosis: The diagnosis of a condition or recording of a complaint – either coexisting with the principal diagnosis or arising during the episode of admitted patient care (hospitalisation), episode of residential care or attendance at a health care establishment – that requires the provision of care. Multiple diagnoses may be recorded.

associated cause(s) of death: A cause(s) listed on the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death, other than the underlying cause of death. They include the immediate cause, any intervening causes, and conditions that contributed to the death but were not related to the disease or condition causing death.

burden of disease (and injury): Term referring to the quantified impact of a disease or injury on a population, using the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) measure.

disability-adjusted life years (DALY): A measure of healthy life lost, either through premature death or living with disability due to illness or injury. Often used synonymously with health loss.

fatal burden: The burden from dying ‘prematurely’ as measured by years of life lost. Also referred to as ‘life lost’.

non-fatal burden: The burden from living with ill-health as measured by years lived with disability.

principal diagnosis: The diagnosis established after study to be chiefly responsible for occasioning an episode of patient care (hospitalisation), an episode of residential care or an attendance at the health care establishment. Diagnoses are recorded using the relevant edition of the International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM).

underlying cause of death: The disease or injury that initiated the train of events leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence that produced the fatal injury.

Estimates of the number of Australians affected by 1 or more of the 10 selected chronic conditions come from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2017–18 National Health Survey (NHS). The 2017–18 NHS was completed by approximately 21,300 Australians from 16,400 private dwellings (ABS 2018).

Data on the presence and consequences of chronic conditions are based on self-reported data. This analysis is largely based on analysis of NHS data as these data enable us to look at the co-occurrence of the selected chronic conditions across the Australian population to produce estimates of multimorbidity.

Prevalence estimates are based on information ‘as reported’ by NHS respondents and may differ from those reported elsewhere due to differences in the data source used, including differences in the method of data collection (for example, self-report survey compared with diagnostic survey), as well as the specific chronic conditions included in analysis and how they are defined. In particular, estimates of people with self-reported mental or behavioural conditions in this analysis will differ from those obtained from a diagnostic tool such as that used in the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. The questions asked of NHS respondents are available in the National Health Survey questionnaire, 2017–18.

The NHS does not include the experiences of older people in institutionalised dwellings (such as residential care facilities). This may mean the prevalence of chronic conditions and multimorbidity is underestimated.

Estimates of multimorbidity and complex multimorbidity types in this analysis represent multimorbidity associated with the 10 selected chronic conditions only, and may not reflect the prevalence of multimorbidity more broadly.

For further detail, see Factors to consider when interpreting results in the Technical notes.

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. National Health Survey: First Results, 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2019a. National Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2017–18. ABS cat. no. 4363.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

ABS 2019b. Microdata: National Health Survey, 2017–18. DataLab. ABS cat. no. 4324.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS. Findings based on Detailed Microdata.

ABS 2020. Causes of death, Australia methodology. ABS cat. no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2015—Summary. Cat. no. BOD 21. Canberra: AIHW.

Department of Health 2020a. Health Care Homes. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 18 November 2020.

Department of Health 2020b. National Preventive Health Strategy. Canberra: Department of Health. Viewed 18 November 2020.

Fortin M, Dubois MF, Hudon C, Soubhi H & Almirall J 2007. Multimorbidity and quality of life: a closer look. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 5(52).

Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C & Vanasse A 2005. Multimorbidity is common to family practice. Is it commonly researched? Canadian Family Physician 51(2):244–245.

Harrison C, Britt H, Miller G & Henderson J 2014. Examining different measures of multimorbidity, using a large prospective cross-sectional study in Australian general practice. BMJ Open 4(7): e004694.

Harrison C & Siriwardena AN 2018. Multimorbidity: editorial. Australian Journal of General Practice 47(1–2).

Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network 2020. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Seattle, United States: IHME. Viewed 15 December 2020.

Jackson CA, Jones M, Tooth L, Mishra GD, Byles J & Dobson A 2015. Multimorbidity patterns are differentially associated with functional ability and decline in a longitudinal cohort of older women. Age and Ageing 44(5):810–816.

Jakovljević M & Ostojić L 2013. Comorbidity and multimorbidity in medicine today: challenges and opportunities for bringing separated branches of medicine closer to each other. Medicina Academica Mostariensia 1(1):18–28.

Makovski TT, Schmitz S, Zeegers MP, Stranges S & van den Akker M 2019. Multimorbidity and quality of life: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews 53.

Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A et al. 2011. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Research Reviews 10:430–9.

Ording AG & Sørensen HT 2013. Concepts of comorbidities, multiple morbidities, complications, and their clinical epidemiologic analogs. Clinical Epidemiology 5:199–203.

Starfield B 2006. Threads and yarns: weaving the tapestry of comorbidity. Annals of Family Medicine 4(2):101–103.

Valderas J, Sarfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C & Roland M 2009. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. Annals of Family Medicine 7:357–363.

WHO (World Health Organisation) 2020. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 15 December 2020.